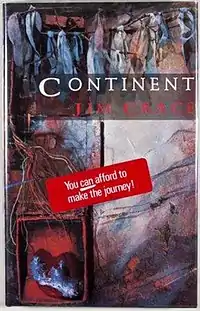

Continent, Jim Crace's first novel, was published in 1986 by Heinemann in the UK and Harper & Row in the US. It won the Whitbread First Novel of the Year Award, the David Higham Prize for Fiction, and the Guardian Fiction Prize.[1] The book consists of seven stories descriptive of life in an imaginary seventh continent. Translations have subsequently divided between providing a title incorporating that gloss, as in the Dutch[2] and Italian,[3] and keeping to the original, as in the Portuguese,[4] Spanish,[5] Czech[6] and Serbian.[7]

A patchwork novel

When Crace was first commissioned by Heinemann to write them a piece of fiction, his experience was more as an author of short stories and journalistic pieces. Therefore he created what was, in his words, "a patchwork of linked, shorter pieces…a patchwork of different colours but made up of the same material".[8] Most of the pieces had already had separate publication in The Fiction Magazine, New Review, The London Magazine, Quarto, London Review of Books and Encounter[9] prior to the novel's appearance. Later Crace was to describe his book as "a novel in stories about an invented continent struggling with the dislocations of progress".[10]

The stories are told by, or sometimes about, separate characters and from a variety of points of view. They include:

- "Talking Skull", which is related to fellow students by Lowdo, whose family money comes from a backward country district. There his father trades in the milk of hermaphrodite cows for its supposed aphrodisiac and fertility enhancing properties. The proceeds from this trade in superstition have paid for his university education and the young man must now reconcile his past with his prospects for the future. The title comes from an African folk tale[11] mentioned by Lowdo in which a skull's confession that "talking brought me here" brings about its discoverer's death.

- In "The world with one eye shut" an obscure lawyer's clerk tells how he is snatched from the street and imprisoned because of the affection his retarded sister conceives for a newly recruited soldier of an oppressive regime.

- "Cross-Country" features a VSO schoolteacher from Canada who attracts attention to himself by keeping up his jogging training in a remote mountain village. This arouses the jealousy of 'Isra-Kone, the local hero, because of the diminished attention he is now receiving. But when he challenges the teacher to a race against himself on horseback, the new-comer's self-discipline and strategy triumph.

- The narrator of "In Heat" is the eldest daughter of the now deceased Professor Zoea. She describes her father's investigation of a forest tribe whose women conceive at only one time of year and how he came away with a prepubescent native girl in order to study her physiological development. Late in life she finally deduces the truth about her own origin.

- The city scribe of "Sins and Virtues" is the last master of the sacred Siddilic script. Having sacrificed everything to perfect his art, he has retired in old age to live in frugal simplicity. When Americans arrive and start buying up old examples of his work, a government Minister visits him and suggests a profitable partnership. Reluctant to provide inauthentic fresh copies, the calligrapher finds a Syrian teashop owner who is trading in clumsy forgeries and buys up his stock with funds left by the Minister to bribe him, reasoning that no one will tell the difference.

- "Electricity" concerns a remote agricultural town in the Flat Centre that is to be supplied with electricity through the political connections of landowner Nepruolo. Awni, the local busybody, boastfully takes the credit and prepares his property for the moment the switch is turned on. But the celebration brings disaster to himself, while those who should have benefitted most become alienated and sceptical.

- "The Prospect from the Silver Hill" describes the predicament of a company agent responsible for testing ores brought to him at Ibela-Hoy, "the hill without a hat". Traces of ore or valuable earths that he sends back to headquarters are rejected, so that he can neither profit from his position nor escape. In his isolation, he is plagued with persistent insomnia and his sanity becomes unhinged. When at last silver is discovered and he foresees the desolation which exploitation will bring, he throws away the samples and climbs up above the snowline, fantasising there the family he has never had.

An allegorical location

One reviewer at least was sceptical of whether the book really could be called a novel. "In Crace's fables, things don't quite dovetail; since the prose is for the most part measured and vivid, the effect is often one of surreal displacement, an out-of-time distillation, free of cause and effect, of how societies get ruined and never rebuilt."[12] Yet, though there is no continuity of characters from story to story, there is continuity of continental commodities and locations: the extra hard but handsome tarbony wood, for example, or the four-winged bat-moth that is used locally for divination. The hieratic Siddilic language and its script also appear more than once, and there is mention of the Mu Coast where the wealthy have their resorts. What makes this seventh continent more convincing, in addition, is that it is not wholly imaginary. Crace has admitted that some parts in it were strongly inspired by Sudan and Botswana,[13] and other places outside Africa where he had worked in the past.

Another problem with the work seems to be assigning it to a genre. Crace admits to having been inspired by the approach of Magic realism when he started to write Continent but wanting to go beyond that to a closer criticism of social issues almost by stealth. "Imaginative fiction dislocates. What traditional writing does – what I do – is to dislocate the issues of the real world and place them elsewhere."[14] Because the places and societies in this continent are so vividly imagined, they serve as "an indirect, sometimes almost allegorical, reflection of reality that [Crace] achieves through dislocation".[15]

One of Crace's strategies in making his imaginary continent more real is to integrate it into the everyday world through frequent mention of visitors from the other continents or of those educated there away from home and then returning. Using the weapons of deliberate indirection and ambiguity of tone in this way allows the author, or his surrogate narrators, to satirise more convincingly what are standard villains anywhere: politicians hungry for power and profit; school teachers who use their position to spread a self-serving and conservative scepticism; the "mercantile instincts of supply and demand"[16] that are the target in "The Talking Skull" and "Sins and Virtues". Though subsequent novels may have been more orthodox in form, ambiguity of location continues to such a degree that commentators commonly describe his creations as taking place in 'Craceland'. The targets, however, do not change because human nature does not change.[17][18]

References

- ↑ Jim Crace Papers, Harry Ransom Center

- ↑ Het zevende werelddeel (1988)

- ↑ Settimo continente (1992)

- ↑ Continente (1988)

- ↑ Continente (1989)

- ↑ Kontinent (2003)

- ↑ Kontinent (2006)

- ↑ Introduction to the 2017 edition, p.ix

- ↑ Chris Morrow

- ↑ Adam Begley, Paris Review 179, 2003, "Jim Crace, The Art of Fiction"

- ↑ Bascom, William. "African Folktales in America: I. The Talking Skull Refuses to Talk", Research in African Literatures 8.2 (1977), pp. 266–291

- ↑ Kirkus Review

- ↑ "The Imaginary Landscapes of Jim Crace’s Continent", Petr Chalupský, p.202

- ↑ Adam Begley, "A Pilgrim in Craceland", Southwest Review 87.2/3 (2002)

- ↑ Chalupský p.201

- ↑ Chalupsky p.209

- ↑ Max Liu, "Jim Crace: 'My books dislocate the reader rather than locate them', Financial Times, 9 February 2018

- ↑ Philip Tew, Exploring Craceland (2006), Manchester scholarship online