.jpg.webp) Orsi contrabass saxophone (1999) | |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Single-reed |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 422.212-71 (Single-reed aerophone with keys) |

| Inventor(s) | Adolphe Sax |

| Developed | 1840s |

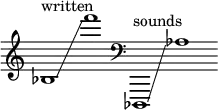

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

|

Sizes:

Orchestral saxophones: Specialty saxophones: | |

| Musicians | |

| See list of saxophonists | |

| Builders | |

| |

The contrabass saxophone is the second-lowest-pitched extant member of the saxophone family proper. It is pitched in E♭ one octave below the baritone saxophone, which requires twice the length of tubing and bore width. This renders a very large and heavy instrument, standing approximately 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) tall and weighing around 20 kilograms (44 lb). Despite this, it was used in marching bands in the early 20th century.

History

The contrabass saxophone was part of the original saxophone family as conceived by Adolphe Sax, and is included in his saxophone patent of 1846, as well as in Kastner's concurrently published Méthode for saxophone. By 1849, Sax was displaying contrabass through sopranino saxophones at exhibitions.[1] Patrick Gilmore's famous American band roster included a contrabass saxophone in 1892, and at least two dozen of these instruments were built by the Evette & Schaeffer company for the US military bands in the early 20th century which, despite their size, were able to played while marching using a strap. Saxophone ensembles were also popular at this time, and the contrabass saxophone was an eye-catching novelty for the groups that were able to obtain one. By the onset of the Great Depression, the saxophone craze had ended, and the contrabass, already rare, almost disappeared from public view.[1]

Construction

The saxophones in Sax's 1846 patent are only folded a maximum of three times, which necessarily requires the lower saxophones (from the baritone downwards) to be progressively taller. The contrabass saxophone follows this pattern, bending upwards at the mouthpiece neck, then bending 180° at the top, and 180° again at the base of the instrument in order to orient the bell upwards and outwards. With a tubing length of nearly 4.9 metres (16 ft), the contrabass is approximately 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) tall. The tubax, invented by German instrument maker Benedikt Eppelsheim in the late 1990s, is a modern solution to this unwieldiness which adds a fourth bend, similar to the layout of a contrabass sarrusophone. This allows the E♭ tubax to cover the same range as the contrabass saxophone, yet stand only 114 centimetres (3 ft 9 in) high, comparable to the baritone saxophone.[2]

In the early 2000s, the contrabass saxophone experienced a resurgence in interest. Although still rare and expensive, three manufacturers now produce contrabass saxophones: Benedikt Eppelsheim (inventor and producer of the tubax), Milan-based instrument maker Romeo Orsi (on request), and Brazil saxophone maker J’Élle Stainer.[3][4][5][6]

Repertoire and performance

Due to its large body and wide bore, the sound of the contrabass saxophone has great acoustical presence and a very rich tone. It can be smooth and mellow, or harsh and buzzy depending on the player, and on the mouthpiece and reed combination used. Its middle and upper registers are warm, full, and expressive. Because its deepest tones vibrate so slowly (as with the contrabassoon or pedal notes on a pipe organ) it can be difficult for listeners to perceive individual pitches at the bottom of its range; instead of hearing a clearly delineated melody, listeners may instead hear a series of rattling tones with little pitch definition. However, when these tones are reinforced by another instrument playing at the octave or fifteenth, they sound clearly defined and have tremendous resonance and presence. In some contemporary jazz/classical ensembles the contrabass saxophone doubles the baritone saxophone either at the same pitch or an octave below, depending on the register of the music.

In classical music

While there are few orchestral works that call specifically for the contrabass saxophone, the growing number of contrabass saxophonists has led to the creation of an increasing body of solo and chamber music literature. It is particularly effective as a foundation for large ensembles of saxophones. As an example, the eminent saxophonist Sigurd Raschèr (1907-2001) played the instrument in his Raschèr Saxophone Ensemble, and it is featured on most of the albums by the Nuclear Whales Saxophone Orchestra. Spanish composer Luis De Pablo wrote Une Couleur in 1988 for a single performer playing six saxophones, including contrabass and sopranino.[7] The Scottish composer Alistair Hinton has included parts for soprano, alto, baritone and contrabass saxophones in his Concerto for 22 Instruments completed in 2005.

In rock and jazz music

Since 2004, the rock group Violent Femmes have incorporated the contrabass saxophone into the band's live performances as well as their newest albums. Blaise Garza's contrabass saxophone often plays in unison with the bass guitar, and is featured heavily on their ninth studio album, We Can Do Anything.[8][9]

American multi-instrumentalist Anthony Braxton has used contrabass saxophone in jazz and improvised music.[10] He can be heard playing the instrument on the albums The Aggregate (1988), Dortmund (Quartet) 1976 (first released in 1991), and Four Compositions (GTM) 2000 (released 2003).

Performers

The contrabass saxophone has most frequently been used as a solo instrument by woodwind players in the genres of jazz and improvised music who are searching for an extreme or otherworldly tone. The difficulty of holding and controlling the instrument (let alone playing it) makes performing on the instrument a somewhat theatrical experience in and of itself. On older instruments, playing is difficult too; it takes an enormous amount of air to sound notes in the low register. Thanks to refinements in their acoustical designs and keywork, modern contrabass saxophones are no more difficult to play than most other saxophones.

An increasing number of performers and recording artists are making use of the instrument, including Anthony Braxton, Paul Cohen, David Brutti, Jay C. Easton, Randy Emerick, Blaise Garza, Marcel W. Helland, Robert J. Verdi, Joseph Donald Baker, Thomas K. J. Mejer, Douglas Pipher, Scott Robinson, Klaas Hekman, Daniel Gordon, Daniel Kientzy, and Todd A. White. It is also used by saxophone ensembles including the Raschèr Saxophone Orchestra, Saxophone Sinfonia, National Saxophone Choir of Great Britain, Zurich Saxophone Collective, Northstar Saxophone Quartet, Koelner Saxophone Mafia, Toronto-based Allsax4tet and the Nuclear Whales Saxophone Orchestra.[11]

References

- 1 2 Cohen, Paul M. (6 April 2015). "The Magnificent Contrabass Saxophone". The MET. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ↑ Kahlke, Helen (11 May 2012). "Eb Tubax". Bassic Sax. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ↑ "Contrabass Saxophone (E♭)". Munich, Germany: Benedikt Eppelsheim Wind Instruments. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ↑ "List of Available Saxophones". Milan: Romeo Orsi. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009.

- ↑ "Instruments made on request". Milan: Romeo Orsi. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009.

- ↑ "Traditional Low A Contrabass Saxophone". São Paulo, Brazil: J'Élle Stainer Extreme Saxophones. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ↑ Cottrell 2012, p. 276.

- ↑ Leslie, Jimmy (1 April 2016). "Brian Ritchie: Finding Balance with the Violent Femmes". Bass Player. New York: NewBay Media. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ↑ "Violent Femmes Announce New Album, Release First Single". Bass Magazine. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ↑ Cottrell 2012, p. 288–289; ill. 97.

- ↑ "Meet the Nuclear Whales Saxophone Orchestra!". Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

Bibliography

- Cottrell, Stephen (2012). The Saxophone. Yale Musical Instrument Series. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300100-41-9. LCCN 2012028346. OCLC 844030644. OL 25377233M. Wikidata Q113952716.

External links

- J’Élle Stainer

- Contrabass saxophone page from www.contrabass.com website

- Contrabass saxophone page from Jay C. Easton's web site

- Really Big Blues

- "Bahamut" by Hazmat Modine (click "Bahamut" to listen)

- MP3 excerpt of "Polpis Dreaming" by Carson P. Cooman, op. 410 (2002) for contrabass saxophone and piano, performed by Jay C. Easton

- Video of Marcel W. Helland playing a Contrabass Saxophone.