Folk Orthodoxy (Russian: народное православие; Bulgarian: народно православие; Serbian: народно православље; Latvian: narodno pravoslavlje) refers to the folk religion and syncretic elements present in the Eastern Orthodox communities.[1] It is a subgroup of folk Christianity, similar to Folk Catholicism. Peasants incorporated many pre-Christian (pagan) beliefs and observances, including the coordination of feast days with agricultural life.

Overview

Folk Orthodoxy has developed an interpretation of rituals, sacred texts, and characters from the Bible. Religious syncretism coexists with Christian doctrine and elements of pre-Christian pagan beliefs.[2] According to historian and ethnologist Sergei Anatolievich Shtyrkov, the boundary between canonical and folk Orthodoxy is not clear or constant and is drawn by religious institutions such as the Russian Orthodox Church (which often evaluate the latter as superstition or paganism).[3]

Dual faith

The term Dvoeverie ("dual faith") appeared during the Middle Ages, used in sermons directed against Christians who did not stop worshipping pagan deities. It indicates the conflict between two religious systems: paganism and Christianity. The term religious syncretism, on the other hand, implies a merge.[4][5][6]

The concept of "dual faith" originated in the Christian Church; in early Christianity, non-canonical religious practices by Christians were denounced. In the fourth-century Eastern Roman Empire, Asterius of Amasia (c. 350 – c. 410) opposed the celebration of calends in his sermons. Basil the Great (c. 350 – c. 410) denounced his Christian contemporaries for gravesite commemoration, which took on characteristics of pagan Lupercalia. In the Western Roman Empire, the Church Fathers also denounced some Christians for the remnants of pagan customs in their lives.

The concept of dual faith is inherent in all Christian cultures. All Souls' Day and its eve, Halloween are an example. Halloween is an ancient Celtic pagan holiday[7] commemorating ancestors, similar to All Saints' Day.[8][9] A number of Christian cultures celebrate Carnival before Great Lent, which preserves pre-Christian customs.[10]

In Russia, this concept appears with the church's opposition to paganism. According to "The word of a certain Christ-lover and zealot for the right faith",

... So also this so called "Christian" could not tolerate Christians who double-mindedly live, who believe in Peruna, Khorsa, Mokosh and Simargl, and in fairies, whom the ignorant say, the triune sisters consider them goddesses and offer sacrifices to them and cut chickens, they pray to fire, calling it Svarozhich, they deify garlic, and when one has a feast, then they put it in buckets and bowls, and so they drink, rejoicing in their idols".[11]

Criticism

According to philologist Viktor Zhivov, the synthesis of pagan and Christian cultural elements is typical of all European cultures; dual faith is not unique to Russian spirituality.[12]

American researcher Eve Levin believes that a significant part of medieval Russian folk Orthodoxy has Christian origins. Levin cites Paraskevi of Iconium, who was considered a Christian replacement for the goddess Mokosh in folk religion.[13]

Ethnographer Alexander Strakhov writes, "Since the nineteenth century, we have been quite convinced that it is worth stripping off the pagan rites superimposed, in a thin layer, the Christian colors, so that the features of ancient pagan beliefs are revealed."[14]

Strakhov disagrees; according to his monograph, The Night Before Christmas, "Under the 'pagan' appearance of a rite or belief there is often a quite Christian basis."

Folklorist Alexander Panchenko writes, We do not have many methods for determining the antiquity of certain phenomena of mass (especially oral) culture. "Archaism" of many cultural forms investigated by domestic ethnologists and folklorists is a scientific illusion. What was considered a "legacy of paganism" is often a comparatively late phenomenon that emerged in the context of Christian culture ... I think the pursuit of the archaic is another way of constructing the "alien" – that "obscure object of desire" of colonial anthropology.[15]

According to historian Vladimir Petrukhin, there was no pagan worldview separate from the Christian one during the Russian Middle Ages; the people perceived themselves as Christians. Customs considered relics of paganism had a literary origin or belonged to the secular culture of the time.[16]

Folklorist Nikita Tolstoy, noting the primitivism of dual faith, proposed the term troeverie ("triple faith"). The third component of the worldview of the Russian Middle Ages was the folk, "non-canonical" culture of Byzantium, the Balkans and Europe, which came to Russia with Christianity in the form of skomorokhs, Foolishness for Christ, and koliada.[17] It has also been applied to the mixture of Russian folk beliefs with those of other cultures such as Chinese folk religion.[18]

Slavic traditions

Formation

The spread of Christian teaching in Russia (especially early) influenced the people's mythopoetic worldview;[2] folk Orthodoxy became part of Russian culture, preserving tradition. Russia's original Slavic beliefs, woven into folk orthodoxy, differed in a number of ways from the official religion.[19] Nikolai Semyonovich Gordienko, following Boris Rybakov, believed that in Russia "there has been a long, centuries-long coexistence of Byzantine Christianity with Slavic paganism: at first as separate faith systems functioning in parallel, and then – up to the present – as two components of a single Christian religious-celebrity complex, called Russian Orthodoxy".[20] According to Gordienko, dual faith (first explicit and then hidden) was formally overcome by Russian Orthodoxy through accommodation: "Byzantine Christianity did not eliminate Slavic paganism from the consciousness and everyday life of the peoples of our country, but rather assimilated it by including pagan beliefs and rituals in its belief-cultural complex".[21] The non-canonical culture of the Balkans and Byzantium (which came to Russia with Christianity) was also an influence,[17] as were the Finno-Ugric, Scandinavian, Baltic and Iranian peoples bordering the East Slavs.[22][23] This fact calls into question the adequacy of the term "Dvoeverie" in relation to "non-canonical" beliefs. However, some authors, relying on already outdated studies, even point to the "leading" role of Slavic paganism in "folk Orthodoxy".[24]

In itself, "folk Orthodoxy" is a dynamic form in which both archetypal mythopoetic ideas and Orthodox canons are combined.[25] According to historian Vladimir Petrukhin, "Since both the sermons against pagans and the Russian Primary Chronicle – the Tale of Bygone Years (PVL) were the result of the "reception" of Byzantine samples – the works of the church fathers (primarily, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom) and Byzantine chronicles (primarily, John Malala and George Amartola) – then the proper Old Russian folklore motives, names of pagan gods, etc. were included in the Byzantine and Biblical "literary" context".[26] Another follower of the concept of "Dual Faith" Igor Froyanov noted the more pagan nature of society, especially the peasantry in Russia up to the XIV-XV centuries, relying primarily on the hypotheses of B. A. Rybakov, as well as the nature of warfare, the tradition of drunken feasts at the prince and other indirect signs.[27] However, only one or two mentions of Rusali, and that as dates of the agricultural calendar, are found in the birch bark charters. Even accusations of "witchcraft", which is not necessarily synonymous to "paganism", are found in no more than two of more than 450 deciphered documents. In contrast, the use of the Orthodox calendar to describe the agricultural cycle of work appears in the thirteenth century and points to the spread of Christianity at that time. By the end of the fourteenth century, peasants generally refer to themselves as "Christians," which emphasizes their assimilation of Christian identity. Urban dwellers identify themselves as Christians no later than the twelfth century.[28]

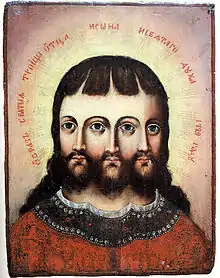

Mixed-hypostatic icons of the Trinity were borrowed from Catholic countries.[29] In Russia, due to their contradiction to the canon, they were officially banned. Such icons did not reflect Russian folk beliefs but were a subject of folk religion.[30] Popular Orthodoxy is a social and cultural phenomenon. It developed gradually with the spread of Christianity in Russia. At first, "the masses had to at least minimally master the ritual and dogmatic foundations of the new religion".[31]

The people's ideas about God and His Trinity generally coincided with the Christian doctrine: God is the Creator, Provider, and Judge of the world; God is one and in three persons. But already the more specific question of the essence of the trinity of God put the peasantry in a stalemate.[31] Thus, the conception of the trinity of God was essentially reduced to the belief of the existence of three separate persons of the Trinity. With the name of God the Father, the peasants connected more the idea of the paternal relationship of God to men, rather than the personal characteristic of the first person of the Trinity. God the Son was thought of as the Lord Jesus Christ, not as the second person of the Trinity eternally begotten of the Father. Especially vague and indefinite was the idea of the Sacred Spirit.[31] It is no coincidence, therefore, that the result of the studies of the people's perceptions of God undertaken by the church author Alexei Popov concluded that "the people's view of the trinity of the persons of God is not complete and sometimes seems somewhat hesitant and confused, but nevertheless the people distinguish the persons of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The Russian people recognize one God, although along with this, without being aware of his notion, he also recognizes the three Persons of the Holy Trinity".[32] And in the 19th century, the basic dogma of Christianity about the trinity of God was not mastered by Russian peasants. In explaining this fact, church authors referred to the lack of Christian education of the peasants.[31]

The theological-dogmatic category of the Trinity turned out to be reinterpreted on a domestic level. In the research literature, this phenomenon is associated with the coincidence Pentecost and the cycle of ancient Slavic Green week feasts. The associative-integrative nature of medieval thinking and the entire folk culture manifested itself in the perception of the Trinity as Mother of God.[33] In oral poetry, the Trinity was perceived as the Mother of God, which is reflected, in particular, in some Green week songs with the famous opening "Bless, Trinity-Mother of God...", sung as early as the second half of the nineteenth century. This image of the Holy Trinity found expression in iconography as well.[34] This is an example of everyday folk myth-making, which perceived the Christian dogma through the prism of pagan concepts. A. N. Veselovsky wrote: "Thus a whole new world of fantastic images had to be created, in which Christianity participated only in materials and names, while the content and the very construction came out pagan".[34]

The peculiar intertwining of superstition with Christian doctrine is explained by the fact that peasants were attracted to Christianity not by its dogmatic side (many peasants did not understand Christian dogmas), but by its purely external, ceremonial.[35] According to Archbishop Macarius Bulgakov, author of the multi-volume History of the Russian Church, many of the Christians practically remained pagans: they performed the rites of the Holy Church but retained the customs and beliefs of their fathers.[36]

In the USSR, the question of everyday Orthodoxy as a functioning system and as a socio-cultural and socio-historical phenomenon remained insufficiently studied.[37]

Popular religiosity differed from and even opposed official Christianity. At the same time, the church accepted some folk worship and cults, making adjustments to its teachings. For example, the popular cult of the Virgin Mary by the twelfth century was supported and developed by the church. Under the influence of popular veneration of "holy poverty" and notions of social justice, by the twelfth century the emphasis of veneration shifts from the cult of the formidable God the Father, and Christ-Pantocrator, as rulers of the world, to the cult of Christ-Redeemer.[38]

Domestic Orthodoxy is a peculiar, created by peasantry, "edition" of the Christian religion, condemned by the Church. Christian religion as asserted by clergy, could not penetrate into the depths of the life of the Russian village, and having taken the form of agrarian and domestic beliefs, was the source and the ground of the appearance of superstition representations, magic actions, peculiar interpretations of the real world.[39]

As far back as the nineteenth century, it was noted that Christian holidays were celebrated by the people as "kudes" – rituals that were "rude" and "dirty" and caused the most serious condemnation by the church.[40] And in the early 20th century, it was said about the Russian people:

Russian people understand nothing in their religion ... they mix God with St. Nicholas and are ready even to give the latter an advantage ... The tenets of Christianity are completely unknown to them

— Missionary Review, 1902, vol. II

According to some researchers, folk religious ideas should not be understood as "two-faith", "layering and parallel existence of the old and the new", not as a haphazard formation consisting of the pagan cultural layer proper and the later ecclesiastical overlays, but as "people's monotheism", a holistic worldview, not disintegrating into paganism and Christianity, but forming an integral, though fluid, and in some cases somewhat contradictory system.[41]

Ethnography

Ethnography in late-nineteenth-century Ukraine documented a "thorough synthesis of pagan and Christian elements" in Slavic folk religion, a system often called "double belief" (Russian: dvoeverie, Ukrainian: dvovirya).[42] According to Bernshtam, dvoeverie is still used to this day in scholarly works to define Slavic folk religion, which is seen by certain scholars as having preserved much of pre-Christian Slavic religion, "poorly and transparently" covered by a Christianity that may be easily "stripped away" to reveal more or less "pure" patterns of the original faith.[43] Since the collapse of the Soviet Union there has been a new wave of scholarly debate on the subjects of Slavic folk religion and dvoeverie. A. E. Musin, an academic and deacon of the Russian Orthodox Church, published an article about the "problem of double belief" as recently as 1991. In this article he divides scholars between those who say that Russian Orthodoxy adapted to entrenched indigenous faith, continuing the Soviet idea of an "undefeated paganism", and those who say that Russian Orthodoxy is an out-and-out syncretic religion.[44] Bernshtam challenges dualistic notions of dvoeverie and proposes interpreting broader Slavic religiosity as a mnogoverie ("multifaith") continuum, in which a higher layer of Orthodox Christian officialdom is alternated with a variety of "Old Beliefs" among the various strata of the population.[45]

According to Ivanits, nineteenth- and twentieth-century Slavic folk religion's central concern was fertility, propitiated with rites celebrating death and resurrection. Scholars of Slavic religion who focused on nineteenth-century folk religion were often led to mistakes such as the interpretation of Rod and Rozhanitsy as figures of a merely ancestral cult; however, in medieval documents Rod is equated with the ancient Egyptian god Osiris, representing a broader concept of natural generativity.[46] Belief in the holiness of Mat Syra Zemlya ("Damp Mother Earth") is another feature that has persisted into modern Slavic folk religion; up to the twentieth century, Russian peasants practiced a variety of rituals devoted to her and confessed their sins to her in the absence of a priest. Ivanits also reports that in the region of Vladimir old people practiced a ritual asking Earth's forgiveness before their death. A number of scholars attributed the Russians' particular devotion to the Theotokos, the "Mother of God", to this still powerful pre-Christian substratum of devotion to a great mother goddess.[46]

Ivanits attributes the tenacity of synthetic Slavic folk religion to an exceptionality of Slavs and of Russia in particular, compared to other European countries; "the Russian case is extreme", she says, because Russia—especially the vastness of rural Russia—neither lived the intellectual upheavals of the Renaissance, nor the Reformation, nor the Age of Enlightenment, which severely weakened folk spirituality in the rest of Europe.[47]

Slavic folk religious festivals and rites reflect the times of the ancient pagan calendar. For instance, the Christmas period is marked by the rites of Koliada, characterized by the element of fire, processions and ritual drama, offerings of food and drink to the ancestors. Spring and summer rites are characterized by fire- and water-related imagery spinning around the figures of the gods Yarilo, Kupala and Marzanna. The switching of seasonal spirits is celebrated through the interaction of effigies of these spirits and the elements which symbolize the coming season, such as by burning, drowning or setting the effigies onto water, and the "rolling of burning wheels of straw down into rivers".[42]

Slavic saint cults

With the spread of Christianity in Russia the former beliefs of the Slavs did not disappear without a trace.[48] The interaction of pagan and Christian cultures led to the transformation of the images of Christian saints in popular culture. They turned out to be "substitutes" for pagan gods and some pre-Christian traits[49][50] were transferred to them.

The Slavs' folk representations of Christian saints and their lives sometimes differ greatly from their canonical images. In fairy tale and legend, some of them sometimes organically perform the function of good helpers, and others even play the role of pests in relation to the peasant. This was especially strong in the images of Theotokos, Nicholas the Wonderworker, Elijah the Prophet, George the Victorious, Vlasius, Florus and Laurus, Kasian, Paraskeva Friday, Saints Cosmas and Damian.[49]

Theotokos

The Mother of God was perceived by the Slavs as the patroness of women, women's work, women in childbirth, the protector from trouble, evil forces, misfortune and suffering, the heavenly intercessor, responsive, merciful and compassionate. Therefore, she is often referred to in Apocryphal Prayer, Zagovory, spells. The Virgin Mary is a favorite character in folk legends, often having a bookish apocryphal source.[51]

The patronage of women in childbirth is due to the traditional perception of the maternal beginning in the image of the Mother of God, which is emphasized by the etymological connection of her name with the word "birth". The Virgin Mary was usually approached with a request for help in difficult deliveries, on the day of the Nativity of the Virgin, pregnant women prayed for the easy release from the childbirth. The Virgin Mary was also perceived not only as the Mother of God, but also as the birth mother for all people. In this sense she in peasant consciousness correlated with the Mother of the raw earth. This relationship is also found in the traditional notions of swearing: in the popular environment it was believed that it offends the three mothers of man – the Mother of God, Mat Zemlya and the native mother. The Russians have a well-known saying: when one swears in foul language – "the Mother of God falls face down in the mud".[49]

The connection of the cults of the Mother of God and the Mother of the raw earth was recorded in the 1920s in Pereslavl-Zalessky Uyezd, Vladimir Province. Here during a strong drought the men in despair began beating dry lumps of earth in the fields with beater hammers, to which the women demanded to stop, saying that by doing so they were beating "the Mother of the Most Holy Mother of God herself". The connection of the Virgin with agriculture is evidenced by the timing in some places in Russian rituals relating to the ceremonial beginning of sowing on Blagoveshcheniye. In order to have a good harvest, the grain for sowing was consecrated on this day, and then an icon of the Virgin Mary was placed in the vessel with the grain, and a sentence was pronounced:[49]

Mother of God!

Gabriel the Archangel!

Bless us, bless us, bless us,

Bless us with your harvest.

Oats and rye, barley and wheat

And all manner of livestock!

Nicholas the Wonderworker

Nicholas the Wonderworker is one of the most revered Christian saints among the Slavs. In the East Slavic tradition, the cult of Nicholas is close to the veneration of God (Christ) himself.[52]

According to Slavic folk beliefs, Nikola is the "elder" among the saints, is part of the Holy Trinity and can even succeed God on the throne.[52] A legend from Belarusian Polesie says that "Svyaty Mikola is not only the oldest of all the saints, but he is also the oldest of them <...> Svyaty Mikola is God's heir, when God dies, then Sv. Mikalai the miracle-worker will be god, and not anyone else". About the special veneration of the saint testify the stories of folk legends about how St. Nicholas became a "lord": he prayed so devoutly in church that the golden crown itself fell on his head (Ukr. Carpathian).[53]

In the Eastern and Western Slavs, the image of St. Nicholas in some of its functions ("chief" of the paradise – holds the keys to heaven; transports souls to "the other world"; protects warriors) may be combined with the image of Archangel Michael. In the southern Slavs, the image of the saint as a snake exterminator and "wolf shepherd", converges with the image of Georgy the Victorious.[54]

The main functions of Nicholas (patron of cattle and wild animals, farming, beekeeping, connection with the afterlife, correlation with the relics of the bear cult), the opposition of "merciful" Nicholas to the "terrible" Ilya the prophet in folklore legends indicate, according to Boris Uspenskij, about the preservation in the popular veneration of St. Nicholas of traces of the cult of the pagan deity Velesa.[54]

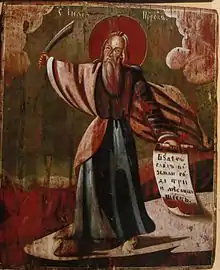

Elijah the prophet

In Slavic folk tradition, Ilya the Prophet is the lord of thunder, heavenly fire, rain, the patron of crops, and fertility. Elijah is a "thunderbolt saint".[55]

According to Slavic folk legends based on the bookish (biblical, bogomils) tradition, Elijah was taken alive into heaven. Until he was 33 years old, Elijah sat sitting and was healed and endowed with great power by God and saint Nicholas the Wonderworker (cf. bogatyr), after which he was taken to heaven (eagle), cf. the epic story of Ilya Murometz. The saint rides through the sky on a fiery (stone) chariot. According to Slavic beliefs, the sun is a wheel from the chariot of Elijah the Prophet, harnessed by fiery (white, winged) horses (V.-Slav.), or on a white horse (Bulgarian), which causes the thunder. The Milky Way is the road on which the prophet rides. In winter, Elijah rides a sleigh, so there is no thunder and thunder (Orlov.). The power of Elijah the thunderer is so great that it must be restrained: God placed on Elijah's head a stone of 40 dessiatin (Orlov.), bound him one arm and leg (Carpathian. ); Elijah's sister Ognyena Maria hid the day of his feast from him, or else he would beat the whole world with lightning for joy (Serbian); St. Elijah has only his left hand; if he had both hands, he would kill all the devils on earth (Banatgers). Before the end of the world, Elijah will descend to the earth and travel around the world three times, warning of the Last Judgment (Orlov.); he will come to earth to die or accept martyrdom by beheading on the skin of a huge ox, which grazes on seven mountains and drinks seven rivers of water; the spilled blood of the prophet will burn the earth (Carpathian). According to a legend from Galicia, the end of the world will come when Ilya "will fall with thunders so much that the earth will be rosipitsi i spalitsi"; cf. the Russian spiritual verse "On the Last Judgement," in variants of which the saint appears as the executor of the will of God, punishing the sinful human race.[55]

Yegoriy the Brave

In the popular culture of the Slavs George the Victorious is called Yegoriy the Brave,[56] George is the protector of cattle, "wolf shepherd", "on spring he unlocks the Earth and releases the dew". In Southern Slavs Gergiev (Yuriev) Day is the main calendar boundary of the first half of the year, together with Mitrovdan it divides the year into two half-years – "Dmitrovsky" and "Yurievsky".[57] According to T. Zueva the image of Yegoriy the Brave in the folk tradition merged with the pagan Dazhbogom.[58]

Two images of the saint coexist in folk consciousness: one of them is close to the Church cult of St. George – the serpent-slyer and Christ-loving warrior; the other, quite different from the first, to the cult of the cattleman and farmer, master of the land, patron of cattle, who opens the spring fieldwork. Thus, in folk legends and religious verses, the feats of the holy warrior Egorii (St. George), who withstood the tortures and promises of the "Tsar of Demianish (Diocletianish)" and struck "the fierce serpent, the fierce fiery one", are glorified. The motif of Saint George's victory is known in the oral poetry of the Eastern and Western Slavs. The Poles have St. Jerzy fighting the "Wawel smok" (the serpent of Krakow Castle). The Russian ecclesiastical verse, also following the iconographic canon, lists Feodor Tiron (see Tale of the Feodor Tirinin's Feats) as a serpent-fighter, whom the Eastern and South Slavic traditions also represent as a rider and protector of cattle.[56]

Another folk image of the saint is associated with the beginning of spring, agriculture, and cattle breeding, with the first cattle drive, which in the eastern and part of the southern Slavs, as well as in eastern Poland often occurs on St. George's Day. In Russian (Kostroma, Tver.) circumambient Yur'ev songs refer to St. Yegorius and St. Makarii:[56]

Yegorius you are our brave one,

Macarius the reverend!

Thou save our cattle.

In the field and beyond the field,

In the woods and beyond the woods,

Under the light of the month,

Under the red sun,

From the wolf of prey,

From the fierce bear,

From the beast of the evil one.

The Croats and Slovenes have a major figure in the rounding of courtyards with the Saint George Songs Green Yuri – a boy covered from head to toe with green branches, representing St. George (cf. bush driving). In the same Croatian songs on St. George's Day, there is sometimes a motif of snake fighting and the snake kidnapping of a maiden. The Slovenes in Pomurje used to lead "Zeleni Jurij" or "Vesnik" (Zeleni Jurij, Vésnik – from the Slovenian dialect vésna "spring") and sing[56]

Original |

Translation. |

The motif of shoeing a horse and going around the fields is characteristic of Bulgarian and Eastern Serbian Yuri songs: "Sveti Giorgi kone kove se from srebro and from zlato..." (St. George horseshoes the horse with silver and gold...)[56]

Original |

Translation. |

In Lower Angara, Yegoriy the Brave was honored as the patron saint of horses; they did not work on horses on his day. In Pirin Macedonia (Petrich) it was believed that St. George was the lord of spring rain and thunder: together with prophet Elijah he rode a horse across the sky, and this made thunder be heard. In the villages near Plovdiv the saint was perceived as the master and "holder" of all waters: he killed the serpent to give the people water.[56]

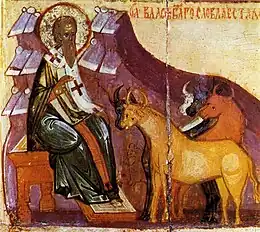

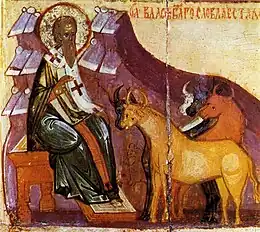

Blaise as a cattle god

In Slavic folk tradition saint Vlasius is the patron saint of cattle,[59] "washing milk from cows" at the end of winter.[60] Traditional representations of St. Vlasius go back to the image of the Slavic cattle god Volos. The combination of the images of a pagan deity and a Christian saint in the popular consciousness was probably facilitated by the sonic proximity of their names. In Russia, with the Baptism of Russia churches of Saint Blasius were often erected on places of pagan worship of Volos.[61]

According to the hagiography, during the persecution of Christians under the Roman emperor Licinius, Saint Blasius hid in the wilderness and lived on Mount Argeos in a cave, to which wild beasts meekly approached, submitting in all things to Blasius and receiving from him blessings and healing from illnesses. The motif of the patronage of cattle is reflected in the iconography of Saint Blaise. He was sometimes depicted on a white horse surrounded by horses, cows, and sheep, or only cattle. In Slavic folk tradition St. Blasius was called "the cow god," and the day of his memory was "the cow holiday".[59] In Novgorod on Blaise's Day, they brought cow's oil to his image. The Belarusians had a special meal and rode young horses on St. Vlasii's Day ("horse's holy day"). According to the northern Ukrainian beliefs, Vlasius "envied the horned cattle. In Siberia, the feast of St. Vlasii was celebrated as the patron of cattle. In eastern Serbia (Bujak), Vlasyev day was considered the feast of oxen and cattle (Serbian: goveђa glory, and on this day the oxen were not harnessed.[59]

If Vlasiev day coincided with Maslenitsa, then they used to say: "On the day of Vlasia, the butter kayushom" [62] (Belarusian.) – On Vlas take with a ladle of oil. ",[63] and on Onisimus the Hornless, "winter becomes hornless".[64]

Paraskeva Friday

The cult of saint Paraskeva of Iconium is based on the personification of Friday, known in Russian as Pyatnitsa, as a weekday.[65] According to a number of researchers, some signs and functions of the main female deity of the East Slavic pantheon, Mokoshi, were transferred to Paraskeva Friday: connection with female works (spinning, sewing, etc.), with marriage and childbearing, with the earthly moisture.[65] Also correlated with Theotokos, Week and Saint Anastasia.[65]

The image of Paraskeva Friday, according to folk representations is markedly different from the iconographic one, where she is depicted as an ascetic-looking woman in a red omophorion. Folk imagination endowed her with demonic features: tall stature, long loose hair, large breasts, which she throws behind her back, and others, which brings her closer to female mythological characters such as Doli, Death, and the Mermaid.

There was a ritual of "driving Pyatnitsa", recorded in the 18th century: "In Little Russia, in the Starodubsky regiment on a feast day a plain woman named Pyatnitsa is led through the church and during the church, her people honor her with gifts and with the hope of some benefit".[66] In the stories, Paraskeva Pyatnitsa spins the yarn left by her mistress (similar to domovyi, kimora, mar),[65] and punishes the woman who dared in spite of the Friday ban on spinning, thread winding, and sewing: tangles the threads, may skin the offending woman, take away her sight, turn her into a frog, throw forty spindles into the window with orders to strain them until morning, etc. [49]

According to beliefs, Paraskeva Friday controls the observance of other Friday prohibitions as well (washing laundry, bleaching canvases, combing hair, etc.).[67]

According to Ukrainian beliefs, Friday walks stabbed with needles and spindles of negligent hosts who have not honored the saint and her days. Until the 19th century, the custom of "leading Friday" – a woman with her hair loose was preserved in Ukraine.[68]

In bylichka and spiritual verses, Paraskeva Friday complains that she is not honored by not observing the prohibition on Fridays – they prick her with spindles, spin her hair, clog her eyes Kostrakostra. According to beliefs, Paraskeva Friday is depicted on icons with spokes or spindles sticking out of her chest (cf. images of Seven-Strength Icon , Softening of Evil Hearts).[69]

Saint Nedelya - Personification of the week

In Slavic folk representations, a character, a personification of the day of week – Sunday. It is associated with the saint Anastasia (in the Bulgarians, also with the saint Kiriakiya[70]). Prohibitions against various kinds of work are associated with the veneration of Saint Nedelya (cf. the origin of the Slavic week from not to do).

The Belarusians of Grodno province told us that the day of rest, nyadzel, was given to the people after a man once hid the holy Week from the dogs that pursued it; before that there were only weekdays. The Ukrainians of Volhynia said that God gave Saint Nedelya a whole day, but told her herself to see to it that people did not work on that day. According to Croatian beliefs, Saint Nedelya has no hands, so it is especially sinful to work on this day.

Saint Nedelya comes to those who violate the prohibition of work on Sunday (spinning, weaving, treading flax, digging the ground, going to the forest, working in the fields, etc.). Saint Nedelya appears as a woman (girl) in white, gold or silver clothing (bel.), with a wounded body and complains that she is poked with spindles, spun her hair (while pointing to her torn scythe – Ukr.), chopped, cut, etc. In the Ukrainian legend, a man meets a young woman on the road, who confesses that she is Nedelya, which people "spelt, boiled, fried, scalded, sliced, eaten" (Chigirinskiy uyezd). In the West-Belarusian legend, Saint Nedelya appears paired with the dressy and beautiful '[Jew's Nedzelka]' (that is, the Sabbath, revered by Jews) and complains that the Jews revere their "week" and that "you do everything in the week, then my body was purely paabrava".

The veneration of Saint Nedelya is closely related to the veneration of the other personified days of the week, Wednesday and Friday, which in popular beliefs are related by kinship ties. The Serbs believe that Paraskeva Friday is the mother or sister of Saint Nedelya (cf. the successive days of St. Paraskeva Friday – 28.X/10.XI and St. Anastasia – 29.X/11.XI). According to the Hutsul people "Week is the Mother of God" (the Mother of God asked for protection on all the days of the week, agreed week, i.e., Sunday; cf. the pan-Slavonic notions of the Virgin Mary, Saint Paraskeva Friday, Saint Anastasia as patronesses of women and women's work, and similar prohibitions associated with the Virgin feasts, Friday and Sunday).[71]

Apostles Peter and Paul

In Slavic tradition Peter and Paul are paired characters (cf. Saints Cosmas and Damian, Flor and Laurus), who may often appear in a single image: Peter-Paul, Peter-Paulo, Petropavlava. The Bulgarians considered them brothers, sometimes even twins, who had a sister – Saint Helen or Saint Mary (Fire). Peter is the younger brother and the kinder: he allows the farmers to work on their feast day. Paul is the eldest; he is formidable and severely punishes those who violate holiday customs by sending thunder and lightning from the sky, burning sheaves. According to Serbian legend, "the division of faiths into Orthodox and Catholic occurred after a quarrel of the apostles: Peter declared himself Orthodox (Serbian), and Paul said that he was Catholic (Šokci). In the representation of the Slavs, Peter and Paul occupy a special place, acting as guardians of the keys to paradise (cf. the Belarusian name of the constellation Swan – Belarusian: Pyatrovaya stick, which is also perceived as a key to paradise). The Bulgarians also considered St. Peter the guardian of the Garden of Eden, guarding the golden tree of paradise, around which the souls of dead children fly in the form of flies and bees.[72]

In the traditional worldview of the Russian people, the Apostle Peter was among the most revered saints. In tales and bylichkas he appears under the name of the apostle-king.[73]

There was a belief among the Gutsul that St. Peter kept the keys of the land all year round, and only in spring did Saint George the Victorious take them from him; on Peter's day the keys are returned to Peter, and then the autumn[74] comes.

In Serbia, the Apostle Peter was pictured "riding a golden-horned deer across the heavenly field over the sprouting earthly fields".[75]

On icons and rituals

The Soviet art historian M. V. Alpatov believed that among Old Russian icons one could distinguish those that reflected folk ideals and that the folk idea of saints was especially clearly manifested in icons depicting patrons of cattle (George, Vlasius, Florus, and Laurus) and also in icons of Elijah the Prophet, a kind of "successor" to the god of thunder and lightning Perun. In addition, he admitted that some ancient Russian icons reflected folk dual beliefs, including the cult of Mother of the Raw Earth.[76]

According to Doctor of Historical Sciences Lyubov Emelyakh, this cult of the mother earth, the patroness of crops, which once existed among the Slavs, reflects the icon of the Conqueror of Bread painted in the late 19th century.[77]

Nikita Tolstoy examines the rites of slumping and girding the temple, rites of invocation of rain,[78] rites connected with protection from thunder and hail,[79] and some others as a symbiosis of Christian and pre-Christian customs.

Folk prayers

Folk Christian prayers include canonical prayers that are common in popular culture, fragments of Christian Worship church services, endowed in popular circles with apotropaic function (that is, having noncanonical application), and noncanonical prayers proper. The functioning and consolidation of folk prayers in tradition as apotropei (amulets rituals) is largely determined not by their own semantics, but by their high sacred status. These texts themselves do not possess apotropaic semantics, and their use as amulets is determined by their ability, as it is believed, to prevent potential danger. The main part of the corpus of such texts is of bookish origin and penetrated into the folk tradition with acceptance of Christianity, a smaller part is authentic texts.

In contrast to Trebniks (containing, in particular, canonical prayers), where each prayer has a strictly defined use, in popular culture, canonical Christian prayers usually have no such fixation but are used as universal apotrophes for all occasions. The main reason for this is that the circle of canonical prayers known in traditional culture is extremely narrow. These include such common prayers containing apotropaic semantics as "Let God arise, and His enemies are made waste..." (in the East Slavic folk tradition usually referred to as the "Sunday Prayer") and the 90th Psalm "Alive in aid..." (usually rearranged by popular etymology as "Living Helpers"), as well as "Our Father" and "Virgin Mary, Rejoice..." (in the Catholic tradition, "Zdrowiaś, Maria..."). The Lord's Prayer is a universal apotheosis, which is explained by its unique status as the only "nonvirtuous" prayer, that is, given to people by God himself, Christ. At the same time, this prayer is a declaration of man's belonging to the Christian world and his stay under the protection of heavenly powers.

Fragments of a church service, which are in no way connected in meaning with the apotropaic situation in which they are used, also function as amulets. For example, the beginning from Liturgy of St. Basil the Great "On you rejoice, Graceful, every creature, the angelic assembly and the human race..." may be read by the master during the driving of the cow to pasture.[80]

Apocryphal Prayers (in Index of Repudiated Books, "false prayers") are prayers modeled after those of the church, But containing a large number of insertions from folk beliefs, incantations, incantations, in some cases reworkings or extracts from apocrypha.[81] Apocryphal prayers and hagiographies adapted for "protective" purposes are much more common in the folk tradition than canonical church texts. Apocryphal prayers are mostly texts of bookish origin. Some of their versions may retain the genre form of a prayer, while others take on the features of Zagovory. Often transcribed and used as a talisman and amulet, which were worn with national cross or kept in the house.[80]

Most often there are prayers-consecrations for fever. The text usually mentions Saint Sisinius and Likhoradka.[81] Exceptional in its prevalence is the apocryphal Prayer of the Dream of the Virgin Mary, which contains the account of Our Lady of the tortures of Christ on the cross. The text is known in both Catholic and Orthodox traditions in numerous variations. In Eastern Slavic folklore, it dominates and is revered along with the Lord's Prayer and Psalm 90. Most often it was recited before going to bed as a general apotheosis text. The text of the "Dream of the Virgin Mary" was worn as a talisman in the Ladanka together with the body cross. Among the texts of bookish origin in both Orthodox and Catholics, a significant proportion are apocryphal prayers that contain an account of the life and crucifixion of Christ or other significant events of Sacred History. The account of Christ's tortures on the cross for the salvation of mankind projects the idea of universal salvation into a specific situation, so it is believed that in some cases a reference to events from the life of Christ[80] is sufficient for salvation from danger.[80]

Significance

The Church could convert the pagans to the veneration of the Christian God and saints but was unable to solve all the pressing problems and explain in detail from the Christian perspective how the world around them was arranged, due to the lack of a sufficiently developed and extensive system of education. The popular religious-mythological system remained in demand because of the etiological (explanatory) function of myth. The Christian religion clarified what should be believed and established a system of behavior and values in relations between people and with the nascent state, while folk myths and representations (above all the basic layer constituting lower mythology) answered other pressing questions.[82]

In modern times

In modern times there has been a disintegration of the peasant environment, which retained "pagan relics" (folk Christianity) that had performed important functions in it. Under the new conditions, these cultural elements lost their functions and ceased to be necessary.

In Eastern Slavs, in addition to the disintegration of the peasant way of life, the interruption of the folk-Christian tradition was facilitated by the radical transformation of the traditional way of life that took place during the Soviet period of our history. In the course of the large-scale social, economic, and cultural transformations in the USSR (urbanization, internal migration, the development of education, anti-religious propaganda, etc.) folk orthodoxy was rapidly disappearing along with relics of the pre-Christian picture of the world. The accessible Soviet educational system formed a scientific picture of the world that left no room for traditional myths, which previously existed in the form of various superstitions, omens, and bylaws.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, with the support of the authorities, Orthodox Christianity regained its importance in public life. While Orthodoxy has preserved its norms and traditions, which can be brought back up to date, folk-Christian beliefs and ritual practices have been almost completely lost and forgotten under the influence of atheist propaganda and the country's accelerated modernization policy, and have no chance of revival.

"Paganism," to the spread of which some Orthodox authors point in modern society, is not a further development of the ancient religious beliefs of the Eastern Slavs, but a consequence of the primitivization of the mass consciousness, the dissociation of the scientific picture of the world into separate elements, no longer united by any philosophical idea. To such "paganism" Orthodox authors refer a variety of phenomena incompatible with the canons of Abrahamic religions – horoscopes and magic practices, ufology, worship of famous brands, etc. These beliefs and perceptions are a product of globalization and have no connection with the local folk beliefs of the past.[83] They are conflated with such a phenomenon as itseism, a belief in something indefinite.[84][85]

In Ukraine Folk Orthodoxy is seen as having increased in the 2000s[86]

See also

- Folk Catholicism

- Interpretatio Christiana

- Christian mythology

- Religion in Abkhazia

- Russian menologion

- Friday calendar

- Lower mythology

- Thursday salt

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Blagojević, Mirko; Todorović, Dragan (2011). Orthodoxy from an Empirical Perspective. ISBN 978-86-82417-29-3.

- 1 2 http://vestnik.yspu.org/releases/2012_3g/46.pdf

- ↑ Shtyrkov, S. А. "After folk religiosity". Dreams of the Virgin Mary: Studies in the Anthropology of Religion. Edited by J. V. Kormina, Alexander Alexandrovich Panchenko, S. A. Shtyrkov. Saint Petersburg (2006), pp. 7–18.

- ↑ Levin 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ "Dvoeverie".

- ↑ Jakobson, Roman (1985). Contributions to comparative mythology ; Studies in linguistics and philology, 1972-1982. Stephen Rudy. Berlin: Mouton. ISBN 978-3-11-085546-3. OCLC 619443480.

- ↑ Celtic Mythology: Encyclopedia – Moscow: EXMO (2004), p. 447.

- ↑ "obo-vsem-ponemnogu-ot-olechki.com". obo-vsem-ponemnogu-ot-olechki.com.

- ↑ А . А . Лукашевич. Всех святых Неделя // Православная энциклопедия. — Москва, 2005. — Т. IX : "Владимирская икона Божией Матери — Второе пришествие". — С. 706–707. — 752 с. — 39 000 экз. — ISBN 5-89572-015-3.

- ↑ Tolstoy 2003, p. 12-13.

- ↑ Villo Johannes Mancicca, Religion of the Eastern Slavs. Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences (2005), p. 137.

- ↑ Zhivov, Viktor. "Dvoeverie and the peculiar character of Russian cultural history". Investigations in the History and Prehistory of Russian Culture. M.: Languages of Slavic Culture (2002), pp. 306–316.

- ↑ Levin 2004, pp. 11–37.

- ↑ Strakhov A. B. Night before Christmas: folk Christianity and Christmas rituals in the West and among the Slavs. — Cambridge: Cambridge-Mass., 2003.

- ↑ "Modern trends in anthropological research" Anthropological Forum (2004), No. 1, p. 75.

- ↑ Petrukhin, Vladimir Yakovlevich. "Ancient Russia : People, Princes, Religion" in The History of Russian Culture, vol. 1 (Ancient Rus). Moscow: Languages of Russian Culture (2000), pp. 11–410.

- 1 2 Tolstoy 2003, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ "Magic, Demonology and Visions in the Culture of the Trekhrechye Russians".

- ↑ "Автореферат диссертации на соискание ученой степени кандидата искусствоведения Москва 2012". 2014-11-11. Archived from the original on 2014-11-11. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ Gordienko 1986, p. 95.

- ↑ Gordienko 1986, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20180128021152/http://vkist.ru/5303/5303.pdf

- ↑ Levin 2004, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Zhegalo (2011). НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ АСПЕКТ МОТИВА ЧУДА В БЕЛОРУССКИХ И РУССКИХ БЫЛИЧКАХ [National aspect of the miracle motif in Belarusian and Russian bylichkas] (PDF). Vydavecki centr BDU. p. 61. ISBN 978-985-476-946-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-01.

- ↑ "Автореферат диссертации на соискание ученой степени кандидата искусствоведения Москва 2012". 2014-11-11. p. 211. Archived from the original on 2014-11-11. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ "Двоеверие (Русь). В. Петрухин. "Проводы Перуна": древнерусский "фольклор" и византийская традиция". ec-dejavu.ru. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ "Начало христианства на Руси". slavya.ru. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ Levin 2004, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Sofronova M. N. Formation and development of painting in Western Siberia in the XVII – the beginning of the XIX century. Dissertation in Art History. Barnaul, 2004.

- ↑ Antonov D. I., Mayzuls M. R. Демоны и грешники в древнерусской иконографии : Семиотика образа. М. : Indrik, 2011].

- 1 2 3 4 Tultseva 1978, p. 32.

- ↑ http://www.knigafund.ru/books/20237 pp=57–58

- ↑ Tultseva 1978, p. 33.

- 1 2 Veselovsky A. Ya. Slavic legends about Solomon and Kitovras. Sobr. op. — Pg. , 1921. - T. 8.

- ↑ Ю, Садырова М. (2009). "Духовная жизнь русского крестьянства на рубеже XIX XX веков (по материалам Пензенской губернии)". Известия Пензенского государственного педагогического университета им. В. Г. Белинского (15): 128. ISSN 1999-7116.

- ↑ Kryanev Yu. V., Pavlova T. P. Dvoeverie in Russia // How Russia was baptized. – Moscow, 1990. – P. 304-314.

- ↑ Tultseva 1978, p. 31.

- ↑ "Глава 20. Христианство, церковь и ереси в средние века (Уколова В.И.) [1990 - - История средних веков. Том 1]". historic.ru. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ "Скачать Зимний период русского народного земледельческого календаря XVI - XIX веков - Чичеров В.И." 2013-10-12. Archived from the original on 2013-10-12. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ SovremennikPreobrazhensky N. S. (N. Pr-sky). Bath, games, listening and 6th January. (Ethnographic essays of the Kadnikovsky district) // Sovremennik : journal. - 1864. - T. 10 . - S. 499-522 .

- ↑ http://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/didakticheskiy-potentsial-narodnogo-pravoslaviya-v-obuchenii-russkomu-yazyku-kak-inostrannomu#_=_ p=91

- 1 2 Ivakhiv 2005, p. 212.

- ↑ Bernshtam 1992, p. 35.

- ↑ Rock 2007, p. 110.

- ↑ Bernshtam 1992, p. 44.

- 1 2 Ivanits 1989, p. 15.

- ↑ Ivanits 1989, p. 3.

- ↑ Волошина, Т. А.; Астапов, С. Н. (1996). Языческая мифология славян. Ростов н/Д: Феникс.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Madlevskaya; et al. (2007). Власий — скотий бог.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Moroz, Andrey (2009). "Святые Русского Севера. Народная агиография. М.: ОГИ".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Slavic Antiquities : Ethnolinguistic Dictionary Virgin Mary

- 1 2 Belova 2004, p. 398.

- ↑ Belova 2004, pp. 398–399.

- 1 2 Belova 2004, p. 399.

- 1 2 Belova 1999, p. 405.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tolstoy Slavic Antiquities : Ethnolinguistic Dictionary George

- ↑ Dmitry St. day / TA Agapkina // Slavic Antiquities : Ethnolinguistic Dictionary: in 5 volumes / under the general. ed. N.I. Tolstoy ; Institute of Slavic Studies RAS . -M . : Interd. relations , 1999. - T. 2: D (Giving) - K (Crumbs). — P. 93–94. — ISBN 5-7133-0982-7

- ↑ Zueva T. V. Ancient Slavic version of the fairy tale "Wonderful Children" Archived 2018-06-19 at the Wayback Machine // Russian speech, 3/2000 – P. 95

- 1 2 3 Tolstoy Slavic Antiquities : Ethnolinguistic Dictionary Blaise

- ↑ Кляус В. Л. (1997). Указатель сюжетов и сюжетных ситуаций заговорных текстов восточных и южных славян. М.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Madlevskaya; et al. (2005). Russkai︠a︡ mifologii︠a︡ : ent︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡. Elena Madlevskai︠a︡, Елена. Мадлевская. Moskva. ISBN 5-699-13535-9. OCLC 70216827.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Беларускі народны каляндар". 2012-05-11. Archived from the original on 2012-05-11. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ Grushko, Elena (2000). Ėnt︠s︡iklopedii︠a︡ russkikh primet. I︠U︡riĭ. Medvedev. Moskva: ĖKSMO-Press. ISBN 5-04-004217-5. OCLC 49570715.

- ↑ Lavrentieva L. S., Smirnov Yu. I. Culture of the Russian people. Customs, rituals, occupations, folklore. - St. Petersburg. : Parity, 2004. - 448 p. — ISBN 5-93437-117-7

- 1 2 3 4 Paraskeva Pyatnitsa / Levkievskaya E. E., Tolstaya S. M. // Slavic Antiquities : Ethnolinguistic Dictionary: in 5 volumes / under the general ed. N. I. Tolstoy ; Institute of Slavic Studies RAS . - M . : Interd. relations , 2009. - V. 4: P (Crossing the water) - S (Sieve). - S. 631-633. - ISBN 5-7133-0703-4, 978-5-7133-1312-8 Page 631-632

- ↑ http://istoriofil.org.ua/load/knigi_po_istorii/rossii/koldovstvo_i_religija_v_rossii_1700_1740_gg/12-1-0-5962 p=168

- ↑ Щепанская, Т. Б. (2003). Культура дороги в русской мифоритуальной традиции XIX-XX вв [The culture of the road in the Russian mythological and ritual tradition of the 19th-20th centuries]. Традиционная духовная культура славян. Современные исследования (in Russian). Индрик. ISBN 5-85759-176-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01.

- ↑ Voropay O. Zvichaї to our people (Ukrainian) . - Munich: Ukrainian publishing house, 1958. - Vol. 2. - 289 p.

- ↑ Paraskeva Pyatnitsa / Levkievskaya E. E., Tolstaya S. M. // Slavic Antiquities : Ethnolinguistic Dictionary: in 5 volumes / under the general ed. N. I. Tolstoy ; Institute of Slavic Studies RAS . - M . : Interd. relations , 2009. - V. 4: P (Crossing the water) - S (Sieve). - S. 631-633. - ISBN 5-7133-0703-4, 978-5-7133-1312-8

- ↑ Folk culture in Balkanjiit. Scientific ethnographic conference / Presenter and editor: St.n. With. Dr. Angel Goev. - Gabrovo: Architectural and ethnographic complex "Etar", 1996. - T. II. — 308 p.

- ↑ Belova 2004, pp. 391–392.

- ↑ Peter and Pavel / O. V. Belova // Slavic Antiquities : Ethnolinguistic Dictionary: in 5 volumes / under the general. ed. N. I. Tolstoy ; Institute of Slavic Studies RAS . - M . : Interd. relations , 2009. - V. 4: P (Crossing the water) - S (Sieve). - S. 22-24. - ISBN 5-7133-0703-4, 978-5-7133-1312-8 page 22

- ↑ http://www.ethnomuseum.ru/petrov-den

- ↑ Petrov's Day / T. A. Agapkina // Slavic Antiquities : Ethnolinguistic Dictionary: in 5 volumes / ed. ed. N. I. Tolstoy ; Institute of Slavic Studies RAS . - M . : Interd. relations , 2009. - V. 4: P (Crossing the water) - S (Sieve). - S. 24-27. - ISBN 5-7133-0703-4, 978-5-7133-1312-8 page 25

- ↑ Коринфский, А. А. (1901). (in Russian) – via Wikisource.

- ↑ Alpatov M. V. Old Russian icon painting . - M . : Art , 1978. - 310 p.

- ↑ Emelyakh L. I. "Riddles" of the Christian cult. - L . : Lenizdat , 1985. - 187 p. («Загадки» христианского культа.)

- ↑ "Толстой Н. И. Язык и народная культура: Очерки по славянской мифологии и этнолингвистике. М., 1995". Институт славяноведения Российской академии наук (ИСл РАН). 2010-04-26. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ↑ "Толстой Н. И. Очерки славянского язычества. М., 2003". Институт славяноведения Российской академии наук (ИСл РАН). 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- 1 2 3 4 "Левкиевская Е.Е. Народные молитвы и апокрифические тексты как обереги".

- 1 2 Сумцов Н. Ф. Молитвы апокрифические // Новый энциклопедический словарь: В 48 томах (вышло 29 томов). — Санкт-Петербург, Петроград, 1911—1916. – Vol. 26: Maciejewski – Lactic Acid. – 1915. – Stlb. 929–930.

- ↑ Beskov 2015, p. 7.

- ↑ Beskov 2015, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Beskov 2015, p. 9.

- ↑ Tkachenko, A. V. (2012). "Itsism as the main form of religious representations of modern youth". Systemic Psychology and Sociology (6): 112–120.

- ↑ Kononenko, Natalie (2006). "Folk Orthodoxy: Popular Religion in Contemporary Ukraine". Letters from Heaven. pp. 46–75. doi:10.3138/9781442676640-005. ISBN 978-1-4426-7664-0.

Bibliography

- Creuzer, Georg Friedrich; Mone, Franz Joseph (1822). Geschichte des Heidentums im nördlichen Europa. Symbolik und Mythologie der alten Völker (in German). Vol. 1. Georg Olms Verlag. ISBN 978-3-487-40274-1.

- Bernshtam, T. A. (1992). "Russian Folk Culture and Folk Religion". In Balzer Marjorie Mandelstam; Radzai Ronald (eds.). Russian Traditional Culture: Religion, Gender and Customary Law. Routledge. pp. 34–47. ISBN 978-1-56324-039-3.

- Dynda, Jiří (2014). "The Three-Headed One at the Crossroad: A Comparative Study of the Slavic God Triglav". Studia Mythologica Slavica. Institute of Slovenian Ethnology. 17: 57–82. doi:10.3986/sms.v17i0.1495. ISSN 1408-6271.

- Froianov, I. Ia.; Dvornichenko, A. Iu.; Krivosheev, Iu. V. (1992). "The Introduction of Christianity in Russia and the Pagan Traditions". In Balzer Marjorie Mandelstam; Radzai Ronald (eds.). Russian Traditional Culture: Religion, Gender and Customary Law. Routledge. pp. 3–15. ISBN 978-1-56324-039-3.

- Gasparini, Evel (2013). "Slavic religion". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Hanuš, Ignác Jan (1842). Die Wissenschaft des Slawischen Mythus im weitesten, den altpreußisch-lithauischen Mythus mitumfaßenden Sinne. Nach Quellen bearbeitet, sammt der Literatur der slawisch-preußisch-lithauischen Archäologie und Mythologie (in German). J. Millikowski.

- Ivakhiv, Adrian (2005). "The Revival of Ukrainian Native Faith". In Michael F. Strmiska (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. 209–239. ISBN 978-1-85109-608-4.

- Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Belief. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3088-9.

- Pettazzoni, Raffaele (1967). "West Slav Paganism". Essays on the History of Religions. Brill Archive.

- Jakobson, Roman (1985). Contributions to Comparative Mythology: Studies in Linguistics and Philology, 1972–1982. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-085546-3.

- Rock, Stella (2007). Popular Religion in Russia: 'Double Belief' and the Making of an Academic Myth. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-36978-2.

- Veletskaya, N. N. (1992). "Forms of Transformation of Pagan Symbolism in the Old Believer Tradition". In Balzer Marjorie Mandelstam and Radzai Ronald (ed.). Russian Traditional Culture: Religion, Gender and Customary Law. Routledge. pp. 48–60. ISBN 978-1-56324-039-3.

- Vlasov, V. G. (1992). "The Christianization of Russian Peasants". In Balzer Marjorie Mandelstam; Radzai Ronald (eds.). Russian Traditional Culture: Religion, Gender and Customary Law. Routledge. pp. 16–33. ISBN 978-1-56324-039-3.

- Belova (2004). Slavi︠a︡nskie drevnosti : ėtnolingvisticheskiĭ slovarʹ v pi︠a︡ti tomakh. Nikita Tolstoĭ, T. A. Agapkina, S. M. Tolstai︠a︡, Никита Толстой, Т. А. Агапкина, С. М. Толстая, Institut slavi︠a︡novedenii︠a︡ i balkanistiki, Институт славяноведения и балканистики. Moskva: Mezhdunarodnye otnoshenii︠a︡. ISBN 5-7133-0703-4. OCLC 32988664.

- Tultseva (1978). СОВЕТСКАЯ ЭТНОГРАФИЯ (PDF).

- Belova (1999). Slavi︠a︡nskie drevnosti : ėtnolingvisticheskiĭ slovarʹ v pi︠a︡ti tomakh. Nikita Tolstoĭ, T. A. Agapkina, S. M. Tolstai︠a︡, Никита Толстой, Т. А. Агапкина, С. М. Толстая, Institut slavi︠a︡novedenii︠a︡ i balkanistiki, Институт славяноведения и балканистики. Moskva: Mezhdunarodnye otnoshenii︠a︡. ISBN 5-7133-0703-4. OCLC 32988664.

- Tolstoy (2003). "Щепанская Т. Б. Культура дороги в русской мифоритуальной традиции XIX–XX вв". Archived from the original on 2016-05-01. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- Gordienko (1986). ""Крещение Руси"" [Baptism of Rus] (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Levin (2004). "Двоеверие и народная религия в истории России". Archived from the original on 2013-08-16.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Beskov (2015). "Реминисценции восточнославянского язычества в современной Российской культуре (статья первая) \". Colloquium Heptaplomeres (2): 6–18.

Further reading

- Mirko Blagojević; Dragan Todorović (2011). Orthodoxy from an Empirical Perspective. IFDT. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-86-82417-29-3.

- Orthodox Paradoxes: Heterogeneities and Complexities in Contemporary Russian Orthodoxy. BRILL. 2014. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-90-04-26955-2.

- Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer; Ronald Radzai (2016). Russian Traditional Culture: Religion, Gender and Customary Law: Religion, Gender and Customary Law. Taylor & Francis. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-1-315-28843-7.

- Todorović, Ivica (2006). "Christian and pre-Christian dimension of ritual procession" [Christian and pre-Christian dimension of ritual procession]. Glasnik Etnografskog Instituta (54): 271–287. doi:10.2298/GEI0654271T. hdl:21.15107/rcub_dais_8826.

- Todorović, Ivica (2010). "Again on tradition: Strategic concept of the contemporary studies of traditional Serbian spiritual culture: A brief overview" [Again on tradition: strategic concept of the contemporary studies of traditional Serbian spiritual culture: A brief overview]. Glasnik Etnografskog Instituta. 58: 201–215. doi:10.2298/GEI1001201T.

- Kononenko, N., 2006. Folk orthodoxy: Popular religion in contemporary Ukraine

- Stark, L., 2016. Peasants; Pilgrims; and Sacred Promises: Ritual and the Supernatural in Orthodox Karelian Folk Religion (p. 229). Finnish Literature Society/SKS.

- Radisavljević-Ćiparizović, D., 2011. Pilgrimage in empirical perspective: pilgrim's attitudes towards church and folk religiosity and superstition in Serbia. Orthodoxy from an empirical perspective (M. Blagojević, D. Todorović, eds.), Niš: Jugoslovensko udruženje za naučno istraživanje religije, pp. 127–137.

- Filipovic, M.S., 1954. Folk religion among the Orthodox population in eastern Yugoslavia. Harvard Slavic Studies, 2, pp. 359–374.

- Žganec, V., 1956. Folklore Elements in the Yugoslav Orthodox and Roman Catholic Liturgical Chant. Journal of the International Folk Music Council, 8, pp. 19–22.

- Щепанская, Т. Б. (2003). Культура дороги в русской мифоритуальной традиции XIX-XX вв [The culture of the road in the Russian mythological and ritual tradition of the 19th-20th centuries]. Традиционная духовная культура славян. Современные исследования (in Russian). Индрик. ISBN 5-85759-176-7. Archived from the original on 2016-05-01.

- Толстой, Н.И. (2003). Очерки славянского язычества. Традиционная духовная культура славян. Современные исследования. Индрик. ISBN 5-85759-236-4.