Imperial Abbey of Essen Stift Essen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 845–1803 | |||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||

| Status | Imperial Abbey of the Holy Roman Empire | ||||||

| Capital | Essen Abbey | ||||||

| Government | Theocracy | ||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||

• Founded | circa 845 | ||||||

• Gained Imperial immediacy | between 874 and 947 circa 845 | ||||||

• Gained princely status | 1228 | ||||||

1495 | |||||||

• Joined Westphalian Circle | 1512 | ||||||

• Occupied by the Kingdom of Prussia | 1802 | ||||||

• Annexed by Prussia | 1803–06/7 and from 1813 1803 | ||||||

• Awarded to Berg | 1806/7—1813 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | Germany | ||||||

Essen Abbey (Stift Essen) was a community of secular canonesses for women of high nobility that formed the nucleus of modern-day Essen, Germany.

A chapter of male priests were also attached to the abbey, under a dean. In the medieval period, the abbess exercised the functions of a bishop, except for the sacramental ones, and those of a ruler, over the very extensive estates of the abbey, and had no clerical superior except the pope.[1]

History

It was founded about 845 by the Saxon Altfrid (died 874), later Bishop of Hildesheim and saint, near a royal estate called Astnidhi, which later gave its name to the religious house and to the town. The first abbess was Altfrid's kinswoman, Gerswit. Altfrid also built a church for the canonesses, the Stiftskirche, later known as the Essener Münster and from 1958 as Essen Cathedral. Only women from the highest circles of German nobility were accepted.[2]

Because of its advancement by the Liudolfings (the family of the Ottonian Emperors) the abbey became reichsunmittelbar (an Imperial abbey) sometime between 874 and 947. Apart from the abbess, the canonesses did not take vows of perpetual celibacy; they lived in some comfort in their own houses, with their own staff, and wore secular clothing except when performing clerical roles such as singing the Divine Office. They could travel, and leave the abbey at any time to marry.[2]

Its best years began in 973 under the Abbess Mathilde, granddaughter of Otto I and thus herself a Liudolfing, who governed the abbey until 1011. In her time the most important of the art treasures of what is now the Essen Cathedral treasury came to Essen.[3] She acquired from Koblenz the relics of (Florinus of Remüs) for the abbey,[4] and donated the processional Cross of Otto and Mathilde.

The next two abbesses to succeed her were also from the Liudolfing family and were thus able further to increase the wealth and power of the foundation. In 1228 the abbesses were designated "Princesses" for the first time. From 1300 they took up residence in Schloss Borbeck, where they spent increasing amounts of time. In wartime it was also a refuge for common people.[2]

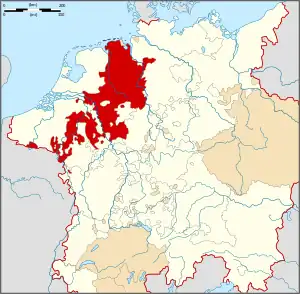

The abbey's territorial lordship, to which belonged the town of Essen that was centered on the monastery, grew up between the Emscher and the Ruhr, The town's efforts to become an independent Imperial city were frustrated by the abbey in 1399 and again, conclusively, in 1670. In the north of the territory was located the abbey's monastery of Stoppenberg, founded in 1073; to the south was the collegiate foundation of Rellinghausen. Also among the possessions of the abbey was the area round Huckarde, on the borders of the County of Dortmund and separated from the territory of Essen by the County of the Mark. Approximately 3,000 farms in the area owed dues to the abbey, in Vest Recklinghausen, on the Hellweg and round Breisig and Godesberg. From 1512 to its dissolution the Imperial abbey belonged to the Lower Rhenish-Westphalian Circle.

The abbey's Vögte were, in sequence:

- the Counts of Berg

- the Counts of the Mark (1288)

- the Dukes of Cleves

- the Dukes of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

- the Margraves of Brandenburg (from 1609/48)

In 1495 the abbey signed a contract with the Dukes of Cleves and Mark regarding the inheritance of the Vogtei, whereby it lost some of its political independence in that it was no longer able to choose its own Vogt.

The princess Abbess Franziska Christine founded an orphanage for the Essen Abbey Region near Steele.

From 1802 the territory was occupied by Prussian troops. The abbey was dissolved in 1803. The spiritual territory of 8 square kilometres (3 square miles) passed to Prussia, then between 1806/1807 to 1813 to the Duchy of Berg and afterwards to Prussia again. The last abbess, Maria Kunigunde von Sachsen, died on 8 April 1826 in Dresden.

When in 1958 the Diocese of Essen was created, the former abbey church became Essen Cathedral, to which the abbey's treasury (Essener Domschatz), including the famous Golden Madonna of Essen, also passed.[3]

List of the Abbesses, later Princess-Abbesses, of Essen

The dates of the rule of the abbesses are incompletely preserved. The sequence of the abbesses between Gerswid II and Ida is uncertain, particularly in regard to the Abbess Agana.

- Gerswid I (about 850; relative of Saint Altfrid)

- Gerswid II (about 880)

- Adalwi (d. 895(?))

- Wicburg (about 896–906)

- Mathilde I (907–910)

- Hadwig I (910–951) – it was probably under her that the abbey became reichsunmittelbar

- Agana (951–965)

- Ida (966–971)

- Mathilde II (971–1011; granddaughter of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor)

- Sophia (1012–1039; daughter of Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor; Abbess of Gandersheim Abbey from 1001)

- Theophanu (1039–1058; granddaughter of Otto II)

- Svanhild (1058–1085) (de) – founded Stoppenberg Abbey

- Lutgarde (about 1088–1118)

- Oda (of Calw?) (1119–1137)

- Ermentrude (about 1140–after 1154)

- Hedwig von Wied (1154–about 1172; Abbess of Gerresheim Abbey)

- Elisabeth I (1172–before 1216; Abbess of St. Maria im Kapitol (Cologne) and of Vreden Abbey)

- Adelheid (1216–1237)

- Elisabeth II (c. 1237–1241)

- Bertha of Arnsberg (before 1243–1292)

- Beatrix of Holte (1292–1327)

- Kunigunde of Berg (1327–resigned 1337, died 1355; Abbess of Gerresheim)

- Katharina of the Mark (1337–1360)

- Irmgard of Broich (1360–1370)

- Elisabeth III of Nassau (1370–resigned nk; d. 1412)

- Margarete I of the Mark-(Arensberg) (1413–resigned 1426; d. 1429)

- Elisabeth IV Stecke von Beeck (1426–1445)

- Sophia I von Daun-Oberstein (1445–1447)

- Elisabeth V von Saffenberg (1447–1459)

- Sophia II von Gleichen, sister of the Abbot of Werden (1459–1489)

- Meina von Daun-Oberstein (1489–resigned 1521; d. 1525)

- Margarete II von Beichlingen (1521–1534) (Abbess of Vreden)

- Sibylle von Montfort (1534–1551)

- Katharina von Tecklenburg (1551–1560)

- Maria von Spiegelberg (1560–1561)

- Irmgard von Diepholz (1561–1575)

- Elisabeth VI von Manderscheid-Blankenheim-Gerolstein (1575–resigned 1578 and married)

- Elisabeth VII von Sayn (1578–1588) (Abbess of Nottuln Abbey)

- Elisabeth VIII von Manderscheid-Blankenheim (1588–1598)

- Margarete Elisabeth von Manderscheid-Blankenheim (1598–1604; Abbess of Gerresheim, Schwarzrheindorf and Freckenhorst)

- Elisabeth IX von Bergh-s’Heerenberg (1604–1614; Abbess of Freckenhorst and Nottuln)

- Maria Clara von Spaur, Pflaum und Vallier (1614–1644; Abbess of Nottuln and Metelen Abbeys)

- Anna Eleonore von Stauffen (1644–1645; Abbess of Thorn Abbey)

- Anna Salome von Salm-Reifferscheid (1646–1688)

- vacant: Regency of the General Chapter (1688–1690)

- Anna Salome of Manderscheid-Blankenheim (1690–1691; Abbess of Thorn)

- Bernhardine Sophia of East Frisia and Rietberg (1691–1726)

- Francisca Christina of Pfalz-Sulzbach (1726–1776; Abbess of Thorn)[5]

- Maria Kunigunde of Saxony (1776–resigned 1802; d. 1826; Abbess of Thorn)

Burials

- Saint Altfrid

References

- ↑ Kahnitz, 123-127

- 1 2 3 "Power in the hands of Women Princess-Abbesses rule Essen", Landschaftsverbände Westfalen-Lippe

- 1 2 "The Treasury of Essen Cathedral", UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- ↑ Röckelein, Der Kult des heiligen Florinus in Essen, p. 84.

- ↑ [ Ute Küppers-Braun: Frauen des hohen Adels im kaiserlich-freiweltlichen Damenstift Essen (1605–1803), Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Münster 1997, p. 155 ISBN 3-402-06247-X

Bibliography

- Ute Küppers-Braun: Macht in Frauenhand – 1000 Jahre Herrschaft adeliger Frauen in Essen. Essen 2002.

- Torsten Fremer: Äbtissin Theophanu und das Stift Essen. Verlag Pomp, 2002, ISBN 3-89355-233-2.

- Kahnitz, Rainer, "The Gospel book of Abbess Svanhild of Essen in the John Rylands Library, I", 1971, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, John Rylands University Library, Manchester, ISSN 0301-102X, PDF online

External links

- (in German) Frauenstift Essen

- (in German) Historischer Verein für Stadt und Stift Essen e.V.

- (in German) Familienforschung in den Kirchenbüchern des Stifts Essen