| Fort Andrews | |

|---|---|

| Part of Harbor Defenses of Boston | |

| Peddock's Island, Massachusetts | |

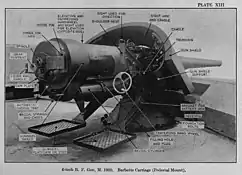

At the height of its armament, the fort had 16 M1896 mortars as shown, in 4 pits of four mortars each. In 1910 four of these were sent to the Philippines; these were replaced by four M1908 mortars. Later 6 mortars (2 from each of 3 pits) were removed. This photo most likely depicts Pit A of Battery Cushing at Fort Andrews. | |

Fort Andrews Location in Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates | 42°18′06″N 70°55′53″W / 42.30167°N 70.93139°W |

| Type | Coastal Defense, later POW camp |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area |

| Open to the public | yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1898-1904 |

| Built by | United States Army |

| In use | 1901-1947 |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

Fort Andrews was created in 1897 as part of the Coast (later Harbor) Defenses of Boston, Massachusetts.[1] Construction began in 1898 and the fort was substantially complete by 1904.[2] The fort was named after Major General George Leonard Andrews, an engineer and Civil War commander, who assisted in the construction of nearby Fort Warren in Boston Harbor. It occupies the entire northeast end of Peddocks Island in Boston Harbor, and was originally called the Peddocks Island Military Reservation. Once an active Coast Artillery post, it was manned by hundreds of soldiers and bristled with mortars and guns that controlled the southern approaches to Boston and Quincy Bay. The fort also served as a prisoner-of-war camp for Italian prisoners during World War II, who were employed as laborers following the Italian surrender to the Allies in 1943.[2] Today, the fort is abandoned, and is managed by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, as part of the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area.

Armament

Fort Andrews' gun and mortar batteries as built were as follows:[2][3]

| Name | No. of guns | Gun type | Carriage type | Years active |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cushing | 8 | 12-inch coast defense mortar M1890 | barbette M1896 | 1904-1942 |

| Whitman | 8 | 12-inch coast defense mortar M1890 | barbette M1896 | 1902-1942 |

| McCook | 2 | 6-inch gun M1900 | pedestal M1900 | 1904-1947 |

| Rice | 2 | 5-inch gun M1900 | pedestal M1903 | 1909-1917 |

| Bumpus | 2 | 3-inch gun M1902 | pedestal M1902 | 1905-1946 |

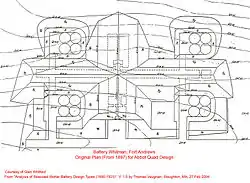

In its heyday, the fort's armament was impressive. Fort Andrews was the site of one of Boston Harbor's two 12-inch coast defense mortar complexes (the other was Fort Banks), meant to protect the southern approaches to Boston Harbor. The two pits of Battery Whitman at the northwest end of the fort were initially planned to be the first two pits of a four-pit (16-mortar) battery, in a so-called Abbott Quad design.[4] With a range of 7 miles, these batteries could reach both the northern and southern channels into the harbor, interlocking with the fire of Fort Banks' mortars.

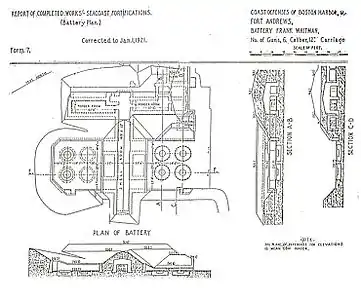

As it was, only two pits (in a north-south alignment) were built for Battery Whitman (Whitman Pit A is the southerly one, with Pit B behind it), and two more, of a slightly different design, became Battery Cushing (built just to the east and in an east-west alignment). When fully equipped, these pits contained 16 12-inch coast defense mortars, able to bombard the southern approaches to the harbor with projectiles weighing over 1,000 pounds (450 kg) each. Three of the mortar pits are still visible. The fourth (the most easterly of Cushing's two pits — Pit A) has been partially filled with debris from the recent demolition of other structures at the fort.[5]

The Boston press reported that when the mortars were test-fired in the 1920, they literally blew doors off of nearby barracks buildings and broke windows at the fort. Island residents also told of the blast from the mortar barrels igniting brush fires on the grassy slopes of the mortar pits.

In addition, the fort had two 6-inch guns of Battery McCook (and until 1917 two 5-inch guns of Battery Rice) and two 3-inch guns of Battery Bumpus in concrete emplacements at the top of the bluff northeast of the fort,[2] overlooking Nantasket Roads (the main channel to Quincy Bay), the shipyards beyond, and (formerly) the southern entrance to Boston Harbor itself.[6] The gun emplacements can still be seen, but they are seriously deteriorated and somewhat dangerous to visit.

History

Fort Andrews was constructed in 1898-1904, one of many forts of the Endicott program, including an initial seven forts in the Boston area.[7][3] Fort Andrews was one of two Endicott period forts of this size in Boston Harbor,[8] the other being Fort Strong, on Long Island, and after the demolition of almost all of Fort Strong's wooden structures in about 2005 to make way for a children's camp, Fort Andrews is the sole survivor of its type in Massachusetts.

In 1910 the four M1890 mortars of Battery Whitman, Pit A, were removed to provide half the armament for Battery Geary at Fort Mills on Corregidor Island in the Philippines. In 1913 Pit A was rearmed with four M1908 mortars.[2]

World War I brought further changes to Fort Andrews' armament. In February 1917 Battery Rice's two 5-inch guns were transferred to Fort Story at Cape Henry, Virginia for an emergency battery. The 5-inch gun was withdrawn from Coast Artillery service shortly after the war, and these guns were never replaced. In August 1917, Battery McCook's two 6-inch guns were ordered dismounted for potential service on field carriages on the Western Front. It appears these guns never left the fort, and they were remounted in 1920.[2] As part of a forcewide re-alignment, almost half of Fort Andrews' mortars were removed in early 1918. It was determined that attempting to simultaneously reload four mortars per pit was inefficient, and that a similar rate of fire could be obtained with only two mortars per pit. Also, many 12-inch mortars were needed as railway artillery for potential service on the Western Front. None of these mortars were shipped to France before the Armistice, but many were retained as railway mortars through World War II. The result at Fort Andrews was that Battery Cushing was reduced to four mortars and Battery Whitman was reduced to six mortars. For some reason, Pit A of Battery Whitman retained its four M1908 mortars.[2] By the 1920s, Fort Andrews consisted of some 30 structures (see map at left), ranging from large brick barracks buildings that housed over 100 soldiers each to elegant officers' quarters and a 50-bed hospital. The fort even had a radio transmitting station, one of the Army's earliest.

After World War I, Fort Andrews was put on caretaker status ("mothballed"), and was brought back into action again during World War II. By the 1930s the fort's mortars were superseded by the long-range guns of Fort Ruckman and Fort Duvall. In 1942 the fort's massive coast defense mortars were scrapped, but its 6-inch and 3-inch guns served out the war guarding the southern approaches to Boston Harbor. The fort also served as a prisoner-of-war camp for Italian prisoners during World War II, who were employed as laborers following the Italian surrender to the Allies in 1943.[2]

In 1946, Ft. Andrews was decommissioned by the Army, and in the 1970s it was purchased, along with the rest of Peddocks Island, by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.[9]

In 2010, most of the fort's structures were seriously dilapidated or in danger of collapse, and Peddocks Island, normally reachable by ferry from Hull, was temporarily closed to the public. The island was reopened on 8 July 2011.

Fire Control Structures

Ft. Andrews is unusual in the number of different types of fire control structures it has. These were to house the evolving Coast Artillery fire control system. These were constructed beginning in 1904, with new structures built through World War II.

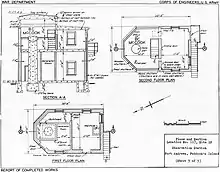

The oldest fire control structure at the fort is the so-called East Side fire control building, completed in 1904. Its position (42°18′04″N 70°55′42″W / 42.301185°N 70.928462°W), 100 ft. high on the hill to the northeast of the parade ground, gave it a commanding view of the southern harbor channels and out to sea.[10] This structure originally contained a vertical base end station for Battery McCook, as well as observation instruments for the Commander of the fort and a plotting room.

A second east side fire control station was the coincidence range finder (CRF) station that was located (42°18′06″N 70°55′46″W / 42.301715°N 70.929545°W)in a blockhouse constructed in 1925 on the gun platform for Gun #1 of Battery Rice, a 5-inch battery built in the early 20th century but for which the guns were never delivered. This small (13-foot square) structure housed a Barr and Stroud CRF device that, with a length of 9 ft., must have made for very cramped quarters.

The third fire control station on the east side, also built in 1925, was the small pillbox that housed a second depression position finder (DPF) for Battery McCook. The position of this emplacement (42°18′09″N 70°55′48″W / 42.302381°N 70.930062°W), about 350 ft. northwest of the battery, near the lip of the tall northern bluffs of the island, gave it a commanding view over toward Ft. Warren on Georges Island and the surrounding channels into Boston.[11]

This was the original "Abbot Quad" plan for Battery Whitman. |

This later plan for Battery Whitman enlarged the pits and kept only half of the original battery. |

The East Side fire control station. |

World War II-era Elevation and plans for the 1904 East Side station. |

Bty Bumpus CRF station (1925). |

Bty McCook DPF Pillbox (1925). |

1944 Base End Station |

South End of Collapsed 1907 West Side Building. |

Atop the tall hill on the west side of the parade ground were two more stations. In 1944, a single-story concrete bunker was built to house base end station #1 for Battery McCook. Located at a height of 128 feet above sea level (42°17′56″N 70°55′54″W / 42.298989°N 70.931764°W), this structure housed a depression position finder (DPF). Today, the structure is thickly overgrown with trees and brush, but during World War II controlled burns kept the brow of the hill clear of obstructions.

The final fire control structure is a two-bay wood and plaster building that was 40 ft. long overall, constructed in 1907, and had dual observation platforms and plotting rooms for mortar batteries Whitman and Cushing, northwest of the parade ground. Located (42°17′57″N 70°55′55″W / 42.299118°N 70.931906°W) about 80 ft. northwest of the 1944 bunker described above, this building has now collapsed under the weight of fallen trees, and its remaining walls are shaky. The building was built in a 15 ft. deep pit, with only its observation windows likely projecting above ground level, and today (in 2010) this renders it almost invisible until a visitor is virtually on the edge of the pit. The ruins are significant for being the only remains of one of the early wood and plaster fire control buildings that were so prevalent throughout Boston's harbor defenses in the period 1905-1925.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Construction dates and structure or battery details used in this article come from period documents such as Quartermaster's records and Army Engineers Reports of Completed Works (RCWs), as reproduced from National Archives originals and distributed on DVD by the Coast Defense Study Group, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fort Andrews at FortWiki.com

- 1 2 Berhow, p. 206

- ↑ This was also the design that was used to build Boston's other two mortar batteries, at Fort Banks in Winthrop, MA. For a discussion of the Abbott Quad and an inventory and discussion of all U.S. coast defense mortar batteries, see Analysis of Seacoast Mortar Battery Design Types (1890-1925), by Thomas Vaughan, Version 1.0. Stoughton, MA, 27 February 2004.

- ↑ On the map above, the four mortar pits are indicated by small rectangles, each with four dots(indicating the planned number of mortars) within it.

- ↑ Before the causeway to Long Island was constructed, ships could pass between Moon Island and Deer Island. These passages were protected by anti-ship and anti-submarine booms during World War II.

- ↑ Harbor Defenses of Boston at NorthAmericanForts.com

- ↑ Fort Warren, on Georges Island, also covered a large area, but most of its structures were obsolete, dating from the pre-Civil War era.

- ↑ A few retired non-commissioned Army officers were permitted to continue to occupy quarters at the fort late into the last century, but today there is only one year-round resident on the island.

- ↑ Today, this building is surrounded by 50-foot-tall (15 m) trees and heavy brush. Up through WW2, it was totally exposed on a bare ridge line.

- ↑ The remains of a 1920s era coastal searchlight emplacement can be found about 40 ft. southwest of this pillbox. The searchlight was of the type that could be lowered into a concrete pit when not in use. Both this pit and the access hatch of the pillbox are now open and heavily overgrown, making them dangerous for an unwary visitor.

Bibliography

- Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide (Third ed.). McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- Butler, Gerald (2000). The Military History of Boston's Harbor Islands. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0738504645. OCLC 45751673.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Silvia, Matilda (2003). Once Upon an Island. Hot House Press. ISBN 0970047657. OCLC 52108654.

External links

- CoastDefense.com, a website on Fort Andrews and coast defense in New England, with extensive photo galleries.

- Harbor Defenses of Boston at NorthAmericanForts.com