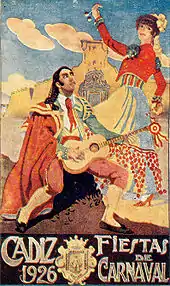

| Carnival of Cádiz | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Carnival of Cádiz 2018 | |

| Genre | Carnival |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Location(s) | Cádiz, Spain |

| Inaugurated | 16th century |

| Fiesta of International Tourist Interest | |

| Designated | 1980 |

The Carnival of Cádiz (Spanish: Carnaval de Cádiz) is one of the best-known carnivals in Spain. Its main characteristic is humor. Through sarcasm, mockery and irony, the main groups and the people of the street "purge" the most pressing problems of today.[1] The whole city participates in the carnival for more than two weeks each year, and the presence of this fiesta is almost constant in the city because of the recitals and contests held throughout the year.

The main characteristics of the carnival in Cádiz are the acerbic criticisms, the droll plays on words, stinging sarcasm, and the irreverence of parody.[2] While some carnivals elsewhere in the world stress the spectacular, the glamorous, or the scandalous in costumes, Cádiz distinguishes itself with how clever and imaginative its carnival attire is. It is traditional to paint the face as a humble substitute for a mask.

On Saturday, everyone wears a costume, which, many times, is related to the most polemical aspects of the news. However, the Carnival of Cádiz is most famous for the satirical groups of performers called chirigotas. Their music and their lyrics are in the center of the carnival.

Carnival of Cádiz is a sociological phenomenon of special singularity. Its historical evolution, from its most remote origins until today, has endowed it with a marked rebellious character. In addition, the development of their groups (mainly their choirs, chirigotas, comparsas and quartets) differentiates them from other carnivals in the world and also identifies them as a communicational phenomenon. It is a vehicle that generates information, opinion and entertainment, but also in its subversive nature, in its condition of counter-power.[3]

History

The first references to the carnivals of Cádiz that are known come from the sixteenth century. In the process of its own organisation, the Cadiz Carnival takes on peculiarities of Italian, explicable by the fundamentally Genoese influence that Cádiz knew since the fifteenth century. After the Turks' displacement to the Mediterranean, Italian merchants moved to the West, finding Cádiz a place of settlement perfectly communicated with the commercial objectives that the Genoese were looking for: the north and center of Africa. The masks, the serpentines, the confetti are assimilated from the Italian carnival.

16th century

The first documentary references to the celebration of the carnival are from historian Agustín de Horozco. At the end of the 16th century, during carnival time, the inhabitants of Cadiz plucked the flowers from the pots to throw them at each other as a joke. Other documents that record the celebration of the carnivals are the Synod Constitutions of 1591 and the Statutes of the Seminary of Cádiz in 1596, both contain indications so that the religious did not participate in the festivities in a way that the seculars did. These references, about the Carnival, confirm that already at the end of the 16th century, the festivities should have deep roots among the people of Cadiz.[4]

17th century

There are also references from the seventeenth century. A document of 1636 recognizes the impotence of the civil power against the popular celebration. A letter from General Mencos dated in Cádiz on February 7, 1652, complains that the Cadiz workers refused to repair their boat because they were in Carnestolendas. There is also evidence of the events that took place in 1678, the year in which the cleric Nicolás Aznar was accused of having adulterous relations with Antonia Gil Morena, whom he had met during the carnival.[5]

18th century to 20th century

Beginning the 18th century, the orders are repeated frequently, trying to banish the Carnival. In 1716 masked dances were prohibited by the Crown, prohibitions that were repeated throughout this century. In spite of everything, there are testimonies that confirm the disrespect of the orders was quite remarkable. In the carnival of 1776, excesses were committed in the convent of Santa María and in that of Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria, which caused scandals in the city. This same year, the British traveler Henry Swinburne visited the city, who left testimony about the Carnival celebrations of the people of Cadiz.[6]

These festivities were celebrated even during the French invasion. However, there was a time during which the celebration was suspended: on February 5, 1937, during the Civil War and the Battle of the Ebro, the prohibition to celebrate any type of carnival in Spain was published in the “Boletín Oficial del Estado”.[7]

It was not until 1947 when the tradition was recovered, a fact that occurred as a result, paradoxically, of a disgrace: the explosion of the San Severiano storage depot, who caused some 200 victims in the city. The civil governor, Carlos María Rodríguez de Valcárcel, decided then that it was necessary to raise the spirits and was recovered the festive spirit In the organisation of the Carnival.[8]

Musical groups

The most famous groups are the chirigotas, the choirs, and the comparsas.

The comparsas are well-known witty and satiric groups that train for the whole year to sing about politics, topics in the news, and everyday circumstances, while all of the members wear identical costumes. There is an official competition in Teatro Falla, where many of them compete for a group award. Their songs are all original compositions and are full of satire and wit. Each comparsa – whether a professional group or one made up of family members, friends or colleagues – has a wide repertoire of songs. They sing in the streets and squares, at improvised venues like outdoor staircases or portals, and in established open-air tablaos (tableaux) organized by the carnival clubs.

The chirigotas are the groups of people (like the comparsas) that sharing a costume and singing together, performed a full repertoire of songs about current topics but with in a humoristic way, unlike the comparsas. The chirigotas´ tunes are happier as well as their lyrics even though they can address the same subjects as the comparsas. They also compete in the Teatro Falla for the awards.

The choirs (coros) are larger groups that travel through the streets on open flat-bed carts or wagons, singing, with a small ensemble of guitars and lutes. Their characteristic composition is the "Carnival Tango", and they alternate between comical and serious repertory, with special emphasis on lyrical homages to the city and its people. The costumes are, by far, the most sophisticated and elaborate of all.

Other groups can be found in the streets: the quartets (cuartetos), that, oddly, can be composed of five, four, or three members. They do not bring a guitar, only a kazoo and two sticks, that they use to mark the rhythm. They use set-piece theater scenes (pre-written skits), improvisations, and music, and they are purely comical.

The minimalist carnival groups in Cádiz are the romanceros, perhaps the oldest, and, certainly, the most invariant carnival representation in Cádiz throughout history. A romancero is a single costumed person who brings a big easel on which posters help him to tell a story with images. The romancero recites humorous verses while pointing at aspects of the pictures and drawings with a long stick.

Musical forms

Specific musical forms have evolved at the Carnival of Cádiz over the years. In the beginning, popular music was used, and tropical rhythms were mixed with popular European dances and songs; only the lyrics changed. Near the end of the nineteenth century, the musical identity of the Carnival was already mature, and, although most of the names (tango, pasodoble, couplet, etc.) are shared with other musical forms around the world, their melodies, rhythms, and character are unmistakably original.

- The Presentation is the first piece sung to present the characterisation of the group, called its tipo. The style of the music is absolutely free and unstructured. It can take the form of a well-known form, an original composition, or even a spoken-word recitation.

- The Couplet is sung by the chirigotas, comparsas, choirs, and quartets. They are short satirical songs with a refrain that is always related to the costume and the characterisation (tipo) of the group.

- The Pasodoble is a longer song without a refrain, and it is usually (but not always) serious, criticising something that happened during the previous year or rendering an homage to someone. They are sung by the comparsas and the chirigotas.

- The Tango, with its characteristic gaditano rhythm is sung only by the choirs, accompanied by their orchestras, and they are mostly poetical compositions.

- The Potpourri, sung by all of the groups, changing the lyrics of well-known songs of the year or any other kind of music, sometimes depending on the group's tipo.

Beside these, other musical forms, including short improvisations and theatrical skits are featured, mostly by the so-called illegal chirigotas, murgas, or callejeras, that don't submit to any rule or contest. They just roam the streets singing and performing as they wish.

The contests

The best known contest among chirigotas, choirs, comparsas, and quartets in Cádiz is the 'Official Contest' at the Gran Teatro Falla, that finishes just before the first Saturday of Carnival. It is broadcast by the regional television and radio stations. Other contests take place before, during, and after the Carnival, usually organized by institutions and private clubs, and their venues are open tablaos in the public squares (plazas) of the city.

References

- ↑ El País (12 february, 2018)

- ↑ PAYÁN SOTOMAYOR, P. (1983). El habla de Cádiz en las letras de su Carnaval. Carnaval en Cádiz, 65-85.

- ↑ Sacaluga Rodríguez, I. (2014). El Carnaval de Cádiz como generador de información, opinión y contrapoder: análisis crítico de su impacto en línea y fuera de línea (Doctoral dissertation).

- ↑ Agustín de Orozco (1845) Historia de la ciudad de Cádiz: Imprenta de don Manuel Bosch, 1845. Hay ed. moderna de Arturo Morgado García, 2001.

- ↑ Cuadrado, U., & Barbosa, F. (1999). El Carnaval de Cádiz. Orígenes y evolución: Siglos XVI-XIX.

- ↑ Swinburne, H. (1787) "Travels through Spain in the years 1775 and 1776" Biblioteca Virtual de Andalucía, online consultation 14 March, 2018

- ↑ Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE), February 5, 1937.

- ↑ "El carnaval de Cádiz prohibido durante la Guerra Civil"