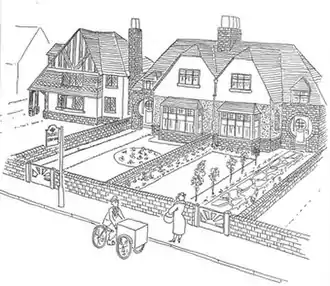

By-pass Variegated is a term coined by the cartoonist and architectural historian Osbert Lancaster in his 1938 book Pillar to Post. It represents the ribbon development of houses in Britain in the 1920s and 1930s, in a mish-mash of architectural styles.

Style

Before 1947 there was no systematic legal control of property development in Britain: landowners could in general build as they wished on their land.[1] Between the First and Second World Wars speculative builders bought large tracts of land alongside new arterial roads and built mile after mile of mostly semi-detached, and some detached, houses. They were built as cheaply as possible, allowing people with modest incomes to buy a home for the first time, rather than rent. In the inter-war period owner-occupation in Britain rose from 10 to 32 per cent.[2] In a 2010 study of Britain in the 1930s, Juliet Gardiner gives an example of a working-class couple buying a new house of this kind in Hornchurch, Essex for £495.[3]

In Lancaster's view, houses in the "By-pass Variegated" style were badly designed from both the practical and the aesthetic point of view, combining "the maximum of inconvenience" of layout with an incongruous mixture of old styles jumbled together in the façades, combining features copied from Art Nouveau, Modernism, Stockbroker's Tudor, Pont Street Dutch, Romanesque and other styles.[4] He added that the historical details were "in almost every case the worst features of the style from which they were filched".[4]

In addition to the internal inconveniences and the external aesthetic considerations, Lancaster remarked on "the skill with which the houses are disposed that insures that the largest possible area of countryside is ruined with the minimum of expense".[4] He also criticised the typical layout that gave each householder "a clear view into the most private offices of his next-door neighbour" and a disregard for natural light in the construction of the principal rooms.[4]

Like several other coinages in Pillar to Post, "By-pass Variegated" has been taken up by later writers. It appears in the journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects;[5] The Guardian used it in its 2015 survey A History of Cities in 50 Buildings.[6] In the London Review of Books, Rosemary Hill ranks the term with "Stockbroker's Tudor" as having passed into the language.[7] In The New Statesman, Stephen Calloway included "By-pass Variegated" in Lancaster's "pin-point-sharp litany of names still widely used today", along with Kensington Italianate, Municipal Gothic, Pont Street Dutch, Wimbledon Transitional, Pseudish and Stockbrokers' Tudor.[8] The term has been translated into German as "Stadtumgehungsstil".[9]

References and sources

References

- ↑ Tavernor, Robert. "Architectural conservation", The New Oxford Companion to Law, Oxford University Press, 2008. Retrieved 7 May 2012 (subscription required)

- ↑ Scott, pp. 4–5

- ↑ Gardiner, p. 304

- 1 2 3 4 Lancaster, p. 86

- ↑ "Keeping Perspective", RIBA Journal, 21 September 2015

- ↑ Wainright, Oliver. "The grand London 'semi' that spawned a housing revolution", The Guardian, 1 April 2015

- ↑ Hill, Rosemary. "Bypass variegated", London Review of Books, 21 January 2016

- ↑ Calloway, Stephen. "A talent to amuse: Cartoons and Coronets: the Genius of Osbert Lancaster", The New Statesman, 23 October 2008

- ↑ Yapp, p. 206

Sources

- Gardiner, Juliet (2010). Sitting on a Jigsaw: Britain in the Thirties. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-731453-9.

- Lancaster, Osbert (1938). Pillar to Post: The Pocket Lamp of Architecture. London: John Murray. OCLC 1150976101.

- Scott, Peter (2004). Visible and Invisible Walls: Suburbanisation and the social filtering of working-class communities in interwar Britain (PDF) (Thesis). University of Reading. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- Yapp, Nick (1999). London: Geheimnisse und Glanz einer Weltstadt (in German). Köln: Könemann. ISBN 978-3-82-900483-1.