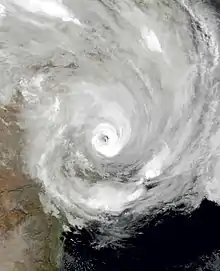

Eloise nearing landfall in Mozambique at peak intensity on 22 January 2021 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 15 January 2021 |

| Remnant low | 26 January 2021 |

| Dissipated | 27 January 2021 |

| Tropical cyclone | |

| 10-minute sustained (MFR) | |

| Highest winds | 150 km/h (90 mph) |

| Highest gusts | 215 km/h (130 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 967 hPa (mbar); 28.56 inHg |

| Category 2-equivalent tropical cyclone | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 165 km/h (105 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 968 hPa (mbar); 28.59 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 27 |

| Missing | 11 |

| Damage | >$10 million (2021 USD) |

| Areas affected | Madagascar, Mozambique, Malawi, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Eswatini |

| IBTrACS / [1] | |

Part of the 2020–21 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season | |

Tropical Cyclone Eloise was the strongest tropical cyclone to impact the country of Mozambique since Cyclone Kenneth in 2019 and the second of three consecutive tropical cyclones to impact Mozambique in the 2020–21 South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season. The seventh tropical depression, fifth named storm and the second tropical cyclone of the season, Eloise's origins can be traced to a disturbance over the central portion of the South-West Indian Ocean basin which developed into a tropical depression on 16 January, and strengthened into a tropical storm on 17 January, though the storm had limited strength and organization. On the next day, the storm entered a more favorable environment, and it soon intensified to a severe tropical storm on 18 January. Late on 19 January, Eloise made landfall in northern Madagascar as a moderate tropical storm, bringing with it heavy rainfall and flooding. The storm traversed Madagascar and entered the Mozambique Channel in the early hours of 21 January. After moving southwestward across the Mozambique Channel for an additional 2 days, Eloise strengthened into a Category 1-equivalent cyclone, due to low wind shear and high sea surface temperatures. Early on 23 January, Eloise peaked as a Category 2-equivalent tropical cyclone on the Saffir–Simpson scale as the center of the storm began to move ashore in Mozambique. Shortly afterward, Eloise made landfall just north of Beira, Mozambique, before rapidly weakening. Subsequently, Eloise weakened into a remnant low over land on 25 January, dissipating soon afterward.

Preparations for the advancing storm took place in Madagascar before Eloise's landfall and in multiple other African countries. For Madagascar, widespread warnings and alerts were issued as the storm approached northern Madagascar. For Mozambique, high alerts were put in place for central portions of the country. Humanitarian responders prepared for response after the storms passing. Beira's port also closed for about 40 hours, and limited supplies of emergency non-food items were given. Many families were sheltered in tents at accommodation centers, and received kits for food, hygiene, and COVID-19 protection. Officials in Zimbabwe warned of ravine and flash flooding, which may cause infrastructure damage. Several northern provinces of South Africa were expected to experience heavy rains, which prompted severe risk warnings for them. Disaster management teams were placed on high alert ahead of the storm.

Extreme flooding occurred throughout central Mozambique, with many areas being flooded due to continuous heavy rains weeks prior to Eloise's landfall. More than 100,000 people have been displaced and dams are at a tipping point. Infrastructure has taken a heavy hit. Approximately 100,000 people were evacuated by 23 January, although the number is expected to grow to 400,000. Flooding and damage have been less than feared.[2] Weak shelters set up for the cyclone were either damaged or destroyed. Beira was completely flooded, and the impacts were comparable to those of Cyclone Idai, though they were far less severe. Farmland was damaged as well. Teams were sent out to assess the damage and repair it. There have been 27 confirmed deaths, with one in Madagascar, 11 in Mozambique, three in Zimbabwe, 10 in South Africa, and two in Eswatini.[3][4][5][6][7][8] Eleven additional people are currently missing.[8][9][6][10] Current damage from the storm is estimated to exceed $10 million (2021 USD) in Southern Africa.[11]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On 14 January, a zone of disturbed weather formed over the central South Indian Ocean to the east of another system and gradually organized while moving westward.[12] On 16 January, the system organized into a tropical depression.[13] With the presence of persisting deep convection, the system eventually strengthened into Moderate Tropical Storm Eloise on 17 January.[14] Initially, Eloise struggled to strengthen further from the presence of strong easterly shear and dry air, which caused Eloise's thunderstorm activity to be displaced to the west.[15] Despite the presence of this shear and mid-level dry air, Eloise continued to intensify, with convection wrapping into an eye feature and outflow becoming increasingly defined, marking the intensification of Eloise into a severe tropical storm on 19 January, while heading westward towards Madagascar.[16]

This intensification trend did not last for a long time, as Eloise made a small turn to the north and then made landfall in Antalaha, Madagascar, whilst weakening back to a moderate tropical storm, due to land interaction with the mountains of Madagascar.[17] The next day, Eloise weakened to a tropical depression due to land interaction, with deep convection over its center eroded though it maintained flaring convection over the northern semicircle.[18]

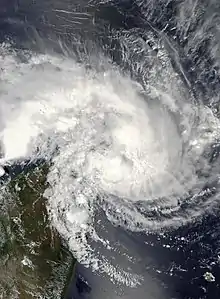

On 20 January, Eloise emerged into the Mozambique Channel, where Eloise began to slowly reintensify, with warm waters, a moist environment, little shear, but weak upper-level divergence contributing to the storm's slow strengthening trend.[19] However, some upper-level convergence hindered convection from developing quickly, though all other factors were relatively favorable.[20] Soon afterward, the upper-level convergence began to decrease, allowing the system to begin rapidly strengthening.[21] On 21 January, Eloise's outflow became robust, though its strength was limited, due to land interaction in the northern semicircle of the storm, having the strongest winds in the southeast quadrant and sustaining much weaker winds elsewhere. Despite sustained land interaction, Eloise strengthened, with improving poleward outflow and tightly wrapped banding features wrapping into an small eye.[22]

On 22 January, Eloise significantly improved in organization as it moved southwestward across the Mozambique Channel. Later that day, Eloise strengthened into a Category 1-equivalent tropical cyclone on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale (SSHWS), as it neared the coast of Mozambique, given the favorable conditions in the region. Early on 23 January, Eloise strengthened further and peaked as a Category 2-equivalent tropical cyclone, with 10-minute sustained winds of 150 km/h (95 mph), 1-minute sustained winds of 165 km/h (105 mph), and a minimum central pressure of 967 millibars (28.6 inHg), as the storm's eyewall began moving ashore. Soon afterward, Eloise made landfall just north of Beira, Mozambique, at the same intensity.[23][24] Following landfall, Eloise rapidly deteriorated, with the storm weakening back into a moderate tropical storm within 12 hours and the eye completely disappearing.[25] As the storm moved further inland, Eloise weakened rapidly, due to interaction with the rugged terrain and dry air.[26] Later that day, Eloise weakened into a tropical depression as it tracked further inland.[27] On 25 January, Eloise degenerated into a remnant low, and the MFR issued their final advisory on the system, with the storm dissipating soon afterward.[28]

Preparations

Madagascar

Ahead of landfall, humanitarians and authorities in Madagascar coordinated preparedness activities. A meeting was organized on 19 January by the National Office for Risk and Disaster Management (BNGRC) to prepare for potential assessments and/or response. Authorities devised plans, including contingency plans, evacuation plans, emergency operation centres and early warning system at the community level. Aerial assessments using photo and geo-tracking system were also planned for the impact of the storm.[29] The local contingency plan in the north-eastern part of the country and the early warning system at the community level was activated. Emergency stocks are available in many districts in the most at-risk areas.[30] On 18 January, the Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System (GDACS) gave the storm a green alert, which pointed to a wind impact of 0.5. The next day, GDACS upgraded the storm alert to an orange alert, which pointed to a higher 1.5 wind impact.[31][32][33] With Eloise enhancing heavy rainfall, landslides, flash floods, and widespread flooding were expected.[34] Moreover, waves up 6 m (20 ft) were expected in Antongil Bay.[35]

Mozambique

According to the Mozambican National Meteorological Institute (INAM), Eloise was expected to make landfall somewhere between the Inhambane and Gaza provinces.[36] Government officials have placed the Inhanombe and Mutamba in southern Mozambique and Buzi and Pungoe basins in central Mozambique on high alert.[36] The newly created National Institute for Management and Disaster Risk Reduction (INGD) – which has replaced the former National Disaster Management Institute (INGC) – closely followed Eloise's trajectory and worked with humanitarian partners to prepare for any response required.[37] By mid-afternoon 22 January, shops across Beira were closed and multiple streets were flooded from rainfall brought by the approaching storm. The port of Beira will closed for about 40 hours, in expectation of dangerous winds and flooding rains. A limited supply of emergency items had been stockpiled in the city. Hundreds of families were evacuation to two accommodation centers and are sheltered in tents. People in shelters are in need of food and hygiene kits, as well as COVID-19 protection.[38] Mozambique's National Institute for Disaster Risk Management and Reduction (INGD) reported that around 3,000 people were evacuated from Buzi District.[39]

South Africa

According to the South African Weather Service, Northern Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and northern KwaZulu are expected to be affected by heavy rains that may last into Monday. The South African Weather Service (SAWS) had put a level 4 yellow and a level 9 orange warning through 25 January for disruptive rain across central and eastern parts of the Mpumulanga and Limpopo provinces and the northeastern parts of Kwazulu-Natal Province. The Meteorological Services Department of Zimbabwe had warned of heavy rainfall, flooding, destructive winds and lightning on 23 January in parts of the country due to Tropical Cyclone Eloise.[40] Widespread flooding, and water-related damage to infrastructure was expected. Sipho Hlomuka, a co-operative governance and traditional affairs for KwaZulu-Natal, had placed disaster management teams on high alert.[41] Disaster management teams were put on high alert in Limpopo ahead of the cyclones expected impacts in the region.[42]

Alert nines were issued for Limpopo and Mpumalanga. Basikopo Makamu, Limpopo's Cooperative Governance MEC, said the SANDF were on standby to help rescue people who may be cut off or trapped due to Eloise.[43] The Gauteng emergency response team is on alert. They have activated contingency plans, to assist Gauteng and other surrounding provinces.[44] SAWS has issued red alerts for disruptive rains over Lowveld areas of Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces as well as the eastern Highveld areas. These will persist until 25 January. The weather service warned that rainfall may add to saturated grounds and worsen potential flooding, mudslides, and rockfalls. These may disrupt essential services, like food, water, sanitation, electricity, and communication.[45] On 27 January, SAWS issued warnings for disruptive landfall from 26 January to 29 January. This included a yellow warning for western North-West province and extreme north-eastern portions of Northern Cape. These spread to western and central Free State.[46]

Elsewhere

In Eswatini, the National Disaster Management Agency (NDMA) determined that northern and eastern part of the country might be vulnerable to Cyclone Eloise, with high altitude areas of high focus. Early warning systems were initiated, and evacuation plans to evacuation centers were prepared, in addition to other necessary measures.[47] The Municipal Council of Mbabane Public Information states that drains had been cleaned out to avoid floods and that trees that threatened structures and people were identified.[48] The Royal Eswatini Police Service urged motorists to be cautious, and to abide by an 8 PM to 4 AM curfew.[49]

Both the Department of Climate Change and Meteorological Services in Malawi and Mozambique noted that Malawi would be unlikely to be directly impacted by Eloise, but would experience some rainfall.[50][51] Furthermore, officials issued warnings for heavy downpours and strong winds.[52] In Botswana, the government's Meteorological Services issued a warning for heavy rains, strong winds, and localized flooding on 24 January. On 22 January, the service informed that the remnants of Eloise were expected to cause heavy rainfall, strong winds, and lightning. They advised the population to take caution.[45]

Impact

Madagascar

On 19 January, Eloise made landfall in the northeastern town of Antalaha, Madagascar as a tropical storm. Eloise produced heavy rain, which had the potential to lead to floods and landslides in northern Madagascar.[29] Météo-France noted on 20 January that accumulations for 100–150 mm (3.9–5.9 in) were possible in 24 hours for the northwestern regions of Madagascar.[53] By 18:00 UTC on 19 January, authorities had issued a red alert (imminent danger) for the Sava, Analanjirofo, Bealanana, Befandriana Avaratra and Mandritsara regions and a yellow alert (threat) for Toamasina I-II and Alaotra. All weather warnings have been lifted in Brickaville, Vatomandry, Mahanoro and Moramanga.[36] Strong winds, reaching near gale force (64 km/h (40 mph)) spread from north to south along the northwestern coast of Madagascar.[53] While passing through Madagascar, Eloise enhanced some monsoon winds, generating rainfall up to 200 mm (7.9 in) in some places.[39]

Roughly 190 homes were either damaged or destroyed by the storm.[54] Eloise exited Madagascar on 21 January, leaving one person dead in the country.[39][3]

Mozambique

"When I went outside, there was water everywhere – up to my knees – and trees, electrical wires, roof tiles, and fences all destroyed, strewn about on the streets. Thank God it has stopped raining. I never thought I would be afraid of water, but this was horrible,"

Chris Neeson, UN of Beira[55]

Merely weeks after Tropical Storm Chalane made landfall in the country, Eloise made landfall around 2:30 a.m. CAT with wind speeds of 160 km/h (100 mph). Due to flooding, cars were submerged in water; walls of some low lying buildings collapsed and swathes of land were flooded in Beira, while the power supply was shut down as Eloise damaged power lines and uprooted some electricity poles, power utility EDM noted.[56]

IOM Mozambique also reported that due to heavy rainfall and discharge of water from the Chicamba dam and the Manuzi Reservoir, 19,000 people were affected in that area. Cyclones cause major flooding, which can drown animals and destroy their natural environments. When smaller animals and food supplies disappear or get killed, it affects larger animals because they can no longer find enough food.[57]

At least eleven people died in the country.[7] Since beginning of heavy rains on 15 January, 21,500 people were affected and over 3,900 acres of farmland was damaged or destroyed. According to preliminary satellite analysis by UNOSAT surveying the Sofala and Manica provinces, about 2,200 km2 of land appeared to be flooded, with Beira City, Buzi and Nhamatanda had the greatest number of people potentially exposed to flooding.[58] Furthermore, the rainfall affected 100,000 in Beira resettlement sites, which had been impacted by Cyclone Idai a year ago and Tropical Storm Chalane only a couple weeks before.[38] Temporary shelters such as tents and homes made from plastic sheeting were heavily destroyed by Eloise.[59] Some of the worst-hit areas, such as the Buzi District, outside of Beira, were already submerged by days of heavy rains ahead of the cyclone's landfall, with floodwaters consuming fields and flowing through village streets.[39] Large trees were uprooted and the entirety of Beira was covered by water by 23 January, while communication was eventually cut off.[60] Residents compared the impacts of the cyclone largely to that of Idai in 2019.[61] Prior to landfall, 4,000 households were affected by floods in Buzi, with another 266 in Nhamatanda, and 326 in Beira. The provinces of Inhambane, Manica, Niassa, Sofala, Tete, and Zambezia had already received between 200–300 mm (7.9–11.8 in) of rain since 9 January. This was worsened after Eloise made landfall. Dams were brought to a tipping point, which raised concerns that they may worsen the flooding even more for the affected areas.[62] Advertising hoardings were blown over due to wind, and rivers burst through their banks in the region. The locals also expressed fear of losing crops, as floodwaters either damaged or destroyed farmland.[55]

More than 5,000 homes in total were damaged across Buzi, Dondo, Nhamatanda, and Beira City, according to the government's preliminary data. Specifically, 1,069 were destroyed, 3,343 were damaged, and over 1,500 were flooded. Dozens of classrooms were damaged or destroyed, and at least 26[63] health centers were damaged. At least 177,000 hectares[64] of crops have been flooded, such as maize, rice, cassava, and others[9] (these numbers may rise after more data is collected).[45] Roads were rendered impassable in parts of the Sofala, Zambezi, Inhumane, and Manica Provinces. The amount of those affected in the country rose to 163,283 on 25 January, including 6,859 displaced. Assessments indicated that Sofala Province was the hardest hit, especially in the Buzi, Dondo, and Nhamatanda districts, as well as Beira City.[45]

Due to the psychological effects of Idai's impact still persisting, mental support for the people affected was critical.[45] The storm displaced at least 8,000 individuals across the country.[3] Some humanitarian facilities were damaged.[9] Farm tools and seeds were destroyed.[63] On 27 January, an estimated 74 health centers and 322 classrooms were damaged or destroyed.[65] On 28 January, the number of houses affected rose to a total of 20,558. 6,297 were destroyed, 11,254 were damaged, and 3,007 were flooded.[64] The number climbed to 29,310 houses, with 17,738 destroyed, 8,565 damaged, and 3,007 flooded. The number kept rising for classrooms and health centers; with 579 and 86 in need of repairs respectively.[66]

South Africa

Due to persistent heavy rain, low-lying areas of Limpopo had seen mild flooding and debris which caused some roads to close. The Mufongodi and Luvhuvu river overflowed its banks. Strong winds knocked down trees. However, the eThekwini and uMgungundlovu district municipalities experienced only light rainfall. Disaster management teams reported that KwaZulu-Natal settlements, such as Jozini, were already experiencing flooding. Julius Mahlangu, a forecaster for the SAWS, said that the rains were expected to cease by Monday morning.[67] Kruger National Park closed multiple roads and camps as the cyclone passed over. Rivers in the park overflowed. Previously evacuated Bushveld camps were left inaccessible. There were sporadic reports of damaged houses and infrastructure. The Gert Sibande and Dr Pixley Ka Isaka Seme areas also saw heavy rainfall. Dams were also having their water levels be monitored for potential tipping points,[68] and the Albasini dam had to open its flood gates.[69]

A five-year-old child in the eastern Mpumalunga Province was killed after he was swept away by floodwaters,[3] as well as a fourteen-year-old boy who drowned in KwaZulu-Natal.[6] Bridges and vehicles were submerged in affected areas as well; the Vhembe District being the worst affected. The province received 150mm of rain in less than 16 hours.[49] After a two-day operation, Rescue SA uncovered the body of a 35-year-old man who had drowned in the Blyde River. A mother and baby were swept away while crossing a flooded river in Elukwatini, and a one year old drowned. Eastern Cape, Free State, Gauteng and Northern Cape all experienced higher rainfall than in 2020, according to a report released by AfriWX. Steven Vermaak, chairman of the Transvaal Land Union of water affairs, said that the Nyl river, in Limpopo, ran for the first time in 15 years.[6] On 12 February, in a public government gazette, a national state of disaster was declared as damage had been more serious than previously thought.[70] At least 10 people in South Africa were killed by devastating floods brought by Eloise, while another 7 people were reported to be missing.[8]

Zimbabwe

Flooding occurred in Zimbabwe, damaging homes and property. The country's civil protection unit reported that 3 people had been swept away, who were presumed dead. Affected parts of the country had also been badly struck by Idai in 2019. Schools were damaged in Chimanimani and Chipinge districts. Communities near the Save River moved to higher ground due to the water level rising. The Manyuchi and Tugwi Mukosi dams started overflowing, and downstream areas have been placed on high alert.[5] Rains also caused a mudslide in Chipinge and Tanganda, with large boulders blocking some roads. These also damaged at least three schools across the province. The Watershed, Bangazzan, and Mutakura dams were at near-flooding levels. In Masvingo Province, damages to roads have hampered access to almost 170 people waiting to be evacuated in Ward 34 of Village 21. Some other people were also in need of shelter and assistance. In Harare, Zimbabwe's capital, 34 families were evacuated to two high schools in Budiriro, and were in need of emergency supplies.[45] Mudslides also occurred in Manicaland, Mashonaland East, Mashonaland Central, Matabeleland South and Masvingo provinces.[49]

Over 400 households had been damaged or destroyed in the Masvingo province. The IOM reported that dams in Gutu District had reached full capacity and there was a risk of flooding.[46] As of 28 January, 349 houses have been reported to be either damaged or destroyed. In Chipinge, 190 households were affected across 7 wards.[64]

Elsewhere

In Eswatini, the storm was reported to have killed two people.[3] The country had most of its rivers flooded, and several areas are affected.[49] Gravel roads and low-lying bridges have been washed out by rains. The Mncitsini, Manzana, Mangwaneni, Mpolonjeni provinces all reported mudslides and landslides. Over 1,500 people have been affected in the country. Water supply systems were damaged.[9]

Aftermath

Mozambique

Teams were sent out on 23 January to assess damage on transmission lines and pylons, and to figure out repair. President Filipe Nyusi set to travel to affected areas. The UNFPA delivered seven tents to serve as temporary health centers, as well as woman-friendly spaces. They are also on standby to give out 500 dignity kits containing essential items for vulnerable women and girls. They are also focusing on responses to help mitigate gender-based violence.[61] At least 8,000 people were said to be displaced at the time.[3] Over 20 accommodation centers were opened for people to take shelter in.[71] This number then rose to 32.[63] IFRC Africa sent out nearly 360,000 swiss francs for a disaster relief fund to help affected families.[72]

Nine Accommodation centres activated in Dondo and Muasa districts were deactivated by INGD. Food, tents, potable water, hygiene kits, and many other items were in critical need as the storm passed.[73][74] As many as 10 people were living inside of some emergency tents at one time. Over 8,700 people were living in 16 temporary shelters in the port of Beira, due to Eloise's damages. The United Kingdoms foreign office said on 26 January that they would donate £1 million ($1.37 million) to help aid Mozambique's recovery. They also sent out a team of relief workers to assess damage and humanitarian needs.[74] The number of those affected were at 248,481 with 16,693 displaced, according to data released by the INGD, along with a total of 17,000 houses.[9] Flooding in the lower Limpopo river basin in the country was expected to peak around 26 or 27 January, according to the FCDO.[9] IOM provided soap and limited amounts of cloth face masks to the most vulnerable. They also attempted to give out information regarding to social distancing, but circumstances at the time proved it to be difficult.[63] Prime Minister Carlos Carlos Agostinho do Rosário visited the Sofala province on 25 January, and called on local residing in areas at risk of even more flooding to evacuate to safer grounds.[75] More than 90,000 children were affected.[6] Psychosocial support were also of high importance.[76] UNICEF handed out prepositioned basic household and hygiene items, water purification products, and tarpaulin sheets for up to 20,000 people.[65]

On 29 January, the international aid organization Food for Hungry (FN) announced details of its response in Mozambique. It covered the districts Nhamatanda, Beira, and Dondo in the province of Sofala, and planned to serve 2,200 households immediately. They distributed much needed supplies for survivors, staff, and volunteers. FH's Mozambique Country Director, Judy Atoni, said they will be working with peer organizations to develop and implement long term humanitarian aid.[77] According to more preliminary data released by INGD on 28 January, the number of people affected still continued to rise as teams continued to survey damage, with the number standing at 314,369; a significant increase was reported in Buzi District. At least 20,012 people were still seeking shelter in 31 temporary accommodation shelters at the time (30 in Sofala, 1 in Inhambane). This was a slight decrease from 27 January, where 32 centers held 20,167 people.[66]

GBV partners (UNFPA, Plan Int'l, IsraAid) distributed 782 dignity kits to evacuated and/or displaced women. A referral mechanism was put in place for urgent protection. The flooding in and around Buzi was comparable to an open sea.[78] Some people tried building shelter after Idai in 2019 and have had their attempts damaged or destroyed. Oxfam called for international support immediately on 2 February, saying that any delay of any size could have disastrous consequences. At the time, they needed $3 million to provide clean water, sanitation, and hygiene support to 52,600 people in affected areas. They estimated over 260,000 people were in critical need of humanitarian aid.[79] Protection clusters have made sure that local leaders have ensured the presence of basic needs; such as toilets and disability and elderly support.[80] According to a report released on 3 February, preliminary satellite data found that approximately 1400 km2 of land appeared to be flooded. About 80,000 people were exposed and/or living near flooded areas during 14–31 January. At least 10,00 buildings were located within or were close to flooded areas.[81] Citizens claimed the crisis in Cabo Delgado Province, which began in 2017 and killed more than 2,000 Mozambicans, has been exacerbated due to flooding brought by the cyclone. The safety of women and young girls was at further risk of being damaged.[82]

Crop damage and food shortages

This raised worry that families would not be able to have adequate food for much longer than originally anticipated.[9] The WFP has reported that it has over 640 metric tons of food available at its warehouse in Beira. The food was originally going to be used as part of its ongoing lean-season response, but it was instead used to feed those in need after the cyclone's passing.[63] A survivor in Guara Guara stated that there was no space where farming can be done. They also said that the Buzi district had good soil, and that people could set up farms in the district, and return to Guara Guara during the rainy season in March.[75] Assistance for food has been given to 13,045 as of 29 January, totaling up to 2,609 families in all accommodation centers in Beira City.[66]

Illness and risk of spreading

Due to conditions brought by the storm, malaria and acute diarrhoea treatment was needed.[76] Children were at risk of spreading disease as well. Cholera, a disease which has impacted Africa for many decades, was a risk for those sheltering. UNICEF's emergency teams worked with governments and partners to provide protection against infection, such as clean drinking water.[65] Aid workers warned that COVID-19, due to social distancing and cleanliness being ignored, could spread rapidly and further slow relief. Marcia Penicela, a project manager at ActionAid Mozambique, urged that people be moved out of danger of the virus and be provided vital necessities.[74] COVID-19 protection materials were paramount.[73] There was serious concern for those chronically ill, as they are unable to gather their much needed medications.[63] Essential medicine for up to 20,000 people was provided by UNICEF.[65]

Zimbabwe

In Zimbabwe, humanitarian supplies are also in need of distribution.[49] In the Bitika District of Masvingo province, preliminary assessments conducted by the District Development Coordinator highlighted water and sanitation as serious concerns for survivors. People had reportedly drank unsafe water after boreholes were swept away by floods. Nutrition and food was also a concern, as some mothers had begun to stop breastfeeding. In wards 1-3 of the district, blankets, mosquito nets, solar pumps, hygiene supplies, and jerry cans were requested.[46] More than 1,000 people were affected.[64] Following the spilling of the Tugwi Mukosi Dam, at least 172 people had to be relocated to safer areas.[64] Zimbabwe has had an increase in favorable water availability for crops and live stock, due to the widespread and heavy rainfall. However, it has also caused extensive soil leaching and waterlogging; this could impact any potential for crop yield, according to FEWSNET.[66]

Elsewhere

Authorities were sent to assess the extent damage in South Africa. By 29 January, heavy rains persisted over the country, due to the remnants of Eloise. Community development practitioners and other government officials identified 78 families affected by localized floods, the majority in Vhembe District.[66] Medical reps, bankers, university lecturers, and businessmen volunteered to help rescue operations in Mpumalanga and Limpopo. Police driving units and provincial disaster management units were supported. They helped retrieve the bodies of a five-year-old boy and a 40-year-old man who were swept away by the floodwaters.[83] Over 1,000 people were affected in Eswatini.[64]

See also

- Weather of 2021

- Tropical cyclones in 2021

- Tropical Storm Chalane – A storm that took a similar path earlier in the season

- Cyclone Guambe – Another cyclone that caused flooding in Mozambique less than a month later

- Cyclone Bonita – Took a similar track and devastated the same areas in 1996

- Cyclone Idai – Deadliest known South-West Indian Ocean tropical cyclone which catastrophically impacted the same region in Mozambique in 2019

- Cyclone Leon–Eline – A long-lasting cyclone that lasted the entirety of February in 2000, and also impacted Madagascar and central Mozambique

- Cyclone Bingiza – Impacted similar areas of Madagascar in 2011 as a Category 2-equivalent, killing 34

- Cyclone Hudah – Another long lasting cyclone in 2000 that impacted Madagascar and Mozambique

References

- ↑ "ELOISE : 2021-01-14 TO 2021-01-27". Météo-France La Réunion. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ↑ "Cyclone weakens in central Mozambique, but flooding a threat". AP News. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kirthana Pillay; Emma Rumney (25 January 2021). "Thirteen dead, thousands homeless in southern Africa after storm Eloise". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Eloise: Several dead as storm sweeps Africa's east coast". DW. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- 1 2 "At Least 3 Dead in Zim Floods as Storm Eloise Lashes Region". EWN. 24 January 2021. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coetzer, Marizka (27 January 2021). "Cyclone Eloise: Death toll in SA rises to four". The Citizen. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 11, As of 28 January 2021 - Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Limpopo floods: More than 10 drown, seven missing". Big News Network.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 9, As of 26 January 2021 - Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ↑ "Global Catastrophe Recap 2021" (PDF). AON Benfield. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ↑ "Global Catastrophe Recap – January 2021" (PDF). Aon Benfield. 9 February 2021. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Activity Bulletin for the South-West Indian Ocean" (PDF). Meteo France La Reunion. 15 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Activity Bulletin for the South-West Indian Ocean" (PDF). Meteo France La Reunion. 15 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ↑ "Moderate Tropical Storm 7 (Eloise)" (PDF). Meteo France La Reunion. 17 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ↑ "Moderate Tropical Storm 7 (Eloise)" (PDF). 18 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2021.

- ↑ "Severe Tropical Storm 7 (Eloise) Warning Number 14/07/20202021" (PDF). Meteo France La Reunion. 19 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2021.

- ↑ "A Moderate Tropical Storm 4 (Eloise) Warning Number 17/7/20202021" (PDF). Meteo France La Reunion. 19 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone 12S (Eloise) Warning NR 007". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Moderate Tropical Storm 7 (Eloise)" (PDF). Météo-France. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone 12S (Eloise) Warning NR 009". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone 12S (Eloise) Warning NR 010". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone 12S (Eloise) Warning NR 011". Archived from the original on 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "A Tropical Cyclone 7 (Eloise) Warning Number 30/7/20202021". Meteo France La Reunion. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone 12S (Eloise) Warning NR 012". Archived from the original on 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Moderate Tropical Storm 7 (Eloise) Warning Number 31/7/20202021". Meteo France La Reunion. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone 12S (Eloise) Warning NR 013". Archived from the original on 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Overland Depression 7 (Eloise)" (PDF). Meteo France La Reunion. 23 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ "Overland Depression 7 (Eloise) Warning Number 39/7/20202021" (PDF). Meteo France La Reunion. 25 January 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Southern Africa – Tropical Storm Eloise Flash Update No. 2, As of 19 January 2021 – Madagascar". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ "Preparedness and Response Flash Update | 14 January 2021 – Zimbabwe". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ "Overall Green alert Tropical Cyclone for ELOISE-21". Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ↑ "Overall Orange Tropical Cyclone alert for ELOISE-21 in Mozambique, Madagascar, Miscellaneous (French) Indian Ocean Islands from 17 Jan 2021 06:00 UTC to 19 Jan 2021 18:00 UTC". www.gdacs.org. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ "Global Disaster Alerting and Coordination System". www.gdacs.org. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ "18 January 2021 1200UTC forecast" (PDF). Météo-France. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ "19 January 2021 600UTC forecast" (PDF). metro france. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Madagascar: Moderate Tropical Storm Eloise makes landfall in the Sava region Jan. 19 /update 3". GardaWorld. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ "Southern Africa – Tropical Storm Eloise Flash Update No. 1" (PDF). Reliefweb. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Frightened Residents brace as Cyclone Eloise approaches Mozambique". africanews. 22 January 2021. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Mucari, Manuel; Rumney, Emma (22 January 2021). "Another cyclone, growing stronger, set to hit central Mozambique". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Southern Africa: Tropical Cyclone Eloise makes landfall in eastern Mozambique, Jan. 23 /update 9". GardaWorld. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ Pheto, Belina (22 January 2021). "Flooding and damaging winds expected as tropical cyclone Eloise hits". TimesLIVE. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Limpopo's disaster management teams on high alert as tropical storm "Eloise" moves inland". Polokwane Review. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ↑ "Limpopo vigilant as cyclone Eloise lashes Mozambique". SABC News. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Eloise: Gauteng is on alert". ENCA. 24 January 2021. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 7, As of 24 January 2021". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 10, As of 27 January 2021 - Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 5, As of 22 January 2021". ReliefWeb. 22 January 2021. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ Sithembile Hlatshwayo (21 January 2021). "Gearing Up For Cyclone". Times of Swaziland. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 8, As of 25 January 2021 - Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ "Cyclone Eloise on the loose, Malawi to have heavy rains — MET". Nyasa Times. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ "Weather experts closely monitoring Cyclone Eloise | Malawi 24 – Malawi news". Malawi 24. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ "Southern African countries on high alert as tropical storm Eloise intensifies". Eyewitness News. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- 1 2 "CMRSA_202101201800_ELOISE.pdf" (PDF). Météo-France. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ↑ "Mozambique, Madagascar, Zimbabwe – Tropical Cyclone ELOISE update (GDACS, INAM Mozambique, JTWC, Meteo Madagascar, UN OCHA) (ECHO Daily Flash of 22 January 2021)". ReliefWeb. 22 January 2021. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Cyclone Eloise brings floods to Mozambique's second city Beira". BBC. 24 January 2021. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "Cyclone hits Mozambique port city, brings property damage, flooding". Reuters. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ "Frightened Residents brace as Cyclone Eloise approaches Mozambique". AfricaNews. 22 January 2021. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 5, As of 22 January 2021". ReliefWeb. 22 January 2021. Archived from the original on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ↑ "Property damaged as Cyclone Eloise hits Mozambique's Beira". www.msn.com. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ mozambique. "Mozambique: Cyclone Eloise hits Beira – photos". Mozambique. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Cyclone Eloise makes landfall in disaster-impacted Sofala Province in Mozambique". UNFPA ESARO. 23 January 2021. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ↑ "Mozambique: Tropical Storm Eloise – Information Bulletin no. 1". ReliefWeb. 22 January 2021. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Mozambique: UN responds as thousands are caught in the wake of devastating Cyclone Eloise". UN News. 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 11, As of 28 January 2021 - Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Up to 90,000 children in central Mozambique urgently need humanitarian assistance in wake of Cyclone Eloise". www.unicef.org. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 12, As of 29 January 2021 - Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ↑ "Pics | Cyclone Eloise downgraded in severity, but floods hit KZN, Limpopo". news24. 24 January 2021. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ Mthethwa, Cebelihle (24 January 2021). "Kruger Park evacuates some camps, closes roads as Cyclone Eloise hits". News24. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "Southern Africa – Tropical Cyclone Eloise Flash Update No. 8, As of 25 January 2021 - Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ TimesLIVE (14 February 2021). "Destructive tropical storm Eloise officially declared a national disaster". Talk of the Town. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Eloise: Nearly 7,000 displaced in Mozambique". ENCA. 24 January 2021. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ IRFC, Africa (23 January 2021). "IRFC Africa on TwitterWe have released 359,689 Swiss francs from our Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF)—to help @CruzVermelhaMOZ to provide immediate relief and lifesaving assistance to 500 families that are affected by #CycloneEloise, for 3 months". Twitter. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Mozambique – Flash Report 15 | Evacuations to Accommodation Centres Update 2 (Tropical Cyclone Eloise) – IOM DTM/INGC Rapid Assessment (25 January 2021) – Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 Rumney, Emma (26 January 2021). "Aid workers warn on COVID-19 in camps for Mozambique cyclone victims". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- 1 2 AfricaNews (26 January 2021). "Cyclone Eloise Leaves Thousands Displaced in Central Mozambique". Africanews. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- 1 2 "Mozambique: Tropical Storm Eloise – Information Bulletin no. 2 – Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ "Food for the Hungry mobilizes immediate disaster relief response to Tropical Cyclone Eloise – Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ "Protection Cluster Mozambique Cyclone Eloise Flash Update #01 (31 Jan 2021) - Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ↑ "Climate-fuelled Cyclone Eloise compounded by Covid-19 leaves over 260K in urgent humanitarian need – Oxfam – Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ↑ "Mozambique |Eloise Response |Beira Accommodation Centers (1 February 2021) – Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ↑ "Satellite detected waters extents between 14 & 31 January 2021 in Sofala Province of Mozambique - Imagery analysis: 14-31 January 2021 | Published 3 February 2021 | Version 1.0" (PDF). ReliefWeb. 3 February 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ↑ "Turning the tide for women and girls caught in the Cabo Delgado crisis – Mozambique". ReliefWeb. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ↑ "Storm Eloise: Volunteers risk lives to save others, bring closure to bereaved families". TimesLIVE-ZA. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.