Community banking is a non-traditional form of money-lending.[1] Unlike banks or other classic lending institutions, the funds that community banks lend to borrowers are gathered by the local community itself. This tends to mean that the individuals in a neighborhood or group have more control over who is receiving the capital and how that capital is being spent. This practice has existed in some form for centuries; in ancient Egypt, for example, when grain was often used as currency, local granaries would store and distribute the community’s food supply.[2] Since that time, a variety of community banking models have evolved.

Overview

Community banking is a form of empowerment-based economics which falls under the larger umbrella of micro-finance. Micro-finance as a whole is focused on the entrepreneurship of individuals, generally with a goal of lifting low-income or disadvantaged groups out of poverty and providing the means for them to prosper.[3] A very successful example of micro-finance can be seen in the Grameen Bank.

Although there are many different models of community banking, the goal is always located in the socio-economic growth of communities through the sharing of resources.[4] While this can include the participation of banks or other traditional money-lending institutions, this is not necessarily the case. The specific framework and practices of the community bank depend largely on its location in the world and the culture that has shaped it.

It is thus important to recognize the paramount power of the community in this process to make decisions and control the allocation of funds. Community banking is closely linked to tenets of both social work in general and community organizing in particular, wherein each person is regarded with dignity and seen as a force for change. It is generally initiated and organized by the collective rather than an outside institution (as is the case in more traditional models), and thus reflects the power of individuals in creating social change. However, the sovereignty of the community requires that as professionals enter, they do so from a place of cultural humility.[5] The philosophical foundation of community banking is that the collective knows best, and imposing the views of an outsider onto this system would dismantle the nature of the work.

Models by country

Community banking looks very different in individual settings or within unique groups.

United States

In the United States, community banks are a common institution. The US tends to follow a more traditional money-lending model in this way, but still incorporates collective ideals in that the community banks are locally owned. They remain specific to individual neighborhoods, and are thus more able to respond to community needs.[6]

India

In India, community banking looks very different. Self-Help Groups (SHG) are often instituted in which members of the local community join together and pool capital resources for the purpose of lending to members. Sometimes, the Self-Help Group is backed by a non-profit organization or even a government-backed bank, but this is not always the case. Self-Help Groups are small, with homogeneous membership, and high attendance rates. They value transparency in their practices and utilizing their savings for the purposes of lending. Because the borrowers are members of the SHG, they tend to experience lower interest rates, greater understanding should they have trouble repaying the loan, and greater flexibility overall. This model is closely linked to tenets of both social work in general and community organizing in particular, wherein each person is regarded with dignity and seen as a force for change. Community banking, in this model, is initiated and organized by the collective rather than an outside institution (as is the case in more traditional models), and thus reflects the power of individuals in creating social change.[7]

Nigeria

Another community banking model in Nigeria is the Credit Development Division. The need for a community banking model arose out of the desire to lessen the gap of credit accessibility in rural areas and to stimulate the economy. Employees in the Division are given the responsibility of planning and implementing credit programs to customers, coordinating alongside community members and other local bodies in order to distribute lines of credit and offering savings opportunities, develop credit tools focusing on security, down-payments, loan repayment periods, and interest and fees. A key component of this approach is that the target customers of the community banks were farmers. Ultimately the goal was to increase productivity and establish a better market for their products. In this model, the bank invests directly into a project without the use of a middle man or negotiator.[8]

Tanzania

The Tanzanian government in collaboration with SEDIT (Social and Economic Development Initiative of Tanzania) implemented a tool called Village Community Banks, or VICOBA. Development of this model included four key elements: group formation, governance, bank operations, and capacity building. Residents in several pre-selected villages voluntarily joined a group consisting of 30 members and then determined the rules and regulations of how the community bank would function. Once members completed the training sessions they could begin to take out loans predetermined projects. During the first few months members can take out short term loans and once they have developed entrepreneurship skills, they can take out longer term loans of up to six months. Lastly, SEDIT provided technical skills to participants over a period of fourteen to sixteen months. Training focused on the forming and regulating of a VICOBA group, how to create group guidelines and resolve conflicts, regulations on running savings and credit transactions in addition to entrepreneurial skills.[9]

Ecuador

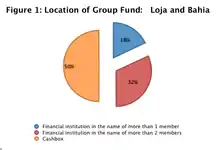

In 1999, Peace Corps Ecuador piloted the community banking program Programa de Ahorro y Crédito (PAC), which was adapted from a similar program in Niger called Mata Masu Dubara (Women Moving Ahead). A study of the program was conducted in 2010 from the nonprofit Freedom from Hunger, which evaluated two community banking programs in Ecuador. Participants in the banks were surveyed to determine the effectiveness of the local banking approach. Results showed the most common uses for loan funds were related to health care, investments in business and agricultural enterprises, as well as expenses for home improvements and school. The study found that half of community banks stored their money in a cashbox and nearly a third put the funds in a bank account in the name of one group member (See Fig. 1).[10]

Criticisms

Although community banking aims to empower and encourage economic development within communities, there is criticism that this is not always the case. In Indian models, for example, some argue that the lending process is encouraging households into much greater levels of debt than they can handle.[7] As a result, income insecurity is actually rising and class polarization increases.

Similar arguments are being made in Bangladesh, where women are bearing the brunt of the increased micro-financed debt. "Empowerment" is not as simple as providing monetary resources, as it fails to consider the many facets of life that community banking may have on individual families and cultures (for instance, how will the increase in capital change family dynamics, women's workload, etc.). To be truly effective, many argue that a more transformative model would have to take place in order to have a lasting impact on the daily lives of community members.[11]

Issues encountered in the Tanzanian community banks related to culture, infrastructure, and lack of available funds. Women were often unable to participate in the banks due to their husbands prohibiting them from becoming members; this was especially common in rural parts of the country. In some cases participants did not see the advantages of community banks as well as having misconceptions about the program. Some of the communities were located in remote areas that were difficult to reach by facilitators and agencies such as SEDIT. Lastly, inadequate funding limited participation because of the inability to collect sufficient start up funds.[9]

The Nigerian model was criticized as being ineffective because bank operators rarely gave out loans. A study of the community banks found that only 23.3% of deposits were given back to the community as loans.[8]

Based on the Freedom from Hunger study, several recommendations were made to Peace Corps Ecuador so as to make the community banking model more efficient. Many of these focused on creating a standard of how to start a community bank including providing training to participants on accounting and group facilitation skills. Another recommendation was to develop a training module to be given to youth so as to increase skills in financial responsibility and prioritizing.[12]

References

- ↑ Minsky, Hyman P. (March–April 1993). "Community development banks: An idea in search of substance". Challenge. 36 (2): 33–41. doi:10.1080/05775132.1993.11471653.

- ↑ Gascoigne, Bamber. "Historyworld". History of Banking. Retrieved March 1, 2014.

- ↑ Fisher, Thomas; M. S. Sriram (April 2004). "Organisation of micro-finance". Economic and Political Weekly. 39 (14): 1475–1476.

- ↑ Pitt, Mark M.; Shahidur R. Khandker; Jennifer Cartwright (July 2006). "Empowering women with micro finance: Evidence from Bangladesh". Economic Development and Cultural Change. 54 (4): 791–831. doi:10.1086/503580. JSTOR 503580. S2CID 153551287.

- ↑ Tervalon, Melanie; Jann Murray-Garcia (May 1998). "Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education". Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 9 (2): 117–125. doi:10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. PMID 10073197. S2CID 2440411.

- ↑ Hoenig, Thomas M. (2003). "Community banks and the dederal reserve". Economic Review. 88 (2).

- 1 2 Morgan, Jamie; Wendy Olsen (June 2011). "Aspiration problems for the Indian rural poor: Research on self-help groups and micro-finance" (PDF). Capital & Class. 35 (2): 189–212. doi:10.1177/0309816811402646. S2CID 42660774.

- 1 2 Onugu, Charles Uchenna (2000). "The Development Role of Community Banks in Rural Nigeria". Development in Practice. 10 (1): 102–107. doi:10.1080/09614520052574. PMID 12295957. S2CID 38292095.

- 1 2 Kihongo, Michael Renatus. "Impact assessment of Village Community Bank (VICOBA), a microfinance project : Ukonga Mazazini".

- ↑ Proaño, Fleischer; Laura, Megan Gash and Amelia Kuklewicz. (October 2010). "Strengths, Weaknesses and Evolution of the Peace Corps' 11-Year-Old Savings Group Program in Ecuador". Freedom from Hunger Research Report. 13: 37.

- ↑ Aslanbeiugui, Nahid; Guy Oakes and Nancy Uddin (April 2010). "Assessing Microcredit in Bangladesh: A Critique of the Concept of Empowerment". Review of Political Economy. 22 (2): 181–204. doi:10.1080/09538251003665446. S2CID 153709847.

- ↑ Proaño, Fleischer; Laura, Megan Gash and Amelia Kuklewicz (October 2010). "Strengths, Weaknesses and Evolution of the Peace Corps' 11-Year-Old Savings Group Program in Ecuador". Freedom from Hunger Research Report. 13: 37.