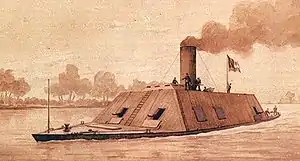

A drawing of C. S. S. Arkansas by R. G. Skerrett | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Arkansas |

| Namesake | State of Arkansas |

| Ordered | August 24, 1861 |

| Builder | John T. Shirley, Memphis, Tennessee |

| Cost | CS$76,920 |

| Laid down | October 1861 |

| Launched | April 1862 |

| Commissioned | April 25, 1862 |

| Fate | Destroyed by her crew, August 6, 1862 |

| General characteristics (1862) | |

| Class and type | Arkansas-class ironclad |

| Displacement | 1,200 long tons (1,200 t) (designed) |

| Length | 165 ft (50 m) |

| Beam | 35 ft (11 m) |

| Draft | 11.5 ft (3.5 m) (designed) |

| Speed | 8 miles per hour (13 km/h) |

| Complement | 232 officers and men |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

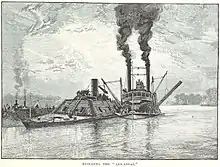

CSS Arkansas was the lead ship of her class of two casemate ironclads built for the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. Completed in 1862, she saw combat in the Western Theater when she steamed through a United States Navy fleet at Vicksburg in July. Arkansas was set on fire and destroyed by her crew after her engines broke down several weeks later. Her remains lie under a levee above Baton Rouge, Louisiana at 30°29′14″N 91°12′5″W / 30.48722°N 91.20139°W.

Design and description

At the outset of the American Civil War, the Confederate States of America had a lack of warships. Seeking to offset the Union's advantage in numbers through technology, Stephen R. Mallory, the Confederate States Secretary of the Navy, decided to build ironclad warships.[1] An experienced steamboat man from Memphis, Tennessee, named John T. Shirley visited Mallory in mid-August 1861 and offered to build a pair of such ships to defend the middle portion of the Mississippi River. Acutely aware of the lack of Confederate naval facilities in the region able to build ironclads, Mallory and Shirley signed a contract for two ships, Arkansas and her sister ship CSS Tennessee, at $76,920 each on August 24.[2] Neither Shirley nor his master builder Primus Emerson owned a facility suitable for building a ship, and none were available for use in Memphis. The pair ultimately settled on a riverfront site below the bluff on which Fort Pickering sat on the southern edge of Memphis[3] where Arkansas was laid down in October 1861.[4]

Shirley consulted with naval architect John L. Porter and gun designer John M. Brooke during his trip and their views greatly influenced the design. Unlike virtually every other Confederate ironclad, the Arkansas-class ships were built with a traditional keeled-hull design with vertical sides to their casemates, probably to improve their seakeeping abilities in the Gulf of Mexico.[5] The ships measured 165 feet (50.3 m) between perpendiculars, had a beam of 35 feet (10.7 m),[6] and a depth of hold of 12 feet (3.7 m).[7] As designed they would have displaced about 1,200 long tons (1,200 t) and had a draft of 11.5 feet (3.5 m).[8] They were equipped with a pair of horizontal direct-acting steam engines, each driving one propeller using steam provided by four coal-burning, high-pressure boilers, although two additional boilers were added to Arkansas while she was under construction. The ship had a maximum speed of 8 miles per hour (13 km/h) in still water, but mechanical problems reduced that speed considerably in service.[9][6] The boiler combustion gases exhausted through a single funnel seven feet (2.1 m) in diameter made from thin iron plates. Although the amount of coal storage aboard the ships is unknown, Arkansas demonstrated a range in excess of 300 miles (480 km) during her brief career.[10]

The Arkansas-class ships were equipped with a pointed cast-iron ram that was bolted to their bows at or just below the waterline. They were designed to mount four guns, two on each broadside, but Arkansas was modified while under construction to accommodate 10 guns, three on each broadside and two each on the fore and aft faces of the casemate. Sources differ as to the exact numbers of each type, but the ship was armed with two 8-inch (203 mm) 64-pounder Columbiads in the front face of the casemate and a pair of 6.4-inch (163 mm) 32-pounder smoothbore guns converted to be rifled cannons in the aft face while the broadside armament consisted of two 9-inch (229 mm) Dahlgren guns and four 32-pounders of which at least two had been rifled, according to naval historian Myron J. Smith.[11][lower-alpha 1] The side gun ports allowed the guns there to traverse somewhat, but the oval gun ports on the fore and aft faces of the casemate were very narrow which badly restricted those guns' ability to traverse and severely limited the ability of the gun crews to see their targets.[14]

The vertical sides of the sisters' casemates were constructed from oak logs two feet (61 cm) thick[15] while the fore and aft faces of the casemate sloped at a 35° angle from the horizontal[16] and were built from 12-inch-thick (305 mm) oak squares to which were nailed oak planks six inches (152 mm) inches thick. Behind the sides of the casemate was a layer of compressed cotton, possibly 20 inches (508 mm) deep, backed by a wooden bulkhead between each gun port. Arkansas was intended to be armored with rolled iron plates, but the only delivery of such plates was diverted to the ironclad CSS Eastport which was much further along in construction. Instead Arkansas used railroad T-shaped-rails, possibly 4 inches (102 mm) deep, alternating top and bottom to present a relatively smooth surface. The pilothouse protruded one or two feet (0.30 or 0.61 m) above the top of the casemate and was protected by two layers of 1-inch (25 mm) bar iron. The visibility of the pilot was badly restricted by the narrow slits cut in the sides of the pilothouse. The casemate roof was minimally protected by 0.5 inches (13 mm) of wrought iron boiler plate and the deck fore and aft of the casemate was unarmored. A shortage of rails meant that the stern face of the casemate was only protected by boiler plates. The broadside gun ports were protected by hinged iron shutters divided into upper and lower halves, but the fore and aft gun ports were fitted with iron collars into which the gun fit when firing.[17] Captain William F. Lynch, commander of Confederate naval forces in the region, described Arkansas as inferior to the ironclad CSS Virginia and criticized the quality and construction of the ship's armor and smokestack.[1]

Construction

Despite his initial support for the Memphis ironclads, Major General Leonidas Polk, the Confederate regional commander, generally refused to release any skilled workmen from his command to assist in their construction; shortly after the ships were laid down, Shirley petitioned Polk for 100 carpenters, but only received 8. Other petitions for manpower were ignored, greatly slowing progress on the ships, as Polk gave priority to his newly formed flotilla of ships on the Tennessee River, all of which except Eastport were unarmored. Material shortages also slowed construction and Shirley chose to focus his efforts on completing Arkansas.[18]

Union ships captured the incomplete Eastport and the lumber and armor plates already delivered, but not yet installed, on February 7, 1862, after the surrender of Fort Henry gave the Federals command of the Tennessee the previous day and towed her way to be completed in a Union shipyard. The beginning of the siege of Island Number Ten north of Memphis in early March threatened the city and alerted Confederate commanders and officials to the lack of progress on the Arkansas-class ironclads. Prompted by the request of Secretary of War, Judah P. Benjamin, Major General P. G. T. Beauregard sent an officer to inspect the sisters and evaluate how much progress had been made in mid-March. He reported that Arkansas was well advanced, but that Tennessee would need six more weeks to before she could be launched. About this time Mallory sent Commander Charles H. McBlair to expedite the ships' construction and appointed him as captain of Arkansas.[19]

The ironclad was apparently launched in early April,[20] although other sources state later in the month.[6][21] At this time, the exterior of her hull had been covered in iron down to 12 inches (305 mm) below the waterline and the casemate had been built although gun ports had not yet been cut. The engines and boilers were aboard, but not yet installed, and the propellers and their shafts had been mounted. Only four guns were available, but McBlair had not yet decided where to mount them. The surrender of Island Number Ten on April 8 left only Fort Pillow between Memphis and the advancing Union forces. Three days later Mallory ordered McBlair to take the Arkansas for completion "if she is in danger at Memphis".[22] McBlair hired the side-wheel steamer Capitol to tow the ironclad if necessary and quartered much of her crew aboard after her arrival on April 19.[23]

On April 25, the same day that the Union captured New Orleans, McBlair commissioned Arkansas and prepared to transfer his ship to Yazoo City, Mississippi, for completion. One or two days later, the ironclad, as well as a barge containing additional materials, were towed by the Capitol to the mouth of the Yazoo River and thence up that river to Yazoo City.[24] The ships left the city on May 7 for Greenwood, Mississippi, which was further upriver, after being warned by Mississippi governor John J. Pettus that Union ships were coming up the Mississippi River, possibly hunting for Arkansas. The two ships reached Greenwood on May 10, just as the annual spring rise of the river was beginning. Several levees broke and the consequent flooding put the uncompleted Arkansas almost four miles (6.4 km) from shore. To further complicate things, the barge that had accompanied the ship from Memphis also sank during this time, and vital machinery and material had to be recovered from the river bottom using a diving bell. Progress on the ironclad advanced at a snail's pace during these difficulties.[25]

On May 19, Beauregard inquired about Arkansas's status and, displeased by the lack of progress, telegraphed Mallory, requesting new leadership for the ironclad. Three days later Mallory appointed Lieutenant Isaac N. Brown captain of Arkansas, ordering him to complete her "without regard to the expenditure of men or money."[26] Mallory ordered McBlair back to Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital, on the 24th. Brown received his orders on 26 May and reached Greenwood three days later. He was disappointed to find the ship much less advanced than he had hoped and found only five carpenters at work and one blacksmith's forge in use. Dismayed by his predecessor's lack of energy and failure to discipline his workforce, Brown requested some workmen from local Confederate Army units and persuaded several local men to join the crew and slave owners to loan some of their slaves to work on the ship that same day. Brown had Arkansas towed back to Yazoo City lest she run aground as the flooding subsided and to utilize the greater resources and manpower available there. He jailed some of the troublemakers among the workmen to reestablish discipline and ordered McBlair off the ship at gunpoint, tired of the senior man's interference.[27]

Brown's appeal for more workers at Yazoo City drew a larger response than he had anticipated, with men volunteering to work on the ship and slave owners volunteering both their field hands and skilled workmen. Brown took advantage of the additional labor by working his men around the clock, every day of the week. Blacksmithing tools were borrowed from local plantation owners and 14 forges were operated at the site to make iron fixtures and machinery parts. With the armor-drilling machinery lost when the barge sank, a makeshift crane was set up on Capitol to hold the newly fabricated drill which was powered by a leather belt driven by the steamboat's hoisting engine.[28] Within five weeks, Arkansas had been mostly completed, although the iron plating on her stern and pilothouse was not yet finished. However, river levels were falling, and further construction was no longer practical. Boiler plate was added to the stern, which was viewed to be less likely to be exposed to enemy fire.[29] Brown described the additional boiler plate as being "for appearance's sake".[4]

The ironclad departed for Liverpool Landing, Mississippi, on either June 22 or 23, to rendezvous with Confederate forces defending the Yazoo River further downstream. A log raft had been constructed there across the Yazoo to serve as a barricade, and three Confederate gunboats were positioned to defend it. While she reached a top speed of eight miles per hour, the voyage revealed the ventilation for the engine room and casemate was grossly inadequate, especially since the boilers were uninsulated. The mechanical weakness of her engines was also demonstrated as they tended to hang up at top dead center, forcing the crew to use pry bars to manually move the pistons to another position to restart the engine. The engines were linked by a 'stopper' that was supposed to stop one engine if the other stopped for any reason, but this never worked and Arkansas would start to turn in a circle as the working engine overpowered the turning force provided by the rudder.[30]

Career

Action on the Yazoo

By this time, a Union Navy fleet commanded by Flag Officer Charles H. Davis, had captured Memphis and occupied the Mississippi River north of Vicksburg, Mississippi, threatening the city.[31] Two unarmed Union ships approached Liverpool Landing on 26 June, causing Commander Robert Pinckney to order his gunboats burned. The Union ships returned to the Mississippi River and Arkansas arrived at the scene after they had left. Brown ordered his crew to try to put out the flames, but they were unsuccessful. Although nothing could be salvaged from the gunboats, quantities of supplies and material, including cannon, had been off-loaded earlier.[32] Two days later Commodore David G. Farragut passed the defenses of Vicksburg to unite with Davis' ships north of the city.[33]

Brown briefly returned to Yazoo City to test his engines, but otherwise remained at Liverpool Landing trying to fix the engines, finishing outfitting the ironclad, and integrating the crews of the destroyed gunboats into his own crew. As his ship became more combat worthy, Brown sent Lieutenant Charles Read to Vicksburg on July 8 to find out what the Confederate commander of the area, Major General Earl Van Dorn, wanted him to do and to scout out the Union fleet between him and the city. Van Dorn ordered him to sortie into the Mississippi to attack the Union ships north of the city and then to proceed south of Vicksburg and destroy the mortar boats there if the condition of his ship allowed him to do so. Around 11 July[34] 60 Missouri artillerymen[35] who had volunteered to serve aboard Arkansas en route to Vicksburg arrived and were given a crash course in operating heavy artillery.[36]

A passage was cut through the raft barrier at Liverpool Landing on July 12, and Arkansas continued downriver to Satartia, Mississippi, accompanied by the tugboat CSS St. Mary. Brown spent all day there on the 13th, exercising his gun crews. Problems occurred on July 14, when the gunpowder in the forward magazine was discovered to have been dampened by steam escaping from her engines. Arkansas had to stop at the riverbank for her crew to allow the powder to dry in the sun. Brown reloaded the dry powder later that day and continued to Haynes Bluff, where he anchored about midnight, intending to surprised the Union ships in the Mississippi at dawn.[37]

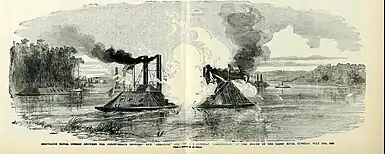

Farragut had been alerted by Confederate deserters that Arkansas was on the Yazoo, although the latest Union intelligence was that she was still incomplete and upriver from Liverpool Landing. Nonetheless, Farragut and Davis agreed to send a reconnaissance mission up the Yazoo to search for the ironclad,[38] consisting of the timberclad gunboat Tyler, the ram Queen of the West, and the ironclad Carondelet.[39] Leaving St. Mary behind, Brown departed his anchorage about 03:00 and spotted the Union ships about three hours later a few miles from the mouth of the Yazoo. Brown ordered his pilots to steer for the Carondelet, intending to ram the Union ship, about two miles (3.2 km) astern of Tyler and Queen of the West. He only authorized his forward guns to fire if they bore directly on a target as he did not want to be slowed down by the cannons' recoil. Tyler drew the first blood of the engagement when a Confederate soldier was decapitated by a projectile while leaning out of a gun port. The two unarmored ships reversed course to fall back on Carondelet, but Arkansas was able to close within a range of 150–200 yards (140–180 m) from Tyler. A shell from one of her Columbiads detonated inside Tyler's engine room, killing 9 men and wounding 16, but the gun recoiled off its mount and it took 10 minutes of hard labor to remount the gun. Although Queen of the West was not armed, she attempted to maneuver into a position from which she could ram the Confederate ship, but was dissuaded by a broadside from Arkansas, and turned downstream.[40]

Tyler followed shortly afterward, continuing to engage the ironclad with her single 30-pounder Parrott rifle stern chaser from a range of 200–300 yards (180–270 m). As Carondelet and Arkansas closed the range, the former's shells bounced off the Confederate ship's armor while the latter's shells began to penetrate the Union ironclad's thinner frontal armor. Commander Henry A. Walke, Carondelet's captain, then ordered his ship to reverse course so that the Arkansas could not ram him, even though the maneuver exposed his unarmored stern with its pair of 32-pounder smoothbore stern chasers. Arkansas was able to close within 50 yards (46 m) of the retreating Union ironclad, but could not get any closer. Within a half hour after the start of the battle, Carondelet's armor had been pierced by at least eight 64-pounder shells, although one of Tyler's shots had struck her pilothouse, wounding both pilots familiar with the Yazoo river. Around this time the sharpshooters aboard Tyler opened fire, shooting at Arkansas's smokestack, gun ports and Brown himself, who had been commanding his ship from the top of the casemate. One Minié ball grazed his head as he was about to descend into the casemate,[41] but only temporarily knocked him unconscious.[42] Arkansas's fire had cut Carondelet's steering ropes and she ran aground in a bend of the river. Brown ordered a broadside fired into the Union ship as Arkansas passed by at point-blank range, intent on reaching the Mississippi.[43] By this time Arkansas's smokestack had been riddled with holes by Union fire and the weakened draft for the boilers had gradually reduced their efficiency and the ship's speed during the battle,[44] so much so that she was only capable of about 3 miles per hour (4.8 km/h) with the current. Other damage to her steam piping and the connection between the funnel and the boilers raised the temperature in her fire room up to 130 °F (54 °C) and 120 °F (49 °C) in the casemate as a result.

The July 15 battle between the ironclads caused heavy damage to the Carondelet and inflicted 35 casualties.[45] About 25 of the Arkansas crew had been killed or wounded during the battle.[46]

To Vicksburg

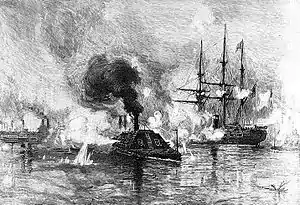

In order to reach Vicksburg, Arkansas needed to force her way through the Union fleet. The crews of Farragut's and Davis' ships had thought that the sound of the guns firing up the Yazoo were from a land engagement and the Queen of the West's captain failed to alert the fleet upon his return. The Confederates had made some repairs to the boiler exhausts and Arkansas able to generate a moderate head of steam by burning oily material by the time she pursued Tyler into the Mississippi at 08:30. Only the ironclad Benton had her boilers lit as there was a shortage of coal at that time, but the continued gunfire between Arkansas and Tyler caused the Union ships prepare for action by attempting to raise steam and manning their guns. For his part Brown initially decided to close all his gun ports[47] and to keep his ship close to the Federal vessels, in order to prevent Union rams from getting much momentum on any ramming attack.[4] The gunboat Pinola opened the fight which prompted Brown to return fire, badly damaging the Union ship. Arkansas was continuously fired upon from all directions with all of her guns replying as they saw targets at a range of about 75 yards (69 m). Brown remained on the casemate roof as his ship approached Farragut's largest ships, the wooden sloops Richmond and Hartford.[48] Before the Arkansas could reach them, the ram Lancaster passed by the ironclad in an attempt to ram her, but was disabled by a shot through the steam drum.[1] Her exact casualties are unknown, but the Union ship was hit many times by friendly fire as she maneuvered into position.[49]

The clouds of smoke produced by all the shooting greatly reduced visibility and the Union ships were additionally handicapped by the presence of Union transports and hospital ships on the other side of the river that might be damaged if they missed Arkansas. Hartford had to wait until the ironclad moved further downstream before she could open fire and was only able to fire a single volley before her guns could no longer bear. One of her shots penetrated the Confederate ship's casemate and killed four men and wounded another. Another shot by the sloop Iroquois killed or wounded the entire 16-man crew of one of the Columbiads and started a small fire that was quickly extinguished. One shot by either the gunboat Wissahickon or her sister Winona penetrated the casemate near a Dahlgren gun, killing three men and wounding three others, travelled through the boiler exhaust to strike the far side of the casemate, killing or injuring 15 men at another gun. By this time the ironclad had little steam available and was mostly drifting with the current. Temperatures in the fire room required the crewmen to be rotated every fifteen minutes so they would not be overcome by heat exhaustion. Brown had thus far spent the entire battle either in the pilothouse or on the casemate's roof and he returned to the latter position to seek relief from the heat. Despite his exposed position, he was only slightly wounded during the battle.[50]

The improved visibility atop the casemate allowed him to see that the only remaining ships that he had to pass were a few of Davis' ironclads, although only two were combat worthy at that time. Benton had steam up and was able to move slowly as Arkansas approached, slowly enough that Brown attempted to ram her. The Union ironclad was able to speed up enough to evade the Confederate ship, although she was lightly damaged when the Arkansas fired a broadside into Benton's stern as she passed by. The ironclad Cincinnati was the last ship barring the way to Vicksburg, but she barely had any speed up and was easily evaded. The two Union ironclads pursued the Arkansas until a brief gun duel with the city's defenses caused them to head back upstream. The mortar boats below the city were warned that the ironclad was passing through the Union fleet and they temporarily withdrew downstream, during which time the schooner Sidney C. Jones ran hard aground and was burned to prevent her capture. The Confederate ship had fired 97 shots during the day, only 24 of which had missed a Union ship.[51]

Arkansas received an enthusiastic welcome at Vicksburg. A crowd formed at the wharf where the ship docked, and Van Dorn embraced Brown. However, several spectators observed the gory carnage within the ironclad and were unnerved. Thirty men had been killed or wounded on the vessel.[52] Brown and his crew spent the rest of the day taking care of the dead and wounded, replenishing the ship's supply of coal and making temporary repairs. An unknown number of volunteers from the city's garrison were received to at least partially replace the day's losses. During this time, the ironclad was ineffectually fired upon by the mortar boats and Union artillery and infantry units across the river.[53] Farragut decided to run his fleet past the Vicksburg batteries and destroy Arkansas that evening. He had originally planned for the movement to begin at 16:00, but a storm came up, delaying the advance until 21:00. By then, it was getting dark. The Arkansas was rust-colored and was docked against a red riverbank, which made her much less visible and significantly degraded the accuracy of the Union guns.[1] The fire from Farragut's ships was generally ineffectual, although a shot from the sloop USS Oneida destroyed Arkansas's sickbay, damaged her machinery and killed three crewmen and wounded three others. While the effect of the ironclad's fire upon the Union ships is generally unknown, the shot that disabled the gunboat Winona's engines is attributed to the Arkansas.[54] While Farragut's fleet made it downriver past Vicksburg, it had been unsuccessful in destroying its target and the Confederate guns were similarly ineffective.[4] The Union fleet had suffered 92 casualties during the day's actions.[55]

The next day, July 16, saw Union ships begin firing at Arkansas with mortars, necessitating the frequent moving of the ship to keep the Union ships from getting the ironclad's range. The Missourians had only joined the ship's crew for duration of the run to Vicksburg, and returned to their commands on July 16.[56] This left Arkansas with a serious crew shortage.[1] Brown had permission from Van Dorn to recruit men from Vicksburg's army garrison, but getting volunteers to serve on the ship was difficult due to the off putting effect of the damage from the ship's fight with the Union fleet.[56]

Under the Vicksburg bluffs

Three days after the fight, Arkansas had been repaired to a more mobile position again, and began posing a threat to the Union fleets, which were forced to keep steam pressure up so they could move if need be. At one point, the vessel attempted to threaten the Union's mortar ships, but its engines failed before it entered range of the Union position; Arkansas returned to its starting position.[57] The reduced crew still caused problems, as there were only enough men onboard to man three cannons at a time.[4] After a conversation, Farragut and Davis decided to attack Arkansas at her position at Vicksburg.[58] The attack fell on July 22, and was conducted by Essex, Queen of the West, and Sumter.[4] Essex was the largest ironclad the Union had available, and Queen of the West was the strongest ram.[58]

Arkansas was not prepared for a battle. The ship's engine was disabled, and the understrength crew was reduced even further with a number of men in hospitals at the time. Brown had only part of his officer corps and 28 crewmen present; only two cannons could be manned with the available crew.[58] The Union vessels did not coordinate well. Essex tried to ram Arkansas, but the Confederate vessel maneuvered out of the way, while its opponent missed and temporarily ran aground.[4] A close-range duel between the two ships followed, in which Essex suffered little damage, but a shot penetrated Arkansas, inflicting casualties.[1][lower-alpha 2] That single shot also damaged Arkansas's superstructure. Queen of the West rammed the Confederate vessel, but caused no major damage; it also ran aground. Once the two Union ships freed themselves, Essex continued downriver from Vicksburg, while Queen of the West returned to the north of the city.[58] A parting shot from Arkansas hit Queen of the West in the stern during the retreat; the shot had skipped off the water several times before striking the ship.[60]

After the attack against Arkansas, Farragut decided that remaining in position near Vicksburg was no longer tenable. The expected seasonal drop in river level threatened to strand his ships on the Mississippi, a third of his sailors were sick, and the Navy was unlikely to receive needed help from the Army. The threat caused by the presence of Arkansas did not help the matter.[4] On July 23, orders from United States Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles permitted Farragut to abandon the position and leave for the Gulf of Mexico. The next day, Farragut's ships began the movement downriver, leaving Davis behind to continue bombarding the Confederates. However, Davis, on his own initiative, ordered a withdrawal to Helena, Arkansas, on July 28. His crews had been decimated by disease, and he risked not having enough men to continue to operate his ships if he did not withdraw.[61]

Final fight at Baton Rouge

With the threat of the Union fleets no longer present, Brown was granted four days of leave at Grenada, Mississippi, for recovery from injuries. Before leaving, he ordered Lieutenant Henry K. Stevens that Arkansas should not be moved. Van Dorn was also informed that the ship's engine problems prevented her from being usable without repairs.[4] Brown fell ill, while Van Dorn planned an attack on the Union-held city of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Major General John C. Breckinridge was in charge of the Confederate army assault against Baton Rouge, but soon saw almost half of his force stricken by disease. To make up for the loss in manpower, Breckinridge asked for Arkansas to support his attack. Despite the ship still being in a poor state of repair, Van Dorn ordered her to take part in the attack.[1] Stevens objected, citing Brown's orders that the ship should not be moved, and the question went to the Confederate States Department of the Navy, who decided not to intervene. After making final preparations, Stevens was forced to steam the ironclad towards Baton Rouge.[4] Brown learned of the debate, and left his sickbed to prevent Arkansas from leaving Vicksburg, but learned that she had already left when he reached Jackson.[1]

Complicating matters, the ship's regular engineer was too sick to make the journey, and an army volunteer who lacked experience with the type of engines used on the ship served as the engineer.[62] Engine troubles occurred during the journey, causing the ship to spin.[1] Essex was one of the Union ships at Baton Rouge, and her fire helped repulse Breckinridge's attack in the Battle of Baton Rouge. After reaching a point close enough to see Baton Rouge, Stevens and the ship's pilot decided upon a plan of attack: to ram and sink Essex and then move downstream in order to block the retreat of the smaller Union vessels present.[63] During the movement, Arkansas suffered another engine failure, which caused her to run aground on some cypress stumps. It took several hours to repair the engines, and some iron that had been covering the deck was thrown overboard to lighten the ship.[64] Arkansas was able to free herself, but the strain on the engines caused a crank pin to break. A forge was constructed to create a new pin,[1] and an engineer on board the ship with blacksmithing experience created a new one.[64] Fixing the engine took all night, and when the ship attempted to move downstream again on August 6, the other engine broke down, rendering her immobile. Essex approached, and Stevens ordered the scuttling of his ship.[1][4] Burning, Arkansas floated downstream before blowing up and sinking around noon.[4]

In 1981, the National Underwater and Marine Agency discovered the wreck of Arkansas under a levee below Free Negro Point, near Mile 233. The site is possibly the location of an old sand and gravel pumping site that reported finding skeletons and projectiles.[65]

Notes

- ↑ The exact nature of the cannons varies between sources. After the war Lieutenant George W. Gift, commander of the forward guns, stated that the weapons were two 8-inch Columbiads, a pair of 9-inch Dahlgren guns, an 8-inch "shell gun", a 32-pounder smoothbore gun, and four rifled 32 pounders. Commander Isaac Brown, the ship's captain, enumerated them as two 8-inch 64-pounders, two rifled 32-pounders, four 100-pounder Columbiads, and two 6-inch (152 mm) rifled guns.[12] Lieutenant Charles Read, commander of the ship's aft guns wrote that the ship was armed with two Columbiads, two Dahlgrens, four rifled and two smoothbore 32 pounders. Gift's assistant, Master's Mate John Wilson, matched Read's recollection in his contemporaneous diary.[13]

- ↑ The number of casualties caused by this single shot varies among sources. Donald Barnhart, writing for the Civil War Times Illustrated, stated that seven men were killed by the shot.[1] The Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships says six were killed and six wounded,[4] while Donald L. Miller gives a total figure of 14 casualties.[58] George W. Gift, one of the ship's officers, wrote that seven men were killed and six wounded.[59]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Barnhart

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 33–36.

- ↑ Smith 2011, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Marcello 2016.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 34–35, 42–43.

- 1 2 3 Silverstone 2006, p. 150.

- ↑ Bisbee 2018, p. 70.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 52, 69.

- ↑ Bisbee 2018, pp. 70–73.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 52, 54, 101–102.

- ↑ Gosnell 1949, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Smith 2011, p. 97.

- ↑ Smith 2011, p. 52.

- ↑ Holcombe 1997, p. 53.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 42, 52, 59–60, 97–100, 103.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 47, 53, 57.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 62–64, 67, 69.

- ↑ Smith 2011, p. 71.

- ↑ Canney 2015, p. 27.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 71, 74.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 74.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 75, 78–79.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 80–82.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 86–87, 89–92.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 95–99.

- ↑ Gosnell 1949, pp. 103–105.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 120, 122–123.

- ↑ Chatelain 2020, p. 132.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 127–129.

- ↑ Chatelain 2020, pp. 183–184.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 135, 137–138.

- ↑ McGhee 2008, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Smith 2011, p. 138.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 140–145.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 145–146.

- ↑ Miller 2019, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 145, 155–160.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 160–164.

- ↑ Miller 2019, p. 159.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 165–168.

- ↑ Miller 2019, p. 160.

- ↑ Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History Division. 1963.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 175–176, 178.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 178–183.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 183–185.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 185–186.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 186, 190–195.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 195–200.

- ↑ Miller 2019, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 210–215.

- ↑ Smith 2011, pp. 222–223, 226–227.

- ↑ Spurgeon, John (26 February 2013). "CSS Arkansas". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- 1 2 Gosnell 1949, p. 126.

- ↑ Gosnell 1949, pp. 127–128.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Miller 2019, p. 162.

- ↑ Gosnell 1949, p. 129.

- ↑ Gosnell 1949, p. 130.

- ↑ Miller 2019, pp. 163–164.

- ↑ Gosnell 1949, p. 132.

- ↑ Gosnell 1949, p. 133.

- 1 2 Gosnell 1949, p. 134.

- ↑ "Search for the Ironclads". National Underwater and Marine Agency. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

Sources

- Barnhart, Donald J. (May 2001). "Junkyard Ironclad". The Civil War Times Illustrated. 40 (2). ISSN 0009-8094.

- Bisbee, Saxon T. (2018). Engines of Rebellion: Confederate Ironclads and Steam Engineering in the American Civil War. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-81731-986-1.

- Canney, Donald L. (2015). The Confederate Steam Navy 1861–1865. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-4824-2.

- Chatelain, Neil P. (2020). Defending the Arteries of Rebellion: Confederate Naval Operations in the Mississippi River Valley, 1861–1865. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-510-6.

- Gosnell, H. Allen (1949). Guns on the Western Waters. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 27132761.

- Holcombe, Robert (1997). "Types of Ships". In Still, William N. Jr. (ed.). The Confederate Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization, 1861–1865. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 40–68. ISBN 0-85177-686-8.

- McGhee, James E. (2008). Guide to Missouri Confederate Regiments, 1861–1865. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 978-1-55728-870-7.

- Marcello, Paul J. (2 March 2016). "Arkansas (Ironclad Ram)". Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- Miller, Donald L. (2019). Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4139-4.

- Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I: 27 volumes. Series II: 3 volumes. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922. See particularly Series I, volume 19, pp. 3–75.

- "Search for the Ironclads: The Expedition to Find the Confederate Ironclads Manassas, Louisiana, and Arkansas". National Underwater and Marine Agency. November 1981. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (2006). Civil War Navies 1855–1883. The U.S. Navy Warship Series. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97870-X.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Smith, Myron J. (2011). The CSS Arkansas: A Confederate Ironclad on Western Waters. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4726-8.

- Still, William N. Jr. (1985) [1971]. Iron Afloat: The Story of the Confederate Armorclads. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-454-3.

Further reading

- Parker, William Harwar (1899). "Chapter VIII: The Ram Arkansas – Her Completion on the Yazoo River – Her Daring Dash Through the Federal Fleet". In Evans, Clement A. (ed.). The Confederate States Navy. Confederate Military History. Vol. XII. Atlanta, Ga.: Confederate Publishing Company. pp. 63–66 – via Internet Archive.

External links

- CSS Arkansas (Vicksburg, Mississippi) at the Historical Marker Database

- CSS Arkansas (Yazoo City, Mississippi) at the Historical Marker Database

- Missourians or Volunteers From Missouri Units on the CSS Arkansas at Internet Archive