.jpg.webp)

The Finding of Moses, sometimes called Moses in the Bullrushes, Moses Saved from the Waters,[1] or other variants, is the story in chapter 2 of the Book of Exodus in the Hebrew Bible of the finding in the River Nile of Moses as a baby by the daughter of Pharaoh. The story became a common subject in art, especially from the Renaissance onwards.

Depictions in Jewish and Islamic art are much less frequent, but some Christian depictions show details derived from extra-biblical Jewish texts. The earliest surviving depiction in art is a fresco in the Dura-Europos synagogue, datable to around 244 AD, whose motif of a "naked princess" bathing in the river has been related to much later art. A contrasting tradition, beginning in the Renaissance, gave great attention to the rich costumes of the princess and her retinue.

Moses was a central figure in Jewish tradition, and was given a variety of different significances in Christian thought. He was regarded as a typological precursor of Christ, but could at times also be regarded as a precursor or allegorical representation of things as diverse as the pope, Venice, the Dutch Republic, or Louis XIV.

The subject also represented a case of a foundling or abandoned child, a significant social issue into modern times. The subject is unusual in standard history painting that it requires a number of female figures, but apart from the baby no male figures are necessary. The opportunity of depicting female nudes was taken by many painters.

Biblical account

Chapter 1:15–22 of the Book of Exodus recounts how during the captivity in Egypt of the Jewish people, the Pharaoh ordered: "Every Hebrew boy that is born you must throw into the Nile, but let every girl live." Chapter 2 begins with the birth of Moses, and continues:

When she [Moses' mother] saw that he was a fine child, she hid him for three months. 3 But when she could hide him no longer, she got a papyrus basket for him and coated it with tar and pitch. Then she placed the child in it and put it among the reeds along the bank of the Nile. 4 His sister [Miriam] stood at a distance to see what would happen to him.

5 Then Pharaoh’s daughter went down to the Nile to bathe, and her attendants were walking along the riverbank. She saw the basket among the reeds and sent her female slave to get it. 6 She opened it and saw the baby. He was crying, and she felt sorry for him. "This is one of the Hebrew babies", she said. 7 Then his sister asked Pharaoh’s daughter, "Shall I go and get one of the Hebrew women to nurse the baby for you?"

8 "Yes, go," she answered. So the girl went and got the baby’s mother. 9 Pharaoh’s daughter said to her, "Take this baby and nurse him for me, and I will pay you." So the woman took the baby and nursed him. 10 When the child grew older, she took him to Pharaoh’s daughter and he became her son. She named him Moses, saying, "I drew him out of the water."[2]

Visualizing the biblical account

The biblical account allows for a variety of compositions. There are several different moments in the story, which are quite often compressed or combined in depictions, and the moment shown, and even the identity of the figures, is often unclear. In particular, Miriam and Moses's mother, traditionally given the name Jochabed, may be thought to be included in the group around the princess.[3]

The Hebrew word usually translated as "basket" in verse 3 can also mean "ark", or small boat.[4] Both vessels appear in art, the ark in fact represented as though made of stiff sheets like solid wood,[5] rather than the ark of bulrushes preferred in recent religious traditions. The basket, usually with a rounded shape, is more common in Christian art (at least in the Western Church), and the ark more so in Jewish and Byzantine art; it is also used in the Islamic miniature described below.[6] In all traditions most depictions show a stretch of open river with few reeds, and the vessel is sometimes seen drifting along in the flow. Exceptions are many 19th-century depictions, and some in late medieval manuscripts of the Bible Moralisée type.

The less common preceding scene of Moses being left in the reeds is formally called The Exposition of Moses.[7] In some depictions this is shown in the distance as a subsidiary scene, and some cycles, mostly illustrating books, show both scenes. In some cases it may be hard to distinguish between the two; usually the Exposition includes Moses' mother and sister, and sometimes his father and other figures.

Rivka Ulmer identifies recurrent "issues" in the iconography of the subject:[8]

- Is Moses in an ark or basket?

- The type of hand gesture of Pharaoh's daughter;

- Who enters the Nile to fetch Moses?

- The number and the gender of the "handmaids";

- What role, if any, is assigned to the River Nile?

- The presence or absence of Egyptian artifacts.

Christian art

Medieval

.jpg.webp)

Medieval depictions are sometimes found in illuminated manuscripts and other media. The incident was regarded as a typological precursor of the Annunciation, and sometimes paired with it. This probably accounts for it being represented as a faded fresco on the rear wall in the Annunciation by Jan van Eyck in the National Gallery of Art, Washington.[9] It might also be regarded as prefiguring "the reception of Christ by the community of the faithful",[10] the Resurrection of Jesus, and the escape from the Massacre of the Innocents by the Flight into Egypt.[11] The princess was often seen allegorically as representing the Church, or earlier the Gentile Church.[12] Alternatively, Moses might be a type for Saint Peter, and so by extension the Pope or Papacy.[13]

Cycles with the life of Moses were not common, but where they exist they may begin with this subject if they have more than about four scenes.[14] The 4th-century Brescia Casket includes it among its 4 or 5 relief scenes from the Life of Moses, and there is thought to have been a depiction (now lost) in the mosaics of Santa Maria Maggiore. There is a 12th-century cycle in stained glass in the Basilica of Saint-Denis which includes it. Cycles are most often paired with one of the Life of Christ, as later in the Sistine Chapel, where the scheme of paired cycles was intended to evoke the oldest Christian art.[15] There are several short cycles in luxury manuscripts of the Bible Moralisée and related types, some of which give the story more than one image.[16]

_cath%C3%A9drale_104.jpg.webp)

The depiction in the 12th-century English Eadwine Psalter has a naked female swimmer in the water, holding the empty ark with one hand, while a clothed female with her feet in the water holds out the baby to the princess, who reclines on a bed or litter. This is part of some 11 scenes of the life of Moses.[17] This may relate to the Jewish visual traditions covered below.[18]

The artist of a French Romanesque capital has enjoyed himself showing the infant Moses threatened by crocodiles and perhaps hippos, as often shown in classical depictions of the Nile landscape. This very rare treatment in fact anticipates modern Biblical criticism: "The cameo of the birth of Moses does not fit the reality of the Nile, where crocodiles would make it dangerous to send a babe in a basket onto the water or even to bathe by the shore: even if the poor were forced to take the risk, no princess would".[19]

12th-century glass, Saint-Denis

12th-century glass, Saint-Denis French Romanesque capital, aware of the classical tradition of the Nilotic landscape

French Romanesque capital, aware of the classical tradition of the Nilotic landscape Moses being "exposed", very much in an "ark", 15th-century miniature

Moses being "exposed", very much in an "ark", 15th-century miniature_(cropped).jpg.webp) The casting-off in the foreground, combined with the finding at rear, 15th-century.

The casting-off in the foreground, combined with the finding at rear, 15th-century.

Renaissance onwards

_-_Nicolas_Poussin_-_Louvre.jpg.webp)

The walls of the Sistine Chapel had facing paired cycles of the lives of Christ and Moses in large frescos, and a Finding by Pietro Perugino began the Moses sequence on the altar wall until it was destroyed in the 1530s to make space for The Last Judgment by Michelangelo, along with a Nativity of Jesus. Perugino's Moses Leaving for Egypt now begins the cycle.[20]

Independent pictures of the subject became increasingly popular in the Renaissance and Baroque periods, when the combination of several elegantly dressed and graceful ladies with a waterside landscape or classical architectural background made it attractive to artists and patrons.[21] For Venice the story had a special resonance with the early history of the city.[22] These paintings were for homes and palaces, sometimes for foundling hospitals.

In addition, child abandonment remained a significant social issue in the period, with foundling hospitals, orphanages specifically for abandoned children, a common focus of charitable activity by the rich.[23] The seal of the London Foundling Hospital showed the scene, and the artist Francis Hayman gave them his painting of the subject, where it hung next to William Hogarth's painting of a slightly later episode of the young Moses and the princess.[24] We know a depiction by Charles de La Fosse was one of a pair of biblical subjects commissioned in 1701 for the billiards room at the Palace of Versailles, paired with Eliezer and Rebecca;[25] possibly the idea was to encourage those winning bets on the game to give their winnings to charity.

The 17th century saw the height of popularity for the subject, with Poussin painting it at least three times,[26] as well as a number of versions of The Exposition of Moses.[27] It has been suggested that the birth in 1638 of the future Louis XIV, whose parents had been childless for 23 years, may have been a factor in the interest of French artists. The poet Antoine Girard de Saint-Amant wrote an epic poem, Moyse sauvé between about 1638 and 1653.[28]

As well as the Catholic countries, there were also a number of versions in Dutch Golden Age painting, where the Old Testament subject was considered unobjectionable, orphanages were run by boards of "regents" drawn from the local wealthy, and the story of Moses was also given contemporary political significance.[29] A painting of the subject shown on the wall behind The Astronomer by Vermeer may represent knowledge and science, as Moses was "learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians".[30]

A painting by Bonifazio de' Pitati of 1545 was perhaps the first large and elaborate treatment of the subject to concentrate on a larger courtly group, entirely using carefully depicted contemporary costumes; he painted at least one smaller similar version of the subject.[31] Bonifazio painted a number of biblical subjects as "modern aristocratic reality", which was already an established pictorial mode in Venice.[32] This is essentially a large aristocratic picnic, complete with musicians, dwarves, many dogs and a monkey, and strolling lovers, where the baby represents an object of polite curiosity.[33] A Niccolò dell'Abbate from c. 1570, now in the Louvre, represents a more classical treatment, with the same "classical" costumes and atmosphere as his mythological subjects. This is closely followed by a number of compositions by Veronese, using the modern dress of his day.[34]

The paintings of Veronese and others, especially Venetians,[5] offered some of the attractions of subjects from pagan mythology, but with a subject with a Christian context. Veronese had been called before the Inquisition in 1573 for his indecorous depiction of the Last Supper as an extravagant festivity mainly in modern dress, in what he renamed The Feast in the House of Levi. Since the Finding certainly called for a party of lavishly dressed court ladies and their attendants, it avoided such objections.[35]

Veronese's costumes, contemporary when he painted them in the 1570s and 1580s, became established as a sort of standard, and were copied and repeated in new compositions by a number of Venetian painters in the 18th century, during a "Veronese revival".[36] The famous painting by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo in the National Gallery of Scotland dates from the 1730s or 1740s, but avoids the fashion of that period and bases its costumes on a Veronese now in Dresden, but in Venice until 1747;[37] another Tiepolo now in the National Gallery of Victoria uses the style of Veronese even more thoroughly.[38]

Nicolas Poussin was attracted both to subjects from the life of Moses and history subjects with an Egyptian setting.[39] His figures wore the 17th-century idea of ancient dress, and the cityscapes in the distant background include pyramids and obelisks, where previously most artists, for example, Veronese, had not attempted to represent a specifically Egyptian setting.[40] An exception is Niccolò dell'Abbate, whose broadly painted cityscape include several prominent triangular elements, although some might be gable-ends. Palm trees are also sometimes seen; European artists, even in the north, had been used to depicting these from painting the "Miracle of the Palm" on the Flight into Egypt in particular.

For good measure the main three versions by Poussin all include a Roman-style Nilus, the god or personification of the Nile, reclining with a cornucopia, in two of them in company with a sphinx,[41] which follows a specific classical statue in the Vatican.[42] His 1647 version for the banker Pointel (now Louvre) includes a hippopotamus hunt on the river in the background, adapted from the Roman Nile mosaic of Palestrina.[43] In a discussion at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture in 1688, the painting was criticised for two breaches of artistic decorum: the princess' skin was too dark, and the pagan god was inappropriate in a biblical subject. Both details were corrected in a version in tapestry, though the sphinx survived.[44] Poussin's treatments show awareness of much of the scholarly interest in Moses in terms of what we now call comparative religion.[45]

Thereafter attempts at an authentic Egyptian setting were spasmodic, until the start of the 19th century, with the advent of modern Egyptology, and in art the development of Orientalism. By the late 19th-century exotic decor was often dominant, and several depictions concentrated on the ladies of the court, naked but for carefully researched jewellery. The reed beds in the Bible are often given prominence.[46] The extensive history of the scene in the cinema began in 1905, the year after Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema finished his painting, with the Finding the opening scene in a 5-minute biographical film by the French company Pathé.[47]

- Orientalist depictions

Frederick Goodall, 1885

Frederick Goodall, 1885 Edwin Long, 1886

Edwin Long, 1886 James Tissot, 1896–1902, gouache

James Tissot, 1896–1902, gouache

A painting by Paul Delaroche, before 1857, was much reproduced in prints and book illustrations

A painting by Paul Delaroche, before 1857, was much reproduced in prints and book illustrations

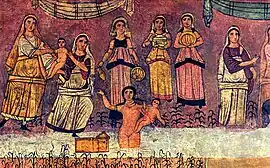

Jewish art and traditions

The earliest visual depiction of the Finding is a fresco in the Dura-Europos synagogue, datable to around 244, a unique large-scale survival of what may have been a large body of figurative Jewish religious art in the Hellenized Roman imperial period.[48] This part of a composite image shows several episodes from the childhood of Moses (only the left end illustrated here) and displays both Midrashic details in the narrative and visual borrowings from the iconography of classical paganism.[49] Six of the 26 frescos in the synagogue have Moses as their main subject.[50] There are a few illustrations in much later medieval Jewish illuminated manuscripts, mostly of the Haggadah, some of which seem to share an iconographical tradition going back to Late Antiquity.[51]

Jewish textual traditions elaborate on the text in Exodus in various ways, and it has been argued that some of these details can be detected in Christian as well as Jewish art. One Jewish tradition was that Pharaoh's daughter, identified as Bithiah, was a leper, who was bathing in the river to cleanse herself, seen as a ritual purification for which she would be naked. As at Dura-Europos, Jewish depictions often include her, and sometimes other women, standing naked in the river.[52] According to Rabbinic tradition, as soon as the princess touched the ark carrying Moses she was healed.[53]

The earliest surviving Christian depiction is a fresco of the 4th century in the Catacomb of Via Latina, Rome. Four figures are on the bank, with Moses still in the water; the largest is the princess, who stretches out her arms, which the baby also does. This gesture may derive from a textual variation found in Midrashic sources and the Aramaic translation of the Bible. In these "she ... sent her female slave" is changed to "she stretched out her arm".[54] Though the context is Christian, many of the images here are of Old Testament subjects,[55] and very likely reflect models adopted from an initially Jewish visual tradition, perhaps painted by artisans with sets of models for all religious requirements. In the play Exagōgē by Ezekiel the Tragedian (3rd century BC), Moses recounts his finding, saying of the princess "And straightway seeing me, she took me up", which may be reflected both in the New Testament Acts 7:20, and in artistic depictions where the princess is apparently first to grasp the ark.[56]

The motif of the naked princess standing in the water, sometimes accompanied by naked maids, reappears in Jewish manuscript illuminations from Spanish workshops in the late Middle Ages, along with some other details of iconography found in the Dura-Europos synagogue.[57] In the 14th-century Golden Haggadah there are three, while Moses' sister Miriam sits on the bank watching them.[58] Other works include the so-called "Sister of the Golden Haggadah" manuscript, and the (Christian) Pamplona Bibles.[59] By contrast, the 18th-century Venice Haggadah has been influenced by local Christian depictions, and shows a clothed princess on land.[60]

A different tradition is first found in Josephus, who was read by Poussin and influenced his treatment of this and other biblical scenes. His account of the finding has the princess "playing by the river bank" and spotting Moses being "borne down the stream". She "sent off some swimmers" to fetch him. Thus in Poussin's 1638 Finding in the Louvre a burly male emerges from the water with the child and basket, a detail sometimes copied by other painters.[61] This is followed in Sebastian Bourdon's painting of 1650, with two male swimmers.[62] Italian paintings more often show female swimmers, or at least females who have landed and are drying themselves after handing the baby to the princess, as in Sebastiano Ricci, Salvator Rosa, Giovanni Francesco Romanelli, as well as a painting in the Rijksmuseum by Paulus Bor and Cornelis Hendriksz Vroom from the 1630s, and Poussin's 1651 composition. The only painting of the subject from Rembrandt's studio shows several naked women who have apparently just come out of the water, bringing the basket.[63]

Islamic art

There is an unusual depiction in the Edinburgh University Library manuscript of the Jami' al-tawarikh, an ambitious world history written in Persia at the start of the 14th century. In the Qur'an and Islamic tradition, it is Pharaoh's wife, Asiya, who rescues the baby, not his daughter. Here the baby Moses remains in his "ark", which is carried along a river with curling Chinese-style waves towards the women.[64]

The queen is in the river with an attendant, both at least clothed in undergarments (more clothes seem to be hanging from a tree branch), and an older servant, or Moses' mother, on the bank. The ark appears enclosed and solid; it looks rather like an elongated coffin, perhaps because the artist was unfamiliar with the subject. There are few comparable Islamic world histories, and like other scenes in the Jami' al-tawarikh, this may be all but unique in Islamic miniatures. The composition may be derived from Byzantine depictions.[65]

This manuscript has seven miniatures of the life of Moses, an unprecedented number perhaps suggesting a special identification with Moses by the author Rashid-al-Din Hamadani, a convert from Judaism who became chief minister of Persia.[66]

Leading depictions

- The Finding of Moses by Gianbattista Tiepolo, in Edinburgh; a different composition in Melbourne.

- The Finding of Moses by Orazio Gentileschi, versions in the Prado, Madrid and National Gallery, London

- The Finding of Moses by Nicolas Poussin; there are three different compositions, two in the Louvre, Paris, the other National Gallery, London

- The Finding of Moses by Paolo Veronese, various compositions, in the Prado, Dresden, Dijon and elsewhere

- The Finding of Moses by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1904, sold at auction in 2010 for nearly US$36 million. Private collection.

Comparative

Zalpuwa is the setting for an ancient legend about the Queen of Kanesh, which was either composed in or translated into the Hittite language:[67]

"[The Queen] of Kanesh once bore thirty sons in a single year. She said: 'What a horde is this which I have born[e]!' She caulked(?) baskets with fat, put her sons in them, and launched them in the river. The river carried them down to the sea at the land of Zalpuwa. Then the gods took them up out of the sea and reared them. When some years had passed, the queen again gave birth, this time to thirty daughters. This time she herself reared them."

See also

- "The Finding of Moses" (poem), a poem by the Irish street poet Zozimus (b. circa 1794 – d. 1846)

Notes

- ↑ This is rarely used in English, but standard in the Latin languages, eg Moïse sauvé des eaux is the normal title in French.

- ↑ Exodus 2, New International Version (NIV); Yavneh, 53–56, analyses the passage and later interpretations of it at length.

- ↑ Wine, 370–371, on the London Poussin; Yavneh, 61, on the Prado Veronese, both disagreeing with other art historians on who figures represent in particular depictions.

- ↑ Note to text as quoted above

- 1 2 Hall, 213

- ↑ Natif, 18, for Byzantine and Islamic examples

- ↑ Again, a rare title in English, but normal in the Latin languages. Nicolas Poussin painted both scenes more than once, and his compositions are described in Blunt, Anthony, "Poussin Studies IV: Two Rediscovered Late Works", The Burlington Magazine, vol. 92, no. 563, 1950, pp. 39–52., JSTOR

- ↑ Ulmer, 297

- ↑ Hand p.80; Purtle, 1999, pp 5–6

- ↑ Schiller, 50 quoted; Wine, 374, note 31

- ↑ Hall, 213; Wine, 369

- ↑ Yavneh, 60; Sistine, 51

- ↑ Hall, 213; Sistine, 52–56

- ↑ Sistine, 43; Hall, 213–216 lists 13 potential scenes.

- ↑ Sistine, 40–41, 50–75 analyze the paired cycles.

- ↑ "WI-ID Subject Tree". iconographic.warburg.sas.ac.uk.

- ↑ One of the single sheets now in the Morgan Library, MS M.0724r.

- ↑ Mann, 169–170

- ↑ Barmash, Pamela, 2, in Exodus in the Jewish Experience: Echoes and Reverberations, Editors, Pamela Barmash, W. David Nelson, 2015, Lexington Books, ISBN 1498502938, 9781498502931, google books; for Poussin's hippo-hunt see below

- ↑ Sistine, 43, 46–47, 51

- ↑ Yavneh, 51; Robertson, 100

- ↑ 'Paul, Benjamin (2012). Nuns and Reform Art in Early Modern Venice: The Architecture of Santi Cosma e Damiano. Ashgate Publishing. p. 244. ISBN 9781409411864.

- ↑ Yavneh, 53, 58–59

- ↑ Bowers, 7–10; both still belong to the London Foundling Hospital; the Hogarth image

- ↑ "Web Gallery of Art, searchable fine arts image database". www.wga.hu.

- ↑ Wine, 366, 369

- ↑ Poussin's various compositions are described in Blunt, Anthony, "Poussin Studies IV: Two Rediscovered Late Works", The Burlington Magazine, vol. 92, no. 563, 1950, pp. 39–52., JSTOR

- ↑ Wine, 374, note 29

- ↑ DeWitt

- ↑ Acts 7:22; Welu, James. "Vermeer's Astronomer: Observations on an Open Book", 266, The Art Bulletin, vol. 68, no. 2, 1986, pp. 263–267., JSTOR

- ↑ "The finding of Moses: Moses brought before Pharoah's daughter by Bonifazio de' Pitati". www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au.

- ↑ Freedberg, 535–536

- ↑ Huse, Norbert; Wolters, Wolfgang (1993-10-30). The Art of Renaissance Venice: Architecture, Sculpture, and Painting, 1460–1590. University of Chicago Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0226361093.

- ↑ Willis, note 7, lists 4, plus 3 from his workshop; Yavneh, 51–53; Robertson, 100

- ↑ Yavneh, 51

- ↑ Willis, quoted; Robertson, 99–100; The Finding of Moses, after 1740, Probably by Francesco Zugno National Gallery

- ↑ Brigstocke, 160; Robertson, 100; the Dresden Veronese

- ↑ Willis

- ↑ Altogether he painted about 19 works set in Egypt, some 10% of his output

- ↑ Wine, 369–370

- ↑ Wine, 369, 374–375, notes 32, 37, 39

- ↑ Bull, 540–541

- ↑ Jaffé, David, "Two Bronzes in Poussin's Studies of Antiquities", in The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal: Volume 17, 1989, 45–46, note 18, 1990, Getty Publications, ISBN 0892361573, 9780892361571, google books

- ↑ Tapestry in the Baroque: New Aspects of Production and Patronage, Metropolitan Museum of Art symposia, Editors Thomas Patrick Campbell, Elizabeth A. H. Cleland, 96, 2010, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 030015514X, 9780300155143, google books

- ↑ Bull, throughout; Wine, 369

- ↑ Thompson, Jason, Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology 1: From Antiquity to 1881, 255, 2015, The American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 9774165993, 9789774165993, google books

- ↑ Tollerton, David, ed., Biblical Reception, 4: A New Hollywood Moses: On the Spectacle and Reception of Exodus: Gods and Kings, 75–77, 2016, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016, ISBN 0567672336, 9780567672339, google books

- ↑ Langston, 47

- ↑ Weitzmann, 366–369, 374; Ulmer, 298–304; Mann, 169–170; Langston, 47

- ↑ Ulmer, 299

- ↑ Mann, 169–172, 183; Ulner, 297 and throughout. For a sceptical view of the links, see Guttmann, 25–26

- ↑ Ulmer, 305

- ↑ Ulner, 311

- ↑ Ulmer, 305; AGK Images

- ↑ "Alcestis and Hercules in the Catacomb of via Latina", Beverly Berg, Vigiliae Christianae, Vol. 48, No. 3 (Sep., 1994), pp. 219–234, Brill, DOI: 10.2307/1584095, JSTOR

- ↑ Ulmer, 304–305

- ↑ Mann, 169–172, 183; Ulmer, 303 has a list in note 26.

- ↑ Ulmer, 307; f. 9r, British Library, MS add. 27210, image

- ↑ Mann, 170; Ulmer's list, 303, note 26

- ↑ Ulner, 322

- ↑ Ulner, 312–314

- ↑ Ulmer, 215

- ↑ DeWitt, fig. 2 and text

- ↑ Natif, 17–18; "The infant Musa (Moses) found by women of Pharaoh's household", Edinburgh University

- ↑ Natif, 17–18

- ↑ Natif, 15

- ↑ Leick, Gwendolyn. A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology. Routledge. 1998. p. 142. ISBN 9780415198110

References

- Bowers, Toni, The Politics of Motherhood: British Writing and Culture, 1680–1760, 1996, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521551749, 9780521551748, google books

- Brigstocke, Hugh; Italian and Spanish Paintings in the National Gallery of Scotland, 2nd Edn, 1993, National Galleries of Scotland, ISBN 0903598221

- Freedberg, Sydney J. Painting in Italy, 1500–1600, 3rd edn. 1993, Yale, ISBN 0300055870

- Bull, Malcolm. "Notes on Poussin's Egypt", The Burlington Magazine, vol. 141, no. 1158, 1999, pp. 537–541., JSTOR

- DeWitt, Lloyd. "Finding of Moses, (PG-100)", in The Leiden Collection Catalogue, Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Ed., New York, 2017, web page: Finding of Moses, by Pieter de Grebber, Leiden

- Gutmann, Joseph, The Dura Europos Synagogue Paintings and Their Influence on Later Christian and Jewish Art, Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 9, No. 17 (1988), pp. 25–29, JSTOR, or Free online

- Hand, J.O., & Wolff, M., Early Netherlandish Painting (catalogue), National Gallery of Art, Washington/Cambridge UP, 1986, ISBN 0-521-34016-0. Entry pp. 75–86, by Hand.

- Hall, James, Hall's Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, 1996 (2nd edn.), John Murray, ISBN 0719541476

- Langston, Scott M., Exodus Through the Centuries, 2013, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 111871377X, 9781118713778, google books

- Mann, Vivian B., "Observations on the Biblical Miniatures in Spanish Haggadot", in Exodus in the Jewish Experience: Echoes and Reverberations, Editors, Pamela Barmash, W. David Nelson, 2015, Lexington Books, ISBN 1498502938, 9781498502931, google books

- Natif, Mikah, "Rashid al-Din’s Alter Ego: The Seven Paintings of Moses in the Jami al-Tawarikh", in Rashid al-Din. Agent and Mediator of Cultural Exchanges in Ilkhanid Iran, 2013, online text, academia.edu

- Purtle, Carol J, The Art Bulletin, March 1999, "Van Eyck's Washington 'Annunciation': narrative time and metaphoric tradition", Vol. 81, No. 1 (Mar., 1999), pp. 117–125. Page references are to online version, no longer available (was here), JSTOR

- Robertson, Giles. "Tiepolo's and Veronese's Finding of Moses", The Burlington Magazine, vol. 91, no. 553, 1949, pp. 99–101., JSTOR

- Schiller, Gertrude Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I,1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, pp 33–52 & figs 66–124, ISBN 0-85331-270-2

- "Sistine": Pietrangeli, Carlo, et al., The Sistine Chapel: The Art, the History, and the Restoration, 1986, Harmony Books/Nippon Television, ISBN 0-517-56274-X

- Ulmer, Rivka, Egyptian Cultural Icons in Midrash, Chapter 10, "The Finding of Moses in Art and Text", 2009, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3110223929, 9783110223927, google books

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 149, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790; full text available online from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Willis, Zoe, "The Melbourne Finding of Moses: Steps towards a New Attribution", 2008 Art Bulletin of Victoria, No. 48, National Gallery of Victoria (by 2017 this painting was attributed to Tiepolo)

- Wine, Humphrey, National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The Seventeenth Century French Paintings, 2001, National Gallery Publications Ltd, ISBN 185709283X

- Yavneh, Naomi, "Lost and Found; Veronese's Finding of Moses", Chapter 3 in Gender and Early Modern Constructions of Childhood, 2016, Eds. Naomi J. Miller, Naomi Yavneh, Routledge, ISBN 1351934848, 9781351934848, google books and google books – ebook, with different pages viewable

External links

Media related to Finding of Moses at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Finding of Moses at Wikimedia Commons