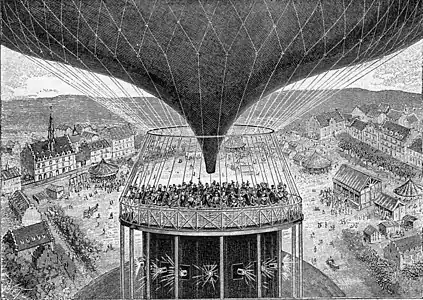

Cinéorama was an early film experiment and amusement ride presented for the first time at the 1900 Paris Exposition. It was invented by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson and it simulated a ride in a hot air balloon over Paris. It represented a union of the earlier technology of panoramic paintings and the recently invented technology of cinema. It worked by means of a circulatory screen that projects images helped by ten synchronized projectors.

Grimoin-Sanson began experimenting with movie cameras and projectors in 1895 and was in contact with other early researchers such as Étienne-Jules Marey. He patented the Cinéorama on 27 November 1897.

History

In 1893, kinetoscope from Thomas Edison had been causing an enormous speculation between the other inventors, engineers and philosophers about the future of theater and narration. This invention let a single spectator see an image moving through a little spy hole in the top part.

In the United States, Edison's new device was protected with patents and impeccable lawyers; but in other parts of the world he was not able to protect it. This way, loyal to the epoch's spirit, an electric engineer from England named Robert W. Paul was making his own fame with the reproduction of copies based on pirated designs.

Raoul Crimoin-Sanson, another French inventor, was on a trip to England. He was part of a small but growing group of cinema enthusiasts that had heard about the copy of the kinetoscope made by Paul, so they all decided to go after their own. When both their paths finally met, Sanson discovered that Robert Paul was not only making copies of kinetoscopes, but he was also working on a way to project them in a screen, a revolutionary idea which Sanson had also been thinking about.

Without hesitation, Raoul Crimoin-Sanson made an order. Many people had watched though that small spy hole to see an image moving, but only few had imagined it would ever be projected on a wall. Sanson and Paul had talked about it at length about where was the world of "image moving" or "motion picture" going, comparing notes with their ideas about a visual future. Paul was inspired by the science-fiction of movement (HG Wells). He imagined the public being surrounded by projected images to create a "moving image trip through time and space". Decades before the arrival of the cinematographic industry, Paul presented a patent for his idea. All kinds of tricks, constructions and projections of images were used so that the public could "feel a physical feeling" of movement through time and space. He was probably the first visionary of Virtual Reality. Robert Paul went on to invent the first commercial cinema projector in Great Britain, but his vision of a "moving image's journey through time" would never come to fruition.

The meeting with Paul should have been inspirational for Raoul Sanson as he returned to France with his own kinetoscope and immediately began to work on his own method to project images on a screen. Less than a year later, that was precisely achieved. A demonstration of his Phototachygraphe machine was made to journalists from all over France.

It was 1897 when the combination of two shots together in something similar to "a sequence" was not even a thoughtful reality, the film industry was decades away. The "moving image" or "motion picture" was not on anyone's radar, only a few bourgeois thinkers had paid attention. and yet, in France, Sanson was imagining an immersive and incredible future. The obtaining of motion pictures projected on a screen was just the first step in his real vision. The movie cameras were barely working, and he was already thinking about the combination: "If it is possible to project on a single screen, why is it not possible to project on multiple screens?". Within three years, the best investors, inventors, thinkers and entrepreneurs in the world would arrive to Paris for the magnificent "Universal Exhibition" in 1900. It was destined to mark the beginning of a century of technological progress.

Sanson had made a name for himself with the device "Photoachygraphe", and this way convinced some investors to support his idea. The Cinéorama was born. His idea consisted in the public being housed in a basket of a hot air balloon for a large-scale reproduction. Below the basket there was a projection room made to measure which housed 10 synchronized projectors arranged in a circle. Each one of them projected on a giant screen, resulting in an overwhelming 360-degree motion picture surrounded by a surprised audience.

However, there was a problem in the projection room. To make the machine work, the projection operator was put up in a narrow wooden box next to 10 huge and inefficient projection lamps. In just a few seconds of turning on the machine, the temperature in the projection room would raise hastily. Surprisingly, the projection operator achieved three days of projections with applause, but on the fourth day, he fainted because of the heat, causing concern to the authorities for the possibility of a fire.[1] This incident was a complete disaster for the company "Sanson's Cineorama".

A year later, the company was totally bankrupt and their material was sold on 1901.[2] Sanson left the cinema industry and got into the cork industry, falling into historical and cultural oblivion. Nevertheless, while his company died, the idea of immersive cinema had been born.[3]

Technical aspects

Cinéorama consisted of 10 synchronized 70 mm movie projectors, projecting onto 10 9x9 meter screens arranged in a full 360° circle around the viewing platform. The platform was a large balloon basket, capable of holding 200 viewers, with rigging, ballast, and the lower part of a huge gas bag.

The film to be shown was made by locking together 10 cameras with a single central drive, putting them in an actual balloon, and filming the flight as the balloon rose 400 metres above the Tuileries Gardens. On projecting the film, the experience was completed by showing the same film backwards, to simulate a descent. Some references describe a much longer experience, involving a trip to England, Spain, and the Sahara, but it is unclear whether the complete plan was realized.

Cinéorama lasted only three days at the Exposition. On the fourth day it was shut down by the police for safety reasons. Extreme heat from the projectors' arc lights, in the booth below the audience, had caused one workman to faint, and the authorities were worried about the possibility of a deadly fire. Cinéorama was never shown again, but a modern version, Circle-Vision 360°, was introduced at Disneyland in 1955 and continues in use today at other Disney properties.

Veracity disputed

A successful screening would have made Cinéorama one of the first, if not the very first, example of multi-screen film exhibition. But whether the staging of Cinéorama actually occurred has been called into serious doubt by French cinéma historian Jean-Jacques Meusy who summarises [translation from French]:

"Certainly Raoul Grimoin-Sanson had patented an apparatus consisting of ten shooting and projection devices and had built a pavilion in the Exposition to show the public the films he had made. But, contrary to what its inventor had claimed in his memoirs [published in 1926] there was no public performance since the technology of the day did not, it seems, allow the necessary synchronisation of ten projectors".[4]

Meusy contends that the drawings of Cinéorama that we see today derive instead from publicity and press speculation about what the screening could have looked like if it had taken place as planned.[5]

References

- ↑ "cinéorama, IDIS". proyectoidis.org. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ↑ "Who's Who of Victorian Cinema". www.victorian-cinema.net. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ↑ "The Epic Story Of Cinéorama, VR Cinema's Ancestor". VRROOM. 2016-09-09. Archived from the original on 2017-10-27. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ↑ Meusy, Jean-Jacques (2000-10-01). "La Polyvision, espoir oublié d'un cinéma nouveau". 1895. Mille Huit Cent Quatre-vingt-quinze (in French) (31): 153–211, paragraph 67. doi:10.4000/1895.68. ISSN 0769-0959.

- ↑ Meusy, Jean-Jacques (1991). "L'énigme du Cinéorama (The enigma of the Cinéorama)". Archives. 37: 1-16 [Online on Academia].

- MacGowan, Kenneth (Spring 1957). "The Wide Screen of Yesterday and Tomorrow". The Quarterly of Film Radio and Television. 11 (3): 217–241. doi:10.1525/fq.1957.11.3.04a00020.

- Comment, Bernard (1999). The Panorama. London: Reaktion Books. p. 76. ISBN 1-86189-042-7.

- Mannoni, Laurent. "Raoul Grimoin-Sanson". Who's Who of Victorian Cinema. Retrieved 2006-06-19.

- "The Panoramas of the Paris Exposition". Scientific American Supplement (1287): 20631. 1 September 1900.