The cuisine of the Vale of Glamorgan (Welsh: Bro Morgannwg), Wales, is noted for its high-quality food produced from the fertile farmland, river valleys and coast that make up the region. The area has a long history of agriculture that has developed from the Roman era.

The Vale is not a valley in the geographical sense, but a plateau. It lies at between 50 and 2,000 feet above sea level and rises to 4,000 feet at Mynydd Margam and Garth Hill. This makes it a homogeneous region with distinct characteristics which set it apart from the adjacent regions.[1]

Most of the Vale is made up of prime agricultural land due to its fertile, rich soil which is light and easily worked. As a result, the area has developed a mixed farming economy. It produces wheat and other cereals, grows hay for pasture and is good for animal husbandry.[2]

The Vale has many small villages and market towns which are relatively evenly distributed and are often hidden in secluded river valleys and connected by country lanes. The rivers are relatively short in length and have their source in the adjacent uplands, known as the Blaenau Morgannwg, which consists of a line of hills to the north of the Vale and which form the foothills to the higher mountains of Brecknockshire.[3] The southern boundary of the Vale is made up of the coastline of the Bristol Channel, which has a tidal range of up to 40 ft. There are few good harbours, other than Aberthaw which was a popular location for smuggling in the eighteenth century.[4]

Arterial roads run through the Vale and connect the more populated nearby areas of the South Wales Valleys to the north, Cardiff to the east, and Neath and Swansea to the west. Since the Industrial Revolution these more densely populated areas have provided markets for the sale of the Vale's beef, lamb and dairy products.[5]

Meat

Glamorgan cattle is a Welsh traditional cattle breed with a chestnut coloured coat and a broad white stripe which runs along the backbone to the tail and under the abdomen. Morgan Evans comments that the breed was once highly prized and belongs to a class of cattle called middle-horns. In character and antiquity of descent they rank with Hereford cattle, South Devon cattle, North Devon cattle, and Welsh Black cattle.[6]

The breed originated from an ancient variety which, according to Freeman, has an identical counterpart in the Pinzgauer cattle of Austria. It is believed that the Celts brought them to Wales during their migration westward. The Norman lord Robert Fitzhamon, who took control of Glamorgan, cross bred these with cattle from Normandy to give the present breed of Glamorgan cattle. According to William Youatt the influence of Devon cattle can also be seen in the bloodline because they were introduced into the Vale by Richard de Grenville, one of the Twelve Knights of Glamorgan.[7]

Glamorgan cattle continued as a distinct breed because farmers were careful to maintain the purity of the bloodstock. They would be fattened in England at six or seven years old and then sent to London and other English cities to supply beef. Evans comments as follows:

“The Glamorgan cattle produced a rare quality of meat, highly prized in the metropolitan and provincial markets. They were profitable to the butchers, being well lined inside with tallow, and their meat, from its first-rate quality, always commanded the highest price.”

Before mechanisation a strong ox was required to plough the land and if the breed could also provide milk then this was considered the best combination. Glamorgan cattle were recognised for these qualities and also yielded up to 800 to 1,200 pounds of beef. Consequently, the breed was popular in the grazing counties of Northamptonshire, Warwickshire, Wiltshire and Leicestershire. George III also had a herd at his farm at Windsor Great Park. However, during the nineteenth century the move toward stall and grain feeding made it more profitable to feed shorthorn cattle which were more productive and by 1872 the American Agriculturalist commented that:[8]

“As a race which has passed its point of usefulness it has almost disappeared, and will soon be forgotten, and exist only in the records of the past”.

Morgan Evans explains that the breed declined because of the high price of corn during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. This led to the replacement of old grazing pastures by larger fields devoted to growing corn. After the price of corn stabilised Glamorgan farmers reverted to shorthorn varieties which had advanced through selective breeding and were good for beef and milk.[9]

It was believed that Glamorgan cattle had become extinct in the 1920’s, but a herd was discovered in Sussex in 1979 and the entire herd was purchased by West Glamorgan County Council. These cattle are now kept at Margam Country Park and this saved the breed from extinction.[10][11]

During the twentieth century Hereford cattle became the main beef breed, while Holstein Friesian cattle were popular as a dual beef and milk producer. In more exposed areas Galloway cattle and Welsh Black cattle were preferred.[12]

Colin Pressdee comments that the Vale produces exceptional quality beef and recommends that when buying it the flesh should be dark “with speckles of fat in the lean” which is called marbling. This keeps the meat moist during cooking. He comments that a roast of rib steak is the best way to eat beef, as smaller pieces can become overcooked.[13] Traditionally, for smaller pieces of beef, a stew would be made and this would produce two meals, the first of meat and vegetables and the second a broth.[14]

Many mixed farms also raise sheep. The Glamorgan Welsh is a local breed and is the largest of the Welsh Mountain Sheep breeds. According to the South Wales Mountain Sheep Society it shares the same primitive ancestry but has been “bred to a definite local type”. It is also known as the Nelson or South Wales Mountain Sheep and is found in the hill districts of Glamorgan, Gwent and south of the Brecon Beacons. Other sheep breeds in the Vale include the Hill Radnor, Suffolk sheep and Clun Forest sheep, which are often cross bred.[15][16]

Some farms in the Vale have been in the same family ownership for many generations and many use a traditional rotational grazing system producing lamb, beef, and pork.[17][18] Farms nearer the coast specialise in rearing and fattening cattle with a focus on fat lamb and beef.

Farmers in Glamorgan used to trade their livestock at the mart at Cowbridge, which was granted a charter in 1254. The mart allowed stock to be sold directly to buyers and this led to Cowbridge developing as a centre for food shops, delicatessens and restaurants. However, the Cowbridge mart closed on 1 September 2020, leaving the closest marts at Raglan, Carmarthen and Brecon.[19]

In 2014, a group of Glamorgan farmers established “Cows on Tour” to educate children about the story of food and farming. They visited schools and gave workshops on how to milk a cow and how to make butter with the aim to teach pupils where food comes from and how it is used in common brands of food.[20]

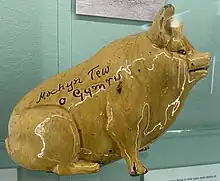

The pig is often a subsidiary part of the mixed farm.[21] In 1918, Glamorgan farmers established The Old Glamorgan Pig Society. This was in response to the restriction on imports of pork and bacon due to World War I. This was the first pig breeding society in Wales and its first herd book was published in 1919. In 1920 the society amalgamated to form the Welsh Pig Society because similar breed types were also being raised in Ceredigion, Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire. This created the breed known as the Welsh pig which has had its own herd book with the National Pig Association since 1953.[22]

Black Pudding (Pending Gwaed) is a traditional recipe made with the pig’s blood on the day the pig is killed. Tibbot refers to a recipe from Nantgarw and notes that the blood is poured into a large bowl and stirred while warm to avoid clotting. It is then diluted with water, salt is added and it is left to stand overnight. The pig’s small intestine is thoroughly washed and left in salt water overnight. Chopped onions are coated with fat from the intestine. Oatmeal and herbs are added and then mixed in the blood. The mixture is then added to the intestine which is tied with string at both ends, leaving room for expansion when boiled. The pudding is then boiled in water and hung to dry. Slices of the pudding are then fried with bacon.[23]

Fish

The Glamorgan coastline extends to about 90 miles in length, with the eastern shore formed by low-lying flats made up of alluvial deposits which continue until the estuary of the River Taff. Between Penarth and Lavernock the coast forms cliffs and then continues as a low rocky shore until it reaches Barry. From there, the coast leads to extensive sand dunes and then to Swansea Bay and the Gower Peninsula.[24]

Fish caught along the coast of Glamorgan include cod, sole, haddock, bream, hake, skate, common ling, conger eel and whiting in their respective seasons. However, halibut is rare and haddock and plaice not very abundant.[25]

The rivers of the Vale are relatively small and include the Ewenny, Ogmore, Ely and Thaw. They hold game fish such as brown trout, grayling and sea trout. Pressdee notes that salmon are known to run up the Ely and Ogmore. However, there is little commercial fishing, because the geography of the Vale means that the rivers are short in length. This means that fish are caught for domestic consumption and are usually baked or grilled.[26]

Welsh dishes for trout tend to be simple. Baked Trout with Oatmeal is a dish where the trout is cleaned, gutted and rolled in oatmeal, bacon fat is added and the fish is then baked.[27] Trout with Bacon involves wrapping the trout in bacon which lubricates the fish and to which lemon and parsley may be added.[28][29]

Milk products

The most important agricultural activity of the Vale is dairy farming. During the nineteenth century industrialisation led to an increased demand for milk and dairy produce from towns such as Barry and Cardiff. This led to an increase in the amount of pasture and a decrease in the amount of arable land in Glamorgan. This led to an extensive industry in the production of butter and cheese.[30] Distribution was helped by the growth of rail transport and this, combined with rising wages, meant that milk became more profitable than butter or cheese production.[31]

Until their disappearance, Glamorgan Cattle supplied milk which was used in cheese making. Glamorgan cheese had a distinctive flavour from this milk. Freeman writes that it was a fine, hard white cheese which was similar to Caerphilly cheese.[32]

The American Agriculturalist[33] commented on this as follows:

However, it is quite probable that to the influence of this race the present excellence of the cheese dairies of Gloucester, an adjoining county in England, is due, for the Gloucester cows show a striking relationship to the ancient Glamorgans, but they too are also passing away,..

Freeman writes as follows:[34]

“In the Vale of Glamorgan fat ewe’s milk was added to skimmed cow’s milk for cheese. In 1662 Welsh cheese was described as ‘very tender and palatable’ and the dairy farmers of the Vale of Glamorgan exported cheese to Bristol and other Somerset ports.”

Vegetarian

One of the best-known recipes from Glamorgan is the Glamorgan sausage. The sausage got its name from Glamorgan cheese which was a key ingredient. However, with the disappearance of Glamorgan cheese contemporary recipes use Caerphilly cheese. The sausage mix is kept intact by the casing. Freeman preferred to use half white and half brown bread crumbs for the casing and comments that the onions must be finely chopped to keep the sausage mixture together. The egg yolk is divided from the egg white and the dry ingredients of chopped onion, herbs, mustard, and grated cheese are bound together with the egg yolk. The small sausages are then rolled in flour, dipped in the egg white, rolled in bread crumbs and fried. [35]

Glamorgan sausages are mentioned by George Borrow in his book Wild Wales:[36]

“The breakfast was delicious, consisting of excellent tea, buttered toast and Glamorgan sausages, which I really think are not a whit inferior to those of Epping”

The recipe was popular during World War II because it does not require meat, which was subject to rationing during this period. It has since become a popular component of vegetarian cuisine.[37]

Vegetables and fruit

The Vale has some of the most fertile agricultural land of Glamorgan with the soils mainly clay loam derived from the Lias Group of limestone and shales which form a brown earth which is high in calcium and which has good drainage. This means the soil makes very productive arable land although mixed farming predominates.[38]

One of the Vale’s most famous characters was Iolo Morgannwg who wrote a poem called The Happy Farmer which celebrates the traditional mixed farming of the Vale during his time:[39]

"I live on my farm in a beautiful vale,

Ye lovers of Nature attend to my tale;

No pride or ambition find room in my breast,

Those venomous foes of contentment and rest;

From sound healthy sleep I rise up every morn,

To toll in my fields with my cattle and corn,

…..

The flocks in pastures are fair to behold,

Fine cows with large udders replenish my fold;

My fields yield abundance, in tillage complete,

Good barley, rich clover, and excellent wheat;

Slade Farm, near St Brides Major, is an example of a Glamorgan farm that has a Community supported agriculture scheme (CSA). Under this scheme the farm grows vegetables throughout the year for local families that have enrolled on to the CSA scheme. The aim of the scheme is to offer sustainable food to families who live around the farm with a view to developing supply-chain sustainability. The farm is also an example of an organic farm that does not use pesticides or herbicides and actively develops the farmland for native species of farmland birds, wildflowers and animals. The farm also allows visits at lambing time, farm walks, and open days. It is a member of the Nature Friendly Farming Network.[40][41]

Soft fruit is grown at a number of Vale farms and a number of these have pick your own facilities. Iolo Morgannwg refers to soft fruit in his poem:

“My flourishing orchard abundantly bears

Fine plums, golden-pippins, and bergamot pears;”

Freeman comments that the Vale is one of the few areas in Wales where crab apples grow. Crab Apple Jelly is used in a Glamorgan recipe known as Crab Cake (Teisen Afalau Surion Bach). This is a type of bakestone cake made from a dough made from flour, butter, sugar, salt and nutmeg. This is then filled with the crab apple jelly.[42]

Bread and cakes

Until the end of the eighteenth-century bread was baked from barley flour. This gave the old Glamorgan ploughman’s saying:

“Better barley bread and peace than white bread and discord”

Barley bread was relatively heavy because it did not contain much gluten. It was used to make thin, flat loaves on the bakestone. These would sometimes be used as ‘plates’ for food and be eaten as well as the food on top.[43]

According to Freeman, making the old breads of Wales from whole wheat flour, barley meal, oatmeal and rye flour:

“required great skill and ingenuity to produce acceptable bread in primitive conditions. Sometimes bread was baked in the wall oven, or in a bread oven housed in a separate little building across the yard from the house.”

In Wales, corn was ground at small mills on the banks of fast flowing rivers and streams, although the Vale and Anglesey were also noted for their windmills.[44]

According to a letter in the Gentleman's Magazine of 1785, Glamorgan was known for the quality of its wheat [45]

'The wheat is equal to the best in the kingdom'.

The growth of coal mining and metallurgical activities in the county led to an increase in the local population which stimulated arable production. The erection of blast furnaces in places such as Merthyr Tydfil and Neath meant that the county did not grow sufficient corn for its own consumption. The result was a large increase in the quantity of land which was put to arable use. Before this, Glamorgan used annually to export a large quantity of corn to Bristol.[46]

Walter Davies, in his survey of the general economy of Glamorgan commented on the Vale as follows:[47]

In the lowlands, on moist loams ... grazing is considerable and generally recommended, as most profitable. But the steady increase of population, as steadily increasing consumption of food, and that in Wales consisting chiefly of bread, decides the controversy between speculative theorists, turns the balance of profit, by an advance in the price of grain, to the scales of tillage.

There are several cake recipes from this area, Round Cakes (Teisennau Crwn) were baked in a shallow tin under a hot grill or in a Dutch oven. Tibbot refers to a recipe from North Cornelly made by rubbing butter and lard into flour to which is added currants, sugar, nutmeg and salt. A mixture of beaten egg and some milk is then added and is kneaded into a dough which is rolled out and cut into small rounds.[48]

On Welsh cakes Tibbott comments:[49]

“It is certain that the cakes, generally known today as ‘Welsh Cakes’, have been tea-time favourites in Glamorgan since the latter decades of the last century. At one period they would be eaten regularly in farmhouses and cottages alike, and the miner would also expect to find them in his food-box. Two different methods of baking these cakes were practised in Glamorgan. Baking them on a bakestone over an open fire may be regarded as the most general practice throughout the county. The Welsh names given to the cakes were usually based on the Welsh name for the bakestone, and these include pice ar y mân, tishan ar y mân and tishen lechwan. They varied in size from small, round cakes to a single cake as big as the bakestone. The method favoured in the Vale of Glamorgan, on the other hand, was to bake them in a Dutch oven in front of an open fire. The cakes were cut into small rounds, placed in two or three rows on the bottom of the oven and baked in front of a clean, red glow. These were known as pica/pice bach, tishan gron, and tishen rown. Slashers and tishan whîls were colloquial names given to them in two small villages”

Tibbott gives a recipe for Welsh Cakes from North Cornelly where the flour, salt, and spice are sifted together, the butter rubbed in, sugar is added and a beaten egg is mixed in and the dough is kneaded until it is soft and dry. Currants are then worked into half of the dough and both halves are rolled out and cut into small rounds and baked on a bakestone. The plain cakes are split open and spread with jam. Alternatively the dough is rolled out into one large round to which is baked on both sides, split open and spread with stewed apple and brown sugar and covered with the other half and cut into squares.[50]

Tibbott mentions recipes for Bakestone Cake (Teisen Lechwan), Bakestone Pie (Teisen ar y Maen) and Bakestone Turnover (Teisen ar y Maen). The dough for Bakestone Turnover and Bakestone Cake is prepared in the same way, although the former uses less fat and sugar. The butter and lard are added to flour, sugar and currants and then beaten eggs and some milk are added to make a soft dough. In the case of a Bakestone Cake, this is rolled out on to a floured board and cut into small rounds which are baked on a bakestone. In the case of a Bakestone Turnover the dough is rolled out to the size of a dinner plate half of which is covered with fruit, such as sliced apple, blackberries or gooseberries. The other half is folded over the fruit and the edges are pressed together and sealed. The pie is also baked on a hot bakestone and the top layer of the pie is split open to add sugar and then re-covered. Tibbott mentions that the Bakestone Turnover was prepared on farms during harvest time.[51]

In the case of Bakestone Pie the ingredients included lard and flour, which are mixed with salt and water to make a short pastry. This is divided into two parts and rolled into the size of a dinner plate. The fruit is placed over one part and then covered with the other piece of pastry and then sealed. The pie is then baked on the bakestone. The top is removed to add sugar and butter and re-covered with the pastry. Tibbott has recorded a Bakestone Pie recipe from Kenfig Hill and mentions that Teisen ar y Maen is similar to Teisen Blât (Plate Cake) which is baked on a plate in the oven.[52]

Pancakes (Ffroes) are made with plain flour, butter, lard, eggs and milk and currants can also be added. The butter and lard are melted and poured into the flour which is beaten into a batter. Half a cup full of batter is poured on to a hot bakestone and then baked on both sides. When the pancake is ready it is placed on a plate and spread with butter and some sugar. Tibbott gives a recipe for Ffroes from Dowlais and mentions that it was a general tradition to prepare pancakes for afternoon tea when celebrating the birthday of a family member. In the case of Ffroes Eira (Snow Pancakes) clean snow is used instead of water and gives the Ffroes a lighter consistency.[53]

Tinker’s Cake (Teisen Dinca) is made with flour, butter, brown sugar and shredded apple. The ingredients are mixed with some milk and kneaded into a stiff dough and then rolled out on a floured board to make rounds of up to an inch thick. These are baked on the bakestone and cut into squares. Tibbott mentions a recipe from Gwaelod-y-Garth and another recipe from Pentyrch where a beaten egg is added to make a softer dough similar to Teisen Lap. In this case the mixture would be baked in a Dutch oven in front of the fire.[54]

Loaf Cake was a cake made at Christmas, the dough would be prepared in large quantities and carried to the local bakery where the baker would be responsible for baking the cakes for a penny or two per loaf. Neighbours would be invited to taste each other’s cake. In the district of Margam, the tradition was that if a young maid was given the opportunity to taste thirteen different cakes in one season she would get married before the following Christmas.[55] Boiled Milk Cake (Cacen Llaeth Berw) is a cake made with flour, butter, brown sugar, currants and raisins and mixed with half a pint of boiled milk. The mixture is added to a greased cake tin and baked in a hot oven. Tibbott has collected a recipe from Whitchurch for this cake.[56]

Lardy Cake (Cacen Lard) is a popular cake which was usually made on bread-baking day in parts of Glamorgan. It is made from dough, with lard, currants, candied fruit peel and sugar worked into the mix.[57] Freeman comments that rhubarb and gooseberries are commonplace in Wales and so: "there are a large clutch of recipes for them". Freeman mentions two recipes, as follows:

Rhubarb Shortcake is a Glamorganshire recipe where sticks of rhubarb are cooked in a casserole in the oven with some water and sugar until tender. A shortcake mixture is rolled and cut into two pieces. An oblong shape is made with one half and placed on a greased baking tin. The rhubarb is spread on top and the other half of the shortcake mix is put on top and then the dish is baked.

Gooseberry Pudding is another Glamorgan recipe where the fruit is stewed until it is turned to a pulp and then sugar, butter, and bread crumbs are added. Once the mix is cool two eggs are added and stirred into the mixture which is then baked for half an hour in a buttered dish.[58]

Drink

There are several vineyards in Glamorgan. St Hilary Vineyard was planted in 2020 near Cowbridge and grows Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, and Chardonnay, with the aim of producing a high quality sparkling wine. Croffta Vineyard is located at Groes-faen and produces a sparkling wine using Seyval blanc grapes and the Traditional method (La Mèthod Traditionnelle) which produces fine bubbles associated with a premium sparkling wine. Glyndwr Vineyard is located at Llanblethian and was established in 1979. Llanerch Vineyard was established in 1986 when a Kerner variety was planted and vines of French and German varieties such as Triomphe d’Alsace, Bacchus, Reichensteiner and Huxelrebe.[59]

A few breweries operate in the Vale (see Beer in Wales). Vale of Glamorgan Brewery is based in Barry and was established in 2005. Glamorgan Brewery which is a family owned brewery based in Llantrisant and was founded in 1994. It produces different types of beer and cider. Tomos & Lilford is a brewery based in Cowbridge and produces beers named after local places: Nash Point (a gluten free bitter), Southerndown Gold (an India pale ale) and Vale Pale (a lactose free pale ale).

Spirit producers in the Vale include Barry Island Spirits Co which produces small batches of gin, rum and vodka and is based in Barry Island. Penarth Gin is a Welsh dry gin made in Penarth by Gin64. Hensol Castle has its own distillery that produces Hensol Castle Gin and provides tours and tastings.

References

- ↑ Evans, C.J.O: Glamorgan, It’s History and Topography, pages 7, 8. Cardiff: William Lewis (Printers) Ltd, 1938. ASIN B0010OH590

- ↑ Evans, Glamorgan, It’s History and Topography, page 8, 26, 131

- ↑ Evans, Glamorgan, It’s History and Topography, page 3, 6

- ↑ Evans, Glamorgan, It’s History and Topography, page 6

- ↑ Howell, David, W.: Land and People in Nineteenth Century Wales, page 12. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016. ISBN 978-1-138-63979-9

- ↑ Coleman, C., J., D., B.: The Cattle of Great Britain, being a Series of Articles on the Various Breeds of Cattle of the United Kingdom, their History and Management &c, page 118-119. London: The Field Office, 1875.ISBN 0781805279

- ↑ Bobby Freeman: Traditional Food from Wales, page 152. New York: Hippocrene Books Inc., 1997.ISBN 0781805279

- ↑ The American Agriculturalist. New York: 1876

- ↑ Coleman, The Cattle of Great Britain, page 118-119

- ↑ "Margam Country Park".

- ↑ "Pure Grass Beef, Lost Breeds".

- ↑ Rees, J., F. (editor): The Cardiff Region, A Survey, page 141. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1960.ASIN B0010NXC24

- ↑ Pressdee, Colin: Colin Pressdee's Welsh Coastal Cookery, page 100. London: BBC Books, 1995. ISBN 0 563 37136 6

- ↑ Anon:Favourite Welsh Recipes, Traditional Welsh Fare, Bwyd Traddodiadol o Gymru, page 32. Sevenoaks: J Salmon Limited, 2018. ISBN 978-1906473945

- ↑ Rees, The Cardiff Region, page 142

- ↑ "South Wales Mountain Sheep".

- ↑ "Big Barn, Glamorgan Lamb".

- ↑ "Big Barn, C G Morgan & Son".

- ↑ "Wales 247, Glamorgan Farmers left in dark over Local Mart".

- ↑ "Farming UK, Cows on Tour visit London school to tell farming story".

- ↑ Rees, The Cardiff Region, page 242

- ↑ "Happerly organisations".

- ↑ Tibbott, S. M.: Welsh Fare: A Selection of Traditional Recipes, page 17. Cardiff: National Museums and Galleries of Wales; New Edition, 1976. ISBN 978-0854850402

- ↑ Evans, Glamorgan, It’s History and Topography, page 10

- ↑ Evans, Glamorgan, It’s History and Topography, page 140

- ↑ Pressdee, Welsh Coastal Cookery, page 10

- ↑ Freeman, B: Welsh Country Cookery, Traditional Recipes from the Country Kitchens of Wales, page 53. Talybont: Y Lolfa, 2003. ISBN 0 86243 133 6

- ↑ Freeman, Welsh Country Cookery, page 23

- ↑ "Fishing Wales, locations".

- ↑ Evans, Glamorgan, It’s History and Topography , page 133,134

- ↑ Howell, Land and People in Nineteenth Century Wales, page 126-127

- ↑ Freeman, Traditional Food from Wales, page 152

- ↑ American Agriculturalist, 1876

- ↑ Freeman, Traditional Food from Wales, page 32

- ↑ Freeman, Traditional Food from Wales, page 152

- ↑ Freeman, Traditional Food from Wales, page 151

- ↑ "The Recipe Hunters, Glamorgan Sausages".

- ↑ Rees, The Cardiff Region, page 137

- ↑ "Cowbridge News, The Happy Farmer, by Iolo Morgannwg".

- ↑ "Slade Farm Organics".

- ↑ "Nffn farmers".

- ↑ Freeman, Welsh Country Cookery, page 26

- ↑ Freeman, B.: A Book of Welsh Bread, page 7. Talybont: Y Lolfa, 2020.ISBN 978-1784618919

- ↑ Freeman: A Book of Welsh Bread, page 7

- ↑ Anon: 'A Letter to Mr. Urban'. Gentleman's Magazine, Vol. 55, pt. 2, 1785, p. 604

- ↑ "Glamorgan Archives, Quoted in Minchinton, op cit.]]".

- ↑ Davies, W.: A General View of the Agriculture and Domestic Economy of South Wales, volume 1, page 161. London 1814 (republished by Hardpress Publishing 2020). ISBN 9780371281963

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 24

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 24

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 25

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 26

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 26

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 28

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 33

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 36

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 39

- ↑ Tibbott, Welsh Fare, page 39

- ↑ Freeman, Traditional Food from Wales, page 178

- ↑ "Croffta Vineyard".