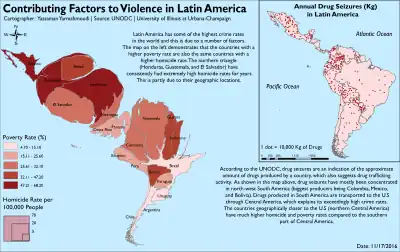

Crime and violence affect the lives of millions of people in Latin America. Some consider social inequality to be a major contributing factor to levels of violence in Latin America,[1] where the state fails to prevent crime and organized crime takes over State control in areas where the State is unable to assist the society such as in impoverished communities. In the years following the transitions from authoritarianism to democracy, crime and violence have become major problems in Latin America. The region experienced more than 2.5 million murders between 2000 and 2017.[2] Several studies indicated the existence of an epidemic in the region; the Pan American Health Organization called violence in Latin America "the social pandemic of the 20th century."[3] Apart from the direct human cost, the rise in crime and violence has imposed significant social costs and has made much more difficult the processes of economic and social development, democratic consolidation and regional integration in the Americas.[4]

Consequences for the region

High rates of crime and violence in Latin America are undermining growth, threatening human welfare, and impeding social development, according to World Bank and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).[5] According to the Financial Times, "The region registers close to 40 per cent of the world’s murders despite being home to only 9 per cent of the global population. According to LAPOP, one in four Latin Americans was assaulted and robbed" in 2018.[6] Latin America is caught in a vicious cycle, where economic growth is thwarted by high crime rates, leading many to believe that because of the insufficient economic opportunity in the region, Latin America cannot navigate their way out of the problem. However, there are many contributing factors to the problem of crime and violence in Latin America, such as the Drug Trade, Cartels and corruption in the political and judicial systems.[7] Crime and violence thrives as the rule of law is weak, economic opportunity is scarce, and education is poor. Therefore, effectively addressing crime requires a holistic, multi-sectoral approach that addresses its root social, political, and economic causes.

Recent statistics indicate that crime is becoming the biggest problem in Latin America.[8] Amnesty International has declared Latin America as the most dangerous region in the world for journalists to work.[9]

In Mexico, armed gangs of rival drug smugglers have been fighting it out with one another, thus creating new hazards in rural areas. Crime is extremely high in all of the major cities in Brazil. Wealthy citizens have had to provide for their own security. In large parts of Rio de Janeiro, armed criminal gangs are said to be in control. Crime statistics were high in El Salvador, Guatemala and Venezuela during 1996. The police have not been able to handle the work load and the military have been called in to assist in these countries.[10] There was a very distinct crime wave happening in Latin America.[11] The city that currently topped the list of the world's most violent cities is San Pedro Sula in Honduras, leading various media sources to label it the "murder capital of the world."[12][13][14][15] Colombia registered a homicide rate of 24.4 per 100,000 in 2016, the lowest since 1974. The 40-year low in murders came the same year that the Colombian government signed a peace agreement with the FARC.[16]

Crime is slowing economic growth and undermining democratic consolidation in Latin America.[17][18] Today, Latin America has the dubious distinction of being most violent region in the world, with combined crime rates more than triple the world average and are comparable to rates in nations experiencing war. This is taking a tremendous toll on development in the region by both affecting economic growth and public faith in democracy.

The Inter-American Development Bank estimates that Latin America's per capita Gross Domestic Product would be twenty-five percent higher if the region's crime rates were equal to the world average. Similarly, the World Bank has identified a strong correlation between crime and income inequality.[19] Business associations in the region rank crime as the number one issue negatively affecting trade and investment. Crime-related violence also represents the most important threat to public health, striking more victims than HIV/AIDS or other infectious diseases.[20]

_-_Bolivia-15.jpg.webp)

Public faith in democracy itself is under threat as governments are perceived as unable to deliver basic services such as public security. A United Nations report revealed that only 43 percent of Latin Americans are fully supportive of democracy.[21] Crime has rapidly risen to the top of the list of citizen concerns in Latin America. As the Economist magazine described it, "in several Latin American countries, 2004 will be remembered as the year in which the people rose up in revolt against crime."[22][23]

Massive street marches such as those that took place in Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil, and other expressions of protest against violence, have made it increasingly difficult for politicians to avoid dealing with the issue and, in many countries, have made tackling crime a central theme in political party platforms across the region. Several leaders in the region, including El Salvador's Tony Saca, Ricardo Maduro in Honduras, Guatemala's Óscar Berger, and Álvaro Uribe in Colombia, have all campaigned on a strong anti-crime message. The Presidents of Honduras and El Salvador have called gangs (maras) as big a threat to national security in their countries as terrorism is to the United States.[22][24]

"World Bank researchers have demonstrated the existence of a 'criminal inertia,' in which high rates of criminality endure long after the latent socioeconomic causes have disappeared or been addressed through policy interventions."[25][26]

Another reason critics believe fuels crime in Latin America is due to the poor public primary education system they say it "has given rise to youths without jobs or expectations of employment-thereby fueling the mounting problem of gang violence in Central America, Mexico, Jamaica, Trinidad, Colombia and Brazil."[27]

Contributing factors

A series of factors have contributed to the increase in violent crime in Latin America since the transitions from authoritarianism to democracy. Some intrinsic factors and characteristics of each country aggravated the problem in some countries. However, some factors might have increased the risk of crime and violence in many or most countries in the region in the period between the 1980s and 1990s:[4]

- High levels of social inequality

- Civil wars and armed conflicts

- Low rates of economic growth

- High unemployment rates

- Rapid growth of large cities and metropolitan areas

- Absence/weakness of basic urban infrastructure, basic social services and community organizations in the poorest neighborhoods, in the periphery of large cities and metropolitan areas

- Growing availability of arms and drugs

- Growing presence and strengthening of organized crime

- Culture of violence, reinforced by organized crime as well as the media, the police and the private security services

- Low level of effectiveness of the police and other institutions in the criminal justice system

- Poor public education system.

- Corruption and bribery reaching high levels in Law Enforcement, political, religious and business institutions.

Nations with high crime rates

Brazil

Brazil is one of the countries that has the largest inequality in terms of the gap between the very wealthy and the extremely destitute. A huge portion of the population lives in poverty. According to the World Bank, "one-fifth of Brazil's 173 million people account for only a 2.2 percent share of the national income. Brazil is second only to South Africa in a world ranking of income inequality.[29]

There were a total of 63,880 murders in Brazil in 2018.[30] The incidence of violent crime, including muggings, armed robbery, murder and sexual assault is high, particularly in Rio de Janeiro, Recife and other large cities. Carjacking is also common, particularly in major cities. The statistics posted by the Brazilian Public Security Forum indicated that over 47,000 violent crimes were committed in 2019.[31] Crime levels in the Brazilian favelas are considerably higher than other areas due to gangs controlling the areas.[32] Victims of these gangs, both inside and outside the "no-go" areas, have been seriously injured or killed when attempting to resist their perpetrators. During peak tourist seasons, large, organized criminal gangs have reportedly robbed and assaulted beach goers.[33] The country is well known for having almost 60,000 documented murders every year for the past decade, mostly drug and robbery related.

'Express kidnappings', where individuals are abducted and forced to withdraw funds from automated teller machines to secure their release, are common in major cities including Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and Recife. People have been robbed and assaulted when using unregistered taxis. Petty crime such as pickpocketing and bag snatching are common. Thieves operate in outdoor markets, in hotels and on public transport.

Colombia

Elements of all the armed groups have been involved in drug-trafficking. In a country where the presence of the state has always been weak, the result has been a grinding war on multiple fronts, with the civilian population caught in the crossfire and often deliberately targeted for "collaborating". Human rights advocates blame paramilitaries for massacres, "disappearances", and cases of torture and forced displacement. Rebel groups such as the FARC and the ELN are behind assassinations, kidnapping and extortion.[34] The level of drug related violence was halved in the last 10 years, when the country moved from being the most violent country in the world to have a homicide rate that is inferior to the one registered in countries like Honduras, Jamaica, El Salvador, Venezuela, Guatemala, Trinidad and Tobago and South Africa.[35]

The administration of President Uribe has sought to professionalize the armed forces and to engage them more fully in the counterinsurgency war; as a result, the armed groups have suffered a series of setbacks. Police in Colombia say the number of people kidnapped has fallen 92% since 2000. Common criminals are now the perpetrators of the overwhelming majority of kidnappings. By the year 2016, the number of kidnappings in Colombia had declined to 205 and it continues to decline.[36][37]

Colombia registered a homicide rate of 24.4 per 100,000 in 2016, the lowest since 1974. The 40-year low in murders came the same year that the Colombian government signed a peace agreement with the FARC.[16]

El Salvador

Violent crime is rampant in El Salvador, in 2012 the homicide rate peaked at 105 homicides per 100,000 residents. In 2016, the rate decreased by 20%, but El Salvador continues to be one of the world's most dangerous countries.[38] As of March 2012, El Salvador has seen a 40% drop in crime due to what the Salvadoran government called a gang truce. In early 2012, there were on average of 16 killings per day but in late March that number dropped to fewer than 5 per day and on April 14, 2012 for the first time in over 3 years there were no killings in the country.[39] Overall, there were 411 killings in the month of January 2012 but in March the number was 188, more than a 40% reduction in crime.[40] All of this happening while crime in neighboring Honduras has risen to an all-time high.[41] Citizen and foreign women and girls have been victims of sex trafficking in El Salvador. They are raped and harmed, both physically and psychologically, in locations throughout the country.[42][43][44][45][46]

Violent crimes including armed robbery, banditry, assault, kidnapping, sexual assault, and carjacking are common, including in the capital, San Salvador. Downtown San Salvador is dangerous, particularly at night. San Salvador hosts some of the most notorious unified crime family transnational gangs that spread across the Central American heart region, like the Mara Salvatrucha and the 18th Street gang that arrived during and since the Salvadoran Civil War.

The security situation has taken a downturn in San Salvador; in 2002, there were over 9000 intentional homicides in the city of San Salvador by international global Central American Gangs or Maras. 2005 and 2006 saw a worsening security situation in San Salvador; and corruption, with the trend continuing in 2008. Crimes have increased to 13 daily, with this sharp increase having occurred in the last six years, making the words San Salvador City synonymous with crime. The portrayal of San Salvador was a dark and foreboding metropolis rife and reign with crime, grime, corruption, and a deep-seated sense of urban decay, ultimately a vice city.

After the civil war and left in complete ruins and destruction, people described and called the city "San Salvador La Ciudad Que Se Desmorona", "San Salvador The City That Crumbles". San Salvador is a rampant and recurring corruption within the city's civil authorities and infrastructure. Certain locations disputed by rival gangs especially in poor slums on the outskirts areas of San Salvador City are labeled as No man's land.

High-level corruption in El Salvador is a serious problem. President Mauricio Funes pledged to investigate and prosecute corrupt senior officials when he took office in June 2009, but after a political truce with his predecessor, Antonio Saca, who was expelled from the ARENA party amid large-scale corruption allegations, Funes showed an unwillingness to tackle the problem. ARENA alleged that $219 million in government funds under Saca's personal control had disappeared.[47] Saca's own former political allies in the ARENA party and private sector told the U.S. Embassy in San Salvador of widespread abuse of power for personal financial gain. Such corruption, the U.S. Embassy reported in a leaked diplomatic cable, "went beyond the pale" even by Salvadoran standards.[48]

Guatemala

Guatemala's criminal organizations, some of which have been in operation for decades, are among the most sophisticated and dangerous in the Americas. They include former members of the military, intelligence agencies and active members of the police.[49]

Violence against indigenous people

Guatemala is home to 24 principal ethnic groups. Although the Government of Guatemala has adopted the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the country’s indigenous peoples continue to face a number of challenges.[50]

Every day 33 people become entrapped in sex trafficking rings in Guatemala, including a “shocking” proportion of children, some of them sold into the sex trade by their mothers, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) said. Nearly 60 percent of the 50,000 victims of sex trafficking in Guatemala are children, according to a report by UNICEF and the U.N. Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), which estimates the industry to be worth $1.6 billion a year.[51] In 2009, Guatemala enacted an anti-trafficking law, with rules to be executed in 2014, with a guide developed to assist victims and help fight the online sex trade.[52][44][53]

Women in Guatemala's largest female-dominated labor sectors face persistent sex discrimination and abuse. Domestic workers, many of whom come from Guatemala's historically oppressed indigenous communities, do not have the legal right to be paid the minimum wage. They also have no right to an eight-hour work day or a forty-eight hour work week, have only limited rights to national holidays and weekly rest, and by and large are denied the right to employee-paid health care under the national social security system.In order to get a job in a factory, women must often reveal whether they are pregnant, either through questions on job applications, in interviews, or through physical examinations. Workers who become pregnant after being hired are often denied the full range of maternity benefits provided for in Guatemalan law. And the maquilas routinely obstruct workers' access to the employee health care system to which they have a right - with a direct impact on working women's reproductive health.[54]

Honduras

Crime is a major problem in Honduras, which has the highest murder rate of any nation. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Honduras has the highest rate of intentional homicide in the world, with 6,239 intentional homicides, or 82.1 per 100,000 of population in 2010. This is significantly higher than the rate in El Salvador, which at 66.0 per 100,000 in 2010, has the second highest rate of intentional homicide in the world.[55]

According to the International Crisis Group, the most violent regions outside of the major urban areas in Honduras exist on the border with Guatemala, and are highly correlated with the many active drug trafficking routes plying the region.[56]

Mexico

Crime is among the most urgent concerns facing Mexico, as Mexican drug trafficking rings play a major role in the flow of cocaine, heroin, and marijuana transiting between Latin America and the United States. Drug trafficking has contributed to corruption, which has had a deleterious effect on Mexico's Federal Representative Republic. Drug trafficking and organized crime have also been a major source of violent crime in Mexico. Mexican citizens and foreigners have been victims of sex trafficking in Mexico. Drug cartels and gangs fighting in the Mexican War on Drugs have relied on trafficking as an alternative source of profit to fund their operations.[57][58][59][60] The cartels and gangs also abduct women and girls to use as their personal sex slaves.[57]

Mexico has experienced increasingly high crime rates, especially in major urban centers. The country's great economic polarization has stimulated criminal activity in the lower socioeconomic strata, which include the majority of the country's population. Crime continues at high levels, and is repeatedly marked by violence, especially in the cities of Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez, and the states of Baja California, Durango, Sinaloa, Guerrero, Chihuahua, Michoacán, Tamaulipas, and Nuevo León.[61] Other metropolitan areas have lower, yet still serious, levels of crime. Low apprehension and conviction rates contribute to the high crime rate.

Before the drug war in Mexico, there were roughly 300 murders in the border city of Ciudad Juarez in 2007. In 2010, state officials reported a peak of 3,622 homicides in the city. With a rate of 272 murders per 100,000 residents, Ciudad Juarez alone had the highest murder rate in the world, although the rate has steadily decreased since then to reach only 300 murders in 2015.[62]

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico has become a major transshipment point for illegal drugs that are smuggled from source countries like Colombia and Peru into the U.S. mainland. Most of it is transported to and through the island from drug trafficking organizations in the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Florida, and criminal organizations in Puerto Rico.[63] One of the most common ways drugs are smuggled into the island is through commercial and private maritime vessels, and container terminals such as the Port of San Juan. It is the busiest port in the Caribbean and the second busiest in Latin America.

Because drugs are trafficked directly into the island from other source countries, they are less expensive than in any other place in the United States. Thus, it is cheap and easy for street gangs to buy and deal to the public mostly in, and from, housing projects, leading to turf wars and the second highest homicide rate in the United States. Police undermining in the drug trade and corruption are also common. Between 1993 and 2000, 1,000 police officers in Puerto Rico lost their jobs from the department due to criminal charges and between 2003 and 2007, 75 officers were convicted under federal court for police corruption.[64] 2011 was marked as the most violent year for Puerto Rico with approximately 1,120 murders recorded, 30.5 homicides per 100,000 residents.

Venezuela

Venezuela is among the most violent places in Latin America. Class tension has long been a part of life in the South American country, where armed robberies, carjackings and kidnappings are frequent. Venezuela was ranked the most insecure nation in the world by Gallup in 2013 with the United Nations stating that such crime is due to the poor political and economic environment in the country.[65][66] As a result of the high levels of crime, Venezuelans were forced to change their ways of life due to the large insecurities they continuously experienced.[67]

Crime rates are higher in 'barrios' or 'ranchos' (slum areas) after dark. Petty crime such as pick-pocketing is prevalent, particularly on public transport in Caracas. The government in 2009 created a security force, the Bolivarian National Police, which has supposedly lowered crime rates in the areas in which it is so far deployed according to the Venezuelan government, and a new Experimental Security University was created.[68] However, many statistics have shown an increase of crime even after such measures were taken, with the 2014 murder rate showing an increase to 82 per 100,000, more than quadrupling since 1998.[69][70] The capital Caracas has one of the greatest homicide rates of any large city in the world, with 122 homicides per 100,000 residents.[71] Venezuela has also ranked high internationally among countries with high kidnapping rates, with consulting firm Control Risk ranking Venezuela 5th in the world for kidnappings in 2013[72] and News.com.au calling Venezuela's capital city of Caracas "the kidnap capital of the world" in 2013, noting that Venezuela had the highest kidnapping rate in the world and that 5 people were kidnapped for a ransom every day.[73]

Foreign governments have also advised tourists of safety concerns while visiting the country. The United States State Department and Government of Canada has warned foreign visitors that they may be subjected to robbery, kidnapping for a ransom or sale to terrorist organizations and murder, and that their own diplomatic travelers are required to travel in armored vehicles.[74][75] The United Kingdom's Foreign and Commonwealth Office has advised against all travel to Venezuela.[76]

See also

- Crime in Mexico

- Homicide in world cities

- Illegal drug trade in Latin America

- List of Brazilian states by murder rate

- List of cities by murder rate

- List of countries by firearm-related death rate

- List of countries by incarceration rate

- List of countries by intentional death rate - homicide plus suicide.

- List of countries by intentional homicide rate

- List of countries by life expectancy

- List of countries by suicide rate

- List of federal subjects of Russia by murder rate

- List of Mexican states by homicides

- List of U.S. states and territories by violent crime rate

- List of U.S. states and territories by intentional homicide rate

- List of United States cities by crime rate (2012)

- Social cleansing

- United States cities by crime rate (100,000–250,000)

- United States cities by crime rate (60,000-100,000)

Notes and references

- ↑ World Bank research convincingly demonstrates a strong link between crime and income inequality, which has worsened in Latin America in the past decade and is unlikely to improve dramatically in the years ahead. - Prillaman (2003:1)

- ↑ "Latin America Is the Murder Capital of the World". The Wall Street Journal. 20 September 2018.

- ↑ Cesar Chelala, Violence in the Americas: The Social Pandemic of the 20th Century (Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization, 1997).

- 1 2 "LAII: Crime, Violence and Democracy in Latin America". Archived from the original on November 3, 2007.

- ↑ Latin America and Caribbean - Crime, Violence, and Development: Trends, Costs, and Policy Options in the Caribbean

- ↑ "Violent crime has undermined democracy in Latin America". Financial Times. 9 July 2019.

- ↑ "Global Corruption Barometer - Latin America & the Caribbean 2017". Transparency.org. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- ↑ Violence and Crime in Latin America (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016, retrieved 28 August 2013

- ↑ "Amnesty International: Latin America 'dangerous' for journalists", CNN, 13 May 2011, retrieved 30 August 2013

- ↑ "Latin America What I want to Change". prezi.com.

- ↑ "Emergency Medical Help". www.emergency.com.

- ↑ Rafael Romo and Nick Thompson, Inside San Pedro Sula, the 'murder capital' of the world, CNN, March 28, 2013, accessed April 30, 2013.

- ↑ Carol Kuruvilla, San Pedro Sula in northwest Honduras is the murder capital of the world: report, New York Daily News, March 30, 2013, accessed April 30, 2013.

- ↑ Jorge Cabrera, Life and death in the murder capital, Reuters, April 5, 2013, accessed April 30, 2013.

- ↑ Honduran City is World Murder Capital; Juarez Drops for Second Year in a Row, Fox News Latino, February 8, 2013, accessed April 30, 2013.

- 1 2 "InSight Crime's 2016 Homicide Round-up". insightcrime.org. 16 January 2017.

- ↑ Crime Hinders Development, Democracy in Latin America, U.S. Says, retrieved 29 August 2013

- ↑ Gangs and Crime in Latin America, DIANE, ISBN 9781422332887, retrieved 29 August 2013

- ↑ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DEC/Resources/Crime&Inequality.pdf FAJNZYLBER et al, "Inequality and law", Journal of Law and Economics, vol. XLV (April 2002)

- ↑ Crime Hinders Development, Democracy in Latin America, U.S. Says - US Department of State Archived 2008-02-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The Bolivarian Government of Hugo Chávez: Democratic Alternative for Latin America? (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2013, retrieved 29 August 2013

- 1 2 Gangs and Crime in Latin America, DIANE, ISBN 9781422332887, retrieved 29 August 2013

- ↑ Transforming Armed Forces to National Guard Units in Latin America, retrieved 29 August 2013

- ↑ Thompson, Ginger (26 September 2004), "Shuttling Between Nations, Latino Gangs Confound the Law", The New York Times, retrieved 29 August 2013

- ↑ WC Prillaman (2003), "Crime, democracy, and development in Latin America," Policy Papers on the Americas

- ↑ see Daniel Lederman, Norman Loayza, and Ana María Menendez, “Violent Crime: Does Social Capital Matter?” Economic Development and Cultural Change 3 (April 2002): 509–539; Richard Rosenfeld, Steven F. Messner, and Eric P. Baumer, Social Capital and Homicide (Saint Louis:University of Missouri Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 1999).

- ↑ __."Crime Hinders Development, Democracy in Latin America, U.S. Says". U.S. Department of State's Bureau of International Information Programs. April 2005. < "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)> (accessed May 19, 2008). - ↑ "BRAZIL: Youth Still in Trouble, Despite Plethora of Social Programmes Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine". IPS. March 30, 2007.

- ↑ Brazil – Country Brief

- ↑ "A Year of Violence Sees Brazil's Murder Rate Hit Record High". The New York Times. 10 August 2018.

- ↑ "Homepage". Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- ↑ "Violence in the Brazilian Favelas and the Role of the Police | Office of Justice Programs". www.ojp.gov. Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- ↑ Thiago, Alves (March 23, 2023). "Violent gangs in Brazil attack rock-tourist region in the Northeast". www.brazilreports.com.

- ↑ "Q&A: Colombia's civil conflict". BBC News. December 23, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ List of countries by intentional homicide rate

- ↑ "Colombia kidnappings down 92% since 2000, police say". bbc.com. 28 December 2016.

- ↑ "Military Personnel – Logros de la Política Integral de Seguridad y Defensa para la Prosperidad" (PDF) (in Spanish). mindefensa.gov.co. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-13.

- ↑ "In El Salvador, the Murder Capital of the World, Gang Violence Becomes a Way of Life - ABC News". ABC News. May 17, 2016. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016.

- ↑ "El Salvador celebrates murder-free day". ABC News. 16 April 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ Archibold, Randal C. (24 March 2012). "Homicides in El Salvador Drop, and Questions Arise". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Honduras among world's most dangerous places - News". Jamaica Observer. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ "Human Trafficking and the Children of Central America". IPS. August 21, 2019.

- ↑ "Gang Involvement in Human Trafficking in Central America". IPS. September 6, 2019.

- 1 2 "Human trafficking of girls in particular "on the rise," United Nations warns". CBS News. January 30, 2019.

- ↑ "Music video against human trafficking and sexual exploitation launched in El Salvador". IOM. March 8, 2012.

- ↑ "My Story Bringing the Light of Jesus to Sex-Trafficked Women of El Salvador". CLD News. 2020.

- ↑ United States Embassy San Salvador, "ARENA Expels Former President Saca," classified diplomatic cable CONFIDENTIAL, 15 December 2009, WikiLeaks ID #240031 Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ United States Embassy San Salvador, "Reorganizing ARENA: The Party's Future After Avila's Defeat," classified diplomatic cable SECRET/NOFORN, 6 October 2010, WikiLeaks ID #228629 Archived 3 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Guatemala Organized Crime News".

- ↑ "Indigenous World 2020: Guatemala - IWGIA - International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs". www.iwgia.org.

- ↑ "Guatemala 'closes its eyes' to rampant child sex trafficking: U.N." Reuters. June 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Sex trafficking in Guatemala involves primarily children, UNICEF report finds". Fox News. June 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Central America – Fertile Ground for Human Trafficking". IPS. November 8, 2019.

- ↑ "Guatemala: Women and Girls Face Job Discrimination". Human Rights Watch. February 11, 2002.

- ↑ This increased further to 7,104 homicides in 2011. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2011), 2011 Global Study on Homicide - Trends, Context, Data (PDF), Vienna, Austria: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, p. 93, Table 8.1, retrieved 30 March 2012

- ↑ International Crisis Group. "Corridor of Violence: The Guatemala-Honduras Border". CrisisGroup.org. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- 1 2 "The Mexican Drug Cartels' Other Business: Sex Trafficking". Time. July 31, 2013.

- ↑ "Tenancingo: the small town at the dark heart of Mexico's sex-slave trade". The Guardian. April 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Human trafficking survivors find hope in Mexico City". Deseret News. July 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Hiding in plain sight, a hair salon reaches Mexican trafficking victims". The Christian Science Monitor. April 12, 2016.

- ↑ "El narco se expande en México". New America Media. Archived from the original on November 25, 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ↑ "Termina 2015 con 300 homicidios; disminuye violencia en 23% del 2014". Juarez Noticias. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ↑ National Drug Intelligence Center. "Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands Drug Threat Assessment." U.S. Department of Justice. (2003). print.

- ↑ "Police corruption undermines Puerto Rican drug war." Miami Herald [Miami, FL] 18 July 2007. General OneFile. Web. 7 June 2010.

- ↑ Sonnenschein, Jan (19 August 2014). "Latin America Scores Lowest on Security". Gallup. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela es el país más inseguro del mundo, según un estudio". El Espectador. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ↑ "Insecurity has changed the way of life". El Tiempo. 27 April 2014. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ↑ Simon Romero. "Venezuela more deadly than Iraq". New York Times. August 24, 2010

- ↑ "Venezuela Ranks World's Second In Homicides: Report". NBC News. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Crime in Venezuela: Shooting the messenger". The Economist. 2010-08-18. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ↑ "Venezuela Country Specific Information". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ Molina, Thabata (14 December 2013). "Ubican a Venezuela en el quinto lugar en riesgo de secuestros". El Universal. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ↑ "Welcome to Venezuela, the kidnap capital of the world". News.com.au. 13 November 2013. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Travel Warning". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela". Government of Canada. 16 November 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ↑ "FCO travel advice mapped: the world according to Britain's diplomats". The Guardian.

.svg.png.webp)