Chandra Khonnokyoong | |

|---|---|

Chandra Khonnokyoong | |

| Title | Khun Yay Maharatana Upasika |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1909 Nakhon Pathom, Thailand |

| Died | 10 September 2000 Bangkok, Thailand |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Mahānikāya, Dhammakaya tradition |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro, Thongsuk Samdaengpan |

| Based in | Wat Phra Dhammakaya, Pathum Thani, Thailand |

| Successor | Luang Por Dhammajayo |

Chandra Khonnokyoong (Thai: จันทร์ ขนนกยูง; RTGS: chan khonnokyung), 1909 – 10 September 2000) was a Thai Maechi (nun) who founded Wat Phra Dhammakaya. Religious studies scholar Rachelle Scott has described her as "the most influential female meditation teacher in Thailand".[1][2]: 503 Her own students call her Khun Yay Achan Mahā-ratana Upasika Chandra Khonnokyoong (Khun Yay Achan, for short), an honorific name meaning "grandmother-master-great-gem devotee".[3][note 1] Although illiterate, she was widely respected for her experience in meditation, which is rare for a maechi. She managed to attract many well-educated students, despite her rural background and illiteracy.[5] Some scholars have raised the example of Maechi Chandra to indicate that the position of women in Thai Buddhism may be more complex than was previously thought.[2][6]

Early life

Chandra was born in 1909 into a middle class farming family in Nakhon Pathom province, of Thailand.[7] Her father was called Ploy, and her mother was called Phan,[8]: 263 and she had eight siblings.[9] She was born in an area of the province which contained many long-established temples, which may have affected her devotion to Buddhism.[9] Like most Thai women in those days, she had no formal education.[note 2] In her childhood years, she helped both with farming and the household. One day, when her father was drunk, he had a fight with Chandra's mother. Trying to downplay her mother's insulting words to her father, Chandra made him angry. He cursed Chandra, saying that she would be deaf for five hundred lifetimes. Thai people in those days believed that a parent's words were sacred, and would normally be fulfilled. When her father died unexpectedly in 1921, Chandra still wanted to reconcile with him. She believed that reconciliation would help dissolve the effects of Karma and lift the curse.[2]: 71 [8]: 264 [10]: 34

In 1927, Chandra heard that a meditation master in Thonburi was able to use meditation to communicate with beings in the afterlife.[11] This was Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro. To accomplish her wish to reconcile with her father, Chandra left her family eight years later and travelled to Bangkok to find her way to Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen, where Luang Pu Sodh was located at that time.[2]: 507 [10]: 34 At first, Chandra lived with her aunt in Bangkok. Later on, to acquaint herself with Wat Paknam, Chandra decided to work as a servant. She applied to work in a household which was regularly visited by a teacher from Wat Paknam. This was the household of Liap Sikanchananand in Saphan Han, Bangkok, in which Achan Thongsuk Samdaengpan came regularly to teach. After a while, Achan Thongsuk started to teach Chandra in private and Chandra quickly made progress in Dhammakaya meditation. Students in the Dhammakaya tradition believe that she eventually attained the state in meditation called Dhammakaya and was able to contact her father in the afterlife.[2]: 72 [10][11]

Wat Phra Dhammakaya often emphasizes Maechi Chandra's illiteracy, to make the point that she became a spiritual leader solely because of her character and spiritual maturity, rather than academic knowledge.[2]: 75 [12] The temple's biography states that "she made a classroom of the vast paddy fields of her youth".[13]: 14

Life at Wat Paknam

In 1938, with the permission of the mistress of the house, Chandra was taken by Achan Thongsuk to meet Luang Pu Sodh for the first time. She was going to spend a month at Wat Paknam. When she met Luang Pu Sodh, he addressed her with the words: "You are too late!" as though they had known each other previously.[2][11][12] He allowed her to join an experienced group of meditation practitioners in Wat Paknam without having to pass any probation or tests. This was highly unusual.[1][2][11] This privilege was not taken for granted by others at the temple, however, and she was looked down on at first. Despite these obstacles, she was able to develop her meditation and, still within the first month, was given a special meditation seat (เตียงขาดรู้) used for training mindfulness, considered a sign of inner progress.[13]: 40–4 Before her period of leave was finished, Chandra decided to ordain as a maechi and stay at Wat Paknam. She and Achan Thongsuk ordained on the same day.[2][11] In the literature of Wat Phra Dhammakaya, it is said that Maechi Chandra quickly became one of Luang Pu Sodh's best students and was praised by him as "first among many, second to none".[2]: 72–4 [11] At that time, she became well-known because people believed she had the ability to share merit with people who had died, analyze people's karma, and other forms of abhiñña (mental powers) coming from her meditation practice.[2]: 72–4 Maechi Chandra is believed by some practitioners to have prevented several bombs from hitting Bangkok during World War II.[1]

Luang Pu Sodh would often assign Maechi Chandra to teach different groups in different provinces. Because of her lack of formal education, at times she felt uncomfortable about this. Eventually, she managed to do this well.[11] She became known for being able to explain difficult teachings.[12] She emphasized self-discipline and practicing virtues such as respect and patience.[8]: 273–80 Though Maechi Chandra would travel and help to teach Dhammakaya meditation at times, most of her time was spent on meditating. Maechi Thongsuk had a much busier teaching schedule. After Luang Pu Sodh's death in 1959, Maechi Thongsuk got cervical cancer. Maechi Chandra took care of her in her last months, and organized a suitable funeral for her.[13]: 67–9

Setting up a new meditation centre

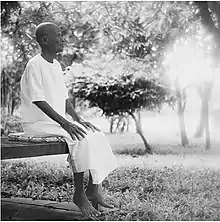

_with_a_temple_employee.jpg.webp)

After Luang Pu Sodh died in 1959, Maechi Chandra transmitted the Dhammakaya tradition to a new generation at Wat Paknam Bhasicharoen.[14] The house in which Maechi Chandra lived quickly became too small to accommodate all her students, and funds were raised to build a new house, called the "Dhammaprasit House" (บ้านธรรมประสิทธิ์).[13]: 80 Maechi Chandra encouraged meditation practitioners who were still students to ordain after graduation. One of the first of these was Luang Por Dhammajayo, who met Maechi Chandra when she was 54, and who ordained later in 1969 or 1970.[2]: 73 [9] The number of students increased quickly, and in 1975 exceeded the capacity of Wat Paknam. Continuing there became inappropriate. Plans were made for establishing a new meditation centre. An 80 acres (320,000 m2) plot of paddy-field was donated for building the centre by Khunying Prayat Suntharawet, a land owner of royal blood.[11] Having only 3,200 Baht ($80) to their name,[13]: 101–4 a group of meditation practitioners headed by Maechi Chandra began establishing the temple. On the new land a meditation center was gradually built. It was first officially established on Magha Puja Day, 20 February 1970, and called "Sun Phutthachak Patipattham" (ศูนย์พุทธจักรปฏิบัติธรรม; 'the Dhamma practice center of the Buddha-sphere'). Luang Por Dhammajayo and Maechi Chandra took responsibility for the finances of the establishment, and a lay-supporter, who later ordained as Luang Por Dattajivo, took responsibility for building on the site. Every canal in the temple compound was dredged and excavated by the volunteers and the trees in the temple were planted by hand. Villagers from the area became familiar with Maech Chandra and started to help her. In the beginning, the soil was very acidic.[13]: 108 [9]

While working to plant the trees, Maechi Chandra became seriously under-nourished and at one time came dangerously close to death. She recovered under medical attention.[13]: 157 In 1978, the meditation center became an official temple, and eventually was named "Wat Phra Dhammakaya".[15][16]: 656 Despite the initial difficulties, in the 1980s and 1990s the temple grew to be the largest in Thailand.[16]

During the period of establishment, Maechi Chandra sought finance to support the center and set the regulations for those living in the temple. Luang Pu Sodh was her model in this. An example of such a regulation was that a monk had to receive guests in public rooms rather than in their living quarters.[13]: 117–8 Asian Studies scholar Jesada Buaban believes that Maechi Chandra made Wat Phra Dhammakaya attractive, because most other Thai temples are male-led, with no women in a leading role.[17] Spokespeople of the temple describe the role of Maechi Chandra in the early period of the temple as a 'chief commander' (Thai: jomthap), whereas Luang Por Dhammajayo is depicted as a 'chief of staff' (Thai: senathikan) developing proper plans, and Luang Por Dattajivo is described as the practical manager.[18] During the years to follow, Maechi Chandra's role would gradually become less, as she grew older and withdrew more to the background of the temple's organization.[11]: 41–3

Death and heritage

In her old age Maechi Chandra was still active in the temple, though she had to be hospitalized from 1996 to 1997.[13]: 153–6 She died peacefully on 10 September 2000 at Kasemrat Hospital, Bangkok, at the age of ninety-one.[19] Her cremation was postponed for over a year in order to give time to everyone to pay their respects to her and make merit on her behalf.[2]: 507 Memorial chanting was held every day during this period.[9] When her funeral was held, on 3 February 2002, it was claimed that over 250,000 monks from thirty thousand temples throughout Thailand attended to show their final respects, which is unusual, even more so for a female renunciant in Thailand.[2]: 507 The heads of the monastic communities of several countries came to join.[2][7][20] Maechi Chandra's remains were burnt in a grand ceremony, using glass to ignite the fire by sun light. Her ashes were kept in a small stupa.[21][22]

In 2003, Wat Phra Dhammakaya built a monument in honor of Maechi Chandra, called the "Mahavihara Khun Yai Achan Mahā-ratana Upāsika Chandra Khonnokyoong". This is a hexagonal building with a meditation hall and a life-size golden image of Maechi Chandra in it,[2][3][13]: 201 which was cast earlier in 1998.[23] The temple has also named two other buildings after her. Also, the temple still organizes regular commemorations of Maechi Chandra, and the day of her cremation is commemorated in a "Day of the Honorable Teachers" (Thai: Wan Maha Puchaniyachan).[9]

Bibliography and works

- Dhammakaya Foundation (2005). Second to None: The Biography of Khun Yay Maharatana Upasika Chandra Khon-nok-yoong, Bangkok: Dhammakaya Foundation. ISBN 978-974-92746-6-8

- Surin Chaturapit, transl. (2012). Khun Yai's Teachings: Wisdom From an Enlightened Mind, Bangkok: Dhammakaya Foundation

Notes

- ↑ To refer to a maechi as "Khun", combined with an honorary kin term, is a common way of addressing a maechi on familiar, yet deferential terms.[4]

- ↑ This was because of traditional attitudes about a woman's role in society, but according to Lovichakorntikul et al. it was also related to the fact that schools were run by male monastics.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 Scott, Rachelle M. (2016). "Contemporary Thai Buddhism". In Jerryson, Michael (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-19-936238-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Scott, Rachelle M. (2010). "Buddhism, miraculous powers, and gender: Rethinking the stories of Theravāda nuns". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 33 (1–2).

- 1 2 Seeger, Martin (September 2009). "The Changing Roles of Thai Buddhist Women: Obscuring Identities and Increasing Charisma". Religion Compass. 3 (5): 811. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2009.00165.x.

- ↑ Cook, Nerida M. (1981). The position of nuns in Thai Buddhism: The parameters of religious recognition (Ph.D. Thesis). Research School of Archaeology and Anthropology, Australian National University. p. 153. hdl:1885/10414.

- ↑ Gombrich, R. (1996). "Freedom and Authority in Buddhism". In Gates, B. (ed.). Freedom and Authority in Religions and Religious Education. London: Cassell. p. 11.

- ↑ McDaniel, J (2006). "Buddhism in Thailand: Negotiating the Modern Age". Buddhism In World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 101–28. ISBN 1-85109-787-2.

- 1 2 Nemsiri, Mutukumara (1 February 2002). "Upasika Khun Yai the founder of Dhammakaya". Daily News (Sri Lanka). Lake House. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Lovichakorntikul, Petcharat; Putthithanasombat, Phramaha Min; Walsh, John (2017). "The virtuous life of a Thai Buddhist nun". In Kassam, Zayn R. (ed.). Women and Asian Religions. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-08275-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Tam ha... aphinihan Khun Yai Chan: Thammakai cha lom mai" ตามหา..อภินิหาร 'คุณยายจันทร์' ธรรมกายจะล่มมั้ย? [In Search for Khun Yai Chandra's Miracles: Will Dhammakaya survive?]. Kom Chad Luek (in Thai). 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 Mackenzie, Rory (2007). New Buddhist Movements in Thailand: Towards an Understanding of Wat Phra Dhammakaya and Santi Asoke. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-13262-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Fuengfusakul, Apinya (1998). ศาสนาทัศน์ของชุมชนเมืองสมัยใหม่: ศึกษากรณีวัดพระธรรมกาย [Religious Propensity of Urban Communities: A Case Study of Phra Dhammakaya Temple] (Ph.D. thesis). Buddhist Studies Center, Chulalongkorn University.

- 1 2 3 Falk, Monica Lindberg (2007). Making fields of merit: Buddhist female ascetics and gendered orders in Thailand. Copenhagen: NIAS Press. ISBN 978-87-7694-019-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Dhammakaya Foundation (2005). Second to None: The Biography of Khun Yay Maharatana Upasika Chandra Khonnokyoong. Bangkok: Dhammakaya Foundation.

- ↑ Heikkilä-Horn, M-J (1996). "Two Paths to Revivalism in Thai Buddhism: The Dhammakaya and Santi Asoke Movements". Temenos (32): 93–111.

- ↑ จาก "บ้านธรรมประสิทธิ์" สู่ "มหาธรรมกายเจดีย์" [From Ban Thammaprasit to the Maha Dhammakaya Cetiya]. The Dhammakaya Epic. Episode 3 (in Thai). 29 May 2016. Event occurs at 1:52. Channel 8 (Thailand). Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- 1 2 Swearer, Donald K. (1991). "Fundamentalistic Movements in Theravada Buddhism". In Marty, M.E.; Appleby, R.S. (eds.). Fundamentalisms Observed. The Fundamentalism Project. Vol. 1. Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50878-8.

- ↑ Buaban, Jesada (August 2016). ความทรงจำในดวงแก้ว: ความทรงจำที่แปรเปลี่ยนไปเกี่ยวกับวัดพระธรรมกายภายใต้ปริมณฑลรัฐบาลทหารปี พ.ศ. 2557–2559 [Memory in Crystal: Changing Memory on Dhammakaya Movement under the Umbrella of Military Junta 2014–2016] (pdf). The science of remembering and the art of forgetting 2nd conference (in Thai). Prince of Songkla University, Songkhla: Southeast Asian Studies Program, Walailak University. p. 2 n.3.

- ↑ "Thattachiwo hai pai nai" 'ทัตตชีโว'หายไปไหน? [Where is Dattajīvo?]. Kom Chad Luek (in Thai). 7 June 2016. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017.

- ↑ Litalien, Manuel (January 2010). Développement social et régime providentiel en thaïlande: La philanthropie religieuse en tant que nouveau capital démocratique [Social development and a providential regime in Thailand: Religious philanthropy as a new form of democratic capital] (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in French). Université du Québec à Montréal. pp. 130–1. Published as a monograph in 2016

- ↑ Rajakaruna, J. (28 February 2008). "Maha Dhammakaya Cetiya where millions congregate seeking inner peace". Daily News: Sri Lanka's National Newspaper.

- ↑ Somsin, Benjawan (4 February 2002). "200,000 [people say] farewell [to] sect founder". The Nation (Thailand). p. 1. Retrieved 5 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

- ↑ ลูกศิษย์คุณยายจันทร์รวมจิตเป็นหนึ่ง ทำบุญ 3 หมืนวัด [Students of Khun Yay Chandra make merit for 30,000 temples in unity]. Dokbia Thurakit (in Thai). 28 January 2002. p. 1. Retrieved 5 December 2016 – via Matichon E-library.

- ↑ "คุณยาย" ปัด "ระเบิด" ไม่พ้น [Khun Yay was not able to bounce off all bombs]. Kom Chad Luek (in Thai). 1 December 2018. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019.