| Rules for medieval miniatures | |

|---|---|

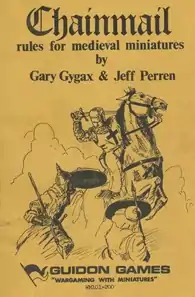

Cover for the first edition of Chainmail (1971) | |

| Designers | Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren |

| Illustrators | Don Lowry |

| Publishers | Guidon Games TSR, Inc. |

| Years active | 1971–1985 |

| Players | 2–10 |

| Playing time | 6 hours |

| Skills | Strategy, tactics |

Chainmail is a medieval miniature wargame created by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren. Gygax developed the core medieval system of the game by expanding on rules authored by his fellow Lake Geneva Tactical Studies Association (LGTSA) member Jeff Perren, a hobby-shop owner with whom he had become friendly. Guidon Games released the first edition of Chainmail in 1971.

Early history

Origins

In 1967, Henry Bodenstedt created the medieval wargame Siege of Bodenburg, which was designed for use with 40mm miniatures.[1] Gary Gygax first encountered Siege of Bodenburg at Gen Con I (1968), and played the game during that convention.[2] The rules for Siege of Bodenburg had been published in Strategy & Tactics magazine, and Jeff Perren developed his own medieval rules based on those and shared them with Gary Gygax.[1]

The original set of medieval miniatures rules by Jeff Perren were just four pages.[3] Gygax edited and expanded these rules, which were published as "Geneva Medieval Miniatures", in Panzerfaust magazine (April 1970), using 1:20 figure scale.[3] The rules were again revised, and then self-published in the newsletter of the Castle & Crusade Society, The Domesday Book, as the "LGTSA Miniatures Rules", in issue #5 (July 1970), using 1:10 figure scale.[3] Later issues of The Domesday Book introduce a rule system for man-to-man combat at 1:1 figure scale and a rule system for jousting.[4]

1st edition

Gary Gygax met Don Lowry at Gen Con III (1970), and Gygax later signed with Lowry when he founded Guidon Games to produce a series of rules called "Wargaming with Miniatures".[3] The first game published was a further expansion of the medieval rules, published as Chainmail.[3] Guidon Games released the first edition of Chainmail in 1971 as its first miniature wargame and one of its three debut products.[5]

Along with the previous medieval rules, Chainmail included a 14-page "fantasy supplement" including figures such as heroes, superheroes, and wizards.[3] The fantasy supplement also included mythical creatures such as elves, orcs, and dragons.[4][6] The fantasy supplement also referenced the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, Robert E. Howard, Poul Anderson, and Michael Moorcock.[7] The fantasy supplement encouraged players to refight fixed battles based on fantasy fiction by J. R. R. Tolkien, Robert E. Howard, and other writers.[8]

The Chainmail cover art of a fighting crusader was inspired by a Jack Coggins illustration from his book The Fighting Man: An Illustrated History of the World's Greatest Fighting Forces.[2] Both Perrin and Gygax "swiped" Coggin's artwork to illustrate their preliminary articles about Chainmail that appeared in Panzerfaust and The Domesday Book.[2] When Don Lowry of Guidon Games agreed to publish Chainmail, Lowry swiped the same Coggins illustration for the cover.[2] For the fantasy supplement, the illustration of a mounted knight charging towards a dragon, was drawn by Don Lowry, based heavily on an illustration by Pauline Baynes for J. R. R. Tolkien's Farmer Giles of Ham (1949).[2]

First edition Chainmail saw print in March 1971. It quickly became Guidon Games' biggest hit, selling one hundred copies per month.[9]

2nd edition

Guidon Games published Chainmail second edition in 1972.[10]

3rd edition

TSR eventually bought the rights to some of the back catalog of Guidon Games. Starting in 1975, they published Chainmail as their own product.[11] It went through eight different printings from 1975 to 1985.

Rule systems

Mass combat

A set of mass-combat rules, heavily indebted to the medieval systems of Tony Bath and intended for a 1:20 figure scale. These developed from the Lake Geneva medieval system originally published in Panzerfaust and in Domesday Book #5. In these rules, each figure represents twenty men.[1] Troops are divided into six basic types: light foot, heavy foot, armored foot, light horse, medium horse, and heavy horse.[1] Melee is resolved by rolling six-sided dice: for example, when heavy horse is attacking light foot, the attacker is allowed to roll four dice per figure, with each five or six denoting a kill.[12] On the other hand, when light foot is attacking heavy horse, the attacker is allowed only one die per four figures, with a six denoting a kill. Additional rules govern missile and artillery fire, movement and terrain, charging, fatigue, morale, and the taking of prisoners.[12]

Man-to-man combat

A set of man-to-man combat rules (for 1:1 figure scale), ultimately deriving from a contribution to Domesday Book #7. Gygax lost the name of the contributor, and thus the rules were published anonymously. The core of these rules became the Appendix B chart mapping various weapon types to armor levels, and providing the needed to-hit rolls for a melee round. The man-to-man melee uses two six-sided dice (2d6) to determine whether a kill is made.

Jousting

A set of jousting rules, which derive from the Castle & Crusade Society jousting rules published in Domesday Book #6, and reprinted in Domesday Book #13. These rules were originally designed for postal play; members of the C&CS could participate in jousting tourneys in order to raise their standing in the Society. Dungeons & Dragons refers to jousting matches utilizing the Chainmail rules.

Fantasy supplement

The core of these rules is the Appendix E chart showing the die rolls needed for various fantastic types to defeat one another in battle.

The first edition Chainmail fantasy supplement added such concepts as elementals, magic swords, and several spells including "Fireball" and "Lightning Bolt".[1] Borrowing a concept from Tony Bath, some figure types may make saving throws to resist spell effects; a stronger wizard can cancel the spell of a weaker wizard by rolling a seven or higher with two six-sided dice. Creatures were divided between Law and Chaos, drawing on the alignment philosophies of Poul Anderson, as popularized by Michael Moorcock's Elric series.[1] When fighting mundane units, each of the fantasy creatures is treated as one of the six basic troop types. For example, hobbits are treated as light foot and elves are treated as heavy foot.[1] Heroes are treated as four heavy footmen,[1] and require four simultaneous hits to kill; Super-Heroes are twice as powerful.

Use with Dungeons & Dragons

In the June 1978 issue of The Dragon, Gary Gygax wrote that for the first two years of Dungeons & Dragons, players played primarily without the use of any miniature figures. If visual aids were needed, then the players would draw pictures, or use dice or tokens as placeholders. By 1976, there was a movement among players to add the use of miniatures to represent individual player characters.[13]

In 1976, Swords & Spells was added as a rules supplement for Dungeons & Dragons, to provide fantasy mass combat rules for the game at 1:10 and 1:1 scale. In the foreword, Tim Kask describes Swords & Spells as the "grandson" of Chainmail.[14] In the introduction to the game, Gary Gygax wrote that the Chainmail fantasy supplement assumed man-to-man combat, and rules for "large-scale" fantasy battles were missing, so Swords & Spells was developed to cover 1:10 and 1:1 ratio fantasy battles:[15]

The FANTASY SUPPLEMENT written for CHAINMAIL assumed a basic man-for-man situation. While it is fine for such actions, it soon became obvious that something for large-scale battles was needed.

Reviews

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tresca, Michael J. (2010), The Evolution of Fantasy Role-Playing Games, McFarland, pp. 60–61, ISBN 978-0786458950

- 1 2 3 4 5 Witwer, Michael; Newman, Kyle; Peterson, Jon; Witwer, Sam (2018). Dungeons & Dragons Art & Arcana: A Visual History. Ten Speed Press. pp. 10–15. ISBN 978-0-399-58094-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shannon Appelcline (2014). Designers & Dragons: The '70s. Silver Spring, Maryland: Evil Hat Productions, LLC. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1-61317-075-5.

- 1 2 Harrigan, Pat; Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. (2016). "A Game Out of All Proportions". Zones of Control: Perspectives on Wargaming. MIT Press. OCLC 936684796.

- ↑ La Farge, Paul (September 2006). "Destroy All Monsters". The Believer Magazine. Archived from the original on 2008-09-20. Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- ↑ Mizer, Nicholas J. (22 November 2019). Tabletop role-playing games and the experience of imagined worlds. Cham, Switzerland. p. 30. ISBN 978-3-030-29127-3. OCLC 1129162802.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Pötzsch, Holger; Hammond, Philip, eds. (2019). War Games: Memory, Militarism and the Subject of Play. New York, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 182–183. ISBN 978-1-5013-5115-0.

- ↑ Peterson, Jon (2020). The Elusive Shift: How Role-Playing Games Forged Their Identity. MIT Press. pp. 19, 115. ISBN 978-0-2620-4464-6.

- ↑ Kushner, David (2008-03-10). "Dungeon Master: The Life and Legacy of Gary Gygax". Wired.com. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ↑ Harrigan, Pat; Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. (2016). Zones of Control: Perspectives on Wargaming. MIT Press. p. 762.

- ↑ Witwer, Michael; Newman, Kyle; Peterson, Jon; Witwer, Sam (2018). Dungeons & Dragons Art & Arcana: A Visual History. Ten Speed Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-399-58094-9.

- 1 2 "Chainmail" (PDF). americanroads.us. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ↑ Gygax, Gary (July 1978). "D&D Ground and Spell Area Scale". Dragon Magazine. No. 15. TSR Periodicals.

- ↑ Ewalt, David M. (2013). Of Dice and Men: The Story of Dungeons & Dragons and the People Who Play It. Scribner. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-4516-4052-6.

- ↑ Gygax, Gary (1976). Kask, Tim (ed.). Swords & Spells: Rules for Large-scale Miniatures Battles Based on the Game Dungeons & Dragons. Lake Geneva, Wisconsin: TSR Games. p. 1. OCLC 7541099.

- ↑ "The Playboy winner's guide to board games". 1979.