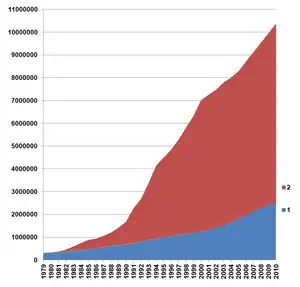

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 314,100 | — |

| 1980 | 332,900 | +6.0% |

| 1981 | 366,900 | +10.2% |

| 1982 | 449,500 | +22.5% |

| 1983 | 595,200 | +32.4% |

| 1984 | 741,300 | +24.5% |

| 1985 | 881,500 | +18.9% |

| 1986 | 935,600 | +6.1% |

| 1987 | 1,054,400 | +12.7% |

| 1988 | 1,201,400 | +13.9% |

| 1989 | 1,416,000 | +17.9% |

| 1990 | 1,677,800 | +18.5% |

| 1991 | 2,267,600 | +35.2% |

| 1992 | 2,680,200 | +18.2% |

| 1993 | 3,359,700 | +25.4% |

| 1994 | 4,127,100 | +22.8% |

| 1995 | 4,491,500 | +8.8% |

| 1996 | 4,828,900 | +7.5% |

| 1997 | 5,277,500 | +9.3% |

| 1998 | 5,803,300 | +10.0% |

| 1999 | 6,325,600 | +9.0% |

| 2000 | 7,012,400 | +10.9% |

| 2001 | 7,245,700 | +3.3% |

| 2002 | 7,466,200 | +3.0% |

| 2003 | 7,782,700 | +4.2% |

| 2004 | 8,008,000 | +2.9% |

| 2005 | 8,277,500 | +3.4% |

| 2006 | 8,711,000 | +5.2% |

| 2007 | 9,123,700 | +4.7% |

| 2008 | 9,542,800 | +4.6% |

| 2009 | 9,950,100 | +4.3% |

| 2010 | 10,372,000 | +4.2% |

| 2011 | 10,467,400 | +0.9% |

| 2012 | 10,547,400 | +0.8% |

| 2013 | 10,628,900 | +0.8% |

| 2014 | 10,778,900 | +1.4% |

| 2015 | 11,378,700 | +5.6% |

| 2016 | 11,908,400 | +4.7% |

| 2017 | 12,528,300 | +5.2% |

| 2018 | 13,026,600 | +4.0% |

| 2019 | 13,438,800 | +3.2% |

| Shenzhen Statistical Yearbook, 2020[1] | ||

As of 2020, Shenzhen had a total permanent population of 17,560,000, with 5,874,000 (33.4%) of them hukou holders (registered locally).[2][3][4][5] As Shenzhen is a young city, senior citizens above 60 years old took up only 5.36 percent of the city's total population.[2] Despite this, the life expectancy in Shenzhen is 81.25 in 2018, ranking among the top twenty cities in China.[6] The male to female ratio in Shenzhen is 130 to 100, making the city having the highest sex disparity in comparison to other cities in Guangdong.[2] Shenzhen also has a high birth rate compared to other Chinese cities with 21.7 babies for every 10,000 of its 13.44 million population in 2019.[7] Based on the population of its total administrative area, Shenzhen is the fifth most populous city proper in China.[8] Shenzhen is part of the Pearl River Delta Metropolitan Region (covering cities such as Guangzhou, Dongguan, Foshan, Zhongshan, Zhuhai, Huizhou, Hong Kong, and Macau), the world's largest urban area according to the World Bank,[9] and has a population of 78 million according to the 2020 Census.[2]

Before Shenzhen's establishment as a SEZ in 1980, the area was composed mainly of Hakka and Cantonese people.[10] When the SEZ was established, the city attracted migrants from all around Guangdong, including Hakka, Cantonese, and Teochew, as well as migrants from Southern and Central Chinese provinces such as Hunan, Guangxi, Jiangxi, Sichuan, and Henan.[11] Most of these migrants live in urban villages called chengzhongcun (城中村; 'village in the city') such as Baishizhou in the Nanshan District.[12] Shenzhen also has a notable Korean minority based in the Nanshan District and the Futian District, with migrants moving to Shenzhen to work for South Korean companies that had branched out in the city when China has opened up.[13][14]

Due to Shenzhen's population overshooting the 14.8 million population target for 2016 to 2020, the Shenzhen justice bureau on 25 May 2021 had announced it would make it harder to earn a hukou to live in the city.[3] In regards to the registered population (hukou), Shenzhen has seen an increase of 2.178 million or 58.9% of registered residents in the city from 2015 to 2020.[11] In regards to permanent population, the city has seen an increase of 7,136,088 or 68.46% of permanent residents in the city from 2010 to 2020, creating an average annual growth rate of 5.35%.[4]

Historic

Legend:

There had been migration into southern Guangdong province and what is now Shenzhen since the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) but the numbers increased dramatically since Shenzhen was established in the 1980s. In Guangdong province, it is the only city where the local languages (Cantonese, Shenzhen-Hakka and Teochew) is not the main language; it is Mandarin that is mostly spoken, with migrants/immigrants from all over China.

Shenzhen has seen its population and activity develop rapidly since the establishment of the SEZ as a magnet for migrants, beginning with blue collar or labor-intensive workers, giving the city the moniker 'the world's factory'. Shenzhen had an official population of over 10 million during the 2011 census. However, due to the large unregistered floating migrant population living in the city, some estimates put Shenzhen's actual population at around 20 million inside the administrative area given at any specific moment.[15][16] The population growth of Shenzhen follows large scale trends; around 2012–13, the city's estimated growth slowed down to less than 1 percent due to rising migrant labor costs, migrant worker targeted reforms, and moving of factories out to periphery and neighboring Dongguan. By 2015, the high tech economy began to gradually replace the labor-intensive industries as the city gradually became a magnet for a new generation of migrants, this time educated, white collar workers. Migration into Shenzhen was further promoted by hard population caps imposed on other Tier I cities like Beijing and Shanghai, previously the top destinations for white collar workers. By the end of 2018, the official registered population had been estimated as just over 13 million a year over year increase of 500,000.[17]

By 2020 the official population count was 17,560,000, leading to changes in residency requirements to discourage further migration into Shenzhen.[18]

University of Wisconsin-Madison China demographics specialist Yi Fuxian stated that Shenzhen's birthrate was below 1.05, which while the highest of major cities in China, was not at the replacement level needed.[19]

Other statistics

At present, the average age in Shenzhen is less than 30. The age range is as follows: 8.49% between the age of 0 and 14, 88.41% between the age of 15 and 59, and 3.1% aged 65 or above.[20]

The population structure has great diversity, ranging from intellectuals with a high level of education to migrant workers with poor education.[21] It was reported in June 2007 that more than 20 percent of China's PhD graduates had worked in Shenzhen.[22] Shenzhen was also elected as one of the top 10 cities in China for expatriates. Expatriates choose Shenzhen as a place to settle because of the city's job opportunities as well as the culture's tolerance and open-mindedness, and it was even voted China's Most Dynamic City and the City Most Favored by Migrant Workers in 2014.

According to a survey by the Hong Kong Planning Department, the number of cross-border commuters increased from about 7,500 in 1999 to 44,600 in 2009. More than half of them lived in Shenzhen.[23] Though neighboring each other, daily commuters still need to pass through customs and immigration checkpoints, as travel between the SEZ and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) is restricted.

Mainland residents who wish to enter Hong Kong for visit are required to obtain an "Exit-Entry Permit for Travelling to and from Hong Kong and Macao". Shenzhen residents can have a special 1 year multiple-journey endorsement (but maximum 1 visit per week starting from April 13, 2015) This type of exit endorsement is only issued to people who have hukou in certain regions.[24](See Exit-Entry Permit for Travelling to and from Hong Kong and Macau.)

Ethnic groups

Ethnic Koreans

As of 2007 there were about 20,000 people of Korean origins in Shenzhen, with the Nanshan and Futian districts having significant numbers. That year the chairperson of the Korean Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Kang Hee-bang, stated that about 10,000 lived in Overseas Chinese Town (OCT). Shekou, the area around Shenzhen University, and Donghai Garden housing estate had other significant concentrations.[25] Donghai Garden began attracting Koreans due to its transportation links and because, around 1998, it was the sole residential building classified as 3-A. As of 2014 Donghai had about 200 Korean families.[26]

South Koreans began going to the Shenzhen area during the 1980s as part of the reform and opening up era, and this increased when South Korea established formal diplomatic relations with the PRC.[26]

In 2007 about 500 South Korean companies in Shenzhen were involved in China-South Korean trade, and there were an additional 500 South Korean companies doing business in Shenzhen. In 2007 Kang stated that most of the Koreans in Shenzhen had lived there for five years or longer.[25]

There is one Korean international school in Shenzhen, Korean International School in Shenzhen. As of 2007 there were some Korean children enrolled in schools for Chinese locals.[25] As of 2014 spaces for foreign students in Shenzhen public schools were limited, so some Korean residents are forced to put their children in private schools.[26] In addition, in 2007, there were about 900 Korean children in non-Chinese K-12 institutions; the latter included 400 of them at private international schools in Shekou, 300 in private schools in Luohu District, and 200 enrolled at the Baishizhou Bilingual School. Because many Korean students are not studying in Korean-medium schools, the Korean Chamber of Commerce and Industry operates a Korean Saturday School; it had about 600 students in 2007. The chamber uses rented space in the OCT Primary School as the Korean weekend school's classroom.[25]

Languages and religions

Prior to the establishment of Special Economic Zone, the indigenous local communities could be divided into Cantonese and Hakka speakers,[27] which were two cultural and linguistic sub-ethnic groups vernacular to Guangdong province. Two Cantonese varieties were spoken locally. One was a fairly standard version, known as standard Cantonese. The other, spoken by several villages south of Fuhua Rd. was called Weitou dialect.[28] Two or three Hong Kong villages south of the Shenzhen River also speak this dialect. This is consistent with the area settled by people who accompanied the Southern Song court to the south in the late 13th century.[29] Younger generations of the Cantonese communities now speak the more standard version. Today, some aboriginals of the Cantonese and Hakka speaking communities disperse into urban settlements (e.g. apartments and villas), but most of them are still clustering in their traditional urban and suburban villages.[30]

The influx of migrants from other parts of the country has drastically altered the city's linguistic landscape, as Shenzhen has undergone a language shift towards Mandarin, which was both promoted by the Chinese Central Government as a national lingua franca and natively spoken by most of the out-of-province immigrants and their descendants.[31][32][33] However, in recent years multilingualism is on the rise as descendants of immigrants of out-of-province Mandarin native speakers begin to assimilate into the local culture through friends, television and other media.[34] Despite the ubiquity of Mandarin Chinese, local languages such as Cantonese, Hakka, and Teochew are still commonly spoken among locals. Hokkien and Xiang are also sometimes observed.

According to the Department of Religious Affairs of the Shenzhen Municipal People's Government, the two main religions present in Shenzhen are Buddhism and Taoism. Every district also has Protestant churches, Catholic churches, and mosques.[35] According to a 2010 survey held by the University of Southern California, approximately 37% of Shenzhen's residents were practitioners of Chinese folk religions, 26% were Buddhists, 18% Taoists, 2% Christians and 2% Muslims; 15% were unaffiliated to any religion.[36] Most new migrants to Shenzhen rely upon the common spiritual heritage drawn from Chinese folk religion.[37][38] Shenzhen also hosts the headquarters of the Holy Confucian Church, established in 2009.[39]

See also

References

- ↑ 3-2 户数、人口、出生、死亡及自然增长. Shenzhen Statistical Yearbook 2020 [Households, Population, Birth, Death and Natural Growth] (PDF) (in Chinese and English). p. 55. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-07-27. - Web version - See column "年末常住人 口数 (万人) Year-end Permanent Population (10 000 persons)". The original source expresses figures in ten thousands. Here the numbers are converted to the ordinary format.

- 1 2 3 4 "City population stands at 17.56 million_Latest News-Shenzhen Government Online". www.sz.gov.cn. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- 1 2 "China's Shenzhen to tighten residency rules to curb population boom". www.msn.com. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- 1 2 "深圳市第七次全国人口普查公报[1](第一号)——全市常住人口情况--统计公报". www.sz.gov.cn. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ↑ "户籍人口5年新增200多万!深圳要收紧落户了?". finance.ifeng.com. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ↑ "Shenzhen". U.S. Commercial Service. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2008.

- ↑ "Shenzhen shows challenge of reversing China's demographic decline despite high birth rate". The Straits Times. 2021-05-10. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ↑ 2017年深圳经济有质量稳定发展 [In 2017, Shenzhen economy will have stable quality and development] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ↑ Mead, Nick Van (2015-01-28). "China's Pearl River Delta overtakes Tokyo as world's largest megacity". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-08-21.

- ↑ 深圳客家文化的历史追问. 深圳新闻网. 2003-06-22. Archived from the original on 2012-06-06. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- 1 2 网易 (2020-08-26). "深圳人口图鉴:86%的人在打拼 外省人中湖南占比最多". www.163.com. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ↑ "Migrant workers forced out as 'urban village' faces wrecking ball". South China Morning Post. 2019-07-22. Retrieved 2021-06-18.

- ↑ "South Koreans find new home in Donghai". Shenzhen Daily. 2014-07-01. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ↑ "ShenZhen, Koreans' second hometown". Shenzhen Daily at China.org.cn. 2007-09-28. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ↑ Li, Zhu (李注). 深圳将提高户籍人口比例 今年有望新增38万_深圳新闻_南方网. sz.Southcn.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ 深圳大幅放宽落户政策 一年户籍人口增幅有望超过10%. finance.Sina.com.cn. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ "深圳户籍人口增幅有所放缓 2018年年末常住人口1302万人_移民城市". www.sohu.com. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ↑ "China's Shenzhen to tighten residency rules to curb population boom". Channel News Asia. 2021-05-26. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ↑ Kirton, David (2021-05-10). "Despite highest birth rate, Shenzhen shows challenge of reversing China's demographic decline". Reuters. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ↑ "Age Composition and Dependency Ratio of Population by Region (2004)". China Statistics 2005. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ Shenzhen Government Online, Citizens' Life (Recovered from the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ Shenzhen Daily 13 June 2007

- ↑ "Cross-border Commuters Live Hard between Hong Kong and Shenzhen | Feed Magazine - HKBU MA International Journalism Student Stories". journalism.hkbu.edu.hk. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ 广东省公安厅出入境政务服务网. www.gdcrj.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "ShenZhen, Koreans' second hometown". Shenzhen Daily at China.org.cn. 2007-09-28. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- 1 2 3 "South Koreans find new home in Donghai". Shenzhen Daily. 2014-07-01. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- ↑ 深圳客家人的來歷和客家民居 [Hakka Origins and Settlements in Shenzhen]. 中國國際廣播電臺國際線上. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ 圍頭話 Weitou dialect. Archived from the original on 15 December 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ Rule, Ted and Karen, Shenzhen the Book Hong Kong 2014

- ↑ 張 ZHANG, 則武 Zewu. 浅谈深圳城中村的成因及其影响 A Discussion concerning the History and Consequences of Urban Villages in Shenzhen. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ 秦 CHUN, 炳煜 Bing Yuk (7 July 2006). 深圳成粵語圈中普通話區 Shenzhen becomes the Mandarin area in a Cantonese region. 文匯報 Wenweipo. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ 深圳將粵語精髓融入普通話 Shenzhen Incorporates Cantonese Essence into Mandarin. 南方網. 15 February 2012. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ 中华人民共和国国家通用语言文字法 The National Lingua Franca and Orthography Act-- People's Republic of China. Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. Archived from the original on 18 May 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ He, Huifeng. "Trendy Shenzhen teenagers spearhead Cantonese revival". South China Morning Post. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ 中共深圳市委统战部(市民族宗教事务局、市侨务办公室、市侨联). www.tzb.sz.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ Demographics of religion in Shenzhen() for the "6 under 60 Archived 25 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine" research project by the University of Southern California. See also Lani Heidecker's data for the Shenzhen Geography Project().

- ↑ Fan, Lizhu; Whitehead, James D. (2011). "Spirituality in a Modern Chinese Metropolis Archived 22 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine". In Palmer, David A.; Shive, Glenn; Wickeri, Philip L. Chinese Religious Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199731381

- ↑ Lizhu, Fan; Whitehead, James D. (2004). "Fate and Fortune: Popular Religion and Moral Capital in Shenzhen". Journal of Chinese Religions. 32: 83–100. doi:10.1179/073776904804759969.

- ↑ Payette, Alex. "Shenzhen's Kongshengtang: Religious Confucianism and Local Moral Governance Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine". Role of Religion in Political Life, Panel RC43, 23rd World Congress of Political Science, 19–24 July 2014.