Edward Burn | |

|---|---|

| Born | 29 November 1762 |

| Died | 20 May 1837 (aged 74) Birmingham |

| Education | Trevecca College |

| Church | Calvinist Methodist |

Congregations served | St Mary's Church |

Edward Burn (1762–1837) was an English cleric, known as a Calvinist Methodist preacher and polemical writer.

Life

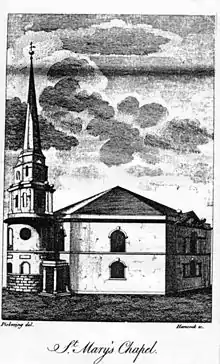

Born on 29 November 1762, Burn was educated for the ministry at Trevecca College. He was ordained orders and obtained a curacy in Birmingham, with John Riland, a Wesleyan and first incumbent at St Mary's Chapel; built 1772–4, it was a new, octagonal evangelical foundation, with Mary Weaman as patron. With Riland, Burn reprinted some religious texts. Burn also began to preach in venues used by dissenters.[1][2][3] In 1786 John Wesley visited St Mary's and enjoyed a sermon, by one of Burn and Riland.[4]

Burn then entered St Edmund Hall, Oxford, and graduated B.A. on 20 February 1790, M.A. on 22 June 1791.[5] He returned to Birmingham to take over at St Mary's.[4] He was known as a preacher for extemporary oratory. He retained this position till his death. He was one of the founders of the Birmingham Association of the Church Missionary Society, and its first secretary. He came to work with Unitarians on the local committee of the Bible Society; and, as he grew older, became a liberal in politics. In 1830 he is mentioned as minister of St James's Chapel, Ashted, Birmingham,[5] Among those touched by his ministry was George Mogridge.[6]

Opponent of Priestley

Burn first published in theological controversy with Joseph Priestley, a fellow Birmingham preacher with whom he was acquainted; he received the thanks of Beilby Porteus.[5] Priestley wrote a frank private letter to Burn in 1790, published in part later, explaining his support for Charles James Fox's legislative moves on religious tolerance, and that the Church of England was storing up trouble for itself.[7] The nickname "Gunpowder Priestley" came from a phrase in it.[8] Edmund Burke picked up on the metaphor, which in fact could be found in other places in Priestley's writings.[9]

Burn became identified with a group of local "Church-and-King" clergy in Birmingham, including George Croft and Spencer Madan, and opponents of Priestley, if not the most extreme.[10] On Priestley's account, he met both Burn and Madan through committee work, and was on reasonable terms with them; even on visiting terms with Burn.[11] A subsequent pamphlet of Burn refers to the Birmingham riots of 14 July 1791, its aftermath, and Priestley's Appeal to the Public of 1792. Burn's later judgement (1820, in conversation with Francis William Pitt Greenwood) was that Priestley had handled him roughly; but in October 1825 he expressed public regret at a dinner for his own asperity.[5][12]

Death

Burn died at Birmingham 20 May 1837; at the time of his death he held, with St Mary's, the rectory of Smethcott in Shropshire. He was followed to the grave by ministers of all persuasions. He married and left children.[5]

Works

Burn published, with sermons and tracts (including a mission sermon in London of 1806):[5]

- The Fact; or instance of demoniacal possession improved, 1788.

- Letters to Dr. Priestley on the Infallibility of the Apostolical Testimony concerning the Person of Christ, 1790, two editions, same year. Replied to by Priestley in Letters to the Rev. E. Burn, 1790.

- Letters to Dr. Priestley, in Vindication, &c., 1790. Replied to by Priestley in Familiar Letters, addressed to the Inhabitants of Birmingham, 1790, letter xviii.

- A Reply to the Rev. Dr. Priestley's Appeal to the Public on the subject of the Riots at Birmingham, 1792. Replied to by John Edwards (1768–1808),[13] Priestley's successor at the New Meeting House, in Letters to the British Nation, part iv. [1792], and by Priestley in Appeal, part ii, 1792.

- Pastoral Hints or the Importance of a Religious Education, 1801.

- Serious Hints &c. to the Clergy at this momentous crisis, Birmingham, 1798, (sermon on Is. i. 9, before the university of Oxford, 4 February 1798).

Notes

- ↑ John Money (1977). Experience and Identity: Birmingham and the West Midlands, 1760-1800. Manchester University Press. pp. 215 note 30. ISBN 978-0-7190-0672-2.

- ↑ Paul Wood (2004). Science and Dissent in England, 1688-1945. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7546-3718-9.

- ↑ The Picture of Birmingham. Drake. 1831. p. 50.

- 1 2 W.B. Stephens, ed. (1964). "Religious History: Churches built before 1800". A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 7: The City of Birmingham. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1886). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 7. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ Charles Williams (1856). George Mogridge: His Life, Character, and Writings. Ward and Lock. p. 137.

- ↑ Jack Fruchtman (1 January 1983). The Apocalyptic Politics of Richard Price and Joseph Priestley: A Study in Late Eighteenth Century English Republican Millennialism. American Philosophical Society. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-87169-734-9.

- ↑ John Ashton Cannon (2009). A Dictionary of British History. Oxford University Press. p. 1146. ISBN 978-0-19-955038-8.

- ↑ Regina Hewitt; Pat Rogers (2002). Orthodoxy and Heresy in Eighteenth-century Society: Essays from the DeBartolo Conference. Bucknell University Press. pp. 55 and 66 note 14. ISBN 978-0-8387-5501-3.

- ↑ John Alfred Langford (1868). A Century of Birmingham life, or, A chronicle of local events, from 1741 to 1841. E. C. Osborne. p. 13.

- ↑ John Corry (1804). The Life of Joseph Priestley. p. 101.

- ↑ Robert E. Schofield (2004). The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773 to 1804. Penn State Press. p. 272 note 25. ISBN 978-0-271-04624-2.

- ↑ Lord Byron and His Times, Henry Roscoe The Life of William Roscoe, John Edwards (1768–1808).

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1886). "Burn, Edward". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 7. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1886). "Burn, Edward". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 7. London: Smith, Elder & Co.