Thousands of Jews lived in the towns of Dęblin and Irena[lower-alpha 1] in central Poland before World War II; Irena was the site of the Polish Air Force Academy from 1927. In September 1939, the town was captured during the German invasion of Poland and the persecution of Jews began with drafts into forced labor and the establishment of a Judenrat ("Jewish Council"). A ghetto was established in Irena in November 1940. It initially consisted of six streets and was an open ghetto (the Jews were not allowed to leave without permission, but non-Jews could enter). Many ghetto inhabitants worked on labor projects for Dęblin Fortress (a German Army base), the railway, and the Luftwaffe. Beginning in May 1941, Jews were sent to labor camps around Dęblin from the Opole and Warsaw ghettos. Conditions in the ghetto worsened in late 1941 due to increased German restrictions on ghetto inhabitants and epidemics of typhus and dysentery.

The first deportation was on 6 May 1942 and took around 2,500 Jews to Sobibór extermination camp. A week later, two thousand Jews arrived from Slovakia and hundreds more from nearby ghettos that had been liquidated.[lower-alpha 2] In October that same year, the Irena ghetto was liquidated; about 2,500 Jews were deported to Treblinka extermination camp while some 1,400 Jews were retained as inmates of forced-labor camps in the town. Unusually, the labor camp operated by the Luftwaffe—employing, at its peak, about a thousand Jews—was allowed to exist until 22 July 1944, less than a week before the area was captured by the Red Army. One of the last Jewish labor camps in the Lublin District, it enabled hundreds of Jews to survive the Holocaust. Some survivors who returned home were met with hostility, and several were murdered; all left by 1947.

Background

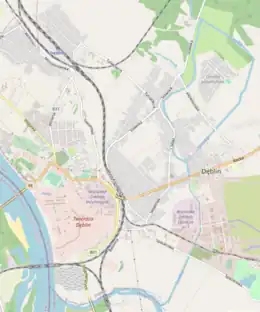

Dęblin and Irena[lower-alpha 1] (Yiddish: מאדזשיץ, Modzhitz)[3] are located 70 kilometers (40 mi) northwest of Lublin in Poland,[2] at the confluence of the Vistula and Wieprz rivers and at an important junction on the Lublin–Warsaw rail line.[4] Local Jews supported the January Uprising in 1863. By the end of the nineteenth century, the area was a center of Hasidic Judaism; most Jews followed the Modzitz dynasty, named after the town of Irena, and there were also Gur Hasidim. Modzitz Rebbe Yisrael Taub settled in the town in 1889.[4][5] Other Jews were Bundists or Zionists.[3] Many Jews made their living as peddlers, shopkeepers, or artisans (especially in leatherwork and metalwork) and later participated in the development of the town as a summer resort.[3][6] In 1927, the civilian population of Dęblin and Irena was 4,860, including 3,060 Jews.[2] Beginning in 1927, Dęblin housed the Polish Air Force Academy,[7] whose airfield was one of the largest in Poland.[8] In 1936 and 1937, there were some incidents in which non-Jewish merchants vandalized their Jewish competitors' shops.[9]

German invasion

During the German invasion of Poland which started World War II in Europe, the Luftwaffe bombed Dęblin between 2 and 7 September 1939,[2] targeting the military airfield, Polish Army ammunition stores, and a nearby bridge over the Vistula. Most Polish soldiers left the town on 7 September; on 11 September the remaining Polish forces detonated the ammunition and withdrew.[9] The German Army arrived on 12 or 20 September.[2][3] Many residents, both Jews and other residents of the area, had fled to escape the aerial bombardment. In the following weeks, most returned at the urging of the Germans. The Jews found that their properties had been ransacked and plundered. They were conscripted into forced-labor units that cleared up the bomb damage and repaired some of the buildings, and the Jewish community was forced to pay a fine of 20,000 zlotys.[3][2][10] During the German occupation, Dęblin and Irena became part of the Lublin District of the General Governorate occupation region. In late 1939, Jews were required to wear armbands with the Star of David, and some were conscripted for forced labor in Janiszów, Bełżec, and Pawłowice.[11]

At the end of the year, the German occupiers forced Jews to form a Judenrat ("Jewish Council"), as an interface between the Jewish community and Nazi demands.[2][3] The Judenrat was formed later than others in the region[12] and had its offices on Bankowa Street.[9] The first Judenrat officials worked to reduce the impact of German demands and warned residents of searches. According to the Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, the first chair of the Judenrat, Leizer Teichman, was dismissed in early 1941; survivors reported that he and his secretary were deported to Wąwolnica with their families after trying to bribe policemen. The Judenrat was run temporarily by Kalman Fris, who resigned after a few months and was replaced by Vevel Shulman in August and then a Konin native named Drayfish in September 1941.[11] According to Israeli historian David Silberklang, "Szymon Drabfisz" was the first chair and Teichman the second.[13]

Ghetto

| External image | |

|---|---|

A Nazi ghetto was established in Irena in November 1940[14] or early 1941, probably on the orders of Kurt Lenk, the region's new land commissioner.[11] Some Jews were forced to move from their homes to the ghetto. The motive was probably to keep Jews away from the two nearby military installations, a Luftwaffe airfield and a German Army base, which were filled with troops in preparation for the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. The decree establishing the ghetto was not formally issued until 1942.[11] Until 1942,[3] Irena was an open ghetto (there was no physical fence, although the penalty for unauthorized departure was death) consisting of six streets. Its boundaries were initially Okólna Street, the Irenka River, Bankowa, and Staromiejska Streets. Staromiejska Street was removed from the ghetto in September 1942; its residents moved to Bankowa. Initially, non-Jews were allowed to enter and perhaps live in the ghetto, so many of the Jews were able to survive by trading material goods for food with them.[11] A Polish-language secular school, run by Aida Milgroijm-Citronbojm, instructed 70 to 100 pupils.[11][15] The Jewish Ghetto Police maintained order in the ghetto, and on the outside it was guarded by a Sonderdienst ("Special Services") unit consisting of local Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) and Ukrainian Auxiliary Police. The Sonderdienst unit was known for beating, humiliating, and killing ghetto inmates.[11]

In late 1941, non-Jewish Poles were banned from entering the ghetto, resulting in waste piling up and typhus and dysentery epidemics. The sick were treated at a thirty-bed hospital run by Isaar Kawa, a doctor from Konin; with the help of non-Jewish doctors, medicines were imported from Warsaw.[14][11] Simultaneously, new restrictions were imposed by the Germans: the use of stoves was banned, winter clothing confiscated, and fuel imports forbidden.[15][11] More Jews began to leave the ghetto to obtain essentials, resulting in twenty young women being discovered outside the ghetto and killed.[16] Because conditions were better in Lublin District than in Warsaw, some Jews fled to towns there including Irena;[17] twenty Jews were executed for being unregistered refugees. The Judenrat's leadership was altered again as Drayfish was executed, accused of filing complaints with the Puławy County administration; he was replaced by the businessman Yisrael Weinberg.[16]

In March 1941, 3,750 Jews lived in the ghetto, including 565 who were not from the area. These consisted mainly of Jews expelled from Puławy and the German-annexed Reichsgau Wartheland, as well as some Jews who had come to live with relatives to avoid being trapped in the Warsaw Ghetto. Overcrowding was severe; there were 7–15 people per room. More Jews arrived in May 1941: 1,000 from the ghettos at Warsaw, Częstochowa, and Opole, although they were not housed in the ghetto but at work sites in the area.[11] On 13 and 14 May 1942, two transports totalling 2,042 Slovak Jews arrived from Prešov.[16][18] Although they brought food with them, they were unused to the harsh conditions and many died of typhus due to the poor sanitation.[16][19] More than 2,000 Jews were brought to Irena from nearby towns, having survived the liquidation[lower-alpha 2] of their communities because they had been selected to work. These included 300 people from Ryki, 300 from Gniewoszów and Zwoleń, and a group from Stężyca. Other Jews had entered the ghetto after escaping roundups in Baranów, Ryki, Gniewoszów, and Adamów (from early October). In August, 5,800 Jews were reported to be living in the ghetto, of whom only 1,800 were from Dęblin.[16]

Forced labor

Until late 1942, Jews earned wages as forced laborers, except those who were conscripted by the municipality for tasks such as street cleaning or snow clearing. Some Jews worked for German companies such as Schwartz and Hochtief, contracted by the Wehrmacht to do construction on the military bases in the town. The Ostbahn contracted Schultz to improve the railway between Lublin and Warsaw, a project which employed 300 Jews beginning in June 1941. Working conditions at this site were very harsh with Jews forced to work twelve hours each day.[11][20] However, most Jews worked for the German Army or the Luftwaffe; women and children grew food for the military.[11] Dęblin Fortress, which had been taken over by the German Army and where around 200 Jews from the ghetto worked,[8] was the site of Stalag 307, a camp for Soviet prisoners of war, from 10 July 1941.[15][21][22] An estimated 80,000 Soviet prisoners were imprisoned there; all died within a few months of starvation and disease.[21][23] The Jews who worked there saw prisoners held in worse conditions than their own.[24] The Jews from Dęblin and Irena tried to take the best jobs; 200 of the Slovak deportees ended up working for the municipality. An additional 200 of the Slovaks worked for the Schultz firm following an expansion.[16] Survivors recalled that although German soldiers supervising the forced laborers tended to treat them relatively well, some ethnic Polish supervisors beat Jews, and the Ukrainian guards at the railway project were especially harsh, threatening prisoners with death.[25]

In May 1941, in preparation for the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Luftwaffe commissioned the firm Autheried to improve the airfield.[26] They recruited 200 Jewish workers in Opole, many of whom were Austrian Jews who had been deported from Vienna in February 1941 and wanted to escape the harsh conditions in Opole.[26] These Jews, as well as another four hundred recruited in Irena and the Lipowa 7 camp in Lublin,[11][26] and 500 ethnic Polish workers, worked twelve hours a day levelling the runway and building roads, walls, air-raid shelters, and earth fortifications. They also built a barbed-wire-enclosed complex adjacent to the runway for craftsmen to work in.[26] Following the completion of the project in October, the workers were dispersed to various projects around the town, an action which may have been related to the typhus epidemic.[11][26] Some of the Jews from Vienna stayed at the airfield, having obtained permits to work on gravel transportation and building fuel tanks; they were the nucleus for the later labor camp. After the first deportation from the Irena ghetto on 6 May 1942, additional Jews tried to secure permits, often obtained through bribery, to avoid deportation. By October 1942, the camp had 543 legal residents.[26] At this point there were five forced-labor camps around Dęblin: the Luftwaffe camp, the fortress, the train station (300 Jews), Lipova Street (200 Jews and ethnic Poles), and another near the municipal boundary (300 Jews).[27]

Deportation, murder, and liquidation

First deportation

The first deportation was on 6 May 1942,[16][28][29] to clear space for the Slovak deportees who arrived a week later.[16][30] A force composed of German and Ukrainian police and a few German SS and Ukrainian SS auxiliaries ordered Jews to assemble in the main square at 09:00.[16][20] According to Yad Vashem, the Blue Police also participated.[31] Probably because the Luftwaffe was seeking permission to recruit more laborers, the Jews had to wait for five hours. At 14:00, 1,000 Jews who already had work assignments were separated, and local employers began recruiting an additional 200–500 Jews. Forty or fifty people were killed trying to cross over to the working group.[16] Around 2,300 to 2,500 Jews from Dęblin—mainly the elderly and families with small children—were marched to the Dęblin train station (some 2.5 km (1.6 mi) away) at 18:00 and sent to Sobibór extermination camp.[16][20] The victims were beaten, and those who could not keep up were shot. Only late in the night were the Jews selected for labor allowed to return home. Every family was affected.[32] After the deportation, the bodies of the dead were collected at the synagogue and removed from the ghetto in carts.[14]

During the next two days, more than four thousand Jews from north Puławy County—200 from Bobrowniki (6 May), 1,800 from Ryki (7 May), 125 from Stężyca (7 May), 1,500 from Baranów (8 May) and 500 from Łysobyki (8 May)—were also marched to Dęblin and deported to Sobibór.[33] This was half of a countywide extermination action in Puławy County—the first in a series of systematic, countywide deportations in the Lublin District as part of Operation Reinhard. The county's administrator, Alfred Brandt ordered it shortly after Sobibór became operational; he was present in Dęblin during the deportation.[34][35]

Second deportation

| External image | |

|---|---|

The next deportation, which coincided with the liquidation of the two remaining ghettos in Puławy (Opole and Końskowola),[36][37] took place on 15 October 1942; the previous day, all workers had been ordered to remain at their workplaces. Under the command of SS-Obersturmführer Grossman, gendarmes, Luftwaffe soldiers, and police auxiliaries rounded up the remaining Jewish population.[16] Many Jews tried to avoid the roundup and enter the Luftwaffe camp, which at that time had 543 official residents. Some were turned away by the Jewish police there. Israeli historian Talia Farkash estimates that about 500, including 60–90 young children, managed to get in, mostly by paying bribes.[16][38] Silberklang's estimate is that 1,000 Jews entered the camp, including 280 women and 100 children.[27] The Jewish elder, Hermann Wenkert, later claimed that if he had allowed non-registered Jews entry, and they were discovered, everyone in the camp would have been killed. Instead, he bribed the Germans to obtain legal permits for an additional 400 Jews, which were mostly given to the wives and children of current residents.[38]

Many of the Slovak Jews, not knowing what to expect, had lingered in the ghetto while packing their bags. About 215 to 500 Jews were shot and killed by the Ukrainians and Germans while the houses were being cleared.[19][16] Between 2,000[19] and 2,500 people were deported to Treblinka extermination camp; mostly the Slovaks.[16][37] Members of the Judenrat, Jewish police, and their families, about 100 in total, were retained to clean up the ghetto.[8][16] Perhaps another 100 Jews were hiding without permission in the ghetto.[8] On 28 October, the remaining Jews were sent to the Schultz labor camp, and the ghetto was officially liquidated. Either on that day or within the next few weeks, 1,000 people were removed from the labor camps, including the 200 workers at Dęblin Fortress and 200 to 500 of the Luftwaffe's workers.[8][16] They were deported to Końskowola[8] or Treblinka.[16]

After this, Farkash estimates that there were about 1,400 Jews were still alive in the labor camps around Irena.[8] Estimates of the number at the Luftwaffe camp range from 1,000[16] to 2,000,[27] with another 300 at a railway camp near the passenger station, and 120 at another camp near the railway loading station.[8] During May or July 1943, most of the remaining prisoners in the railway camps were deported to Poniatowa concentration camp via the transit ghetto in Końskowola; the rest were deported in late 1943.[8][16] Hundreds of Jews were still alive in the remaining labor camps in Puławy County, but they were murdered during Operation Harvest Festival (2–3 November 1943). This operation also killed the prisoners of Poniatowa but did not affect the Jews at the Luftwaffe camp in Irena,[39][40] who were unaware of it.[41] Following Operation Harvest Festival, there were ten labor camps for Jews in the Lublin District with more than 10,000 Jews still alive.[42]

Luftwaffe camp

Camp leader

| External image | |

|---|---|

The camp leader (German: Lagerälteste) at the Luftwaffe camp was Hermann Wenkert, a Jewish lawyer from Vienna who had been deported to Opole in 1941 and came to Irena with the volunteers.[43] According to Wenkert's account,[40] soon after his arrival he happened upon Eduard Bromofsky, an Austrian Luftwaffe officer with whom Wenkert had served during World War I. Bromofsky convinced the commander of the camp to promote Wenkert to his position. Even after Bromofsky was reassigned, the relationships that Wenkert had cultivated with the German authorities enabled him to retain his position.[43] Wenkert populated the administration with other Viennese Jews, insisted on extra rations for himself and his family, and had his family transferred from Opole to Irena. Because of his close association with the German authorities and use of his position for personal benefit, some survivors considered him to be a collaborator.[43][44] When it was possible, Wenkert negotiated with the authorities and paid bribes to avoid punishment; he also consulted respected prisoners in cases where the matter had not come to German attention. However, when he thought there was no other option and the survival of the camp was in the balance, Wenkert turned Jews accused of wrongdoing over to the Germans even though he knew that this would result in their deaths.[45] In general, German-speaking Jews had a more positive impression of him than the local Jews, who spoke Yiddish.[46] According to Silberklang, both views of Wenkert may be true: that he tried to secure benefits for himself personally while also working to keep the other Jewish prisoners alive.[47]

Conditions

Conditions were relatively good compared to other camps.[42][48] Residents received food rations of about 1,700 kilocalories daily (enough to live), weekly baths, and medical care, and were allowed to practice their religion.[27][49] The presence of 100 young children—whose existence was justified as increasing the productivity of their parents—was particularly unusual and not matched elsewhere in the Lublin District after Operation Harvest Festival. Aida Milgroijm-Citronbojm continued the Polish-language school that she had run in the ghetto. The SS, who did not know about the children's existence, periodically conducted surprise inspections of the camp, during which the children had to hide.[50] According to Farkash, Wenkert's positive relationship with the camp command was partially responsible for the good conditions.[51] Wenkert managed to get religious Jews exempted from working on Shabbat and allowed a chevra kadisha society to operate, burying the dead according to Jewish law. In 1943, about 80 Jews (including Wenkert) received kosher food for the week of Passover.[44][52]

The camp had three German commanders, all at the rank of sergeant major: Kattengel (through March 1943), Dusy, and Rademacher (during the last two months). Although Kattengel was distrusted because he roamed the camp with a dog and whip, both Dusy and Rademacher were described positively by survivors. Dusy even arranged for one woman to receive treatment at a German hospital after she was badly injured. Wiszniewski, a local Volksdeutscher, was the lead foreman of the Jewish laborers and did not mistreat them. Autheried engineer Kozak brought food to the Jews he worked with.[53] The Slovak Jews at the camp were the last major group to survive of the almost 40,000 Slovak Jews deported to the Lublin District in 1942.[54][55] The Jews remaining in Prešov hired couriers (non-Jews from the Polish–Slovak border) to travel to the camp regularly until it was dissolved, carrying letters and bringing valuables and money. A committee was formed in the camp to distribute these among the Slovak Jews. Cases of theft by Polish Jews led to friction between the two communities.[56][54]

Despite the relatively good conditions, some Jews tried to escape because they feared that the camp would be liquidated. The Luftwaffe camp command imposed collective punishment to deter escapees. Both theft and possessing foreign currency were punishable by hanging. Punishment could be excessive and arbitrary—nine Jews were executed by firing squad for causing an accidental fire—but less so than other Nazi camps.[57] Reports of the Home Army from that time often described the local ethnic Polish population as hostile to "Jewish bands" which stole food and resources from Polish peasants; said reports, according to Zimmerman, therefore can be seen as reflecting "the eerie distance of mere observers".[58] According to Farkash, in 1943, Wenkert allowed a group of Jewish partisans seeking refuge from a hostile unit of the Polish Home Army resistance group into the camp.[45] Most Jews who tried to escape were captured, and others returned to the camp.[59] Several members of the Kowalczyk peasant family were honored as Righteous Among the Nations for sheltering nine Jews who had escaped from the Łuków ghetto and the Dęblin camp on their farm in Rozłąki, from late 1943 to mid-1944.[60] Árpád Szabó, a Hungarian military doctor, was similarly recognized for smuggling a Slovak Jewish couple from the camp to Hungary.[61]

Liquidation

The camp was liquidated on 22 July 1944, the same day that the Red Army reached Lublin.[16] At the time of the deportation, some 800 to 900 Jews were still alive, of whom 400 to 600 were from Dęblin or Irena,[16] 40 from Vienna,[56] and 70 to 80 from Slovakia.[54] Two[62] or three[41] transports departed from Irena on 17 and 22 July. (Silberklang reports a third on 20 July).[41] Since no one was willing to volunteer, the first transport carried about 200 people who had few connections in the camp, including single adults and fifteen children between three and six years of age. On the orders of camp security officer Georg Bartenschlager, the fifteen children were shot and killed upon their arrival in Częstochowa. The rest of the prisoners, including Wenkert and 33 young children, departed on the second transport with Rademacher, the German camp commander, who carried a letter of protection from the airfield commander.[62] About fifty Jews escaped from the camp during the evacuation, but most were killed. The second transport arrived in Częstochowa on 25 July; the young children were kept separated for two and a half days but were not killed. The reason for this is not clear, but likely involved negotiations with Bartenschlager.[63] In Częstochowa, the Jews worked at the four Hugo Schneider AG plants. Some were deported to Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen in January 1945 while others were liberated by the Red Army.[64] About half survived.[16]

According to Farkash, the airfield camp in Irena is a "singular case" in the Lublin district and possibly in the entirety of occupied Poland.[65] One unusual aspect of the camp was that it was run from start to finish by the Luftwaffe rather than the SS, although during 1943 and 1944, the SS tried to expand its role.[66] According to Silberklang, being run by the Wehrmacht helped to ensure the camp's survival.[67] However, other camps (such as three in Zamość county) were run by the Luftwaffe and were still liquidated before the end of 1943.[68] Another reason was the importance of Jewish workers at Dęblin to the German war effort,[69][70] which was continually emphasized by Wenkert in his dealings with the Germans. Overall, luck played a major role in the fortuitous combination of Jewish leadership, relatively friendly Germans, and the evacuation of the camp to Częstochowa rather than Auschwitz-Birkenau.[70] Ninety-nine percent of the Jews from Lublin District were killed in the Holocaust,[71] but hundreds from Dęblin and Irena survived the war.[70]

Aftermath

Dęblin was liberated by the 1st Polish Army by 27 July 1944.[72] In 1945, Alfred Brandt was convicted and sentenced to death for his crimes by a Soviet military tribunal near Słupsk and executed by firing squad.[73] Some of the Jewish survivors, who attempted to return home in January 1945, were told by the local Milicja Obywatelska police chief that it was illegal for them to settle in the town.[74][75][76] In March 1945, survivors Łaja, Gitla and Fryda Luksemburg were murdered with the involvement of local police.[77][78] Other Jews received threatening letters.[78] Following the 1946 Kielce pogrom, a meeting in Dęblin was held to commemorate the victims. Locals interrupted the meeting with anti-semitic slogans.[79] By 1947, no Jews remained in the town,[78] which is still the case in the twenty-first century.[4] As of 2011, the Dęblin Synagogue was in poor condition and being considered for demolition.[80] A memorial plaque about the Irena ghetto was unveiled in Dęblin in 2015.[78]

Ignaz Bubis, a former prisoner of the ghetto,[8][16] was the chairman of the Central Council of Jews in Germany from 1992 to 1999.[81]

Notes

References

Citations

- ↑ Aronson & Longerich 2001, p. 194.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Crago 2012b, p. 636.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Yad Vashem 2009, p. 156.

- 1 2 3 "Deblin Modrzyc (Irena)". Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ Rubin 2006, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Rubin 2006, p. 90.

- ↑ Protassewicz 2019, p. 210.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Farkash 2014, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 Rubin 2006, p. 91.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Crago 2012b, p. 637.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 Yad Vashem 2009, p. 157.

- 1 2 3 Rubin 2006, p. 92.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Crago 2012b, p. 638.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, p. 196.

- ↑ Büchler 1991, p. 166.

- 1 2 3 Farkash 2014, p. 62.

- 1 2 3 Farkash 2014, p. 61.

- 1 2 Snyder 2012, p. 180.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, pp. 274, 399.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, pp. 399–400.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, p. 274.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 61, 70.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Farkash 2014, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 4 Silberklang 2013, p. 400.

- ↑ Weinstein 2006, p. 459.

- ↑ Musiał 2000, p. 244.

- ↑ Crago 2012a, p. 608.

- ↑ Yad Vashem 2009, p. 158.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, pp. 308, 317.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, p. 309.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, p. 60.

- 1 2 Silberklang 2013, p. 329.

- 1 2 Farkash 2014, p. 66.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 60–61, 63.

- 1 2 Silberklang 2013, p. 402.

- 1 2 3 Silberklang 2013, p. 409.

- 1 2 Silberklang 2013, p. 365.

- 1 2 3 Farkash 2014, p. 65.

- 1 2 Silberklang 2013, p. 401.

- 1 2 Farkash 2014, p. 67.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, p. 66.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, pp. 401–402.

- ↑ Rubin 2006, p. 93.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, p. 78.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, p. 69.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 69–70.

- 1 2 3 Büchler 1991, p. 159.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, p. 296.

- 1 2 Farkash 2014, p. 70.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Zimmerman 2015, pp. 213, 361.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, p. 74.

- ↑ "Kowalczyk family". The Righteous Among the Nations Database. Yad Vashem. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ↑ "Szabó Árpád". The Righteous Among the Nations Database. Yad Vashem. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- 1 2 Farkash 2014, p. 75.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, p. 77.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, p. 58.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, p. 68.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, p. 364.

- ↑ Farkash 2014, pp. 68, 78.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, p. 411.

- 1 2 3 Farkash 2014, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Silberklang 2013, p. 431.

- ↑ Weinstein 2006, p. 536.

- ↑ Schmeitzner et al. 2015, p. 67.

- ↑ Kopciowski 2008, p. 202.

- ↑ Rice 2017, p. 29.

- ↑ Koźmińska-Frejlak 2014, p. 154.

- ↑ Krzyżanowski 2013, p. 253.

- 1 2 3 4 "Odsłonięcie tablicy pamiątkowej" [Unveiling of a commemorative plaque]. Miasto Dęblin (in Polish). 27 October 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ↑ Krzyżanowski 2020, p. 125.

- ↑ Bergman & Jagielski 2014, p. 565.

- ↑ Friedlander, Albert (16 August 1999). "Obituary: Ignatz Bubis". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

Sources

- Aronson, Shlomo; Longerich, Peter (2001). "Final Solution: Preparation and Implementation". In Laqueur, Walter; Baumel, Judith Tydor (eds.). Holocaust Encyclopedia. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 184–198. ISBN 978-0-300-08432-0.

- Bergman, Eleonora; Jagielski, Jan (2014) [2011]. "Traces of Jewish Presence: Synagogues and Cemeteries from 1944 to 1997". In Tych, Feliks; Adamczyk-Garbowska, Monika (eds.). Jewish Presence in Absence: the Aftermath of the Holocaust in Poland, 1944–2010 (PDF). Translated by Dąbkowski, Grzegorz; Taylor-Kucia, Jessica. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. pp. 541–566. ISBN 978-965-308-449-0.

- Büchler, Yehoshua (1991). "The deportation of Slovakian Jews to the Lublin District of Poland in 1942". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 6 (2): 151–166. doi:10.1093/hgs/6.2.151. ISSN 8756-6583.

- Crago, Laura (2012a). "Lublin Region (Distrikt Lublin)". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 604–609. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Crago, Laura (2012b). "Irena (Dęblin–Irena)". In Geoffrey P., Megargee; Dean, Martin (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 636–639. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- Farkash, Talia (2014). "Labor and Extermination: The Labor Camp at the Dęblin-Irena Airfield Puławy County, Lublin Province, Poland – 1942–1944". Dapim: Studies on the Holocaust. 29 (1): 58–79. doi:10.1080/23256249.2014.987989.

- Kopciowski, Adam (2008). "Anti-Jewish Incidents in the Lublin Region in the Early Years after World War II". Zagłada Żydów. Studia i Materiały: 177–205. doi:10.32927/ZZSiM.80. ISSN 2657-3571.

- Koźmińska-Frejlak, Ewa (2014) [2011]. "The Adaptation of Survivors to the Post-War Reality from 1944 to 1949". In Tych, Feliks; Adamczyk-Garbowska, Monika (eds.). Jewish Presence in Absence: the Aftermath of the Holocaust in Poland, 1944–2010 (PDF). Translated by Dąbkowski, Grzegorz; Taylor-Kucia, Jessica. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. pp. 125–164. ISBN 978-965-308-449-0.

- Krzyżanowski, Łukasz (2013). "Homecomers: Jews and Non-Jews in Post-War Radom". Kwartalnik Historii Żydów. 246 (2): 248–256. ISSN 1899-3044. CEEOL 270613.

- Krzyżanowski, Łukasz (2020). Ghost Citizens: Jewish Return to a Postwar City. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-98466-0.

- Musiał, Bogdan (2000). Deutsche Zivilverwaltung und Judenverfolgung im Generalgouvernement: eine Fallstudie zum Distrikt Lublin 1939–1944 [German Civil Administration and the Persecution of Jews in the General Government: a Case Study on the Lublin District 1939–1944] (in German). Leipzig: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05063-0.

- Protassewicz, Irena (2019). A Polish Woman's Experience in World War II: Conflict, Deportation and Exile. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-07993-9.

- Rice, Monika (2017). What! Still Alive?!: Jewish Survivors in Poland and Israel Remember Homecoming. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-5419-3.

- Rubin, Arnon (2006) [1999]. "Dęblin–Irena". District Lublin. The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Communities in Poland and their Relics Today. Vol. 2. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University Press. pp. 89–93. ISBN 978-965-90744-2-6.

- Schmeitzner, Mike; Weigelt, Andreas; Müller, Klaus-Dieter; Schaarschmidt, Thomas (2015). Todesurteile sowjetischer Militärtribunale gegen Deutsche (1944–1947): Eine historisch-biographische Studie [Soviet military tribunals' death sentences against Germans (1944–1947): A historical-biographical study] (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-647-36968-6.

- Silberklang, David (2013). Gates of Tears: the Holocaust in the Lublin District. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. ISBN 978-965-308-464-3.

- Snyder, Timothy D. (2012). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-03297-6.

- Weinstein, Frederick (2006). Schieb, Barbara; Voigt, Martina (eds.). Aufzeichnungen aus dem Versteck: Erlebnisse eines polnischen Juden 1939–1946 [Notes from Hiding: Experiences of a Polish Jew 1939–1946] (in German). Berlin: Lukas Verlag. ISBN 978-3-936872-70-5. Secondhand account of first deportation on pages 206–208.

- Miron, Gai; Shulhani, Shlomit, eds. (2009). "Dęblin–Irena". The Yad Vashem Encyclopedia of the Ghettos During the Holocaust. Vol. 1. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem. pp. 156–158. ISBN 978-965-308-345-5.

- Zimmerman, Joshua D. (2015). The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01426-8.

Further reading

- Stokfish, David, ed. (2003) [1969]. Sefer Deblin-Modzjitz [Deblin-Modzjitz Yizkor Book]. Translated by Altman, Nolan. Tel Aviv: Arazi. ISBN 978-0-657-14368-8.

- Wenkart, Hermann (2013) [1969]. Befehlsnotstand anders gesehen: Tatsachenbericht eines jüdischen Lagerfunktionärs [An Alternate View of Befehlsnotstand: Factual Report of a Jewish Camp Functionary] (in German). Norderstedt, Hamburg: Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-7322-4754-7.

External links

- Video and audio testimonies from Poles and Jews who lived in Dęblin during the war (English, Polish, Hebrew)