Frances Cranmer Greenman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Frances Willard Cranmer June 28, 1890 |

| Died | May 24, 1981 (aged 90) |

| Resting place | Lakewood Cemetery |

| Style | Painting |

| Movement | Modernism |

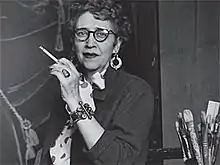

Frances Cranmer Greenman (June 28, 1890 – May 24, 1981) was an American portrait painter, critic and columnist.

Early life and education

Frances Willard Cranmer was born on June 28, 1890, in a log cabin in Aberdeen, South Dakota. Her parents were Hon. Simeon Harris Cranmer, and the suffragist, Emma Amelia Cranmer.[1] She was named for suffragist Frances Willard. At 15, she attended the Wisconsin Academy of Art.[2] At 16, she attended the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. In the 1900s, she studied with William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri in New York City. She won a gold medal from Corcoran in 1908.

Career

She moved to Minneapolis in the 1910s. She had her first major exhibition in 1913 at the Handicraft Guild.[3] She went back to New York for several years before settling at the Hampshire Arms Hotel. Her permanent studio was on the fifth floor of the building and was painted completely black for her portraiture.[4]

She was awarded a gold medal at the 1915 Minnesota State Fair for a group of three portraits.[5]

Greenman was an established society painter in Minneapolis by the early 1920s and made portraits for Hollywood stars, politicians and socialites.

Her 1921 exhibition at the Bradstreet Gallery in Minneapolis was described in American Art News as "alternately gay and serious, prismatic and tonal."[6] Greenman was awarded first prize in painting at the seventh and eighth annual exhibitions of Twin City Artists. Her portrait Jane won the prize for the eighth exhibition in 1922.[7]

Greenman was replaced as a judge during the 1925 Iowa State Fair's Art Salon due to her modernist inclinations. Painter and exhibit head Charles Atherton Cumming postponed the art judging, first claiming that Greenman was ill. Greenman herself disputed this and Cumming went on to describe how she had been "converted to what she calls 'modern' art since I last viewed her exhibit." He explained that Iowa artists were "followers of 'white man's art'" and Greenman was replaced by one J. Laurie Wallace.[8][9]

Following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Greenman left New York and supported her family by painting portraits for wealthy clients.[10]

Greenman taught at the Minneapolis School of Art from 1941 to 1943. She also taught at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Her style was bold and informed by modernism.[4] Her painting Pink Lotus depicted one David Painter and in a severe, flattened, and unflattering manner. While her earlier portraits were more adventurous, they became more conservative and conventional over time. Her 1922 work A Moment's Rest for Mrs. Hoscovics and her portraits of Polish immigrants in Wisconsin show that Greenman wanted to use her art to explore social issues.[10]

Greenman painted portraits of many famous people, including conductor Emil Oberhoffer, Dolores del Río, and Mary Pickford. She painted the official governor's portrait of Karl Rolvaag. It is hung in the Minnesota State Capitol.[11]

She wrote her autobiography, Higher Than the Sky in 1954. She also worked for the Minneapolis Sunday Tribune as a critic, writing the art column "Frances Greenman Says".

Death

Greenman died in Medina, Minnesota, on May 24, 1981.[2]

References

- ↑ Willard, Frances Elizabeth; Livermore, Mary Ashton Rice (1893). A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life (Public domain ed.). Moulton. pp. 214–.

- 1 2 "Profiles of the five women artists". MPR News. July 18, 2007. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Crump, Robert L. (2009). Minnesota Prints and Printmakers, 1900-1945. Saint Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-87351-635-8.

- 1 2 Sturdevant, Andy (January 14, 2015). "Frances Cranmer Greenman: Her art and autobiography depict 20th-century Minneapolis". MinnPost. Archived from the original on October 29, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ M. J. (November 1915). "Art and Agriculture in Minnesota". Art and Progress. 7 (1): 36. JSTOR 20561584.

- ↑ "Minneapolis". American Art News. 19 (27): 9. April 16, 1921. JSTOR 25589802.

- ↑ "Minneapolis". American Art News. 21 (1): 10. October 14, 1922. JSTOR 25590008.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Chris (2015). Carnival in the Countryside: The History of the Iowa State Fair. University of Iowa Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-60938-357-2.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Chris (Spring 1995). "Agricultural Lag: The Iowa State Fair Art Salon, 1854-1941". American Studies. 36 (1): 15. JSTOR 40643728.

- 1 2 Owens, Gwendolyn (2005). American Women Modernists: The Legacy of Robert Henri, 1910-1945. Provo: Rutgers University Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 0-8135-3684-7.

- ↑ Thornley, Stew (2004). Six Feet Under: A Graveyard Guide to Minnesota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-87351-514-5.

Further reading

- Frances Cranmer Greenman papers, 1925-1957, Archives of American Art.

- Pioneer Modernists: Minnesota's First Generation of Women Artists by Julie L'Enfant