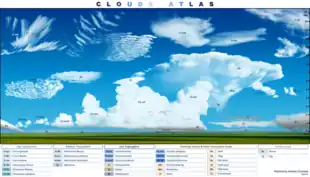

A cloud atlas is a pictorial key (or an atlas) to the nomenclature of clouds. Early cloud atlases were an important element in the training of meteorologists and in weather forecasting, and the author of a 1923 atlas stated that "increasing use of the air as a means of transportation will require and lead to a detailed knowledge of all the secrets of cloud building."[1]

History

Throughout the 19th century nomenclatures and classifications of cloud types were developed, followed late in the century by cloud atlases. The first nomenclature ("naming", also "numbering") of clouds in English, by Luke Howard, was published in 1802.[1] It followed a similar effort in French by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck in 1801. Howard's nomenclature defined four fundamental types of clouds: cirrus or thread-cloud, cumulus or heap-cloud, stratus or flat cloud (level sheet), and nimbus or rain-cloud (see List of cloud types). There followed a long period of development of the field of meteorology and the classification of clouds, leading up to 1896, the International Year of Clouds. The history of this period is the subject of a popular book, The Invention of Clouds.[2] During that time, the Englishmen Rev. Clement Ley and Hon. Ralph Abercromby, were influential. Both men died before the classification was settled, however. Ley wrote a book, Cloudland, that is well known to meteorologists. Abercromby contributed a number of papers on the subject, stressing the most important (and then novel) fact that clouds are the same everywhere in the world. He also wrote in collaboration with Hugo Hildebrand Hildebrandsson a detailed classification of clouds. This was adopted in Hildebrandsson's 1890 Cloud Atlas.

In 1891 the International Meteorological Conference at Munich recommended the classification of Abercromby and Hildebrandsson.

In 1896 another International Meteorological Conference was held, and in conjunction with it was published the first International Cloud Atlas. It was a political and technical triumph, and an immediate de facto standard. The scientific photography of clouds required several technical advances, including faster films (shorter exposures), color, and sufficient contrast between cloud and sky. It was Albert Riggenbach who worked out how to increase the contrast by using a Nicol prism to filter polarized light. Others learned to achieve similar results using mirrors or lake surfaces, and selectively photographing in certain parts of the sky.[3]

Many subsequent editions of International Cloud Atlas were published, including editions in 1906 and 1911. In this interval several other cloud atlases appeared, including M. J. Vincent's Atlas des Nuages (Vincent's Cloud Atlas) in 1908 in the Annales of the Royal Observatory, Brussels, Volume 20. It was based on the 1906 International Cloud Atlas, but with additions, and it classified the clouds into three group by height of the cloud base above ground: lower, middle, upper.[4]

Notable cloud atlases

The 1890 Cloud Atlas is the first known cloud atlas and book of this title, by Hildebrandsson, Wladimir Köppen, and Georg von Neumayer.[5] It was an expensive quarto book of chromolithographs reproducing 10 color oil paintings and 12 photographs for comparison, and was designed to explore the advantages and disadvantages of photography for the scientific illustration of cloud forms.[6] Its printing was limited but as a proof of concept it was a great success, leading directly to the International Cloud Atlas.

The first International Cloud Atlas was published in 1896.[7] This was prepared by Hildebrandsson, Riggenbach, and Leon Teisserenc de Bort, members of the Clouds Commission of the International Meteorological Committee. It consists of color plates of clouds, mostly photographs but some paintings, and text in French, English, and German. The plates were selected from among 300 of the best color photographs of clouds provided by members of the commission. The atlas has remained in print since then, in multiple editions.

See also

References

- 1 2 Alexander McAdie (1923). A cloud atlas. Rand, McNally & company. p. 57. page 3

- ↑ Richard Hamblyn (2002). The Invention of Clouds: How an Amateur Meteorologist Forged the Language of the Skies (reprint ed.). Macmillan. p. 292. ISBN 0-312-42001-3.

- ↑ Lockyer, Sir Norman (February 4, 1897). "The photographic observation of clouds". Nature. 55 (1423): 322–325. Bibcode:1897Natur..55R.322.. doi:10.1038/055322b0.

- ↑ James Glaishier (1908). "Vincent's Cloud Atlas". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. Royal Meteorological Society (Great Britain). 34 (148): 258. Bibcode:1908QJRMS..34..233M. doi:10.1002/qj.49703414803.

- ↑ H. H. Hildebrandsson; W. Köppen; G. Neumayer (1890). Cloud Atlas. Hamburg.

Wolken-Atlas. Atlas des nuages. Mohr Atlas. With explanatory letterpress in German, French, English and Swedish.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Katharine Anderson (2005). Predicting the weather: Victorians and the Science of Meteorology. University of Chicago Press. pp. 221, 331. ISBN 0-226-01968-3.

- ↑ The International Meteorological Committee (1896). International Cloud Atlas, published by order of the Committee by H. Hildebrandsson, A. Riggenbach, L. Teisserenc de Bort, members of the Clouds Commission (in French, English, and German). Gauthier-Villars. pp. 31, 14 sheets of colored maps.

External links

- WMO International Cloud Atlas 2017

- Cloud Atlas at Clouds-Online.com

- Cloud Atlas at Pennsylvania State University

- Houze'sCloud Atlas at University of Washington

- Online Cloud Atlas at University of Missouri-Columbia

- Cloudman's Mini Cloud Atlas: The 12 Basic Cloud Classifications

- Cloud Atlas For In-Flight Spotters