A cyclic cellular automaton is a kind of cellular automaton rule developed by David Griffeath and studied by several other cellular automaton researchers. In this system, each cell remains unchanged until some neighboring cell has a modular value exactly one unit larger than that of the cell itself, at which point it copies its neighbor's value. One-dimensional cyclic cellular automata can be interpreted as systems of interacting particles, while cyclic cellular automata in higher dimensions exhibit complex spiraling behavior.

Rules

As with any cellular automaton, the cyclic cellular automaton consists of a regular grid of cells in one or more dimensions. The cells can take on any of states, ranging from to . The first generation starts out with random states in each of the cells. In each subsequent generation, if a cell has a neighboring cell whose value is the successor of the cell's value, the cell is "consumed" and takes on the succeeding value. (Note that is the successor of ; see also modular arithmetic.) More general forms of this type of rule also include a threshold parameter, and only allow a cell to be consumed when the number of neighbors with the successor value exceeds this threshold.

One dimension

The one-dimensional cyclic cellular automaton has been extensively studied by Robert Fisch, a student of Griffeath.[1] Starting from a random configuration with n = 3 or n = 4, this type of rule can produce a pattern which, when presented as a time-space diagram, shows growing triangles of values competing for larger regions of the grid.

The boundaries between these regions can be viewed as moving particles which collide and interact with each other. In the three-state cyclic cellular automaton, the boundary between regions with values i and i + 1 (mod n) can be viewed as a particle that moves either leftwards or rightwards depending on the ordering of the regions; when a leftward-moving particle collides with a rightward-moving one, they annihilate each other, leaving two fewer particles in the system. This type of ballistic annihilation process occurs in several other cellular automata and related systems, including Rule 184, a cellular automaton used to model traffic flow.[2]

In the n = 4 automaton, the same two types of particles and the same annihilation reaction occur. Additionally, a boundary between regions with values i and i + 2 (mod n) can be viewed as a third type of particle, that remains stationary. A collision between a moving and a stationary particle results in a single moving particle moving in the opposite direction.

However, for n ≥ 5, random initial configurations tend to stabilize quickly rather than forming any non-trivial long-range dynamics. Griffeath has nicknamed this dichotomy between the long-range particle dynamics of the n = 3 and n = 4 automata on the one hand, and the static behavior of the n ≥ 5 automata on the other hand, "Bob's dilemma", after Bob Fisch.[3]

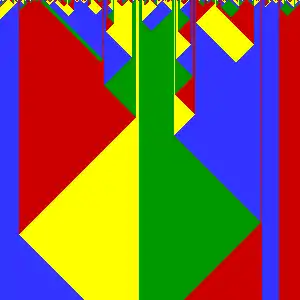

Two or more dimensions

In two dimensions, with no threshold and the von Neumann neighborhood or Moore neighborhood, this cellular automaton generates three general types of patterns sequentially, from random initial conditions on sufficiently large grids, regardless of n.[4] At first, the field is purely random. As cells consume their neighbors and get within range to be consumed by higher-ranking cells, the automaton goes to the consuming phase, where there are blocks of color advancing against remaining blocks of randomness. Important in further development are objects called demons, which are cycles of adjacent cells containing one cell of each state, in the cyclic order; these cycles continuously rotate and generate waves that spread out in a spiral pattern centered at the cells of the demon. The third stage, the demon stage, is dominated by these cycles. The demons with shorter cycles consume demons with longer cycles until, almost surely, every cell of the automaton eventually enters a repeating cycle of states, where the period of the repetition is either n or (for automata with n odd and the von Neumann neighborhood) n + 1. The same eventually-periodic behavior occurs also in higher dimensions. Small structures can also be constructed with any even period between n and 3n/2. Merging these structures, configurations can be built with a global super-polynomial period.[5]

For larger neighborhoods, similar spiraling behavior occurs for low thresholds, but for sufficiently high thresholds the automaton stabilizes in the block of color stage without forming spirals. At intermediate values of the threshold, a complex mix of color blocks and partial spirals, called turbulence, can form.[6] For appropriate choices of the number of states and the size of the neighborhood, the spiral patterns formed by this automaton can be made to resemble those of the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction in chemistry, or other systems of autowaves, although other cellular automata more accurately model the excitable medium that leads to this reaction.

Notes

- ↑ Fisch (1990a,1990b,1992).

- ↑ Belitsky and Ferrari (2005).

- ↑ Bob's Dilemma Archived 2007-04-29 at the Wayback Machine. Recipe 29 in David Griffeath's Primordial Soup Kitchen.

- ↑ Bunimovich and Troubetzkoy (1994); Dewdney (1989); Fisch, Gravner, and Griffeath (1992); Shalizi and Shalizi (2003); Steif (1995).

- ↑ Matamala and Moreno (2004)

- ↑ Turbulent Equilibrium in a Cyclic Cellular Automaton Archived 2007-04-28 at the Wayback Machine. Recipe 6 in David Griffeath's Primordial Soup Kitchen.

References

- Belitzky, Vladimir; Ferrari, Pablo A. (1995). "Ballistic annihilation and deterministic surface growth". Journal of Statistical Physics. 80 (3–4): 517–543. Bibcode:1995JSP....80..517B. doi:10.1007/BF02178546.

- Bunimovich L. A.; Troubetzkoy, S. E. (1994). "Rotators, periodicity, and absence of diffusion in cyclic cellular automata". Journal of Statistical Physics. 74 (1–2): 1–10. Bibcode:1994JSP....74....1B. doi:10.1007/BF02186804.

- Dewdney, A. K. (1989). "Computer Recreations: A cellular universe of debris, droplets, defects, and demons". Scientific American (August): 102–105.

- Fisch, R. (1990a). "The one-dimensional cyclic cellular automaton: A system with deterministic dynamics that emulates an interacting particle system with stochastic dynamics". Journal of Theoretical Probability. 3 (2): 311–338. doi:10.1007/BF01045164.

- Fisch, R. (1990b). "Cyclic cellular automata and related processes". Physica D. 45 (1–3): 19–25. Bibcode:1990PhyD...45...19F. doi:10.1016/0167-2789(90)90170-T. Reprinted in Gutowitz, Howard A., ed. (1991). Cellular Automata: Theory and Experiment. MIT Press/North-Holland. pp. 19–25. ISBN 0-262-57086-6.

- Fisch, R. (1992). "Clustering in the one-dimensional three-color cyclic cellular automaton". Annals of Probability. 20 (3): 1528–1548. doi:10.1214/aop/1176989705.

- Fisch, R.; Gravner, J.; Griffeath, D. (1991). "Threshold-Range Scaling of Excitable Cellular Automata". Statistics and Computing. 1: 23–39. arXiv:patt-sol/9304001. doi:10.1007/BF01890834.

- Matamala, Martín; Moreno, Eduardo (2004). "Dynamic of cyclic automata over Z^2". Theoretical Computer Science. 322 (2): 369–381. doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2004.03.018. hdl:10533/175114.

- Shalizi, Cosma Rohilla; Shalizi, Kristina Lisa (2003). "Quantifying self-organization in cyclic cellular automata". In Lutz Schimansky-Geier; Derek Abbott; Alexander Neiman; Christian Van den Broeck (eds.). Noise in Complex Systems and Stochastic Dynamics. Bellingham, Washington: SPIE. pp. 108–117. arXiv:nlin/0507067. Bibcode:2005nlin......7067R.

- Steif, Jeffrey E. (1995). "Two applications of percolation to cellular automata". Journal of Statistical Physics. 78 (5–6): 1325–1335. Bibcode:1995JSP....78.1325S. doi:10.1007/BF02180134.