Charles Forbes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Director of the Veterans Bureau | |

| In office August 9, 1921 – February 28, 1923 | |

| President | Warren Harding |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Frank Hines |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 14, 1878 Scotland, United Kingdom |

| Died | April 10, 1952 (aged 74) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Education | Cooper Union Columbia University Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1894–1900 (Marine Corps) 1900–1908, 1917–1918 (Army) |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 41st Infantry Division 33rd Infantry Division |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Awards | Croix de Guerre Army Distinguished Service Medal |

Charles Robert Forbes (February 14, 1878 – April 10, 1952) was a Scottish-American politician and military officer. Appointed the first director of the Veterans' Bureau by President Warren G. Harding on August 9, 1921, Forbes served until February 28, 1923. His tenure was characterized by corruption and scandal.

Early life

Forbes was born February 14, 1878, in Scotland. As a child, he and his parents emigrated to America and the family lived in New York and Boston. When Forbes was 16 years old, he joined the Marines as a musician, and was eventually stationed at the Washington Navy Yard. Trained as an engineer, Forbes attended Phillips Exeter Academy, Cooper Institute in New York, Columbia University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Two months after enlisting in the Army in 1900, he was charged with desertion but restored to duty without a trial. Forbes served in the Philippines after completing his enlistment and was honorably discharged from the Army in the rank of sergeant first class in 1908.[1][2]

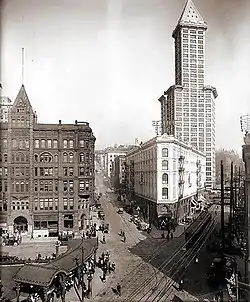

Pacific Northwest and Hawaii

After leaving the Army, Forbes engaged in construction work in the Pacific Northwest, moving to Seattle, where he became active in state politics. He married and had a daughter. In 1912, Forbes and his family moved to Hawaii, at that time a United States territory, and worked at the Pearl Harbor naval station as an engineer for the next five years. While in Hawaii, he served in four federal government appointments as Commissioner of Public Works, Chairman of the Public Service Commission, Chairman of the Harbor Commission and chairman of the Reclamation Commission, appointed by President Woodrow Wilson. While in Hawaii, Forbes became acquainted with vacationing senator Warren G. Harding, a meeting that would eventually change both of their lives. His charismatic personality and hospitality created a positive impression with Harding, and soon the two became close friends,[1][2] as did their wives.

World War I

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

After the American entry into World War I in April 1917, Forbes enlisted again in the army. He served overseas in France in the United States 41st and 33rd Infantry Divisions. He was awarded both the French Croix de Guerre (War Cross) and the Army Distinguished Service Medal, the citation for which reads:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Army Distinguished Service Medal to Lieutenant Colonel (Signal Corps) Charles R. Forbes, United States Army, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services to the Government of the United States, in a duty of great responsibility during World War I. As Division Signal Officer of the 33d Division, Lieutenant Colonel Forges performed his duties with marked distinction, maintaining communication at all times within the division, with adjoining units, and with the higher command. His ability and untiring devotion to duty were great factors in insuring the successes achieved by the Division.[3]

Forbes' final promotion was to the rank of colonel.[1] After the war, he returned to Washington State and worked for the Hurley-Mason construction company in Tacoma. Forbes later became the vice president in charge of the company's Spokane division.[4]

1920 Harding campaign

When his close friend Warren G. Harding was running for president in 1920, Forbes helped to deliver the state of Washington's delegate vote at the Republican National Convention held in Chicago.[1] Harding won the presidential election by promising a"return to normalcy" following the tumultuous war years.

War Risk and Veterans' Bureaus

Forbes sought desperately to be appointed chairman of the United States Shipping Board, an agency that controlled vast amounts of government shipping resources to private shippers. However, President Harding denied him the position and instead appointed Forbes to the War Risk Bureau on April 28, 1921.

On August 9, 1921, Harding signed an act of Congress consolidating the War Risk Bureau and several other agencies into the new Veterans' Bureau. Forbes was confirmed by the Senate after a hastily organized nomination and vote that same day. The bureau was created to aid the thousands of World War I veterans in need of medical and employment services. Each of the bureau's 14 nationwide offices had the authority to act without awaiting approval from the main office.[5]

Forbes' wife Katherine had direct access to the White House, having been given special privileges under Mrs. Harding's authority.

Veterans' Bureau tenure

(1920 postcard)

With a $500,000,000 (equivalent to $7,596,082,090 in 2021) annual budget at his disposal at the Veterans' Bureau,[1] Forbes hired 30,000 employees. The agency was overstaffed and many of the appointees sought means to justify their paid positions. During the short timespan during which Forbes led the bureau, he embezzled approximately $2 million, mainly in connection to the building of veterans' hospitals, the sale of hospital supplies intended for the bureau and kickbacks from contractors.[6]

Although 300,000 soldiers had been wounded in combat, Forbes had only allowed 47,000 claims for disability insurance, while many were denied compensation for reasons that Congress called "split hairs." Even fewer veterans received any vocational training under Forbes' direction of the bureau. While on the numerous trips (called "joy rides") that Forbes took to inspect hospital construction sites, he and his contractor friends allegedly indulged in parties and drinking. The men developed a secret code in order to communicate insider information and ensure government contracts.[7] According to congressional testimony, on an inspection trip to Chicago, Forbes gambled and accepted a $5,000 bribe from contractor J. W. Thompson and middleman E. H. Mortimer at the Drake Hotel to secure $17,000,000 in veterans' hospital construction contracts. Forbes claimed that the $5,000 payment was a loan. Mortimer also accused Forbes of conducting an affair with Mortimer's wife while on the inspection tours.[7] After Forbes returned from his inspection tours, he began to sell hospital supplies at severely discounted prices. He sold nearly $7,000,000 of much-needed hospital supplies for only $600,000.[8] Forbes was suspected of receiving kickbacks from contractors. When President Harding ordered Forbes to stop, Forbes disobeyed and continued to sell supplies.[9]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

On January 24, 1923, Forbes awarded Hurley-Mason Construction, his former company, a contract of $1,300,000 to construct a new veterans' hospital at American Lake, near Tacoma. By January 1923, rumors had spread indicating that Forbes would resign from the Veterans' Bureau in June.[4]

Resignation

When President Harding was informed in January 1923 that Forbes had refused to stop selling hospital supplies, Harding summoned Forbes to the White House and furiously demanded his resignation, allegedly grabbing Forbes by the throat while shouting, "You double-crossing bastard!"[11] Forbes pleaded with Harding to allow him to tender his resignation from outside the country, and Forbes resigned on February 15, 1923, while in Paris.[12] Among Forbes' final acts as chairman were numerous personnel changes at the bureau. In a searing attack on Forbes on the floor of the House of Representatives, Georgia congressman William Washington Larsen accused Forbes of making the personnel changes to reward his "henchmen" and remove those who may have had knowledge of Forbes' malfeasance.[13]

Congressional investigation

On March 2, 1923, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution to investigate the conduct of the Veterans' Bureau under Forbes. A three-member committee led by Pennsylvania senator David A. Reed[13] revealed that Forbes had left 200,000 unopened pieces of mail from veterans at the bureau. Among the testimony provided was that of E. H. Mortimer, to whom Forbes had delivered a $5,000 bribe while chairman of the Veterans' Bureau and whose wife was alleged to be romantically involved with Forbes.

On March 14, 1923, former Veterans' Bureau general counsel Charles F. Cramer committed suicide one week after resigning in the face of increasing scrutiny from Congress and the American Legion for his involvement in the scandal.[14]

In October 1923, Forbes divorced his wife Katherine, who had accused him of neglect and claimed that it had caused her to become ill.[15]

Trial, conviction, and prison sentence

Forbes was prosecuted and convicted of conspiracy to defraud the federal government, fined $10,000 and sentenced to a prison term of two years. He filed an appeal, but the United States Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago upheld the conviction.[1] On entering prison, Forbes said, "I don't suppose any prison is a pleasant place to go, but I shall try to make the best of it."[16]

Forbes was incarcerated on March 21, 1926, at the Leavenworth federal penitentiary and served 20 months. His cellmate was Frederick Cook, an explorer convicted of fraud who claimed to be the first man to have reached the North Pole.[1]

New York World article

After his release from prison and in an effort to exonerate President Harding, Forbes wrote a December 4, 1927, article for the New York World, that alleged Harding was "duped" by his appointees and cabinet, known as the Ohio Gang. He claimed to have once discovered Jess Smith, an aide to Harding's attorney general Harry Daugherty, collecting $70,000 in $1,000 bills scattered on a Justice Department office floor. Forbes claimed that Smith had told him that it was Daugherty's cash on the floor. Forbes also claimed that the narcotics were rampant at Atlanta and Leavenworth federal prisons while Daugherty was attorney general as a result of chronic understaffing. Forbes accused Harding's personal physician Charles E. Sawyer of being a "pernicious meddler." Forbes asserted that Harding had not profited in any way from the scandals during his administration and that Harding was "excessively loyal" with his friends to his own detriment. Forbes claimed that at a White House poker game, Harding said that he would remove a $1,000 fine imposed on prize fighter Jack Johnson, who had been released from Leavenworth in 1921.[17]

On December 16, 1927, Forbes testified before a grand jury in Kansas City regarding his statement in the article claiming that narcotics were easily obtained within Leavenworth. After Forbes' lengthy testimony before the grand jury, he said that he was sworn to secrecy and refused to offer a statement to the press.[18]

Illness and death

In October 1949, Forbes underwent a major operation. He died at the Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C., at the age of 74 on April 10, 1952, after a long illness. He was interred at Arlington National Cemetery. He was survived by his wife Katherine T. Forbes and a daughter, Marcia.[19]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Werner (1935), Privileged Characters, pp. 24, 193-195, 228

- 1 2 New York Times, Col. C. Forbes Dies; Led Veterans' Unit, April 12, 1952.

- ↑ "Valor awards for Charles R. Forbes".

- 1 2 "Hurley-Mason to Construct New Hospital". Spokane Daily Chronicle. January 25, 1923. p. 6.

- ↑ "Harding Abolishes War Risk Bureau". The New York Times. August 10, 1921. p. 5.

- ↑ Administration of Veterans' Affairs (excluding Health and Insurance), (2010); Dean (2004), Warren G Harding, pp. 140, 141

- 1 2 The Charleston Gazette (February 13, 1924), pp. 1, 9

- ↑ Administration of Veterans' Affairs (excluding Health and Insurance), (2010)

- ↑ Joplin News Herald (Saturday, March 20, 1926), p. 1; Time (Monday, April 21, 1952), Milestones; Administration of Veterans' Affairs (excluding Health and Insurance), (2010); Dean (2004), Warren G Harding, pp. 140, 141

- ↑ "Q&A with Rosemary Stevens". C-SPAN. January 8, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ↑ Goldman, Eric F. (July 30, 1972). "The Harding Affair". Tropic (Miami Herald Sunday magazine). p. 10.

- ↑ "Col. Forbes Resigns Veterans' Office Post". February 16, 1923. p. 4.

- 1 2 "Congressional Probe of Veterans' Bureau Approved by Senate". The Atlanta Constitution. March 23, 1923. pp. 1, 4.

- ↑ "Worried by Critics, Cramer Takes Life". The New York Times. March 15, 1923. p. 1.

- ↑ The Bee (Friday, October 26, 1923), p. 4.

- ↑ Veterans' Bureau Scandal, (2010); Administration of Veterans' Affairs (excluding Health and Insurance), (2010); Name Index to Inmate Case Files, U.S. Penitentiary, Leavenworth, Kansas, 1895 - 1931; Joplin Globe (Saturday Morning, January 31, 1925), pp. 1,2; Joplin News Herald (Saturday, March 20, 1926), p. 1.

- ↑ Chicago Daily Tribune (December 4, 1927), Harding Duped by 'Ohio Gang,' Says Forbes, pp. 1, 16

- ↑ The Atlanta Constitution (December 17, 1927), Prison Drug Plot Bared By Forbes, p. 5

- ↑ Time (Monday, April 21, 1952), Milestones; New York Times (April 12, 1952), Col. C. Forbes Dies; Led Veterans' Unit

Works cited

Books

- Dean, John Wesley (2004). Warren G. Harding. New York, New York: Times Books Henry Holt and Company, LCC. ISBN 0-8050-6956-9.

- Pusey, Merlo J. (1951). Charles Evans Hughes Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan.

- Werner, M. R. (1935). Privileged Characters. New York: R.M. McBride & Company. ISBN 0-405-05905-1. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

Newspapers

- "Col. C. Forbes Dies; Led Veterans' Unit". New York Times. New York, New York. April 12, 1952.

- "Parties, Joy-Rides Featured Tours of Forbes, Irwin Says". The Charleston Gazette. Charleston, West Virginia. February 13, 1924. pp. 1, 9.

- "Forbes Divorced by His Wife Who Charges Cruelty". The Bee. Danville, Virginia. October 26, 1923. p. 4.

- "Forbes Admitted to Penitentiary". Joplin News Herald. Joplin, Missouri. March 20, 1926.

- "Charles Forbes and St. Louis Contractor are Found Guilty of Government Fraud Charge". Joplin Globe. Joplin, Missouri. January 31, 1925. pp. 1, 2.

Magazines

- "Milestones, Apr. 21, 1952". Time. April 21, 1952. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

Online

- "Seven Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount - 1774 to Present". Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- "Administration of Veterans' Affairs (excluding Health and Insurance)". 2010. Archived from the original on July 20, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- "Veterans' Bureau Scandal". Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- "Name Index to Inmate Case Files, U.S. Penitentiary, Leavenworth, Kansas, 1895 - 1931". Archived from the original on December 8, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

External links

Media related to Charles R. Forbes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles R. Forbes at Wikimedia Commons