| Deddington Castle | |

|---|---|

North embankment of the western bailey, with the castle motte on the right | |

| Type | Earthworks only |

| Location | Deddington, Oxfordshire, England |

| Coordinates | 51°58′51″N 1°18′56″W / 51.9809°N 1.3156°W |

| OS grid reference | SP471316 |

| Built by | Bishop Odo of Bayeux |

| Owner | English Heritage and Deddington parish council |

| Important events | Death of Piers Gaveston English Civil War |

| Official name | Deddington Castle |

| Designated | 7 March 1951 |

| Reference no. | 1014749[1] |

Location of Deddington Castle in Oxfordshire | |

Deddington Castle is an extensive earthwork in the village of Deddington, Oxfordshire, all that remains of an 11th-century motte-and-bailey castle, with only the earth ramparts and mound now visible.

The castle was built on a wealthy former Anglo-Saxon estate by Bishop Odo of Bayeux, half-brother of William the Conqueror. It was strengthened in the 12th century, with some stone defences added, but from the 13th century onwards it fell into disrepair, and the stone buildings were eventually dismantled and sold.

The castle played a minor part in the English Civil War, but after Deddington's strategic importance waned, the site lay vacant for many decades, used only for grazing and forestry.

In the 19th century the site was used for recreation and sports, until it was sold to the parish council in 1947. It now serves as a park and nature walk. The site is protected under UK law as a scheduled monument.[1]

History

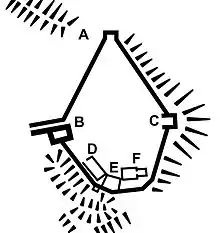

Following the Norman conquest of England in 1066, Odo constructed this large castle with two earthwork baileys and a central motte, intending that the castle administer his property in the region and provide a substantial military base in the event of an Anglo-Saxon revolt. Odo's estates in England were seized following a failed rebellion against William II in 1088, and Deddington Castle was taken back into royal control. The Anglo-Norman lord William de Chesney acquired the castle in the 12th century and rebuilt it in stone, raising a stone curtain wall around a new inner bailey, complete with a defensive tower, gatehouse and domestic buildings.

After de Chesney's death, his descendants fought for control of the castle in the royal courts, and it was temporarily seized several times by King John at the start of the 13th century. Deddington Castle was confirmed in the ownership of the de Dive family, who held it for the next century and a half. In 1281, the castle was stormed by a group of men who broke down the doors, and in 1312 the royal favourite Piers Gaveston may have been captured at the castle by his enemies, shortly before his execution. From the 13th century onward, Deddington Castle fell into disrepair, and contemporaries soon described it as "demolished" and "weak". It was bought by the Canons of Windsor in 1364, who began to sell off its stonework. The remains of the castle were reportedly used by both Royalist and Parliamentary forces during the English Civil War in the 17th century.

In the 19th century Deddington Castle was adapted for use as a sporting facility by the local gentry. It was sold to Deddington's parish council, who attempted to build tennis courts in the inner bailey in 1947. Following the discovery of medieval remains and a subsequent archaeological investigation, these plans were abandoned and the western half of the castle became a local park. In the 21st century, English Heritage manage the inner bailey, the eastern half remaining in use for farming, and the site as a whole is protected under UK law as a scheduled monument.

11th century

At this time Deddington was one of the largest settlements in the county of Oxfordshire, and the site of the castle had been previously occupied by the Anglo-Saxons, who may have used the location to administer one of their landed estates.[2] Odo was the half-brother of William the Conqueror, who granted the bishop vast lands in England after the invasion, spread across 22 different counties.[3] Deddington was one of the richest of Odo's new manors and was at the centre of his Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire estates.[4] The castle was probably built to act as the caput, or administrative centre, of his lands in the region, and may have also been intended to quarter a large military force in the event of an Anglo-Saxon revolt.[5]

The castle was positioned on the east side of the main part of the settlement at the time, at the opposite end of the village to the church, on a spur overlooking a nearby stream.[6] Odo erected earthworks to enclose two large baileys of around 3.4 hectares (8.4 acres) each, with a large raised motte positioned in between.[7] The western bailey was around 170 metres (560 ft) by 240 metres (790 ft), protected by a bank of earth 5 metres (16 ft) tall from the base of the 15 metres (49 ft) wide ditch.[1] The top of the earthworks formed a rampart 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) across.[1] The western bailey had an entrance on the west side and in the north-east corner.[1] The eastern bailey stretched down the hill to the stream, and may have held two fishponds.[1] Another fishpond called "the Fishers", further along the stream to the south-east of the castle, was also probably linked to the castle site.[6] Around this time, an L-shaped stone hall was constructed near the motte, in the western bailey.[8]

The castle's layout was unusual for the region during this period, where the fortifications built by the Normans were typically smaller ringwork designs, and it highlighted both the strategic importance of the location and the power of its builder.[9] In scale and design it was similar to the initial version of Rochester Castle, another major fortification built by Odo in England.[5]

Odo unsuccessfully rebelled against William II in 1088 and in the aftermath was stripped of his lands.[10] His manors across Oxfordshire were taken back into royal control and broken up to be granted to sub-tenants, although it is unclear who was initially granted Deddington Castle; it is possible that the powerful Anglo-Norman baron Robert de Beaumont, the Earl of Leicester, controlled it in 1130.[11]

1100–1215

In the early 12th century, additional earthworks were thrown up to divide the western half of the castle into an outer bailey of around 3 hectares (7.4 acres) and an inner bailey on the east end, comprising around 0.4 hectares (0.99 acres).[12] The earthworks pushed up against the older hall, and partially buried its western walls.[8] It is uncertain exactly why the new earthworks were constructed, but it may have been to strengthen the fortification in response to either the threatened invasion of Duke Robert of Normandy in 1101, or alternatively to the sinking of the White Ship and the subsequent dynastic crisis in 1120.[13]

By 1157, the castle was owned by William de Chesney, an Anglo-Norman lord who had supported King Stephen in the region during the civil war of the Anarchy, and then Henry II after the peace in 1154.[14] William rebuilt much of the castle, constructing a strong stone curtain wall around the inner bailey, 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) thick and made from mortared ironstone rubble.[15] The wall was cut through the motte, the inner part of the mound being dug away to make room for the wall.[16]

William also began to reconstruct the inside of the inner bailey, a programme of work that was continued by his descendants over the next few decades.[8] The work included a chapel, a hall and solar, and various service buildings.[8] An open-backed square tower was built in stone along the wall on top of the motte; this tower was later rebuilt, possibly because of pressure on it from the motte earthworks, and the top of the motte was relaid with flagstones to form pathways around the top.[17] A stone gatehouse was built on the west side of the wall, leading from the outer bailey.[8]

William died between 1172 and 1176, and the castle was then granted the Crown to Ralph Murdac, William's nephew and a favoured supporter of Henry II.[18] Ralph was unpopular, however, with Henry's successor, Richard I, and Ralph's relatives Guy de Dive and Matilda de Chesney took the opportunity to sue him in the royal courts, each claiming a third of William's estate.[19] The lands around the castle were granted to Guy and, renamed the "Castle Manor", remained in his family line until the mid-14th century.[20] When King John took the throne, however, he seems to have seized Deddington. The manor was not returned to Guy until 1204; furthermore, Deddington Castle was excluded from this agreement and retained in royal control until the following year.[21] On Guy's death in 1214, John again took the castle back into royal control, where it remained until the King's own death the following year.[21]

1215–18th century

Both the village and the castle of Deddington fell into decline during the 13th century.[22] Although the village had grown to become a borough, with new, planned streets spreading westwards away from the castle, it was eclipsed economically by the nearby, newer centre of Banbury.[21] The castles in the Thames Valley region that lacked substantial defences were mostly abandoned during this period and Deddington Castle was no exception.[23] By 1277 contemporaries described it as "an old demolished castle".[24] In 1281, Robert of Aston and a group of men were able to break down the doors to the castle and enter it.[21] The castle was considered to be "weak" in a report of 1310 and no further repairs were carried out on the property after this time.[21]

In 1312, the royal favourite Piers Gaveston may have been captured at Deddington Castle.[25] Gaveston was a close friend of Edward II but he had many enemies among the major barons, and had surrendered to them on the promise that he would be unharmed.[26] He was taken south by Aymer de Valence, the Earl of Pembroke, who imprisoned Gaveston at Deddington on 9 June while he left to visit his wife.[21] Gaveston is often stated to have been kept in Deddington Castle, although he may have alternatively been lodged in the rectory house in the village.[25] Guy de Beauchamp, the Earl of Warwick, had a particular dislike of Gaveston and the next morning took the opportunity to seize him and take him back to Warwick Castle, where Gaveston was subsequently tried and killed by his enemies.[27]

During the 14th century the interior of the castle continued to be inhabited, but in a manner that archaeologist Richard Ivens likens to "squatting": the upper levels of the tower were abandoned and wood burnt along the inside of the walls in a crude fireplace.[28] In 1364, the Canons of Windsor bought the castle, park and former fishponds from Thomas de Dive; the Canons rented the farmlands out, but retained the right to operate and profit from the castle's manorial court.[20] The tower was demolished around this time, possibly linked to the sale of stonework from the castle walls in 1377 to the Canons of Bicester.[28] By the 16th century, the visiting antiquarian John Leland only noted that "there hath bene a castle at Dadintone".[29]

The village of Deddington was extensively involved in the English Civil War between 1641 and 1645, owing to its location on the route between Banbury and Oxford.[21] The late 19th-century historian James Mackenzie recorded that the castle was used as a temporary fortress by both Royalist and Parliamentary forces during the conflict and that a Royalist garrison was besieged there by Parliamentary troops in 1644.[30] During the 17th and 18th centuries, the castle site was used for grazing animals and timber farming.[21]

19th–21st centuries

From the 19th century, the castle site was used as club by the local gentry for recreation, including cricket and archery.[21] A small lodge was built at the entrance to house a professional coach, and a "pavilion building" – a combination of a ballroom and a cafe – was built within the grounds.[21] In 1886, the ownership of the site passed from the Canons of Windsor to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners of the Church of England.[21] The pavilion was demolished at the start of the 20th century.[21] Stonework continued to be taken from the remains of the castle up until the 1940s, for use in local buildings.[31]

From 1945 until 1981 the Castle was home to Deddington and District Rifle and Revolver Club.

In 1947 the castle site was sold by the Commissioners to Deddington's parish council.[21] The parish council intended to build tennis courts in the inner bailey of the castle, but when work began, medieval pottery and roof tiles were unearthed by the builders.[32] Construction work was halted and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford sponsored an archaeological investigation by Edward Jope and Richard Threlfall that continued until 1953.[33] The plans for the tennis courts were dropped in light of the findings, and the site was instead used as a park.[34] A further phase of archaeological investigation of the castle was carried out between 1977 and 1979, sponsored by the Queen's University Belfast and led by Richard Ivens.[35]

In the 21st century, only the earthworks of the castle remain.[1] The western bailey is managed by the parish council and the inner bailey by English Heritage, while the eastern bailey remains under cultivation.[1] The site is protected under UK law as a scheduled monument.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Historic England. "Deddington Castle (1014749)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ↑ Ivens 1983, p. 35; Pounds 1994, p. 61; "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ↑ Ivens 1984, p. 101

- ↑ Ivens 1984, p. 108

- 1 2 Ivens 1984, pp. 113–114; Creighton 2005, p. 37

- 1 2 "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013; "List Entry Summary: Deddington Castle", English Heritage, archived from the original on 17 December 2013, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ↑ Ivens 1983, p. 35; Ivens 1984, pp. 111, 113; "List Entry Summary: Deddington Castle", English Heritage, archived from the original on 17 December 2013, retrieved 15 December 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ivens 1984, p. 111

- ↑ Ivens 1984, pp. 113–114

- ↑ Ivens 1984, p. 114; Pounds 1994, p. 61

- ↑ Ivens 1984, pp. 114–115

- ↑ Ivens 1983, p. 35; Ivens 1984, p. 111

- ↑ Ivens 1984, pp. 112–115

- ↑ Ivens 1983, p. 35; Ivens 1984, p. 112

- ↑ Ivens 1983, p. 37; Ivens 1984, p. 111

- ↑ Ivens 1983, p. 37

- ↑ Ivens 1983, pp. 37–39

- ↑ Ivens 1984, p. 115; "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ↑ Ivens 1984, p. 115

- 1 2 Ivens 1984, p. 117; "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ↑ "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013; Ivens 1984, p. 117

- ↑ Emery 2006, p. 15; Ivens 1984, p. 117

- ↑ Emery 2006, p. 15; Ivens 1984, p. 117; "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013

- 1 2 "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013; Pettifer 2002, p. 204

- ↑ Prestwich 2003, pp. 74–75

- ↑ Prestwich 2003, pp. 75–76

- 1 2 Ivens 1983, p. 39

- ↑ "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013; Ivens 1984, p. 118

- ↑ Mackenzie 1896, p. 155

- ↑ Ivens 1984, p. 112

- ↑ Jope & Threlfall 1946–1947, p. 167

- ↑ Jope & Threlfall 1946–1947, p. 167; Ivens 1983, p. 35

- ↑ Jope & Threlfall 1946–1947, p. 167; "Parishes: Deddington', A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 11: Wootton Hundred (Northern Part) (1983), pp. 81–120", Victoria County History, retrieved 15 December 2013

- ↑ Ivens 1983, p. 35

Bibliography

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton (2005). Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London, UK: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.

- Emery, Anthony (2006). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500. Volume 3, Southern England. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5.

- Ivens, Richard J. (1983). "Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire. A Summary of Excavations 1977–1979". South Midlands Archaeology: CBA Group 9 Newsletter (13): 34–41.

- Ivens, Richard J. (1984). "Deddington Castle, Oxfordshire, and the English honour of Bayeux". Oxoniensia (49): 101–119.

- Jope, Edward M.; Threlfall, Richard I. (1946–1947). "Recent Mediaeval Finds in the Oxford District". Oxoniensia (11–12): 167–168.

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896). The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure. Vol. 2. New York, US: Macmillan. OCLC 504892038.

- Pettifer, Adrian (2002). English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Prestwich, Michael (2003). The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272–1377 (2nd ed.). London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30309-5.