Equites cataphractarii, or simply cataphractarii, were the most heavily armoured type of Roman cavalry in the Imperial Roman army and Late Roman army. The term derives from a Greek word, κατάφρακτος kataphraktos, meaning "covered over" or "completely covered" (see Cataphract).

Origins

Heavily armoured cataphract cavalry, usually armed with a long lance (contus), were adopted by the Roman army to counter Parthian troops of this kind on the eastern frontier and similar Sarmatian cavalry in on the Danubian frontier.[1] In distinction to both Parthian and Sarmatian cataphracts, who represented a wealthy feudal or tribal elite equipped for war, Roman cataphracts had no social dimension, being composed of professional soldiers like any other troop type of the Roman army. The Romans also used the terms contarii for lance-armed cavalry, and clibanarii for heavily armoured cavalry. It is uncertain whether these terms were used interchangeably with 'cataphract', or whether they implied differences of equipment and role.[2]

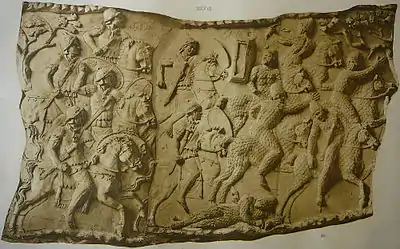

Appearance and equipment

Modelled on the cataphracts of Parthia, they were armoured from neck-to-toe by a variety of armour types, probably including: scale armour (lorica squamata), mail armour (lorica hamata), and laminar armour (see manica). A number of descriptions indicate that helmets with visors shaped like human faces were worn. However, a graffito from the Roman frontier fortress of Dura Europos shows a cataphract wearing a conical helmet with a face-covering mail aventail.[3] They were normally armed with a contus, a long lance held in both hands. However, the name of one unit, equites sagitarii clibanarii, implies that these troops carried bows instead of, or in addition to, the contus. As a secondary weapon they were armed with swords (spathae). In some cases, their horses were covered in scale armour also.[4] Two iron and copper-alloy scale horse armours, usually called 'trappers' or 'bards', still attached to fabric backings were discovered in a 3rd-century context at Dura Europos.[5]

One of the best descriptions of these cavalry to survive, was made by the Late Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus:

“...among these were scattered cavalry with cuirasses (cataphracti equites), whom they call clibanarii, masked, protected by coverings of iron breast-plates, and girdled with belts of iron, so that you would fancy them statues polished by the hand of Praxiteles, rather than men. And the light circular plates of iron which surrounded their bodies, and covered all their limbs, were so well fitted to all their motions, that in whatever direction they had occasion to move, the joints of their iron clothing adapted themselves equally to any position.” Ammianus (16.10.8)

Also the emperor Julian the Apostate made a detailed description:

"Your cavalry was almost unlimited in numbers and they all sat their horses like statues, while their limbs were fitted with armour that followed closely the outline of the human form. It covers the arms from wrist to elbow and thence to the shoulder, while a cuirass made of small pieces protects the shoulders, back and breast. The head and face are covered by a metal mask which makes its wearer look like a glittering statue, for not even the thighs and legs and the very ends of the feet lack this armour. It is attached to the cuirass by fine chain-armour like a web, so that no part of the body is visible and uncovered, for this woven covering protects the hands as well, and is so flexible that the wearers can bend even the fingers." Julian, Orations I, Panegyric of Constantius, 37D (Loeb translation)

Battlefield role and limitations

Heavily armoured, often mounted on armoured horses and wielding a lance so long it normally required both hands, the cataphractarii were specialised for shock action. They have been likened to the tank of the Ancient World. Their armour enabled them to attack enemy infantry and cavalry with confidence and virtually ignore missile fire. However, the armour was heavy and both soldier and mount could tire quickly in battle, and therefore become vulnerable to counterattack. In particular, horse armour prevented the horse from cooling itself effectively by sweating; therefore heat exhaustion could be a great problem, especially in hot climates. Cataphracts needed to maintain a close and ordered formation to be effective and their flanks were particularly vulnerable to attack. If their formation became broken, individual cataphracts could be attacked by lighter-armed troops with relative ease.[6]

At the Battle of Turin the emperor Constantine I destroyed a numerous force of enemy cataphracts; he manoeuvred his army in such a way that his more lightly armoured and mobile cavalry were able to charge in on the exposed flanks of the cataphracts. Constantine's cavalry were equipped with iron-tipped clubs, ideal weapons for dealing with heavily armoured foes.[7]

Development

It was apparently from the time of the emperor Hadrian (r. 117–138 AD) that the first regular formations of Roman cataphractarii appear in the record.[8] However, the description by Josephus of heavily armoured, contus-armed Roman cavalry in 67 AD at the siege of Jotapata, during the reign of Vespasian, suggests that cataphracts may have been adopted by the Romans at an considerably earlier date.[9]

The earliest known unit of equites cataphractarii, recorded in the early 2nd century, is the auxiliary cavalry regiment, Ala I Gallorum et Pannoniorum cataphractaria, stationed in Moesia Inferior. The deployment of this unit on the Danube front, rather than in the East, implies that initially the cataphractarii were aimed at countering the Sarmatian rather than the Parthian threat.[10]

Cataphractarii regiments apparently remained few in number in the army of the Principate (to AD 284). They became more numerous in the Late Roman army, especially in the East. However, a number of the "eastern" units have Gaulish names (including the Biturigenses and Ambianenses), indicating their western origins.[11] Nineteen units are recorded in the Notitia Dignitatum, of which one was an elite schola regiment of imperial horse guards. All but two of the rest belonged to the comitatus (field armies), with a minority rated as elite palatini troops. There was just one regiment of cataphract horse archers.

| Corps | Normal HQ | Name of regiment (* = elite palatini grade) | No. of regiments | No. of effectives** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byzantium | Schola scutariorum clibanariorum*[13] | 1 | 500 | |

| COMITATUS PRAESENTALIS I[14] | Nicaea | Comites clibanarii* Equites cataphractarii Biturigenses# Equites I clibanarii Parthi |

3 | 1,500 |

| COMITATUS PRAESENTALIS II[15] | Adrianopolis | Equites Persae clibanarii* Equites cataphractarii Equites cataphractarii Ambianenses# Equites II clibanarii Parthi |

4 | 2,000 |

| COMITATUS ORIENTIS[16] | Antioch | Comites cataphractarii Bucellarii iuniores Equites promoti clibanarii Equites IV clibanarii Parthi Cuneus equitum II clibanariorum Palmirenorum |

4 | 1,750 |

| COMITATUS THRACIAE[17] | Marcianopolis | Equites cataphractarii Albigenses# | 1 | 500 |

| LIMES THEBAIDOS[18] | Thebes (Egypt) | Ala I Iovia cataphractaria | 1 | 250 |

| LIMES SCYTHAE[19] | Cuneus equitum cataphractariorum | 1 | 250 | |

| TOTAL EAST | 15 (12 ex. #) | 6,750 | ||

| COMITATUS PRAESENTALIS[20] | Milan | Comites Alani* Equites sagitarii clibanarii |

2 | 1,000 |

| COMITATUS AFRICAE[21] | Carthage | Equites clibanarii | 1 | 500 |

| COMITATUS BRITANNIARUM[22] | London | Equites cataphractarii iuniores | 1 | 500 |

| TOTAL WEST | 4 (7 inc. #) | 2,000 |

** Assuming 500 effectives in comitatus units, 250 for limitanei

# Eastern army units with Gaulish - Western - names

See also

Citations

- ↑ Sidnell, p. 143

- ↑ Sidnell, pp. 262-265

- ↑ Sidnell, pp. 269-270

- ↑ Conolly, pp. 258-259

- ↑ Bishop and Coulston, p. 55

- ↑ Sidnell, p. 144

- ↑ Odahl, pp. 102, 317-18.

- ↑ Baumer, p. 263

- ↑ Sidnell, pp. 268-629

- ↑ Sidnell, pp. 262, 268

- ↑ Elton, p, 106

- ↑ Notitia Dignitatum

- ↑ Notitia Oriens.XI

- ↑ Notitia Oriens.V

- ↑ Notitia Oriens.VI

- ↑ Notitia Oriens.VII

- ↑ Notitia Oriens.VIII

- ↑ Notitia Oriens.XXXI

- ↑ Notitia Oriens.XXXIX

- ↑ Notitia Occidens.VI

- ↑ Notitia Occidens.VI

- ↑ Notitia Occidens VI

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Ammianus Marcellinus' works in English at the Tertullian Project with introduction on the manuscripts

- Julian the Apostate Orations 1, panegyric to Constantius in English at the Tertullian Project with introduction on the manuscripts

Secondary sources

- Baumer, C. (2012) The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors, I.B.Tauris, London ISBN 978-1-78076-060-5

- Bishop, M. C. and Coulston, J. C. (1989) Roman Military Equipment, Shire Publications, Aylesbury.

- Connolly, P. (1981) Greece and Rome at War. Macdonald Phoebus, London. ISBN 1-85367-303-X

- Elton, Hugh (1996). Warfare in Roman Europe, AD 350–425. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815241-5.

- Odahl, Charles Matson. Constantine and the Christian Empire. New York: Routledge, 2004. Hardcover ISBN 0-415-17485-6 Paperback ISBN 0-415-38655-1

- Sidnell, P. (2006) Warhorse: Cavalry in Ancient Warfare, Continuum, London.

External links

An image of the graffito from Dura Europos depicting a mounted cataphract can be seen here: