Emily Sartain | |

|---|---|

Naudin Studios, Emily Sartain, ca 1880, Moore College of Art and Design, Philadelphia | |

| Born | March 17, 1841 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | June 17, 1927 (aged 86) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | |

| Known for | Mezzotint engraving, painting, art educator |

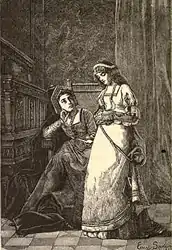

| Notable work | The Reproof |

| Awards |

|

Emily Sartain (March 17, 1841 – June 17, 1927) was an American painter and engraver. She was the first woman in Europe and the United States to practice the art of mezzotint engraving, and the only woman to win a gold medal at the 1876 World Fair in Philadelphia. Sartain became a nationally recognized art educator and was the director of the Philadelphia School of Design for Women from 1866 to 1920.[1] Her father, John Sartain, and three of her brothers, William, Henry and Samuel were artists. Before she entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and studied abroad, her father took her on a Grand Tour of Europe. She helped found the New Century Club for working and professional women, and the professional women's art clubs, The Plastic Club and The Three Arts Club.

Early life

Emily Sartain was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on March 17, 1841.[2] She was the fifth of eight children[3] of Philadelphia master printer and publisher of Sartain's Magazine John Sartain[4] and Susannah Longmate Swaine Sartain.[2]

In 1858, Sartain graduated from the Philadelphia Normal School and then taught school until the summer of 1862.[5] John Sartain taught his daughter art,[2] including the mezzotint engraving technique[5] that he revived, which was a favored process in England that created high-quality prints of paintings.[6] John Sartain believed in equal opportunities for women and encouraged his daughter to pursue a career.[3] He mortgaged his house[5] and gave her a "gentleman's education" in fine art by taking her on a Grand Tour of Europe beginning the summer of 1862.[7] They started in Montreal and Quebec and then sailed for Europe. She enjoyed the English countryside; old world cities, especially Florence and Edinburgh; the Louvre; Italian Renaissance paintings; and artists like Dante and engraver Elena Perfetti.[7] She traveled to Venice to visit William Dean Howells and his wife Elinor Mead Howells, who was a painter. Sartain decided in the course of the trip that she wanted to become an artist.[7] During their travels the Sartains learned that William Sartain had enlisted during the Civil War (1861–1865) and later hastily returned to the United States when John and Emily learned that the Confederate States Army had crossed into Chambersburg, Pennsylvania,[7] which is 158 miles west of Philadelphia.[8]

Of John and Susannah Sartain's children, Samuel (1830–1906), Henry (1833–1895), William Sartain (1843–1925) and Emily[9][10] were painters and engravers,[11] beginning a legacy of Sartain family artists and printmakers.[6] Sartain sought her father's input on her work throughout her career and benefited from his support and connections. She carried on the mezzotint engraving technique that he taught her. Sartain lived with her parents into adulthood,[6][12] supporting and caring for them in their later years. In 1886, her parents moved into her living quarters at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women.[13]

Education

A portrait painter and engraver, Emily Sartain studied with Christian Schussele and her father, John Sartain, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.[14][15] She met Thomas Eakins at the academy[15] and entered into what biographer Henry Adams believes was Eakin's "first known romance". Their romantic relationship ended after Eakins went to Paris to study art and Eakins succumbed to what Sartain described as "temptations of the great city"[16] and due to her interest in women's rights.[17] The two remained lifelong friends.[4]

In 1870, Sartain met Mary Cassatt in Philadelphia and the following year they left for Paris, London, Parma, and Turin to study painting.[18] The women spent the first winter in Italy[10] and studied printmaking with Carlo Raimondi, who taught engraving at the Academy of Fine Arts in Parma.[18] Sartain spent the rest of the four-year stay in Paris[10] and studied under Évariste Vital Luminais.[2] She shared a studio with Jeanne Rongier. Florence Esté, Sartain's friend, also worked in the studio occasionally. The women copied each other's work and provided one another with criticism and encouragement.[19] Two of Sartain's paintings, a genre painting Le Piece de Conviction (The Reproof) and a portrait of Mlle. Del Sarte, were accepted at the Paris salon in 1875.[18][20] Sartain returned to the United States that year,[18][lower-alpha 1] when she ran out of money. Harriet (Hattie) Judd Sartain, who was her brother Samuel's wife and a successful homeopathic physician, had lent Emily Sartain money for her education. Emily believed Hattie was likely to continue to help with education expenses in Philadelphia where expenses were lower and she would more likely sell her works.[22]

Career

Early career

Sartain set up a studio in Philadelphia in 1875 where she created paintings and engravings.[23] Over the course of her career she made copies of paintings in Spanish and Italian galleries, portraits, genre paintings,[20] and was the first woman to practice the art of the mezzotint in the United States and Europe.[2][4][24] Among her works were period scenes that depicted submissive women with downcast eyes as in Italian Woman and The Reproof.[25] Sartain exhibited her works in cities along the East Coast of the United States[13] and was the only woman to win a gold medal at the 1876 World Fair in Philadelphia[4] for The Reproof.[2] She won the Mary Smith Prize for best picture by a woman at the 1881 and 1883 Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts exhibits.[20] Sartain worked as art editor for the paper Our Continent from 1881 to 1883.[2][26] She was then the art editor for New England Bygones (1883) by Ellen C. H. Rollins.[2] Joseph M. Pennell said that Sartain was "the only trained woman art editor I ever knew".[26] Sartain exhibited her work at the Palace of Fine Arts and at the Pennsylvania Building of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois.[27]

Sartain was a progressive New Woman,[25] who with her sister-in-law, Hattie Judd Sartain, formed the woman's organization, the New Century Club. Hattie is believed to have helped her attain the commissions of portraits of local physicians Constantin Hering and James Caleb Jackson.[28] Besides having financed her education and being her ally and mentor, Hattie also modeled for Sartain.[12][lower-alpha 2]

Philadelphia School of Design for Women

In 1886 she became the director of the Philadelphia School of Design for Women,[4] in which her father had served on the board as vice president for years.[29] It was the country's largest art school for women,[31] where she was, according to Henry Adams, "a pioneering advocate of advanced education for women."[32] Sartain implemented life-drawing classes at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women,[33] using draped male and nude women models, which was uncommon for women artists at the time. She created a professional program that was built upon technical and lengthy training and high standards. The women were taught to create works of art based upon three-dimensional and human forms.[29] She trained women who taught art.[31] Through her efforts, she brought the level of instruction at the school to that of a French academy[20] and similar to that of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.[34] Industrial design schools for women were often considered purveyors of lower forms of art, but Sartain believed that good art was defined more by the artist's capabilities than the medium[34] and that the same aesthetic principles used to judge fine art could be applied to commercial art.[20] She was responsible for introducing important faculty members such as Robert Henri, Samuel Murray and Daniel Garber to the school.[35] Sartain was an established, national authority on art education and art for women by 1890.[31][35]

She was an exhibitor, member of the Fine Arts jury,[36] chair of the decorating committee for the Pennsylvania Building,[37] and an art education speaker at the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exposition.[31] In 1897, Emily Sartain and Alice Barber Stephens, a teacher at the school, founded The Plastic Club in Philadelphia.[4][38] She was president of the club from 1899 to 1903 and again in 1904 and 1905.[20] Sartain also help found the Three Arts Club.[34] She spoke in London in 1899 at the Professional Section of the International Congress of Women. In 1900, Sartain attended the first international conference on art education in Paris. She was one of three delegates from the United States[31] that year and again in 1904 in Berne.[2][20] Her article "Value of Training in Design for Woman" was published in 1913 in The New York Times.[39] She led the design school until 1919[35] or 1920.[2][39] Her niece Harriet Sartain led the school after her retirement. Harriet was Henry's daughter[10] and had been mentored by her Aunt Emily.[40] Sartain received certificates, medals, and diplomas in recognition of her service to art and education, including recognition from the London Society of Literature, Science and Art.[2]

Nina de Angeli Walls wrote,

As Sartain's career illustrates, art schools conferred professional status in a cultural field once dominated by men. Women artists used formal schooling to counter the accusation of amateurism frequently leveled at them. Nineteenth century design schools were the first institutions to offer professional certification for women in such careers as art education, fabric design, or magazine illustration; hence, the schools opened unprecedented paths to female economic independence.[31]

Later years

Sartain retired to San Diego, California. During her career Sartain traveled to Europe most summers and continued to travel abroad every year during her retirement. She was visiting in Philadelphia when she died on June 17, 1927.[10][13]

Collections

- Franklin Institute of Science, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Frederick Fraley, ca. 1891–1901, oil[41]

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts:[42]

- Christ Walking on the Sea, Emily Sartain after Henry Richter, 1865, mezzotint, etching and stipple

- Christ Walking on the Water, Emily Sartain after Charles Jalabert, 1867, engraving with roulette

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, Emily Sartain after William Henry Furness, Jr., 1871, mezzotint, etching, engraving and stipple

- Untitled, 1887, oil on wood

- Welcome News, 1888, etching on chine collé

- I. S. Hentchin, etching, engraving, mezzotint, stipple and photomechanical texture

- S. C. Huntington, etching, engraving, mezzotint and stipple

- President Lincoln and Son, mezzotint, etching, engraving, stipple and photomechanical ground

- His Excellency Baron Lisgar, mezzotint, etching, stipple and photomechanical ground

- Samuel Partridge, mezzotint, etching, engraving and stipple

- Alexander Thomson, Emily Sartain after J. C. Darley, etching, engraving, mezzotint and photomechanical ground

- J. W. Weir, Etching, engraving and photomechanical ground

Notes

- ↑ When Sartain returned to the United States, Cassatt remained in Paris.[18] According to Phyllis Peet, Sartain's friendship with Cassatt ended when her friend decided to become an Impressionist.[21]

- ↑ Emily also supported her sister-in-law. She said that Harriet was "one of the most successful physicians in Philadelphia, irrespective of sex," and "was a pioneer among women doctors,—and her personal character is so fine and her scientific acquirements so indisputed, that in the struggle to get women doctors admitted in a different state, county and U.S. Societies, her name was always one selected to make an Entering wedge. The fighting over it could only be on the ground of sex, no other exception could be taken."[29]

References

- ↑ Hoffmann, Mott, Sharon, Amanda (2008). Moore College of Art & Design. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-5659-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 M. Jane Dowd (1978). John F. Ohles (ed.). Biographical Dictionary of American Educators. Vol. 3. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 1148–1149.

- 1 2 Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9. Archived from the original on 2020-02-08. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hoffmann, Mott, Sharon, Amanda (2008). Moore College of Art & Design. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5659-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9.

- 1 2 3 "Mezzotints by John Sartain: Philadelphia Printmaker, 1808–1897 – January 18, 1997 – April 20, 1997". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. pp. 120–123. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9. Archived from the original on 2020-02-08. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- ↑ "Distance between Chambersburg and Philadelphia Pennsylvania". Google maps. Archived from the original on January 23, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "The Sartain family: PAFA's most famous artistic dynasty". Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ann Lee Morgan Former Visiting Assistant Professor University of Illinois at Chicago (27 June 2007). The Oxford Dictionary of American Art and Artists. Oxford University Press. pp. 432–433. ISBN 978-0-19-802955-7. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ↑ Russell T. Clement; Annick Houzé; Christiane Erbolato-Ramsey (2000). "The Women Impressionists: A Sourcebook". Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 37.

- 1 2 Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9. Archived from the original on 2018-08-02. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- 1 2 3 Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9.

- ↑ Russell T. Clement; Annick Houzé; Christiane Erbolato-Ramsey (2000). "The Women Impressionists: A Sourcebook". Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 32.

- 1 2 Ricci, Patricia Likos (2000). "Bella, Cara Emilia: The Italianate Romance of Emily Sartain and Thomas Eakins". In Katherine Martinez and Page Talbott (ed.). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 120–137. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9.

- ↑ Henry Adams (2005). Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 89.

- ↑ Henry Adams (2005). Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 99–100.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Russell T. Clement; Annick Houzé; Christiane Erbolato-Ramsey (2000). "The Women Impressionists: A Sourcebook". Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 23, 24.

- ↑ Kirsten Swinth (2001). Painting Professionals: Women Artists & the Development of Modern American Art, 1870–1930. UNC Press Books. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8078-4971-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Robert McHenry (1980). Famous American Women: A Biographical Dictionary from Colonial Times to the Present. Courier Dover Publications. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-486-24523-2.

- ↑ Phyllis Peet (Spring–Summer 1990). "The Art Education of Emily Sartain". Woman's Art Journal. 11 (1): 9–15. doi:10.2307/1358380. JSTOR 1358380.

- ↑ Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9.

- ↑ Jill P. May; Robert E. May; Howard Pyle (2011). Howard Pyle: Imagining an American School of Art. University of Illinois Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-252-03626-2.

- ↑ Peet, Phyllis (Autumn 1984). "Emily Sartain: America's First Woman Mezzotint Engraver". Imprint. American Historical Print Collectors Society. 9 (2): 19–26. Archived from the original on 2016-08-25. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- 1 2 Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9.

- 1 2 Joseph M. Pennell (1925). The Adventures of An Illustrator: Mostly in Following His Authors in America & Europe. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. p. 102. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ↑ Nichols, K. L. "Women's Art at the World's Columbian Fair & Exposition, Chicago 1893". Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ↑ Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9.

- 1 2 3 Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9.

- ↑ "Study, (painting). Emily Sartain". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nina de Angeli Walls (1998). "Design school movement". In Linda Eisenmann (ed.). Historical Dictionary of Women's Education in the United States. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 129–130. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ↑ Henry Adams (2005). Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 485.

- ↑ Alice A. Carter (2000). The Red Rose Girls: An Uncommon Story of Art and Love. New York: Abrams Books. p. 18. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9.

- 1 2 3 Nina de Angeli Walls (2001). Art, Industry, and Women's Education in Philadelphia. Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 0-89789-745-5.

- ↑ "Philadelphia Letter". The Literary World. S.R. Crocker. 1893. p. 353.

- ↑ Rossiter Johnson (1898). A History of the World's Columbian Exposition Held in Chicago in 1893. D. Appleton. p. 486.

- ↑ Dennis P. Doordan (1995). Design History: An Anthology. MIT Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-262-54076-6.

- 1 2 Sharon G. Hoffman; Amanda M. Mott (2008). Moore College of Art & Design. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-0-7385-5659-8.

- ↑ Katharine Martinez; Page Talbott; Elizabeth Johns (2000). Philadelphia's Cultural Landscape: The Sartain Family Legacy. Temple University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-56639-791-9. Archived from the original on 2016-06-17. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- ↑ "Frederick Fraley, by Emily Sartain". Smithsonian Institution Research Information System. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ↑ "Collection List by Artist: Emily Sartain". Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

Further reading

- Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection (1864). Artists of Abraham Lincoln Portraits: Emily Sartain.

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania. "Sartain Family Papers".

External links

![]() Works related to Woman of the Century/Emily Sartain at Wikisource

Works related to Woman of the Century/Emily Sartain at Wikisource