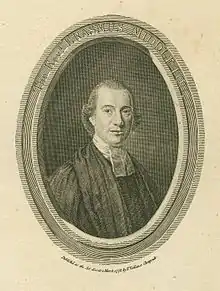

Erasmus Middleton (1739–1805) was an English clergyman, author and editor.

Early life

He was the son of Erasmus Middleton of Horncastle, Lincolnshire. At age 22 he underwent a religion conversion among Wesleyan Methodists in Horncastle. He was then sent to Joseph Townsend in Pewsey for tuition.[1]

Expulsion from Oxford

Middleton entered Clare College, Cambridge as a sizar in 1765.[2] On 4 June 1767 he matriculated at St Edmund Hall, Oxford, but was expelled from the university in May 1768, along with five other members of the Hall, for publicly praying and preaching. The group were known as the "preaching tradesmen". At the time it was said that Selina, Countess of Huntingdon had sponsored them; in the case of two of the students, at least, there was a definite connection.[3][4] The Hall in the middle of the 18th century had only around a dozen students. Its tolerant Principal George Dixon had tried to raise numbers, and had no part in the expulsions, though he did not share the Calvinist tone of the beliefs of the group.[5]

At this time the leader of the few evangelicals at Oxford was James Stillingfleet (1752–1768), a Fellow of Merton College. The group of Oxford Methodists met in a private home, led by him; there were five more students, with the six who were expelled. John Higson of St Edmund Hall complained to David Durell, who was then vice-chancellor.[6][7]

The affair caused a furore, and some pamphleteering.[4] One of the charges against Middleton individually was that he had officiated at a service in the chapel of ease at Chieveley, though a layman.[8] The six students were defended by Sir Richard Hill, 2nd Baronet.[9] In turn Thomas Nowell defended the university's actions, leading to further polemical exchanges.[10] One of Nowell's claims was that Middleton's acquaintance with Thomas Haweis was supposed to be enough to get him holy orders, refused by the Bishop of Hereford (Lord James Beauclerk) on the grounds of insufficient learning, through unspecified influence. The Chieveley incident was reported to date to three years earlier.[11] Two further prominent defenders of the students were George Whitefield and "The Shaver", the pseudonym of the Baptist minister John Macgowan, who waxed satirical against the academics.[12] Samuel Johnson pronounced his approval of the expulsions.[5]

The matter was still a live one in 1806, after Middleton's death, with George Croft raking it up in the Anti-Jacobin Review. He traced some of the later history of Benjamin Kay, Thomas Jones and Thomas Grove (by then nonconformist minister settled at Walsall), three of the other students involved. He awarded George Dixon "indelible infamy", and said Middleton's edition of Leighton's works was "illiterate".[13] Jones had studied with John Newton before going to Oxford, and after being ordained became curate of Clifton, Bedfordshire.[14]

Clerical career

Middleton, nevertheless, had financial backing, from the banker William Fuller. He is said to have graduated B.D. at King's College, Cambridge in 1769 (doubted in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography).[15] He also obtained ordination, from James Traill, the bishop of Down and Connor.[16] He much later entered King's College, Cambridge, in 1783, as a fellow-commoner; but apparently did not graduate.[2]

Middleton became minister at Dalkeith.[4] In 1770 he associated with Willielma Campbell, Lady Glenorchy, and was asked to be the opening preacher at her new chapel, St Mary's Chapel in Niddry's Wynd, Edinburgh.[17] Her plans to bring another of the expelled students, Thomas Grove, to one of her Scottish chapels as resident preacher, were later blocked in 1776 by the Church of Scotland.[18]

Subsequently Middleton had a succession of positions in London, where he was curate to William Romaine.[19][20] In 1775 he was lecturer of St Leonard Eastcheap.[21] He was lecturer at St Luke's, Chelsea, and curate from 1787, under William Bromley Cadogan, who was rector there from 1775 to 1797.[19][22][23] He was lecturer of St. Benet, Gracechurch Street and St. Helen, Bishopsgate, and curate of St. Margaret's Chapel, Westminster.[4] He was also chaplain to the Countess of Crawford and Lindsay.[4]

The Protestant Association

During the late 1770s, Middleton was a close supporter of Lord George Gordon and the Protestant Association.[24] He has been credited with being the Association's founder.[25] At Gordon's trial, Middleton was a principal defence witness, and detailed the setting up of the Association, up to the date 12 November 1779, when Gordon took it over as President.[26]

On Middleton's account the Association was formed in 1778.[27] The early London meetings in Coachmakers' Hall in imitation of the Scottish Protestant Association were open to all Protestants. They were procedurally lax but required civility, concentrated on opposition to Popery, and were made fun of by George Kearsley.[28] On the issue of the petition to parliament, the direct cause of the Gordon Riots of June 1780, Middleton's evidence was that he was Gordon's sole supporter on the Association's committee for proceeding immediately rather than delaying the presentation.[29]

Last years

In 1804 Middleton was made rector of Turvey, Bedfordshire, through the patronage of the Fuller family.[15] He died on 25 April 1805.[4]

Works

Middleton wrote:[4]

- A Letter to A. D., Esq., (Edinburgh), 1772.

- The theological, philosophical, critical, and poetical parts of a New Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 1778. Also involved in the project, with others, was William Turnbull.[30]

- Biographia Evangelica, or an Historical Account of the Lives and Deaths of the most eminent and evangelical Authors or Preachers both British and Foreign in the several Denominations of Protestants, 4 vols. London, 1779–86.

- Versions and Imitations of the Psalms of David, London, 1806, on the title-page of which he is styled B.D.

Middleton edited The Gospel Magazine as Augustus Montague Toplady's successor, until 1783 when it was replaced by the New Spiritual Magazine.[15] He also published sermons.[4][31] In 1805 appeared his edition of the Works of Robert Leighton, 4 vols.[32] He also published the Commentary on St. Paul's Epistle to the Galatians, by Martin Luther, issued with a Life of Luther, a work edited in 1850 by John Prince Fallowes. This version is based on the English translation of 1575.[33][34] That was a project of John Foxe, printed by Thomas Vautrollier, also issued with a life of Luther which is thought to be by Foxe himself.[35][36]

Notes

- ↑ Erasmus Middleton (1807). Evangelical Biography: Being a Complete and Fruitful Account of the Lives ... & Happy Deaths of Eminent Christians. J. Stratford. p. 370. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- 1 2 "Middleton, Erasmus (MDLN765E)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ John R. Tyson (1 January 2006). In the Midst of Early Methodism: Lady Huntingdon and Her Correspondence. Scarecrow Press. p. 20 note 99. ISBN 978-0-8108-5793-3. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lee, Sidney, ed. (1894). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 37. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- 1 2 H. E. Salter and Mary D. Lobel (editors) (1954). "St. Edmund Hall". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3: The University of Oxford. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Reynolds, J. S. "Walker, Samuel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28510. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Josiah Henry Barr, Early Methodists under Persecution (1916?), pp. 178–80; archive.org.

- ↑ Edwin Sidney (1839). The Life of Sir Richard Hill, Bart., M. P. for the County of Shropshire. R. B. Seeley and W. Burnside; sold by L. and G. Seeley. p. 115. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney, eds. (1891). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 26. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ Lee, Sidney, ed. (1895). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 41. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ Thomas Nowell (1769). An Answer to a Pamphlet: Entitled Pietas Oxoniensis, in a Letter to the Author. Wherein the Grounds of the Expulsion of Six Members from St. Edmund-Hall are Set Forth. at the Clarendon-Press. MDCCLXIX. Sold by Daniel Prince. And by John Rivington, London. p. 25. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Firman, Catharine K. (1960). "A Footnote on Methodism in Oxford". Church History. 29 (2): 161–166. doi:10.2307/3161828. JSTOR 3161828. S2CID 162590570.

- ↑ The Antijacobin Review: And Protestant Advocate: Or, Monthly Political and Literary Censor. Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, Paternoster-Row. 1806. pp. 511–5. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ D. Bruce Hindmarsh (2001). John Newton and the English Evangelical Tradition. W. B. Eerdmans. pp. 157–8. ISBN 0-8028-4741-2.

- 1 2 3 Levin, Adam Jacob. "Middleton, Erasmus". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18671. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Erasmus Middleton (1807). Evangelical Biography: Being a Complete and Fruitful Account of the Lives ... & Happy Deaths of Eminent Christians. J. Stratford. p. 372. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ David Francis Bacon (1833). Memoirs of eminently pious women of Britain and America. D. McLeod. p. 290. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Thomas Snell Jones (1824). The life of ... Willielma, viscountess Glenorchy. p. 350. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- 1 2 The Gospel magazine, and theological review. Ser. 5. Vol. 3, no. 1-July 1874. 1839. p. 126. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Erasmus Middleton (1807). Evangelical Biography: Being a Complete and Fruitful Account of the Lives ... & Happy Deaths of Eminent Christians. J. Stratford. p. 373. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Dr William Gibson; William Gibson (4 January 2002). The Church of England 1688-1832: Unity and Accord. Taylor & Francis. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-203-13462-7. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Isabella Burt (1871). Historical notices of Chelsea, Kensington, Fulham, and Hammersmith: With some particulars of old families. Also an account of their antiquities and present state. J. Saunders. p. 135. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Thomas Faulkner (1829). An historical and topographical description of Chelsea, and its environs: interspersed with biographical anecdotes of illustrious and eminent persons who have resided in Chelsea during the three preceding centuries. Printed for T. Faulkner. pp. 87–. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Ian Haywood; John Seed (1 March 2012). The Gordon Riots: Politics, Culture and Insurrection in Late Eighteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge University Press. p. 49 and p. 78. ISBN 978-0-521-19542-3. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Eugene Charlton Black (1963). The Association: British Extraparliamentary Political Organization, 1769-1793. Harvard University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-674-05000-6. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Edmund Burke (1791). Dodsley's Annual Register. J. Dodsley. p. 231. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Hexter, J. H. (1936). "The Protestant Revival and the Catholic Question in England, 1778-1829". The Journal of Modern History. 8 (3): 297–319. doi:10.1086/468452. JSTOR 1881538. S2CID 153924065.

- ↑ Black, Eugene Charlton (1963). "The Tumultuous Petitioners: The Protestant Association in Scotland, 1778-1780". The Review of Politics. 25 (2): 183–211. doi:10.1017/S003467050000485X. JSTOR 1405622. S2CID 146502784.

- ↑ James Boswell (1781). The Scots Magazine. Sands, Brymer, Murray and Cochran. p. 233. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ Thomas Ellis; Erasmus Middleton; William Turnbull (1778). The New Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences; Or, an Universal System of Useful Knowledge ... The Theological, Philosophical, Critical, and Poetical Branches, by the Rev. Erasmus Middleton ... the Medicinal, Chemical, and Anatomical, by William Turnbull ... the Gardening and Botanical, by Thomas Ellis ... the Mathematical, &c. by John Davison ... and Other Parts by Gentlemen of Approved Abilities in the Respective Branches which They Have Engaged to Illustrate. The Authors. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ John Gadsby (1870). Memoirs of the Principal Hymn-writers: & Compilers of the 17th, 18th, & 19th Centuries. J. Gadsby. p. 62. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ William Thomas Lowndes (1834). The Bibliographer's Manual of English Literature. W. Pickering. p. 1096. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ Camden, Vera J. (1997). "'Most Fit for a Wounded Conscience' The Place of Luther's 'Commentary on Galatians' in Grace Abounding". Renaissance Quarterly. 50 (3): 819–849. doi:10.2307/3039263. JSTOR 3039263. S2CID 163268381.

- ↑ "Renaissance Books". Renaissance Quarterly. 33 (1): 154–173. 1980. JSTOR 2861577.

- ↑ James Joseph Kearney (2009). The Incarnate Text: Imagining the Book in Reformation England. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-8122-4158-7. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ↑ Joseph Kerman (1962). The Elizabethan madrigal: a comparative study. The AMS. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-19-647229-4. UCSC:32106001382743. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1894). "Middleton, Erasmus". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 37. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1894). "Middleton, Erasmus". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 37. London: Smith, Elder & Co.