Charles Sheeler | |

|---|---|

Charles Sheeler standing next to a window. c. 1910. | |

| Born | July 16, 1883 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Died | May 7, 1965 (aged 81) |

| Known for | Modern art, Photography |

| Movement | Precisionism, American Modernism |

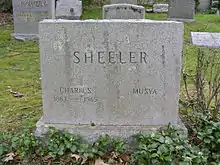

Charles Sheeler (July 16, 1883 – May 7, 1965) was an American artist known for his Precisionist paintings, commercial photography, and the avant-garde film, Manhatta, which he made in collaboration with Paul Strand. Sheeler is recognized as one of the early adopters of modernism in American art.

Early life and career

Charles Rettew Sheeler Jr. was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He attended the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art from 1900 to 1903, and then the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied under William Merritt Chase. He found early success as a painter and exhibited at the Macbeth Gallery in 1908.[1] Most of his education was in drawing and other applied arts. He went to Italy with other students, where he was intrigued by the Italian painters of the Middle Ages, such as Giotto and Piero della Francesca. After a trip to Paris in 1909, Sheeler was inspired by works of Cubist artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.[2] Returning to the United States, Sheeler felt that he would not be able to make a living as a modernist painter, so he took up commercial photography, focusing on architectural subjects. Sheeler was a self-taught photographer, learning his trade on a five dollar Brownie.

Early in his career, he was greatly impacted by the death of his close friend Morton Livingston Schamberg during the influenza epidemic of 1918.[3] Schamberg's painting had focused heavily on machinery and technology,[4] a theme that featured prominently in Sheeler's own work.

Sheeler owned a farmhouse in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, about 39 miles outside Philadelphia, which he shared with Schamberg until the latter's death. He was so fond of the home's 19th century stove that he called it his "companion" and made it a subject of his photographs. The farmhouse itself serves a prominent role in many of his photographs, which include shots of the bedroom, kitchen, and stairway. At one point he was quoted as calling it his "cloister." His work was also part of the painting event in the art competition at the 1932 Summer Olympics.[5]

On April 2, 1939, Sheeler married Musya Metas Sokolova, his second wife, six years after the death in 1933 of first wife Katharine Baird Shaffer (married April 7, 1921). In 1942, Sheeler joined the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a senior research fellow in photography, worked on a project in Connecticut with the photographer Edward Weston, and moved with Musya to Irvington-on-Hudson, some twenty miles north of New York. Sheeler worked for the Metropolitan Museum's Department of Publications from 1942 to 1945, photographing artworks and historical objects.[6]

Sheeler painted in a Precisionist style that complemented his photography and has been described as "quasi-photographic".[7]

Manhattan

In 1920, Sheeler invited photographer Paul Strand to collaborate on a "portrait" of Manhattan in film. The resulting 35mm nine-minute series of vignettes, called Manhatta after Walt Whitman's poem, Mannahatta, was the first avant-garde film created in America.[8]

Work with General Motors and Ford Motor Company

His work is featured at the General Motors Technical Center in Warren Michigan.[9] He was hired by the Ford Motor Company to photograph and make paintings of their factories.

Photography and film work

Films created by Charles Sheeler

- 1921 Manhatta (with Paul Strand)]

Photographic works

- 1917 Doylestown House: Stairs from Below (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- 1927 Criss-Crossed Conveyors, River Rouge Plant, Ford Motor Company (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

- 1928 Images from Vogue and Vanity Fair

Selected paintings

Early works

- Church Street El (1920) – The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland

- Still Life (1925) – M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco

- Lady of the Sixties (1925) – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Upper Deck (1928–1929) – Harvard Art Museum, Cambridge, MA

- American Landscape (1930) – Museum of Modern Art, New York City

- Americana (1931) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

- Classic Landscape (1931) – Barney A. Ebsworth collection

- View of New York (1931) – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Interior with Stove (1932) – National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- River Rouge Plant (1933) – Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City

- American Interior (1934) – Yale University Gallery, New Haven

- Ephrata (1934) – D'Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, MA

- City Interior (1936) – Worcester Art Museum, Worcester

Power series

In 1940, Fortune Magazine published a series of six paintings commissioned of Sheeler. To prepare for the series, Sheeler spent a year traveling and taking photographs. Fortune editors aimed to “reflect life through forms … [that] trace the firm pattern of the human mind,” and Sheeler chose six subjects to fulfill this theme: a water wheel (Primitive Power), a steam turbine (Steam Turbine), the railroad (Rolling Power), a hydroelectric turbine (Suspended Power), an airplane (Yankee Clipper) and a dam (Conversation: Sky and Earth) .

- Conversation: Sky and Earth (1939) – Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth

- Primitive Power (1939) – The Regis Collection, Minneapolis

- Rolling Power (1939) – Smith College, Northampton

- Steam Turbine (1939) – Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown

- Suspended Power (1939) – Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas

- Yankee Clipper (1939) – Rhode Island School of Design, Providence

Later works

- Interior (1940) – National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

- Fugue (1940) – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Bucks County Barn (1940) – Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago

- The Artist Looks at Nature (1943) – Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

- Water (1945) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- Incantation (1946) – Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn

- Amoskeag Canal (1948) – Currier Museum of Art, Manchester

- Windows (1952) – Hirschl & Adler Galleries, New York City

- Conversation Piece (1952) – Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem

- Aerial Gyrations (1953) – San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco

- New England Irrelevancies (1953) – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Ore Into Iron (1953) – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Stacks in Celebration (1954) – Dayton Art Institute, Dayton

- Architectural Cadences Number 4 (1954) – Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth

- Lunenburg (1954) – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Midwest (1954) – Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

- Golden Gate (1955) – Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

- Western Industrial (1955) – Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

- The Web (1955) – Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, NY

- On a Shaker Theme (1956) – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Red Against White (1957) – Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Composition Around White (1959) – Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein

Exhibitions

- "Charles Sheeler: Paintings, Drawings, Photographs" – Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 4 – November 1, 1939.[11]

- "Paintings by Charles Sheeler" – Dayton Art Institute, Dayton, Ohio, November 2 – December 2, 1944.[11]

- "Charles Sheeler: A Retrospective Exhibition" – Art Galleries, University of California at Los Angeles, October 11 – November 7, 1954. Toured November 18 – June 15, 1955 at the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, San Francisco; Fine Arts Gallery of San Diego; and Fort Worth Art Center, Fort Worth, Texas; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia; Munson-Williams Proctor Institute, Utica, New York.[11]

- "Charles Sheeler Retrospective Exhibition" – Allentown Art Museum, Allentown, Pennsylvania, November 17 – December 31, 1961.[11]

- "Charles Sheeler Retrospective Exhibition" - March 17 – April 14, 1963 - State University of Iowa, Department of Art.

- "Charles Sheeler" – National Collection of Fine Arts, Washington, DC, October 10 – November 24, 1968. Toured January 10 – April 27, 1969 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.[11]

- "Charles Sheeler: Across Media" – National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, May 7 – August 27, 2006. Toured at the Art Institute of Chicago, October 7, 2006 – January 7, 2007; and the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, February 10 – May 6, 2007. 50 works included, including paintings, photographs, works on paper, and a film.[12]

- "The Photography of Charles Sheeler" – Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Toured at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, June 3 – August 17, 2003; the Detroit Institute of Arts; and the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum. Nearly 100 works, including 90 photographs.[13]

- "Charles Sheeler: Fashion, Photography, and Sculptural Form", Curated by Kirsten M. Jensen, Ph.D., Gerry & Marguerite Lenfest, Chief Curator, James A. Michener Art Museum, March 18-July 9, 2017.

Gallery

Paintings

Dahlias and asters, 1912

Dahlias and asters, 1912 Chrysanthemums, 1912

Chrysanthemums, 1912 1913

1913 Lhasa,1916

Lhasa,1916 Barn, 1917. Conté crayon on paper

Barn, 1917. Conté crayon on paper Skyscrapers, 1922

Skyscrapers, 1922 Pertaining to Yachts and Yachting, 1922

Pertaining to Yachts and Yachting, 1922 Gladioli in White Pitcher, 1926

Gladioli in White Pitcher, 1926

Photographs

Side of White Barn, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 1915

Side of White Barn, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 1915 Bucks County Barn, 1914-1917

Bucks County Barn, 1914-1917 Portrait of Marcel Duchamp by Baroness Freytag-Lohringhoven, 1922

Portrait of Marcel Duchamp by Baroness Freytag-Lohringhoven, 1922 Criss-Crossed Conveyors, River Rouge Plant, Ford Motor Company, 1927

Criss-Crossed Conveyors, River Rouge Plant, Ford Motor Company, 1927 Bleeder Stacks, Ford Plant, Detroit, 1927

Bleeder Stacks, Ford Plant, Detroit, 1927 Ford Plant, River Rouge, Blast Furnace and Dust Catcher, 1927

Ford Plant, River Rouge, Blast Furnace and Dust Catcher, 1927

Notes

^ "Power: A portfolio by Charles Sheeler", Fortune magazine (December 1940) Time Inc., Volume XXII, Number 6

References

- ↑ Borland, Jennifer. Finding Aid to the Charles Sheeler Papers, circa 1840s-1966, bulk 1923-1965. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Murphy, Jessica (2000). ""Charles Sheeler (1883–1965)"". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Grace Glueck review of Morton Schamberg, NY Times, 1982 Retrieved August 11, 2010

- ↑ Pohald, Mark (October 2007). "Charles Sheeler: Across The Media". Exhibit Review. Chicago.Art Institute.

- ↑ "Charles Sheeler Jr". Olympedia. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ↑ Warren, Lynne, ed. (2006), Encyclopedia of twentieth-century photography, New York Routledge, p. 1418, ISBN 978-0-203-94338-0

- ↑ [Styles, schools and movements, published by Thames & Hudson 2002 Amy Dempsey]

- ↑ "Paul Strand, Charles Sheeler. Manhatta. 1921". moma.org. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ↑ "General Motors Technical Center". Society of Architectural Historians. 23 July 2018.

- ↑ Conroy, Sarah Booth (August 10, 1983). "GSA Finds Lost Sheeler Canvas". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roberts, Norma J., ed. (1988), The American Collections, Columbus Museum of Art, p. 198, ISBN 0-8109-1811-0.

- ↑ "NGA – Charles Sheeler: Across Media (5/2006)". National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on May 9, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ↑ "The Photography of Charles Sheeler". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

Further reading

- Brock, Charles (2006), Charles Sheeler: Across Media, Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, in association with University of California Press, Berkeley, ISBN 978-0-520-24872-4.

- Friedman, Martin (1975), Charles Sheeler, New York: Watson/Guptill Publications.

- Harnsberger, R. Scott (1992), Ten Precisionist Artists: Annotated Bibliographies, Westport: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-27664-4.

- Lucic, Karen (1991), Charles Sheeler and the Cult of the Machine, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-11111-0.

- Murphy, Jessica. “Charles Sheeler (1883–1965).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (November 2009)

- Rawlinson, Mark (2008), Charles Sheeler: Modernism, Precisionism and the Borders of Abstraction, London: IB Tauris, ISBN 978-1-85043-902-8.