A Carnot wall is a type of loop-holed wall built in the ditch of a fort or redoubt. It takes its name from the French mathematician, politician, and military engineer Lazare Carnot. Such walls were introduced into the design of fortifications from the early nineteenth century. As conceived by Carnot, they formed part of an innovative but controversial system of fortification intended to defend against artillery and infantry attack.[1] Carnot walls were employed, together with other elements of Carnot's system, in continental Europe in the years after the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, especially by the Prussians, other Germans and Austrians.[1][2][3] Their adoption was initially resisted by the French themselves and by the British.[4][5]

Lazare Carnot and his system of fortification

Carnot was born in 1753. He became a military engineer at the age of 20. He became a politician during the French Revolution in 1789. He was responsible for the organization of the campaigns of the French Revolutionary Army, and later served under Napoleon. Carnot's "A treatise on the defence of fortified places" was published in 1810 with an English translation by Baron de Montalembert published in 1814.[6]

In this period the design of fortifications was based on the bastion "trace" or ground-plan. This had originated in Italy in the 16th century.[7] From the late 17th century the model system of fortification was considered to be that based on the bastion trace of Vauban, Louis XIV's military engineer.[8]

Carnot opposed the Bastion system.[9] The elements of his system were:

- vertical fire from mortars;

- a countersloping glacis;[10]

- sorties by defenders;[11]

- the "Carnot" wall and;

- separation of defence and attack.[1][12]

A conventional fort would have ramparts on which the cannon were mounted. The ramparts were surrounded by a ditch with vertical, or near vertical, sides, called the scarp (inner wall) and counterscarp (outer wall). The outer side of the ditch would have a glacis, a gently outwardly sloping earth bank at a slightly lower level than the ramparts. The glacis would be topped by a parapet with a flat area called the "covered way" (because it was "covered" by fire from defenders on the ramparts). This arrangement was intended to make it difficult for attackers to approach the fort while allowing defenders to observe, and fire on, approaching besiegers at some distance from the fort.[13]

As against this method Carnot's system did away with the covered way and steep counterscarp and made the glacis slope back into the ditch. (This is referred to as a countersloping glacis).[10] He placed a loop-holed wall in the ditch of the fortification. This had a chemin des rondes, or sentry path, to the rear allowing defenders to move along behind the wall. As well as firing at attackers the defenders were able to make sorties from behind the wall up the countersloping glacis.

Objections to Carnot's system

Objections to Carnot's system included that:

Adoption of Carnot's ideas in continental Europe

The Austrians built impressive fortifications in the 1830s, using Carnot's ideas, at Verona in Italy. These consisted of massive ramparts with a Carnot wall at their foot.[19] In the same period the Russians used the walls in fortifying Warsaw.[19] In Germany examples were built at Coblenz[20] and Ulm.[21]

The Woolwich experiments

Whilst the Carnot wall was extensively employed in fortifications in continental Europe there was resistance to its use in Britain, for the reasons stated above.[4]

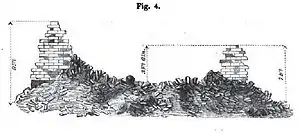

In 1823 a replica Carnot wall was constructed at Woolwich, Kent to test Carnot's theories. This wall was 21 feet (6.4 m) high and 22 feet (6.7 m) long. The tapering wall was 7 feet (2.1 m) thick at its base and 6 feet (1.8 m) thick at the top.[22] A rampart of equal height with the wall was built in front of it to represent that of a real fort.[23] The idea was that the gunners would be unable to see the wall itself when firing.

Experiments with this wall took place in August 1824. Their object was to test whether artillery at a distance could breach the walls by firing at high angles.[22] Those conducting the experiments concluded that the wall could be severely damaged even if the besiegers' gunners could not see it.[24] However it was objected that the Woolwich experiments did not really prove what was claimed. The tests used far more artillery fire than would be likely to be possible in a real siege.[25]

Later British forts with a Carnot wall

The objectors did not hold sway indefinitely however and forts with Carnot walls were eventually built in Britain. In his 1849 book James Fergusson outlined the advantages of the Carnot wall, though without wholly endorsing its use.[26] He said that such walls would be cheaper to construct. They would last longer than the usual scarp wall with a "mass of earth at its back always tending to overthrow it". In addition it would be difficult to scale the wall as the besiegers would have to use ladders to reach the top and the same ladders to descend the other side, while all the time facing assault by defenders.[26] Fergusson also commented that the 1824 Woolwich experiments, which had influenced subsequent fort design, had given "every possible advantage in favour of the attack".[27] He argued that, even were a breach to be made in the wall, the defenders could easily attack the besiegers, making an assault on the fort hazardous. His final point was that in any case the wall would be hidden behind a rampart far higher, in relation to the height of the wall, than that at Woolwich, so that the enemy artillery would be not able to significantly damage it.[27]

The first fort to be built in Britain with a Carnot wall was in 1854 at the mouth of the river Arun at Littlehampton in West Sussex. This was 12 feet (3.7 m) high with open-angled bastions.[28] In 1857 a very similar fort was constructed at Shoreham along the coast from Littlehampton. The wall there included Caponiers, as also advocated by Carnot.[29] Following the Royal Commission on the Defence of the United Kingdom of 1859 several forts with Carnot walls were built. These included:

- Sandown Barrack Battery, Isle of Wight[30]

- Redcliff Battery, Isle of Wight[31]

- Yaverland Battery, Isle of Wight[32]

- Shotley Battery, Harwich, Essex[33]

- Woodlands Fort, Plymouth, Devon

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Saunders 1989, p. 155.

- ↑ Duffy 1975, p. 52.

- ↑ Douglas 1859, p. 103.

- 1 2 Douglas 1859, p. 83.

- ↑ Saunders 1989, p. 158.

- ↑ Carnot 1814

- ↑ Duffy 1975, p. 9

- ↑ Duffy 1975, p. 16.

- ↑ Saunders 1989, p. 156.

- 1 2 Carnot 1814, p. 204.

- ↑ Carnot 1814, p. 197.

- ↑ Barras 2011

- ↑ Duffy 1975, pp. 59–63.

- ↑ Douglas 1859, p. 81.

- ↑ Douglas 1859, p. 148.

- ↑ Lendy 1862, p. 453.

- ↑ Douglas 1859, p. 111.

- ↑ Lendy 1862, p. 449.

- 1 2 Hughes 1974, p. 171.

- ↑ Douglas 1859, p. 125.

- ↑ Hughes 1974, p. 169.

- 1 2 Douglas 1859, p. 96.

- ↑ Douglas 1859, p. 97.

- ↑ Douglas 1859, p. 99.

- ↑ Lloyd 1887, p. 194.

- 1 2 Fergusson 1849, p. 54.

- 1 2 Fergusson 1849, p. 55.

- ↑ Goodwin 1985, p. 36.

- ↑ Goodwin 1985, p. 45.

- ↑ Historic England. "Sandown Barrack Battery (1019195)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- ↑ Palmerston Forts Society. "Redcliff Battery" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- ↑ Isle of Wight History Centre. "Yaverland Battery". Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2012-01-31.

- ↑ Victorian Forts. "Shotley Point Battery" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-01-31.

Bibliography

Barras, Simon (2011). "An Introduction to Artillery Fortification" (PDF). Fortress Study Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

Carnot, Lazare (1814). A treatise on the defence of fortified places: Written under the direction and published by command of Buonaparte, for the instruction and guidance of the officers of the French Army. London: Printed for T. Egerton.

Douglas, Sir Howard (1859). Observations on modern systems of fortification: including that proposed by M. Carnot, and a comparison of the polygonal with the bastion system; to which are added, some reflections on intrenched positions, and a tract on the naval, littoral, and internal defence of England. London: J. Murray.

Duffy, Christopher (1975). Fire & Stone: The Science of Fortress Warfare 1660-1860 (First ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles.

Fergusson, James (1849). An essay on a proposed new system of fortification: with hints for its application to our national defences. London: J. Weale.

Goodwin, John (1985-11-09). The Military Defence of West Sussex (1st ed.). Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 0-906520-23-1.

Hughes, Quentin (1974). Military Architecture. Beaufort Publishing. ISBN 1-85512-008-9.

Lendy, Auguste Frederic (1862). Treatise on fortification: or, Lectures delivered to officers reading for the staff. London: W. Mitchell.

Lloyd, Ernest Marsh (1887). Vauban, Montalembert, Carnot: Engineer studies. London: Chapman and Hall.

Saunders, A D (1989). Fortress Britain: Artillery Fortification in the British Isles and Ireland. Liphook: Beaufort Publishing. ISBN 1-85512-000-3.

Yule, Sir Henry (1851). Fortification for officers of the army and students of military history. London.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- Victorian Forts and Artillery Retrieved 2012-01-15

- The Palmerston Forts Society Retrieved 2012-01-15

- Shoreham Fort Retrieved 2012-01-15

- Woodlands Fort, Plymouth Retrieved 2012-01-15