| Cañadón Asfalto Basin | |

|---|---|

| Cuenca de Cañadón Asfalto | |

Location of the basin in Argentina | |

| Coordinates | 42°51′S 67°56′W / 42.850°S 67.933°W |

| Location | Southern South America |

| Region | Patagonia |

| Country | |

| State(s) | Chubut & Río Negro Provinces |

| Cities | Gastre, Paso del Sapo |

| Characteristics | |

| On/Offshore | Onshore |

| Boundaries | North Patagonian Massif (N & E), Cotricó High (S), Ñirihuau Basin (W) |

| Part of | Southern Atlantic rift basins |

| Area | ~80,000 km2 (31,000 sq mi) |

| Hydrology | |

| River(s) | Chico River, Chubut River |

| Lake(s) | Gran Laguna Salada, Laguna del Hunco |

| Geology | |

| Basin type | Rift |

| Plate | South American |

| Orogeny | Opening of the South Atlantic (Mesozoic) Andean (Cenozoic) |

| Age | Early Jurassic-Quaternary |

| Stratigraphy | Stratigraphy |

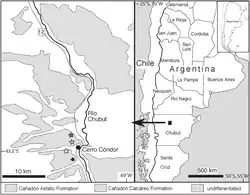

The Cañadón Asfalto Basin (Spanish: Cuenca de Cañadón Asfalto) is an irregularly shaped sedimentary basin located in north-central Patagonia, Argentina. The basin stretches from and partly covers the North Patagonian Massif in the north, a high forming the boundary of the basin with the Neuquén Basin in the northwest, to the Cotricó High in the south, separating the basin from the Golfo San Jorge Basin. It is located in the southern part of Río Negro Province and northern part of Chubut Province. The eastern boundary of the basin is the North Patagonian Massif separating it from the offshore Valdés Basin and it is bound in the west by the Patagonian Andes, separating it from the small Ñirihuau Basin.

The basin started forming in the Early Jurassic, with the break-up of Pangea and the creation of the South Atlantic, when extensional tectonics, including rifting, formed several basins in eastern South America and southwestern Africa. The accommodation space in the Cañadón Asfalto Basin was filled by volcanic, fluvial and lacustrine deposits in various geologic formations, separated by unconformities related to transtensional and transpressional tectonic forces. The Cenozoic evolution of the basin is mainly influenced by the Andean orogeny, producing folding and faulting in the basin.

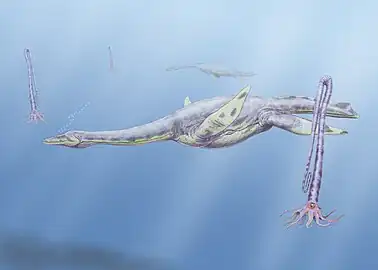

The basin is of paleontological significance as it hosts several fossiliferous stratigraphic units providing many fossils of dinosaurs, turtles, mammals, plesiosaurs, pterosaurs, crocodylomorphs, fish, amphibians and flora in the Mesozoic and mammals, amphibians, fish and flora in the Cenozoic. The Collón Curá Formation, that is also present in the southern Neuquén Basin, is the defining formation for the Colloncuran, used within the SALMA classification, the geochronology for the Cenozoic used in South America.

Description

The Cañadón Asfalto Basin was not defined as a separate sedimentary basin until the 1990s. Until then, the sediments deposited in the basin were considered part of the North Patagonian Massif. Homovc et al. (1991) and Figari & Courtade (1993) started defining the stratigraphic units in megasequences indicative of the evolution of a rift basin, resulting from the break-up of Pangea and Gondwana in particular.[1]

The basin has an irregular shape, comprising several depocenters defining sub-basins. The basin stretches from and partly covers the North Patagonian Massif in the north and east towards the Cotricó High to the south of the Paso del Sapo Sub-basin, separating the Cañadón Asfalto Basin from the Golfo San Jorge Basin in the south. In the west, the basin is bound by uplifted areas with the small Ñirihuau Basin.[2]

The area of the basin is sparsely populated, with Gastre and Paso del Sapo representing some of the few villages in the basin. The Chubut River crosses the basin in the south in the Altar Valley.

Basin evolution

The Cañadón Asfalto Basin started forming in the earliest Jurassic on top of Permian basement constituted by the igneous-metamorphic Mamil Choique and Cushamen Formations.[3] Two main phases of basin evolution are recognized; the Jurassic and Cretaceous megasequences. Figari et al. in 2015 describe two Jurassic megasequences, J1 in the Early Jurassic and J2 in the Late Jurassic. During these phases, the basin went through an extensional tectonic regime, with transtensional movements. Several distinct tectonic reactivation cycles occurred, with block rotation due to transpressional forces. The geodynamic movements are noted in the stratigraphy by regional unconformities. The predominantly extensional movement was overprinted by a compressional setting, active since the early Cenozoic. This compressional phase is noted in folds and compressional faults present in the basin.[4]

The sedimentary infill of the Early and Middle Jurassic in the basin is characterized by fluvial and lacustrine sediments of the Las Leoneras, Cañadón Asfalto and Cañadón Calcáreo Formations covering the volcanic Lonco Trapial Formation, which comprises intermediate volcanic rocks sourced by magmas coming from the mantle. This succession is unconformably covered by lacustrine, fluvial and volcaniclastic rocks of the approximately 10 to 15 million year ranging Chubut Group comprising the older Los Adobes Formation and the younger Cerro Barcino Formation. The western side of the basin during the Late Cretaceous experienced a marine transgression of the Atlantic Ocean, depositing the fluvial and estuarine Paso del Sapo and Lefipán Formations.[5]

The marine sediments of the Lefipán Formations have been correlated to the Salamanca Formation of the Golfo San Jorge Basin to the south and the Lefipán sediments were sourced from the North Patagonian Massif. To the west of the Cañadón Asfalto Basin, another basin started forming in these times, the Ñirihuau Basin, characterized by the deposition of the felsic to intermediate volcanic Don Juan Formation, the basaltic Tres Picos Prieto Formation and the Huitrera Formation. In the Ñirihuau Basin, this sequence is covered by the Oligocene to Miocene Ventana Formation.[6]

During the Paleogene, in the Cañadón Asfalto Basin the volcaniclastic Laguna del Hunco Formation,[7] and volcanic Sarmiento Group were deposited.[8] The Neogene succession in the basin comprises the Early Miocene alluvial volcaniclastics of the La Pava Formation,[8][9] and the Middle to Late Miocene volcaniclastic, fluvial, lacustrine and deltaic tuffs, sandstones and carbonates of the Collón Curá Formation.

The Late Miocene to Quaternary succession comprises mostly the basaltic lava flows[10] of the El Mirador Formation,[11] the basalts of the Cráter Formation, and Quaternary alluvium.[12][13] In the northern part of the basin, the Late Miocene and Early Pliocene is represented by the fluvial, marine and eolian Río Negro Formation, a formation extending into the Colorado Basin.[14][15]

Stratigraphy

The stratigraphy of the Cañadón Asfalto Basin covers the following units:

| Age | Group | Formation | Sequence | Environment | Maximum thickness | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary | alluvium | |||||

| Mid-Late Pleistocene | Cráter | Basalt | 3 m (9.8 ft) | [16] | ||

| Early Pliocene | Río Negro | Eolian, fluvial & marine | [14] | |||

| Late Miocene | ||||||

| El Mirador | Volcanic | [11] | ||||

| Colloncuran | Collón Curá | Fluvial, lacustrine, deltaic | 300 m (980 ft) | [8] | ||

| Early Miocene | La Pava | Alluvial volcaniclastic | 15 m (49 ft) | [8][9] | ||

| Sarmiento | Volcanic | [8] | ||||

| Late Eocene | ||||||

| Early Eocene | Laguna del Hunco | Volcaniclastic | [7] | |||

| Late Paleocene | Hiatus | |||||

| Danian | Barda Colorada | Volcaniclastic | [17] | |||

| Lefipán | Tidal & shallow marine | 380 m (1,250 ft) | [17] | |||

| Maastrichtian | ||||||

| La Colonia | Tidal & shallow marine | 240 m (790 ft) | [18] | |||

| Paso del Sapo | Estuarine & shallow marine | 150 m (490 ft) | [17] | |||

| Campanian | ||||||

| Santonian | Hiatus | |||||

| Coniacian | ||||||

| Turonian | ||||||

| Cenomanian | ||||||

| Albian | Chubut | Cerro Barcino | K | Fluvial, alluvial, lacustrine | [19] | |

| Aptian | ||||||

| Barremian | Los Adobes | Alluvial & fluvial | [20] | |||

| Hauterivian | Hiatus | |||||

| Valanginian | ||||||

| Berriasian | ||||||

| Tithonian | Sierra de Olte | Cañadón Calcáreo | J2 | Fluvial & lacustrine | [21] | |

| Kimmeridgian | ||||||

| Oxfordian | ||||||

| Callovian | Hiatus | |||||

| Bathonian | ||||||

| Bajocian | Cañadón Asfalto | J1 | Lacustrine carbonate platform | 600 m (2,000 ft) | [22][23] | |

| Aalenian | ||||||

| Toarcian | ||||||

| Lonco Trapial | Volcaniclastic | 800 m (2,600 ft) | [24][25] | |||

| Pliensbachian | ||||||

| Sinemurian | ||||||

| Hettangian | Las Leoneras | Fluvial & lacustrine | 372 m (1,220 ft) | [26][27] | ||

| Triassic | Hiatus | |||||

| Paleozoic | Basement | Mamil Choique & Cushamen | [28][29] | |||

Paleontological significance

The Cañadón Asfalto Basin has provided several fossils of various groups of flora and fauna. One of the largest dinosaurs known, the titanosaur Patagotitan mayorum, and one of the largest theropods, Tyrannotitan chubutensis, were found in the Cerro Barcino Formation.[30][31] Fossils of Leonerasaurus taquetrensis, an early Sauropodomorph, were found in and named after the Las Leoneras Formation.[32] The La Colonia Formation has provided fossils of a mammal; Argentodites coloniensis,[33] and a nearly complete skeleton of the theropod Carnotaurus sastrei. Remains of the plesiosaur Aristonectes parvidens were found in the Maastrichtian section of the Lefipán Formation.[34]

Fossil flora (pollen, spores, algae and macroflora) have been recovered from the Lonco Trapial Formation (Cupressaceae),[35] and the Cañadón Asfalto Formation and comprise several families of plants, indicative of climatic conditions in the Late Jurassic; Osmundaceae, Caytoniaceae, Araucariaceae, Cheirolepidiaceae, Podocarpaceae, Botryococcaceae, Zygnemataceae, Prasinophyceae, Filicales and Taxodiaceae.[36] The same formation also provided fossils of two species of the frog Notobatrachus,[37] the turtle Condorchelys antiqua,[38] the pterosaur Allkaruen koi,[39] and several mammals.[40]

Fossil fish of Condorlepis groeberi were retrieved from the Cañadón Calcáreo Formation,[41] and the crocodylomorphs Almadasuchus figarii (Cañadón Calcáreo Formation),[42] and Barcinosuchus gradilis (Cerro Barcino Formation),[43] come from the Mesozoic strata in the basin.

Fossil leaves of Lefipania padillae and Araucaria lefipanensis come from and were named after the latest Maastrichtian within the Lefipán Formation.[44][45] The Paleocene (Tiupampan) strata of the Lefipán Formation have provided fossils of the mammal Cocatherium lefipanum and fish Hypolophodon patagoniensis.[46][47]

The Early Eocene (Casamayoran to Mustersan) Laguna del Hunco Formation has provided fossils of the fish Bachmannia chubutensis,[48] the frog Shelania pascuali,[49] and fossil flora.[50]

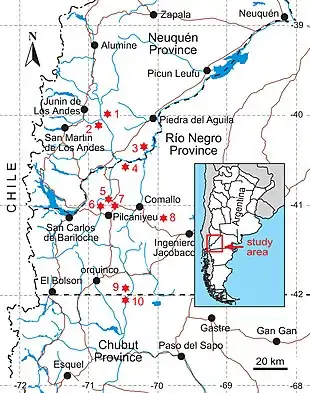

The Collón Curá Formation, that defines the Colloncuran South American land mammal age, stretches across the Neuquén Basin to the northwest of the North Patagonian Massif and the western part of the Cañadón Asfalto Basin. The formation has provided many mammal, reptile and bird fossils, among which the largest terror bird Kelenken.[51] Along the Chico River in the basin (localities 9 and 10 on the map), fossils of the sparassodont Patagosmilus goini, two new species of Protypotherium,[52] and the rodents Guiomys unica and Microcardiodon williensis were found.[53][54][55]

See also

References

- ↑ Figari et al., 2015, p.137

- ↑ Figari et al., 2015, p.138

- ↑ Di Pietro, 2016, p.28

- ↑ Di Pietro, 2016, p.23

- ↑ Echaurren, 2017, p.94

- ↑ Echaurren, 2017, p.95

- 1 2 Figari et al., 2015, p.154

- 1 2 3 4 5 Figari et al., 2015, p.155

- 1 2 Di Pietro, 2016, p.46

- ↑ Echaurren et al., 2016, p.103

- 1 2 Echaurren et al., 2016, p.102

- ↑ Echaurren et al., 2016, p.105

- ↑ Echaurren, 2017, p.102

- 1 2 Pérez, 2012, p.7

- ↑ Pérez, 2012, p.10

- ↑ Di Pietro, 2016, p.49

- 1 2 3 Figari et al., 2015, p.153

- ↑ Gasparini et al., 2015

- ↑ Figari et al., 2015, p.152

- ↑ Figari et al., 2015, p.151

- ↑ Figari et al., 2015, p.147

- ↑ Figari et al., 2015, p.146

- ↑ Di Pietro, 2016, p.42

- ↑ Figari et al., 2015, p.144

- ↑ Di Pietro, 2016, p.39

- ↑ Figari et al., 2015, p.142

- ↑ Di Pietro, 2016, p.31

- ↑ Figari et al., 2015, p.143

- ↑ Olivera et al., 2015, p.3

- ↑ Carballido et al., 2017

- ↑ Novas et al., 2005

- ↑ Pol et al., 2011

- ↑ Kielan-Jaworowska et al., 2007, p.257

- ↑ Gasparini et al., 2003

- ↑ Escapa et al., 2008a

- ↑ Olivera et al., 2015, p.6

- ↑ Escapa et al., 2008b

- ↑ Sterli, 2008

- ↑ Codorniú et al., 2016

- ↑ Gaetano & Rougier, 2011

- ↑ López Arbarello et al., 2013

- ↑ Pol et al., 2013

- ↑ Leardi & Pol, 2009

- ↑ Martínez et al., 2018

- ↑ Andruchow‐Colombo et al., 2018

- ↑ Cione et al., 2013

- ↑ Goin et al., 2006

- ↑ Azpelicueta & Cino, 2011

- ↑ Báez & Trueb, 1997

- ↑ Wilf et al., 2005

- ↑ Bertelli et al., 2007

- ↑ Vera et al., 2017, p.855

- ↑ Forasiepi & Carlini, 2010

- ↑ Pérez, 2010

- ↑ Pérez & Vucetich, 2011

Bibliography

- General

- Echaurren González, Andrés. 2017. Evolución tectónica del sistema orogénico Andino en la Patagonia norte (42-44° S) (PhD thesis), 1–170. Universidad de Buenos Aires. Accessed 2019-02-27.

- Echaurren, A.; A. Folguera; G. Gianni; D. Orts; A. Tassara; A. Encinas; M. Giménez, and V. Valencia. 2016. Tectonic evolution of the North Patagonian Andes (41°–44° S) through recognition of syntectonic strata. Tectonophysics 677–678. 99–114. Accessed 2019-02-27.

- Figari, Eduardo G.; Roberto A. Scasso; Rubén N. Cúneo, and Ignacio Escapa. 2015. Estratigrafía y evolución geológica de la Cuenca de Cañadón Asfalto, Provincia del Chubut, Argentina. Latin American Journal of Sedimentology and Basin Analysis 22. 135–169. Accessed 2018-09-10.

- Gasparini, Zulma; Juliana Sterli; Ana Parras; José Patricio O'Gorman; Leonardo Salgado; Julio Varela, and Diego Pol. 2015. Late Cretaceous reptilian biota of the La Colonia Formation, central Patagonia, Argentina: Occurrences, preservation and paleoenvironments. Cretaceous Research 54. 154–168. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Pérez, Mariano. 2012. Análisis paleoambiental del miembro superior de la Formación Río Negro (Mioceno-Plioceno de Patagonia septentrional): un ejemplo de interacción fluvio-eólica compleja (BSc. thesis), 1–47. Universidad Nacional de La Pampa. Accessed 2018-09-10.

- Di Pietro, Pablo Federico. 2016. Geología de la zona del Cerro Bayo, Bajo de Gastre, Provincia de Chubut (B.S. thesis), 1–107. Universidad de Buenos Aires. Accessed 2019-02-27.

- Paleontology

- Andruchow‐Colombo, Ana; Ignacio H. Escapa; N. Rubén Cúneo, and María A. Gandolfo. 2018. Araucaria lefipanensis (Araucariaceae), a new species with dimorphic leaves from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina. American Journal of Botany 105(6). 1067–1087. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Azpelicueta, M.M., and A.L. Cione. 2011. Redescription of the Eocene Catfish Bachmannia chubutensis (Teleostei: Bachmanniidae) of Southern South America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31. 258–269. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Báez, A.M., and L. Trueb. 1997. Redescription of the Paleogene Shelania pascuali from Patagonia and its bearing on the relationships of fossil and Recent pipoid frogs. Scientific Papers, Natural History Museum, University of Kansas 4. 1–41. Accessed 2019-03-01. Archived 2019-03-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Bertelli, Sara; Luis M. Chiappe, and Claudia Tambussi. 2007. A New Phorusrhacid (Aves: Cariamae) from the Middle Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(2). 409–419. Accessed 2019-02-27.

- Carballido, J.L.; D. Pol; A. Otero; I.A. Cerda; L. Salgado; A.C. Garrido; J. Ramezani; N.R. Cúneo, and J.M. Krause. 2017. A new giant titanosaur sheds light on body mass evolution among sauropod dinosaurs. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 284(1860). 20171219. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Cione, Alberto Luis; Marcelo Tejedor, and Francisco Javier Goin. 2013. A new species of the rare batomorph genus Hypolophodon (?latest Cretaceous to earliest Paleocene, Argentina). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 267(1). 1–8. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Codorniú, L.; A.P. Carabajal; D. Pol; D. Unwin, and O.W.M Rauhut. 2016. A Jurassic pterosaur from Patagonia and the origin of the pterodactyloid neurocranium. PeerJ 4. e2311. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Escapa, I.H.; N.R. Cúneo, and B. Axsmith. 2008a. A new genus of the Cupressaceae (sensu lato) from the Jurassic of Patagonia: Implications for conifer megasporangiate cone homologies. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 151. 110–122. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Escapa, I.H.; J. Sterli; D. Pol, and L. Nicoli. 2008b. Jurassic Tetrapods and Flora of Cañadon Asfalto Formation in Cerro Cóndor Area, Chubut Province. Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 63(4). 613–624. Accessed 2019-03-01. Archived 2014-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Forasiepi, A.M., and A.A. Carlini. 2010. A new thylacosmilid (Mammalia, Metatheria, Sparassodonta) from the Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Zootaxa 2552. 55–68. Accessed 2019-02-27.

- Gaetano, L.C., and G.W. Rougier. 2011. New materials of Argentoconodon fariasorum (Mammaliaformes, Triconodontidae) from the Jurassic of Argentina and its bearing on triconodont phylogeny. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31(4). 829–843. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Gasparini, Z.; N. Bardet; J.E. Martin, and M.S. Fernandez. 2003. The elasmosaurid plesiosaur Aristonectes Cabreta from the Latest Cretaceous of South America and Antarctica. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23. 104–115. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Goin, Francisco; Rosendo Pascual; Marcelo F. Tejedor; Javier N. Gelfo; Michael O. Woodburne; Judd A. Case; Marcelo A. Reguero; Mariano Bond, and Guillermo M. López, Alberto L. Cione, Daniel Udrizar Sautheir, Lucía Balarino, Roberto A. Scassos, Francisco A. Medina and María C. Ubaldón. 2006. The earliest Tertiary therian mammal from South America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26. 505–510. Accessed 2017-10-26.

- Kielan-Jaworowska, Z.; E. Ortiz Jaureguizar; C. Vieytes; R. Pascual, and F.J. Goin. 2007. First ?cimolodontan multituberculate mammal from South America. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 52. 257–262. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Leardi, Juan Martín, and Diego Pol. 2009. The first crocodyliform from the Chubut Group (Chubut Province, Argentina) and its phylogenetic position within basal Mesoeucrocodylia. Cretaceous Research 30(6). 1376–1386. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- López Arbarello, Adriana; Emilia Sferco, and Oliver W.M. Rauhut. 2013. A new genus of coccolepidid fishes (Actinopterygii, Chondrostei) from the continental Jurassic of Patagonia. Palaeontologia Electronica 16(1). 7A. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Martínez, Camila; María A. Gandolfo, and N. Rubén Cúneo. 2018. Angiosperm leaves and cuticles from the uppermost Cretaceous of Patagonia, biogeographic implications and atmospheric paleo-CO2 estimates. Cretaceous Research 89. 107–118. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Novas, F.E.; S. De Valais; P. Vickers-Rich, and T. Rich. 2005. A large Cretaceous theropod from Patagonia, Argentina, and the evolution of carcharodontosaurids. Naturwissenschaften 92(5). 226–230. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Pérez, M.E., and M.G. Vucetich. 2011. A new Extinct Genus of Cavioidea (Rodentia, Hystricognathi) from the Miocene of Patagonia (Argentina) and the Evolution of Cavoid Mandibular Morphology. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 18. 163–183. Accessed 2019-02-27.

- Pérez, M.E.. 2010. A new rodent (Cavioidea, Hystricognathi) from the middle Miocene of Patagonia, mandibular homologies, and the origin of the crown group Cavioidea sensu stricto. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30. 1848–1859. Accessed 2019-02-27.

- Pol, Diego; Oliver W. M. Rauhut; Agustina Lecuona; Juan M. Leardi; Xing Xu, and James M. Clark. 2013. A new fossil from the Jurassic of Patagonia reveals the early basicranial evolution and the origins of Crocodyliformes. Biological Reviews 88(4). 862–872. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Pol, Diego; Alberto Garrido, and Ignacio A. Cerda. 2011. A New Sauropodomorph Dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of Patagonia and the Origin and Evolution of the Sauropod-type Sacrum. PLoS ONE 6(1). e14572. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Sterli, J. 2008. A new, nearly complete stem turtle from the Jurassic of South America with implications for turtle evolution. Biology Letters 4. 286–289. Accessed 2019-03-01.

- Vera Nardoni, Bárbara; Marcelo Reguero, and Laureano González Ruiz. 2017. The Interatheriinae notoungulates from the middle Miocene Collón Curá Formation in Argentina. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62(4). 845–863. Accessed 2019-02-27.

- Wilf, Peter; Kirk R. Johnson; N. Rubén Cúneo; M. Elliot Smith; Bradley S. Singer, and Maria A. Gandolfo. 2005. Eocene Plant Diversity at Laguna del Hunco and Río Pichileufú, Patagonia, Argentina. The American Naturalist 135. 634–650. Accessed 2017-10-26.

Further reading

- Bally, A.W., and S. Snelson. 1980. Realms of subsidence. Canadian Society for Petroleum Geology Memoir 6. 9–94. .

- Kingston, D.R.; C.P. Dishroon, and P.A. Williams. 1983. Global Basin Classification System. AAPG Bulletin 67. 2175–2193. Accessed 2017-06-23.

- Klemme, H.D. 1980. Petroleum Basins - Classifications and Characteristics. Journal of Petroleum Geology 3. 187–207. .

- Zaffarana, Claudia Beatriz. 2011. Estudio de la deformación precretácica en la región de Gastre, sector sur del Macizo Norpatagónico (PhD thesis), 1–312. Universidad de Buenos Aires. Accessed 2019-03-02.