| Corrientes campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Paraguayan War | |||||||

The Battle of Butuí in L'Illustration, Volume XLVI, Paris, 1865 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Minor losses[3] | 30,000 dead from disease, 8,500 killed or missing, and 10,000 captured[3] | ||||||

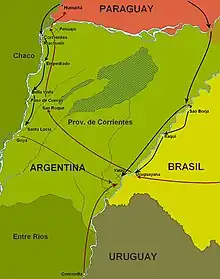

The Corrientes campaign or the Paraguayan invasion of Corrientes was the second campaign of the Paraguayan War. Paraguayan forces occupied the Argentinian city of Corrientes and other towns in Corrientes Province. The campaign occurred at the same time as the Siege of Uruguaiana.

Argentina and Uruguay declared war against the Paraguayan invaders, who were already at war with the Empire of Brazil, and signed the Treaty of the Triple Alliance. The Paraguayan invasion of Argentina failed, but led to the invasion of Paraguay in later campaigns.

Background

Military situation

In the early 1860s, liberal parties took power during civil wars in Argentina and Uruguay. In Argentina, General Bartolomé Mitre assumed the presidency in 1862.[4] Mitre and Uruguayan General Venacio Flores were allied with the Empire of Brazil, and Flores launched a rebellion to take power with Brazilian and Argentinian support.

Faced with the advance of liberal forces backed by the empire, the conservative Paraguayan government of Marshal Francisco Solano López anticipated that Brazil and Argentina would try to incite a civil war in Paraguay. Solano Lopez, on the other hand, wanted to influence the other countries in the Río de la Plata basin.

The Brazilian- and Argentinian-backed invasion of Uruguay by Flores motivated López to demand the withdrawal of foreign forces from Uruguay at the Uruguayan government's request. The Paraguayan invasion of Mato Grosso was a success, but the Partido Blanco government in Uruguay was defeated and General Flores assumed the presidency.

López asked Argentinian president Bartolomé Mitre to allow his troops to cross Corrientes Province towards the Uruguay River to restart the civil war in Uruguay and attack the Brazilian province of Rio Grande do Sul. López told Mitre that Argentina was neutral in the conflict between Paraguay and Brazil (as it had been in the Uruguayan Civil War) and, since he had allowed Uruguayan rebel troops and the Brazilian navy to cross Argentine territory and jurisdictional waters, López could expect the same authorization for Paraguayan troops going to Brazil or Uruguay. Mitre refused, saying that he could not allow the passage of troops through his territory and remain neutral.

Plans

Paraguay invaded and occupied Mato Grosso, although Brazil had claimed some of that territory. Paraguay had little or no communication with the rest of Brazil, so Paraguayan troops could not further advance into Brazil to force it to surrender or negotiate. For results in Uruguay or to prevent further attacks on Paraguayan territory, it had to continue the war in the province of Rio Grande do Sul.

Before Mitre's refusal, López had planned to concentrate his forces along the Uruguay River to attack Brazil or enter Uruguayan territory. When war was declared on Argentina, however, he needed to prevent the Argentine Army from hindering the Paraguayan advance with a diversionary maneuver along the Uruguay River. The objective was to occupy the city of Corrientes, a strategy that would also make it possible to control the upper Paraná River, leaving communications open through Corrientes Province.

Between the decision to invade and the troop advance, López decided to use troops occupying the capital of the invaded province to support the passage on the Uruguay River. Instead of concentrating most of the troops in this last column, he formed an army of only about 12,000 men and sent 25,000 soldiers to the Paraná River.

Before implementing his plan, López sent Lieutenant Cipriano Ayala to deliver the declaration of war to Buenos Aires. War was declared on 18 March 1865, and was published in Asunción a week later. The attack would be launched after the expected delivery date of the declaration of war but before the news arrived back in Paraguayan territory to give the disorganized, under-equipped Argentine army no time to react. The messenger carrying the declaration of war met with many obstacles, however, and the Argentine public learned about the invasion of Corrientes before it heard about the declaration of war.

Occupation of Corrientes

At dawn on 13 April 1865, a squadron of five Paraguayan steamboats appeared at the city of Corrientes with a landing party of 2,500 under the command of Commander Pedro Ignacio Meza. They passed the city headed south, then turned north and attacked the Gualeguay and the 25 de Mayo (Argentine steamers in port for repairs); the 25 de Mayo had a crew of 80 men. The crews of two Paraguayan ships boarded the Argentine ships, and captured them after a skirmish with some casualties. About 3,500 to 4,000 men landed and occupied the city the following day.

After the attack, residents led by Desiderio Sosa constructed a defense on the roofs of houses closest to the port. The attacking fleet withdrew, and an attempt was made to organize battalions under Colonel Solano González; volunteers were summoned to the Plaza 25 de Mayo and the Plaza del Mercado.[5]

Paraguayan general Wenceslao Robles had settled in Paso de la Patria with more than three thousand men, awaiting the Paraguayan fleet after it attacked Corrientes. Robles loaded as many soldiers as he could; the small Paraguayan squadron returned to Corrientes at dawn on 14 April, taking possession of the city square without any resistance. Shortly afterward, the column from Paso de la Patria arrived under Robles and the rest of the invading forces. The 25 de Mayo and Gualeguay did not return to Corrientes, since they had been incorporated into the Paraguayan Navy and sent to Asunción for repairs.[6]

The Argentine authorities withdrew with the few battalions, which could not resist the invading Paraguayan forces. Withdrawing to the interior was their only option to reorganize under Nicanor Cáceres, who harassed the invaders and kept the troops loyal to Governor Manuel Lagraña.[7]

Corrientes reacted in two different ways. Some residents fled to rural areas away from the city, to country houses in Lomas; others crossed the Paraná and took refuge in the interior of the Chaco Territory. The rest, a significant fraction of the population, did not resist the Paraguayan troops. A contemporary chronicler wrote that the city's inhabitants were not hostile to the invaders, which made it easier for them to receive good treatment (unlike the abusive treatment carried out in other occupied territories).[6]

Paraguayan control of the square was irreversible in principle, so Governor Lagraña, his closest collaborators, and security groups moved to rural areas to avoid being taken prisoner. Before he withdrew, Lagraña ruled that every citizen of Corrientes between sixteen and seventy years of age was required to enlist and fight the occupation forces.[6]

In the afternoon, a column of 800 cavalry arrived by land and entered the city. Robles met with a popular assembly apparently consisting of members of the Federalist Party and other opponents of the national government. A provisional government was formed by Teodoro Gauna, Víctor Silvero and Sinforoso Cáceres. Local political action was carried out by Cáceres, but the triumvirate was limited to endorsing the activities of the Paraguayan commissioners José Berges, Miguel Haedo and Juan Bautista Urdapilleta in commercial matters and relations with Paraguay.

The Federalist Party leaders in the capital initially supported the Paraguayan occupation as allies in their attempt to recover the political dominance they had lost at the end of 1861 after the Battle of Pavón and the Corrientes revolution. Colonel Cayetano Virasoro stood out, although he was later accused of collaborating with the Paraguayans. The Paraguayan troops continued to receive reinforcements, reaching just over 25,000 men over the following days.

Lagraña assembled the province's population and summoned all males between 17 and 50 years of age to arms. He entrusted Colonel Desiderio Sosa with the military organization of the capital and its surroundings, and settled in the nearby town of San Roque. Lagraña gathered about 3,500 volunteers, many of whom had no military experience and very little equipment. He was joined a few weeks later by General Nicanor Cáceres, who arrived from the Curuzú Cuatiá area and contributed about 1,500 men (almost all veterans).

The presence on the governor's side of Cáceres, who (despite his ambiguous record) was considered to belong to the Federalist Party, cooled federal enthusiasm for the invaders and deprived them of provincial support. As the Paraguayan army began its advance south, Lagraña and his army had to withdraw to Goya.

In the early hours of 11 July 1865, Paraguayan soldiers kidnapped Toribia de los Santos, Jacoba Plaza, Plaza's son Manuel, Encarnación Atienza, Carmen Ferré Atienza and her daughter Carmen, Victoria Bar and wives of the Corrientes resistance leaders from their homes. The occupation of Corrientes was difficult for its inhabitants. In his essay La toma de Corrientes, Wenceslao Domínguez wrote:

The slightest suspicion was enough for summary trial if there was one, and the slightest reason for Argentine patriotism was punished with the death penalty. It would be long to detail the conditions of the gloomy outing in Corrientes; and besides, it is also quite well known.

In his book Historia ilustrada de la provincia de Corrientes, historian Antonio Emilio Castello wrote:

The city of Corrientes dragged out a miserable existence immersed in fear of accusations, abuses, and captivity in Paraguayan prisons. One day the invaders carried out a ferocious massacre of the Chaco Indians in the streets of Corrientes. The poor Indians had been selling firewood and grass for years, from house to house. As some of them refused to receive Paraguayan paper money, they were exterminated with sabers and bullets in broad daylight.

Argentine reaction

_pour_l'arm%C3%A9e_d'op%C3%A9ration._-_D'apr%C3%A8s_les_croquis_envoy%C3%A9s_par_M._Paranhos_Junior.jpg.webp)

The population of the big cities denounced the invasion, which they saw as unjustified and treacherous. President Mitre's speech, delivered the day that news of the attack arrived in Buenos Aires, included the later-reviled phrase "In 24 hours to the barracks, in fifteen days in Corrientes, in three months in Asunción!" and fueled the desire for revenge. Many young men rushed to enlist in regiments created for the war. The same thing happened in Rosario, and to a lesser extent in Córdoba and Santa Fe. The reaction in the rest of the country was very different; only the most determined supporters of the ruling party publicly opposed the Paraguayan attack.

Entre Ríos Province opposed the national government. Respecting his previous commitments, governor and former president Justo José de Urquiza assembled a provincial army of 8,000 men and moved it to the northern border of the province. When they reached Corrientes in July 1865, soldiers who had believed that they were going to fight on the Paraguayan side rose up in the Disbandment of Basualdo and deserted en masse. The central government refrained from reprisals against the rebels. Urquiza recruited about 6,000 soldiers from the provincial forces who had a reputation as excellent cavalry troops, but they disbanded in the Disbandment of Toledo in November 1865. This second rebellion was harshly repressed with the help of Brazilian and Uruguayan troops.[8]

On 1 May, the Treaty of the Triple Alliance was signed by Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil. The speed with which an agreement was reached makes a number of historians suspect that the treaty had been prepared in advance.

Mitre gathered the available troops in Buenos Aires, Rosario, and San Nicolás de los Arroyos, and moved a strong division north aboard the war fleet. He ordered each provincial government to provide a large contingent of infantry forces to reinforce the enlisted troops. Most of the cavalry who served in the frontier forts with indigenous people in the south of the country were also sent north.

Paraguayan advance

In late April, the Paraguayan army slowly advanced south along the Paraná River and seized Bella Vista, Empedrado, Santa Lucía, and Goya. During the advance, the Corrientes forces engaged in guerrilla warfare and established ambush points on the roads. Battles at Caá Catí and Naranjito consolidated the route along the rivers, since the center and south of Corrientes Province remained under government control with a new capital in San Roque. In a battle on 10 May, Colonel Fermín Alsina led 800 men and was defeated by about 5,000 Paraguayans. In the Battle of Palmira nine days later, Colonel Manuel Vallejos realized that the Paraguayan troops could not confront an organized army. That battle and the Battle of Corrientes, led by General Wenceslao Paunero, were crucial to stopping the Paraguayan troops on the Paraná. San Roque, from which the governor of Corrientes exercised local power, prevented movement towards the center. The Imperial Brazilian Navy, in control of the Paraná River, prevented assistance by water.

Part of the Allied squadron arrived at Corrientes on 25 May, with 725 men led by Paunero. The four battalions were commanded by Juan Bautista Charlone, Ignacio Rivas, and Adolfo Orma; Manuel Rosetti, with an artillery squad, was also part of the division.

Charlone's battalion attacked without waiting for reinforcements, interposing themselves between the fleet and the Paraguayan defenders and preventing the use of artillery. When the other battalions landed, the Argentines advanced towards the city in street-by-street fighting. The Paraguayans were defeated and expelled from the city, with about 400 dead; the Argentines had 62 dead and dozens wounded.

The Paraguayans, commanded by Major José del Rosario Martínez, withdrew towards Empedrado to reorganize and receive reinforcements; a large division was advancing from Paso de la Patria toward the capital. General Cáceres refused to advance in support of the Argentinians despite the insistence of General Manuel Hornos, who had joined his forces with cavalry. Although this decision made it difficult for Paunero's men to resist the expected counterattack, their presence in the south of the province prevented the Paraguayan division which had occupied Goya and Santa Lucía from advancing to support the Uruguay River.

Without prior warning or taking advantage of his military position, Paunero left with his troops at dawn on the 27th. At the request of Governor Lagraña and General Hornos, Paunero agreed to land in the south of the province at the town of Esquina.

The Paraguayan troops subjected the population to violent repression because they suspected them of aiding Paunero's troops. On 11 July, they took five wives of resistance leaders hostage and brought them to Paraguayan territory. Four returned in 1869 after harsh treatment, but Colonel Desiderio Sosa's wife died in Asunción.

Battle of Riachuelo

A Brazilian squadron was stationed near the city of Corrientes, blocking the Paraguayan fleet from the Paraná. The squadron consisted of nine ships, almost all battleships, commanded by Francisco Manuel Barroso.

Marshal López organized a plan of attack on the Brazilian fleet which consisted of attacking and boarding the enemy fleet by surprise and bombarding fleeing ships from the shore. The Paraguayan squadron consisted of nine steamships. That fleet's only ironclad warship, commanded by Pedro Ignacio Meza, transported 500 infantrymen for the boarding maneuver. They also moved a large number of wooden barges, each with a cannon aboard. The Paraguayans passed the Argentine fleet, protected by darkness and an island, before going upriver and attacking with grapeshot, muskets, and sabers.

A battery commanded by Major José María Bruguez, hidden in the forests of ravines north of the mouth of the Riachuelo, was to bombard ships fleeing the ambush. To the south were 2,000 Paraguayan riflemen, also hidden in the woods at the top of the ravine.

The operation began during the night of 10–11 June. As they neared the objective, the boiler of one of the Paraguayan ships broke and Meza insisted on repairing it. When he decided to go ahead with only eight ships, it was morning and he had lost the element of surprise. Meza's fleet passed the Argentine squadron, and cannon fire was exchanged.

._-_D'apr%C3%A8s_un_dessin_envoy%C3%A9_par_M._F%C3%A9lix_Vogeli.jpg.webp)

Meza reached the outskirts of the Riachuelo and docked in the ravine. The Brazilians closed in on him, but coastal artillery caused serious damage and stranded a Brazilian ship.

Barroso then rammed and sank three Paraguayan ships with his flagship, the frigate Amazonas, and Brazilian artillery disabled the wheels of two Paraguayan steamers. Three Brazilian ships sank several wooden barges, and most of the Paraguayan fleet was in ruins.

The Brazilian fleet did not take advantage of the victory; the next day, it set off downstream towards the outskirts of Emedrado after preventing communications between Paraguay and the Atlantic Ocean.[9] The Paraguayan defeat prevented its column on the Paraná River from aiding the one on the Uruguay River, and the victory at Riachuelo raised the morale of the Argentine troops.

Uruguay campaign

While the city of Corrientes was occupied, a garrison of 12,000 men commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Antonio de la Cruz Estigarribia headed east of the province to attack Brazilian territory on the Uruguay River. President Mitre appointed General Urquiza, Governor of Entre Ríos, commander of the vanguard division with the mission of confronting the Uruguayan column. Estigarribia divided his troops and sent Major Pedro Duarte, at the head of a small advance column, to occupy the town of Santo Tomé on 5 May. Estigarribia entered Santo Tomé four days later and began crossing the Uruguay River at the head of about 6,500 troops, leaving the rest divided between the Santo Tomé garrison and Duarte's advance guard of just over 3,000 soldiers.

Estigarribia advanced south without resistance, occupying São Borja and Itaqui. A Paraguayan regiment was attacked and partially destroyed near São Borja in the Battle of Mbuty. Some Paraguayan forces remained as a garrison in São Borja, while Duarte headed south. Basualdo's disbandment occurred on 4 July when Urquiza's troops refused to fight against Paraguay, whom they considered their ally.

General Venancio Flores, president of Uruguay since his triumph over the Blanco Party, joined Urquiza at the head of 2,750 men. The 1,200-strong Brazilian force, under Lieutenant Colonel Joaquim Rodrigues Coelho Nelly, headed towards Concordia. Flores had 4,540 men, a force he considered insufficient to face the two Paraguayan columns.

Flores, Duarte and Estigarribia marched slowly to meet each other. Paunero's 3,600 men began an accelerated march through estuaries and rivers, rapidly crossing the south of the province of Entre Ríos, to join Flores. An additional 1,400 cavalry from Corrientes under General Juan Madariaga also marched there. Colonel Simeón Paiva, with 1,200 men, closely followed Duarte's column with orders not to attack.

Estigarribia rejected the opportunity to destroy his enemies one by one and disobeyed López's orders, which told him to continue to Alegrete.[10] He entered Uruguaiana on 5 August, reorganizing and supplying his forces without supporting Duarte. General David Canabarro's Brazilian forces, too few to attack Estigarribia's 5,000-man garrison, remained near the town without being attacked by the Paraguayan chief. On 2 August, Duarte occupied present-day Paso de los Libres.

Battle of Yatay

With the numerical superiority of the allies, Duarte unsuccessfully asked Estigarribia for help.[11] On 13 August, without Duarte able to prevent allied attacks, Paunero and Paiva joined Flores' army with about 5,550 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 32 artillery pieces. Duarte had 1,980 infantry, 1,020 cavalry, and no artillery.

Duarte left Paso de los Libres and took up position in the ravines of the Yatay near the town. His defensive position was good, but retreat would be impossible in the event of defeat.[12]

The battle began at ten a.m. on 17 August with a hasty attack by Palleja's infantry division; Duarte took advantage of the error and counterattacked with almost all his cavalry, causing hundreds of casualties and forcing Palleja to fall back. The artillery fired only 50 shots before having to cease fire, because Palleja's retreating division had crossed the line of fire.[13]

Ignacio Segovia's cavalry division attacked the Paraguayan cavalry in a battle lasting over two hours. When the Allied infantry then overwhelmed the Paraguayan positions, the Paraguayans held out for another hour. Duarte attempted a cavalry charge, but his horse was killed and he was taken prisoner by Paunero. He later saved Duarte's life after Flores intended to have him executed.[14] Some infantry continued to resist north of the Yatay, but were defeated by Juan Madariaga's cavalry from Corrientes.

The Paraguayans had 1,500 dead and 1,600 taken prisoner. Only about a hundred men survived by swimming across the Uruguay and joining Estigarribia's forces. Among the prisoners, Flores found several dozen Uruguayan soldiers (supporters of the Blanco Party who had taken refuge in Paraguay) and federalist Argentines who did not recognize Mitre's national authority. Forgetting the help he had obtained from Brazil and Mitre's rebellion against the Argentine Confederation, Flores ordered their execution as traitors.[15] Many Paraguayan soldiers were forced to take up arms against their own country, replacing allied losses (particularly in the east).[16]

Siege of Uruguaiana

On 16 July, the Brazilian Army reached the border of Rio Grande do Sul and besieged the city of Uruguaiana. The troops received reinforcements, and sent Estigarribia at least three orders to surrender. On 11 September, Emperor Pedro II of Brazil arrived. Presidents Bartolomé Mitre and Venancio Flores were already present, as well as Brazilian military leaders such as the Marquis of Tamandaré and Lieutenant General Manuel Marques de Sousa. The allied armies had 17,346 combatants (12,393 were Brazilian, 3,802 Argentines, and 1,220 Uruguayans), and 54 guns. The surrender took place on 16 September when Estigarribia reached an agreement on the required conditions.

The emperor ordered his officers to place themselves under Mitre, who was appointed commander-in-chief of the allied armies. The head of the Paraguayan division of the allied army wrote to Estigarribia, rejecting his charge of treason and accusing López of betraying his country by oppressing his people. Estigarribia's reply indicated that not all of his officers agreed to fight to the death, as he had said.[17]

On 11 September, with authorization from the besieging forces, Estigarribia sent almost the entire civilian population to the allied camp. His motive was not solely humanitarian, since the civilian population consumed food.

After exchanges of cannonades and rifle shots, Mitre organized an assault on the square on 13 September. The besieged troops died from disease and desertions increased, encouraged by discussions between their leaders about whether they should resist until the end; this reduced the defenders to just over 5,500.

On 18 September, the Marques de Sousa issued an ultimatum that he would begin the assault in two hours. Estigarribia replied that he would hand over the plaza in exchange for the superior officers being allowed to retreat to anywhere, even Paraguay. The Paraguayan soldiers were taken prisoner. Many were killed during the operation, and many others (perhaps 800 to 1,000) were taken prisoner by Brazilian cavalry officers and sold into slavery.[18] Those who remained in the hands of Argentine and Uruguayan officers were forced to become a Paraguayan division of the Allied army or be incorporated into the infantry of those countries. There were 5,574 Paraguayan prisoners: 59 officers, 3,860 infantry, 1,390 cavalry, 115 artillery, and 150 auxiliaries.

Paraguayan withdrawal

Robles ordered his troops to abandon the towns in the south of the province in mid-June, concentrating his forces in the provincial capital. He kept some towns within a 150-kilometre (93 mi) radius of the capital for a time, and cavalry roamed the center of the province.

On 12 August, the Brazilian fleet retreated further south towards Goya. A battery on the coast at Paso de Cuevas, near Bella Vista, bombarded the squadron as it passed. The Brazilian ships were not heavily damaged in the Battle of Paso de Cuevas, although they had 21 dead and 38 wounded (nearly all sailors). The only ship of the Argentine Navy, the Guardia Nacional (commanded by Luis Py, with navy commander José Murature aboard) stopped in front of the battery and engaged in an artillery duel. The ship was damaged, with three dead and 12 wounded. Two of the three soldiers killed by artillery were young officers: one was a son of Captain Py, and the other a son of former Governor Pedro Ferré of Corrientes.

Various commanders of the Allied troops attempted to negotiate with Robles and even induce him to switch sides. As a result, he was replaced by General Francisco Isidoro Resquín on the orders of President López. At the beginning of the following year, Robles would be subjected to a summary trial and executed for his alleged betrayal.

The Paraguayan occupation of Corrientes was now useless, as the Argentine army, reinforced by large Brazilian and Uruguayan contingents, advanced in search of the enemy towards the north. On the other hand, many of the Paraguayan forces were withdrawn towards Paraguayan territory, in anticipation of an Alliance invasion.

At the end of June, and again at the end of July, General Hornos' troops defeated some cavalry groups in the marshes in the center of the province, identified as Argentines, most of them from Corrientes, and with the Federalist Party.

On 21 September, Hornos defeated a division of 810 collaborators from Corrientes under the command of the Lobera brothers from the town of Naranjitos.[19]

Simultaneously, an Allied detachment under the command of General Gregorio Castro advanced along the coast of Uruguay. Passing La Cruz, the vanguard, under the command of Colonel Fernández Reguera, discovered near Santo Tomé an enemy division with three artillery batteries, leading a gigantic herd of 30,000 cattle from Corrientes to their country. Reguera defeated the Paraguayans and advanced to Candelaria, liberating the territory of Alto Paraná.[19]

On 3 October, López ordered Resquín to have the Southern Division evacuate Argentine territory through Paso de la Patria. When the clash between the Argentine forces was already imminent on 22 October, General Resquín evacuated Corrientes by river and by land, and a few days later also withdrew from the last town under their occupation, San Cosimo.

The withdrawal of the Paraguayan forces was accompanied by systematic looting. They looted all the ranches on the Paraná coast, leaving them perfectly clean and setting some of them on fire.[20] Goya suffered especially as the entire commerce of the town suffered unspeakable looting as several steamers on three trips took the loot to Asunción. The national and provincial public offices were found in pieces with their files stolen. The iron materials for the construction of the church were stolen, and a door of the chapel was axed. Farms did not have any livestock and were abandoned by their owners. The looting was perpetrated by the Paraguayans and the Federalist José F. Cáceres, who took his cruelty to the extreme of persecuting the families that had taken refuge in the Chaco.[20] The fates of the other cities were not any better. General Nicanor Cáceres already reported in August that:

the towns of San Roque and Bella Vista that the invaders have occupied for more than two months (...) as well as all the fields through which they have crossed are spoils capable of encouraging the most indifferent.[19]

The provincial capital was occupied by troops of Nicanor Cáceres on the 28th of the same month, and on November 3 the provincial government was reinstalled. That same day, Resquín's 27,000 men completed the passage of the Paraná River to their own country without being hampered by the Brazilians, even taking 100,000 head of cattle across from Corrientes, but most of these died near Itapirú due to the lack of adequate pasture.[21]

On 25 December, a new governor, Evaristo López, was elected by a legislature made up mostly of members of the Federal Party. The Federalist victory was due to the control over most of the provincial territory exercised by General Cáceres, of whom López was a friend and partner. Many collaborators with the Paraguayan invasion who had been arrested and risked being executed for treason, were released thanks to the Federalist government of Corrientes while the others fled to Paraguay.[22] Several of them, among them two of the members of the triumvirate, were executed years later by order of Francisco Solano López.

At the end of the year, the Allied army, gathered in the Ensenadas or Ensenaditas camp, a few kilometers north of Corrientes, near the current town of Paso de la Patria, reached 50,000 men. Just then, the Brazilian fleet took up positions upstream of the confluence of the Paraná and Paraguay rivers.

Battle of Pehuajó

_-_la_19%C2%AA_brigade_br%C3%A9sillienne_command%C3%A9e_par_le_colonel_Willagran-Cabrita_repoussant_l%E2%80%99assaut_des_paraguayens.jpg.webp)

After the withdrawal of the Paraguayan army, the defense of Paraguay focused on two positions. On one side, Fort Itapirú was on the right bank of the Paraná River, defended by a large number of cannons. On the other side, upstream on the Paraguay River, the fortresses of Curuzú, Curupayty and Humaitá prevented the advance of enemy fleets and the land armies up the river.

For their part, the Alliance troops concentrated from December to early April of the following year in the Ensenada camp, north of the city of Corrientes. The meeting of the troops was especially complex since almost all the contingents sent from the provinces of the Argentine interior revolted against being sent to war. For its part, the powerful entrerriana (from Entre Rios) division of 6,000 men, revolted again on 6 November, in the so-called Disbandment of Toledo. Therefore, the Entre Ríos Province was only garrisoned by 400 men, who could not desert due to lack of horses, and whom Urquiza himself had to threaten with execution to force them to embark.[10]

The Paraguayan troops did not just wait for their enemies to advance. They carried out continuous attacks on the coast of Corrientes. They crossed the Paraná River in boats or canoes, without the Brazilians, who could almost see the maneuver, being able to do anything to prevent it. Upon reaching land, cavalry corps from the divisions of Cáceres or Hornos, who were encamped northeast of Ensenaditas, usually came out to confront them. These operations did not come to much except for some cattle theft, at the cost of some deaths; the only positive military effect was discouragement among the Corrientes soldiers, which would not last long.

Finally, on 30 January, Mitre decided to punish the daring Paraguayans, and sent the Buenos Aires division, commanded by General Emilio Conesa, with almost 1,600 men, to meet them. Almost all of them were gauchos from Buenos Aires Province, much more suitable for cavalry than for the infantry to which they were assigned.

The landing party had about 200 men, but on the Paraguayan side there were almost 1,000 more soldiers, who had to cross the next day. After advancing a few kilometers, they reached the Arroyo Pehuajó, where General Conesa was waiting in ambush; before attacking his opponents, he addressed his troops, who burst into loud cheers, betraying their presence to the Paraguayans.

The Paraguayan leader, Lieutenant Celestino Prieto, began to retreat, which Conesa tried to prevent with a massive and direct charge. But the Paraguayans barricaded themselves in the woods behind the stream and took up a defensive position, from which they fired on the Argentine soldiers, who had nowhere to seek shelter. The Paraguayans received around 900 reinforcements, with whom they caused almost 900 casualties in the Argentine forces versus 170 Paraguayans. Just as day fell, General Mitre, who could hear the volleys from his camp, ordered Conesa's troops to withdraw. At nightfall the Paraguayans re-embarked and withdrew at their own expense.

Despite having obtained a victory, the Paraguayan troops did not repeat this type of action.

The last battle before the invasion of Paraguay occurred on 10 April on the island in front of Fort Itapirú, when a Brazilian division took up positions to bombard the fort. The Paraguayans could've limited themselves to exchanging cannon shots, in which they would have had a wide advantage, as they had cover within the walls, while the Brazilians had to defend themselves on a sandy island, with no possible cover. However, the Paraguayans tried to remove their enemy with infantry, and were seriously defeated in their attempt.[23]

Aftermath

On 5 April 1866, the Allied forces captured Fort Itapirú, thus starting the third phase of the war, the Humaitá campaign. The northern front was also practically abandoned, and the northeast section was easily occupied by Brazil, as the Paraguayan troops had to concentrate on the south.

Estigarribia's army was completely lost and Robles's returned with only 14,000 healthy but exhausted soldiers and 5,000 sick. According to George Thompson, by the end of 1865, the Paraguayans had already lost 52,000 men, 30,000 of them on other fronts or due to illness, and 10,000 were sick. During 1864, the Paraguayan army tripled from its original 20,000 troops thanks to massive levies, installing 10,000 in Humaitá, against Argentina, and 15,000 in Villa Encarnación, against Brazil.[24]

The Corrientes campaign had not only been a failure, but led to the formation of the Triple Alliance. It possibly might have formed anyway, as various historians claim, but the invasion precipitated events long before the Paraguayan army was minimally prepared for a war against three countries.

On the other hand, any possible help that could have been obtained from the Argentine Federalists was nullified by Mitre's clever journalistic campaign to present the Paraguayan invasion as a cunning attack with no prior warning. Ultimately, the rebellions of the Federalists, both those of 1865 and the larger Colorados Revolution of 1866, only caused problems for the Argentine Army, and they did not continue to serve in Paraguay at all.

See also

References

- 1 2 Suárez, Martín (1974). Atlas histórico-militar argentino. Buenos Aires: Círculo Militar, p. 277. Cifras de abril de 1865.

- ↑ Corrêa, 2014: 183

- 1 2 Destéfani, Laurio H. (1989). Historia marítima argentina. Buenos Aires: Departamento de Estudios Históricos Navales, pp. 412.

- ↑ Blumenthal, Edward (2019-10-23). Exile and Nation-State Formation in Argentina and Chile, 1810–1862. Springer Nature. p. 11. ISBN 978-3-030-27864-9.

- ↑ Ramírez Braschi, Dardo. Saqueos en la provincia de Corrientes durante la guerra del Paraguay. Temas Americanistas, No. 32, 2014, p. 247-278.

- 1 2 3 Ramírez Braschi, Dardo. Saqueos en la provincia de Corrientes durante la guerra del Paraguay (Looting in the province of Corrientes during the Paraguayan war). Temas Americanistas (Americanist Themes), Number 32, 2014, pp. 247-278.

- ↑ Ramírez Braschi, Dardo. Saqueos en la provincia de Corrientes durante la guerra del Paraguay. Temas Americanistas, Numero 32, 2014, pp. 247-278.

- ↑ Beatriz Bosch, Historia de Entre Ríos, Ed. Plus Ultra, Bs. As., 1991. ISBN 950-21-0108-1

- ↑ Para toda esta sección, véase Tissera, Ramón, Riachuelo, la batalla que cerró a Solano López la ruta al océano, Revista Todo es Historia, número 46, Bs. As., 1971.

- 1 2 Rosa, José María, La guerra del Paraguay y las montoneras argentinas, Ed. Hyspamérica, 1986. ISBN 950-614-362-5

- ↑ José Ignacio Garmendia (1904). Peuser, Bs. As (ed.). Campaña de Corrientes y Río Grande. p. 276.

- ↑ Zenequelli, Lilia, op. cit.

- ↑ Ruiz Moreno, Isidoro, Campañas militares argentinas, No. 4, Ed. Claridad, Bs. As., 2008, pages 70, ISBN 978-950-620-257-6

- ↑ Ruiz Moreno, op. cit., p. 72.

- ↑ Díaz Gavier, Mario, En tres meses en Asunción, Ed. del Boulevard, Córdoba, 2005, p. 38. ISBN 987-556-118-5

- ↑ León de Palleja, Diario de campaña de las fuerzas aliadas contra el Paraguay, Imprenta de El Pueblo, Montevideo, 1865, No I, p. 98.

- ↑ León de Palleja, Diario de campaña de las fuerzas aliadas contra el Paraguay, Imprenta de El Pueblo, Montevideo, 1865, No. I, p. 98.

- ↑ José Ignacio Garmendia, Campaña de Corrientes y Río Grande, Ed. Peuser, Bs. As., 1904.

- 1 2 3 Isidoro J.Ruiz Moreno, Campañas militares argentinas, Tomo IV, p.81.

- 1 2 J. Ruiz Moreno, Campañas militares argentinas

- ↑ Varios miles más de vacunos fueron muertos al no poder cruzarlos. Véase George Thompson, The war in Paraguay, p. 97

- ↑ Véase Horacio Guido, El traidor. Telmo López y la patria que no pudo ser, Ed. Sudamericana, Bs. As., 1998.

- ↑ Zenequelli, op. cit., p. 98.

- ↑ Maligne, Augusto A. (1910). Historia militar de la Républica Argentina durante el siglo de 1810 a 1910. La Nación, p. 110.

Bibliography

- Zenequelli, Lilia, Crónica de una guerra, La Triple Alianza. Ed. Dunken, Bs. As., 1997. ISBN 987-9123-36-0

- Ruiz Moreno, Isidoro J., Campañas militares argentinas, Tomo IV, Ed. Emecé, Bs. As., 2008. ISBN 978-950-620-257-6

- Rosa, José María, La guerra del Paraguay y las montoneras argentinas, Ed. Hyspamérica, 1986. ISBN 950-614-362-5

- Castello, Antonio Emilio, Historia de Corrientes, Ed. Plus Ultra, Bs. As., 1991. ISBN 950-21-0619-9.

- Corrêa Martins, Francisco José (2014). "El empleo de los mitaí y mitá en el ejército paraguayo durante la Guerra de la Triple Alianza (1864-1870)". En Juan Manuel Casal & Thomas L. Whigham. Paraguay: Investigaciones de historia social y política: Actas de las III Jornadas Internacionales de Historia del Paraguay en la Universidad de Montevideo. Asunción: Editorial Tiempo de Historia & Universidad de Montevideo, pp. 181–192. ISBN 9789996760990.

- Giorgio, Dante A., Yatay, la primera sangre, Revista Todo es Historia, Nro. 445, Bs. As., 2004.

- Tissera, Ramón, Riachuelo, la batalla que cerró a Solano López la ruta al océano, Revista Todo es Historia, número 46, Bs. As., 1971.