British logistics played a key role in the success of Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of France in June 1944. The objective of the campaign was to secure a lodgement on the mainland of Europe for further operations. The Allies had to land sufficient forces to overcome the initial opposition and build them up faster than the Germans could respond. Planning for this operation had begun in 1942. The Anglo-Canadian force, the 21st Army Group, consisted of the British Second Army and Canadian First Army. Between them, they had six armoured divisions (including the Polish 1st Armoured Division), ten infantry divisions, two airborne divisions, nine independent armoured brigades and two commando brigades. Logistical units included six supply unit headquarters, 25 Base Supply Depots (BSDs), 83 Detail Issue Depots (DIDs), 25 field bakeries, 14 field butcheries and 18 port detachments. The army group was supported over the beaches and through the Mulberry artificial port specially constructed for the purpose.

During the first seven weeks after the British and Canadian landings in Normandy on D-Day, 6 June 1944, the advance was much slower than anticipated, and the lodgement area was much smaller. The short lines of communication provided an opportunity to accumulate reserves of supplies. Two army roadheads were created. No. 1 Army Roadhead for I Corps and No. 2 Army Roadhead for XXX Corps, these being the two corps ashore at the time. When the Canadian First Army assumed control of the British I Corps on 21 June, the No. 1 Army Roadhead also passed into its control. No. 2 Army Roadhead formed the nucleus of what became the Rear Maintenance Area (RMA) of the 21st Army Group. By 26 July, 675,000 personnel, 150,000 vehicles and 690,000 tonnes (680,000 long tons) of stores and 69,000 tonnes (68,000 long tons) of bulk petrol had been landed. Ammunition usage was high, exceeding the daily allocation for the 25-pounder field guns by 8 per cent and for the 5.5-inch medium guns by 24 per cent. Greater priority was given to ammunition shipments, with petrol, oil and lubricant (POL) shipments cut to compensate.

On 25 July, the US First Army began Operation Cobra, the break-out from Normandy. On 26 August, the 21st Army Group issued orders for an advance to the north to capture Antwerp, Belgium. After a rapid advance, the British Guards Armoured Division liberated Brussels, the Belgian capital, on 3 September and the 11th Armoured Division captured Antwerp the following day. The advance was much faster than expected and the rapid increase in the length of the line of communications threw up logistical challenges that, together with increased German resistance, threatened to stall the Allied armies. By mid-September, the Allies had liberated most of France and Belgium. The success of the 21st Army Group was in large part due to its logistics, which provided the operational commanders with enormous capacity and tremendous flexibility.

Background

Between the world wars the British Army developed a doctrine based on using machinery as a substitute for manpower. In this way, it was hoped that mobility could be restored to the battlefield and the enormous casualties of the Great War could be avoided.[1] The Army embraced motor transport and mechanisation as a means of increasing the tempo of operations. The wholesale mechanisation of the infantry and artillery was ordered in 1934 and by 1938, the British Army had only 5,200 horses, compared with 28,700 on the eve of the Great War in 1914. In the Second World War, the Army relied entirely on motor transport to move supplies between the railheads and the divisional depots.[2]

France was occupied by Germany in June 1940 following the German victory in the Battle of France. An important factor in the defeat was the failure of the logistical system of the British Expeditionary Force, which responded too slowly to the rapid German advance.[3] In the aftermath, the prospect of a British army invading and liberating France was remote, and the British Army concentrated on repelling rather than mounting a cross-channel attack. On 19 June 1940, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), General Sir John Dill, ordered that all line of communications units not required for home defence be disbanded and no further units be raised. In the event of an invasion of the UK, the Home Forces planned to rely on civilian resources for transportation, communications and maintenance. In March 1941, the War Cabinet decided that the Army had reached its maximum size. Henceforth, although the manpower "ceiling" was to be raised a little, this meant that raising more logistical units required the conversion of other units.[4]

By this time, Home Forces divisions had a divisional slice (the personnel of the division plus the supporting operational and logistical units at corps and army level) of 25,000, but overseas operations required one of 36,500 to 39,000.[4] The German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 drew German forces away from the west, and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, while having the immediate effect of diverting troops from the war against Germany, brought the United States into the war, with the prospect of substantial resources over the longer term. This made realistic planning for an invasion of France possible.[5] A War Office staff study in May 1942 for Operation Sledgehammer, an assault on France in 1942, revealed that an expeditionary force of six divisions would require all the logistical units in the UK, but not until 18 December 1942 was a final decision taken that a German invasion of the UK in 1943 was highly unlikely, and the reorganisation of the forces in the UK for an invasion of France could begin.[6]

Operation Sledgehammer was superseded by Operation Roundup, a plan for an invasion of France in 1943. In January 1943, the Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces, General Sir Bernard Paget, estimated that an expeditionary force of eleven British and five Canadian divisions could be assembled by August 1943, but the diversion of resources to the Mediterranean theatre meant that by August there were only enough logistical units to support five divisions, and the full force would not be assembled until April 1944. By November 1943, the force earmarked for France had dropped to twelve British and Canadian divisions, but the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, felt that as the Americans were contributing fifteen divisions, this should be matched. Three divisions were therefore withdrawn from the Mediterranean.[7]

The British Army's administrative doctrine was honed in the Western Desert Campaign, where lessons were learnt and administrative staff and logistical units developed effective procedures through trial and error.[8] Doctrine based on fighting in Europe where there was a temperate climate and well-developed road and rail infrastructure was set aside and new organisational and logistical structures such as the Field Maintenance Centre (FMC) were developed.[9] By 1944, the skill of the British Army in the field of logistics had been brought to a high state of efficiency and support from the United States through Lend-Lease made enormous quantities of materiel available.[8] Mechanisation and overwhelming firepower demanded a great deal from the Army's logistical infrastructure. Fortunately, the British Army had 200 years' experience of fighting campaigns far from home.[10]

Planning

A plan for a cross-channel invasion was drawn up by a staff led by the designated chief of staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), and approved at the Quebec Conference in August 1943. It was codenamed Operation Overlord.[5] COSSAC also inherited and developed plans for Operation Rankin, a contingency plan for a sudden German collapse.[11] Home Forces headquarters was divided in two in May 1943 to create an expeditionary headquarters, the 21st Army Group.[12] From January 1944, the army group, consisting of the British Second Army and the Canadian First Army, was commanded by General Bernard Montgomery.[13] The two armies comprised six armoured divisions (including the Polish 1st Armoured Division), ten infantry divisions, two airborne divisions, nine independent armoured brigades and two commando brigades.[14] Although it contained personnel from many nations, the logistical support was British. There was virtually no separate Canadian supply organization other than what existed within First Canadian Army itself. The great majority of Canadian requirements were drawn from British sources.[15]

The total strength of the British and Canadian components of the 21st Army Group was about 849,000, of which 695,000 were British Army, 107,000 were Canadian Army and 47,000 were members of the Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).[16] Of the British troops in the 21st Army Group, 56 per cent were in the combat and combat support arms, artillery, infantry, armour, engineers and signals. The 44 per cent in the services included 15 per cent in the Royal Army Service Corps (RASC), 10 per cent in the Pioneer Corps, 5 per cent in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME), 4 per cent in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), Royal Army Dental Corps and Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) and 10 per cent in other services, such as the Royal Army Ordnance Corps (RAOC) and the Corps of Military Police (CMP).[17]

Logistical units included six supply unit headquarters, 25 Base Supply Depots (BSDs), 83 Detail Issue Depots (DIDs), 25 field bakeries, 14 field butcheries and 18 port detachments. This was less than the planners called for, as fewer logistical units returned from the Mediterranean than anticipated. In April 1944, the RASC, the corps of the British Army responsible for most forms of supply and transport, was about 15,000 men short of its requirements. About 9,000 men were transferred from anti-aircraft units, 1,000 from Home Forces and 1,000 from units in the Middle East. This meant that they were still 4,000 men short at the end of May and this had to be accepted. Units intended for beach work received additional training at Combined Operations training centres. Eleven general transport companies were equipped with DUKWs and were trained at the RASC Amphibious Training Centre at Towyn in Wales.[16]

The United States First Army was also assigned to the 21st Army Group for the assault phase of the campaign and although the United States Army maintained a separate supply organisation, an American brigadier general was assigned as a deputy to the Major-General Administration (MGA) of the 21st Army Group and representatives of the American G-1 and G-4 sections were attached to their opposite numbers at 21st Army Group, the A and Q staffs.[14] The MGA, Major-General Miles Graham, had three principal subordinates: a Deputy Quartermaster General (DQMG) for plans and maintenance, Brigadier Randle (Gerry) Feilden; a DQMG for movements and transportation, Brigadier L. L. H. McKillop; and a Deputy Adjutant General (DAG), Brigadier Cyril Lloyd, responsible for personnel and administrative services.[14][18]

A Headquarters (HQ) Line of Communications was formed from that of the disbanded 54th (East Anglian) Infantry Division. Most of its component areas and sub areas were formed for the campaign.[19] This was commanded by Major-General Frank Naylor, formerly the Vice QMG at the War Office.[20] In the assault, 101 and 102 Beach Sub Areas would support I Corps while 104 Beach Sub Area supported XXX Corps.[21] Each beach sub area controlled two beach groups.[21] These were tri-service formations with units from the Royal Engineers, RAMC, REME, RAOC, RASC, Pioneer Corps and Military Police. The Royal Navy provided each with a Royal Navy Beach Commando and a signal unit; the RAF provided beach anti-aircraft defence. Each beach group also had an infantry battalion to mop up any opposition and then act as a labour force. A beach group had a complement of about 3,000 men.[22] The beach sub-areas would come under 11 Line of Communications Area when Second Army HQ arrived in Normandy and it in turn came under HQ Line of Communications when the 21st Army Group HQ arrived.[23]

Plans called for four days' supply of ammunition, 50 miles (80 km) of fuel for all vehicles and two days' supplies for the troops ashore by D+3 (i.e. three days after D-Day), which would be gradually increased to a fortnight's reserves of all commodities by D+41. At first, casualties would be evacuated to the UK by landing ships or small hospital ships. Once hospitals were established ashore, only casualties requiring more than seven days' treatment would be returned to the UK. This would be increased later as more hospitals were established on the continent. Numbers were forecast based on War Office tables known as Evetts rates, after Major-General John Evetts, the Assistant Chief of the General Staff, who devised them. For planning purposes, it was assumed that casualties on D-Day would be at an exceptionally high ("double intense") rate. In the event, this was not the case.[24] A special feature was the provision of "survivor's kits" at the beach dumps. These were bags packed with a full set of soldier's equipment and clothing, which could be issued to individuals who had lost all their kit through the sinking of their ship or landing craft.[25] Prisoners of war (POWs) were to be evacuated to camps in England.[26]

Two important coordinating bodies were created. The Build-Up Control Organisation (BUCO) was formed on 20 April 1944 at Combined Operations Headquarters (although it was not part of it). It was charged with responsibility for regulating the build-up of vehicles and personnel by allocating priorities for the available shipping. Once the final plans for the landing were drawn up, all further alterations had to be implemented by BUCO. Movement Control (MOVCO) was responsible for the movement of units to the coastal areas and ports from which they would embark. Like BUCO, it had separate staffs for the American and British zones which operated independently. There was also the Turnaround Control Organisation (TURCO), which controlled the turnaround of shipping at the ports of loading; the Combined Operations Repair Organisation (COREP), which handled repairs to damaged ships and landing craft; the Combined Tugboat Organisation (COTUG) managed a fleet of tugboats.[27][28]

The objective of the campaign was to secure a lodgement on the mainland of Europe from which further operations could be conducted. The lodgement area had to be large enough and have sufficient port facilities to maintain between twenty-six and thirty divisions, with additional divisions arriving at the rate of three to five a month. The Allies had to land an assault force sufficient to overcome the initial opposition and build it up faster than the Germans could respond.[29] The campaign plan involved a landing in Normandy, followed by an advance to the south. The ports in Brittany would be captured, and the Allied armies would then turn east and cross the Seine River. For administrative planning purposes, it was assumed that the Breton and Loire ports would be captured by D+40 and the Seine reached by D+90.[30] Montgomery did not expect that the campaign would unfold according to plan and did not commit himself to a timetable. "Whether operations will develop on these lines", he noted on 8 May, "must of course depend on our own and the enemy situation which cannot be predicted accurately at the present moment".[31] The assault had to be postponed for 24 hours but there were contingency plans that covered both this and a 48-hour postponement.[27]

Assault

The landings on D-Day, 6 June, were successful. Some 2,426 landing ships and landing craft were employed by Vice-Admiral Sir Philip Vian's Eastern Naval Task Force in support of the British and Canadian forces, including 37 landing ships, infantry (LSI), 3 landing ships, dock (LSD), 155 landing craft, infantry (LCI), 130 landing ships, tank (LST) and 487 landing craft, tank (LCT).[32] While the fighting was fierce in some places, it was not as severe as had been feared.[33]

The slope of the beaches was not steep; gradients varied from 1:100 to 1:250, with a tidal range of about 6 metres (20 ft). It was difficult for landing craft to discharge motor vehicles at low tide, or to beach during an ebbing tide. This meant that except at high tide, landing craft and LSTs were beached. Causeways were constructed to allow them to discharge. Ships carrying stores had to anchor up to 5 miles (8 km) from shore, resulting in lengthy turnaround times for the DUKWs and other unloading craft.[24][34]

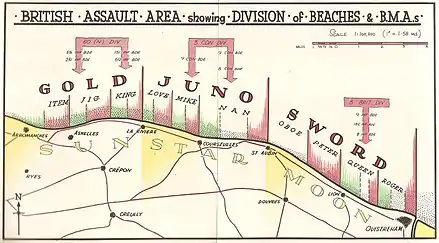

Gold Beach was the objective for 104 Beach Sub Area, landed with the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division. King Beach was supposed to be developed by 9 Beach Group but its peat and soft clay was found to be too soft and was abandoned, except for a pontoon causeway for landing personnel. Landing beaches were divided into red and green landing areas. An LCT landing point was established at Love Green beach. Item Red and Jig Green Beaches were developed by 10 Beach Group, as planned. The main dumps were not ready to receive stores until 8 June, so in the meantime, stores were accumulated in temporary locations near the beach.[35]

The landing of 102 Beach Sub Area with the 3rd Canadian Division on Juno Beach was delayed by rough seas and the development of Mike Beach by 7 Beach Group was delayed by fire from Vaux-sur-Aure. The German stronghold there was eliminated on 8 June by 7 Beach Group, supported by armour. Bad weather delayed the arrival of four coasters from England on D-Day and seven more on 7 June. This was offset when the tiny port of Courseulles-sur-Mer was captured intact on D-Day, allowing 1,000 tonnes (1,000 long tons) per day to be unloaded there, but it proved unsuitable for coasters and was abandoned on 10 June.[35]

At Sword Beach, 101 Beach Sub Area landed with the British 3rd Division, 5 Beach Group with its assault brigade and 6 Beach Group with its follow-up brigade. Four LCTs, each loaded with 200 tonnes (200 long tons) of high-priority stores were beached and rapidly unloaded into temporary dumps near the beaches. These had been intended for use on D-Day only but the intended beach maintenance area had not been captured and was not ready to receive stores until 9 June.[35]

Although it was captured intact on D-Day, the small port of Ouistreham could not be used due to German shellfire from around Caen. There were some attacks by E-boats and a German air raid on 8 June struck the beach maintenance area, destroying 450,000 litres (100,000 imp gal) of petrol and 410 tonnes (400 long tons) of ammunition.[24] Replacements were ordered with a high priority. Due to this interference, 101 Beach Sub Area posted the lowest receipt-of-stores rates; Sword Beach was closed on 12 July.[35] Minesweeping did not commence at Ouistreham until 21 August and it was not opened to shipping until 3 September.[36]

Build-up

Bayeux was captured on 7 June but the lodgement area was smaller than anticipated, with determined German resistance being encountered. Between 16 and 30 June, the British Second Army mounted a series of operations to capture Caen, but it remained in German hands. Finally, after a bombardment by 420 heavy bombers from RAF Bomber Command on 7 July, Caen was taken on 9 July. Operation Goodwood was launched on 18 July and to contain the British and Canadian forces, almost all the German armour was concentrated east of the Orne River, paving the way for a successful advance in the American sector.[33]

Organisation

Corps and divisional administrative staffs landed on D-Day. The Second Army staffs began landing the following day, allowing it to assume administrative control on 11 June, but the restricted lodgement area made the corps headquarters reluctant to relinquish control of the depots and dumps around the beaches. The beach sub area commanders found themselves answerable to corps, army and when it arrived, 11 Line of Communications Area. On 14 June, with the lodgement area 8 to 12 miles (13 to 19 km) deep with a front 50-mile (80 km) long, Second Army assumed command of the beach sub areas, marking the end of the assault phase of Overlord.[37]

Two army roadheads were created: No. 1 Army Roadhead for I Corps, and No. 2 Army Roadhead for XXX Corps. When the Canadian First Army assumed control of the British I Corps on 21 June, No. 1 Army Roadhead also passed to its control.[38] Henceforth odd numbered roadheads served the Canadian First Army and even numbered ones the British Second Army.[39] No. 2 Army Roadhead formed the nucleus of what became the Rear Maintenance Area (RMA) of the 21st Army Group.[38] At the RMA, there was a Commander, RASC (CRASC) Supply units, who had eight BSDs, eight DIDs, 13 field bakeries and two field butcheries. There was also a CRASC Petrol Installation, whose command included 28 petrol depots and twelve mobile petrol filling centres (MPFCs).[40] Each MPFC could refill up to 8,000 jerry cans per day.[41]

On 15 June, 151 Forward Maintenance Area was opened by XXX Corps. The FMA concept, which had been used with success in the Mediterranean theatre, was not part of British doctrine. Unlike divisions, which incorporated logistics units, a corps was a purely operational formation and not part of the logistical plan. Doctrine called for the use of pack trains, railway trains which would deliver days' supplies direct to a division. These had worked well in the Great War but had been found to be impractical in the Middle East and were never seriously considered for Overlord.[38] The FMA was only a few miles from No. 2 Army Roadhead but the XXX Corps staff considered that it knew best, given its combat experience in the North African Campaign and the Allied invasion of Sicily. The other corps of Second Army followed suit and established their own FMAs. Under the FMA scheme, divisions drew maintenance from the FMA rather than the roadhead.[38]

The FMA allowed a corps to train newly arrived administrative units, to control the usage of ammunition by the divisions and alleviate the traffic congestion around Bayeux. The British Second Army gave tacit support for the practice, issuing an order that FMAs be called Field Maintenance Centres (FMCs), the original nomenclature in the Mediterranean. Henceforth, Second Army stocked the army roadhead and left the FMCs to the corps. The FMCs were manned using corps resources; each had two DIDs, a petrol depot, a transport company and two RASC composite platoons drawn from corps troops composite companies. Where possible, an MPFC was attached to each FMC. Occasionally they had to be reinforced with some additional transport platoons from Second Army. This organisation allowed an FMC to be operated while another was established. Each FMC held two days' rations and one day's maintenance stocks, two or three days' petrol, which was about 910,000 litres (200,000 imp gal) and 3,600 tonnes (3,500 long tons) of ammunition. Corps services such as the reinforcement centre, salvage unit, tank delivery squadron and ordnance field park tended to cluster around the FMC.[38][42]

By 26 July, 675,000 personnel, 150,000 vehicles, 690,000 tonnes (680,000 long tons) of stores and 69,000 tonnes (68,000 long tons) of bulk petrol had been landed. There was 23 days' reserves of stores and 16 days' reserves of petrol, with a day's supply of petrol being taken as enough to drive every vehicle 30 miles (48 km).[43] Confronted by German defences in depth, the British forces relied on air and artillery firepower. Any German artillery battery, once detected, could expect 20 long tons (20 t) of shells on average.[44] Ammunition reserves varied from five days' supply for the 5.5-inch medium guns to 30 days' supply for the 17-pounder anti-tank guns. Usage exceeded the seventy rounds per gun per day allocation for the 25-pounder guns by six rounds per gun per day and the allocation of fifty rounds per gun per day for the 5.5-inch guns by twelve per gun per day. Fears that the crowded lodgement area would prove a tempting target for the Luftwaffe led to an overstock of anti-aircraft ammunition. Later shipments of anti-aircraft ammunition were cancelled and other types of artillery ammunition were substituted. The requirement for tank and anti-tank ammunition was also over-estimated.[45] While it seemed to the Germans that the British Army had an unlimited supply of ammunition, this was not the case and a reason why heavy bombers were used to augment the artillery in Operation Goodwood.[46]

Mulberry harbour

No major ports were expected to be captured in the early stages of Overlord except Cherbourg. The capture was expected to take three weeks and the port was not large enough to meet the Allied needs. Until a major port could be captured, maintenance would have to be over open beaches that were at the mercy of the weather. Two artificial Mulberry harbours were planned: Mulberry A for the American sector and Mulberry B for the British sector. Work commenced in 1942 and prototypes were tested in 1943. Mulberry A was to have a capacity of 5,100 tonnes (5,000 long tons) per day and Mulberry B of 7,100 tonnes (7,000 long tons). Each would handle 1,200 vehicles daily, and provide shelter for small craft.[47]

Mulberry breakwaters consisted of blockships, concrete caissons known as Phoenix breakwaters and floating breakwaters known as Bombardon breakwaters. Their construction consumed tens of thousands of tons of steel and cost £25 million.[48] Each harbour had three piers, a barge pier and an LST pier, each with one roadway, and a stores pier with two floating roadways.[49] When the Overlord plan was expanded in 1944, it was too late to enlarge the Mulberry harbours, so additional small craft shelters known as Gooseberries were provided, one for each invasion beach. The British Gooseberries were No. 3 at Arromanches on Gold Beach, No. 4 at Courseulles on Juno Beach and No. 5 at Ouistreham on Sword Beach.[48]

Construction of Mulberry B commenced near Arromanches on Gold Beach on 9 June and coasters began discharging inside the breakwaters on 11 June. The first coaster discharged over the store pier roadway on 18 June.[36] A severe storm—the worst recorded in June in forty years—swept over the channel between 19 and 22 June.[50] The storm halted discharge of personnel and supplies for 24 hours, destroyed Mulberry A and severely damaged Mulberry B. Components of Mulberry A were salvaged and used to repair and complete Mulberry B.[51] Phoenix caissons were filled with sand to give them greater stability.[52] The second roadway to the stores pier was opened on 6 July. By this time the sheltered area designed for 16 coasters was in use by seven Liberty ships and 23 coasters.[36] It exceeded its designed daily capacity of 6,100 tonnes (6,000 long tons), averaging 6,874 tonnes (6,765 long tons).[52] The ships discharged over their sides into DUKWs and Rhino ferries.[36] Ten of the eleven DUKW companies worked Mulberry B. Some 36 DUKWs were lost in the first five days.[53]

DUKWs were able to operate safely inside the harbour every day except during the storm. Due to it, the LST pier planned to service twenty LSTs per day from 18 June was not opened until 20 July and LSTs had to be dried out—beached and left stranded at low tide while unloading continued. Royal Navy misgivings about drying out store carrying LCTs had been overcome during the planning stages, but it now became necessary to dry out LSTs as well, with considerable consequent damage that was beyond the capacity of the naval repair teams, which slowed LST turnaround.[36][54] Because of the storm, only 19,446 tonnes (19,139 long tons) of stores were landed by 29 June instead of the planned 39,870 tonnes (39,240 long tons).[55] The main effect was a shortage of ammunition, particularly for the 25-pounders and 5.5-inch guns, for which demand had been unexpectedly heavy. A high priority was given to additional shipments, with petrol, oil and lubricant (POL) shipments cut to compensate.[54] On 20 June, the Navy agreed to allow ammunition ships to enter Mulberry B, even though this was acknowledged to be very dangerous. An additional 10,000 tonnes (10,000 long tons) arrived by 27 July, averting a crisis.[56]

Minor ports

In addition to the Mulberry, small ports were used; Courseulles, which was mainly used by fishing boats, had a draught of 2.9 metres (9 ft 6 in), making it suitable only for shallow-draught vessels, such as barges. A daily average of 860 tonnes (850 long tons) was unloaded there in June, rising to 1,500 tonnes (1,500 long tons) in July and August. Operations ceased on 7 September.[36]

Port-en-Bessin was operated as a bulk petroleum terminal, servicing both the British and American forces. Shallow-draught oil tankers drawing up to 4.3 metres (14 ft) could enter the port and larger tankers up to 5,000 gross register tons (14,000 m3) could discharge using Tombolas, floating ship-to-shore lines.[36] Two ship-to-shore lines were in operation by 25 July, and six tanker berths were in operation, with pipelines connected to the bulk petroleum storage terminal, which had a capacity of 10,000 tonnes (9,800 long tons) of petrol and 2,000 tonnes (2,000 long tons) of aviation fuel.[57] The port was opened to store ships on 12 June, and to tankers on 24 June. Some 87,000 tonnes (86,000 long tons) of petrol was discharged by 31 July, and a daily average of 11,304 tonnes (11,125 long tons) of stores were discharged until the port was closed on 25 September.[36]

Cherbourg was captured by the Americans on 27 June but it was very badly damaged and was not opened to shipping until 16 July.[58] Some 510 tonnes (500 long tons) of its daily capacity was allocated to the British. It contained the only deep-water berths in Allied hands and was useful in reducing the load on Port-en-Bessin. The railway line from Cherbourg to Caen commenced operation on 26 July, using rolling stock captured near Bayeux.[36] The lack of deep water berths meant that a large proportion of the supplies shipped went in coasters that could discharge at the small ports rather than in large, ocean-going Liberty ships.[59]

It was hoped that Cherbourg could handle large and awkward loads, but it had been so badly damaged that it was not sufficiently rehabilitated to do so until late August. In the meantime, they were shipped already loaded on transporters, or unloaded from lighters by cranes at Courseulles or Port-en-Bessin. Although manifests were flown across each day, there was still trouble identifying cargo. A commendable but misplaced desire to use all available cargo space often led to one type of stores overlaying another. The result was mixed loads of stores being unloaded into the DUKWs, with a slowing of their turnaround time if they had to deliver to two different inland dumps.[59]

To reduce turnaround time and wear on the DUKW tyres, which were in short supply, transshipment areas were established where the DUKWs could transfer their loads to ordinary lorries. There were timber platforms with a mobile crane at one end. DUKWs were loaded by depositing supplies on them over the side of ships in a cargo net. Each DUKW had been equipped with two of these in the UK. A control tower overlooking the port area used a loud hailer to direct the DUKWs to numbered platforms where a crane would remove the load. The DUKW would be given a replacement cargo net and head back out to the ship. The platform was large enough to permit some sorting of the stores. They would be loaded onto lorries backed up to the other side of the platform, either by hand or using roller runways.[60]

Because the shipping plan was so detailed, with everything carefully planned and scheduled in advance, timely and frequent alterations could not be tolerated. To make up for this, a system of "express coasters" was provided, which could carry a known tonnage of whatever was required on a given day. These carried unexpected and unforeseen demands, such as baling wire to help French farmers with their harvests.[59]

The British beaches were closed on 3 September 1944. By this time 221,421 tonnes (217,924 long tons) had been discharged through small ports, 615,347 tonnes (605,629 long tons) over open beaches, and 458,578 tonnes (451,335 long tons) through Mulberry B.[48] This meant that 25 per cent of the total tonnage had been landed through Cherbourg and the small ports, 12.5 per cent through Mulberry B, and 62.5 per cent over the beaches. The tonnage handled over the beaches greatly exceeded the expectations of the planners; but it is unlikely that the invasion would have been launched in the first place without the reassurance provided by the Mulberry.[61]

Ordnance

In the first four weeks, stores were landed in Landing Reserve packs, each made up of about 8,000 cases containing a mix of stores intended to support a brigade group or the equivalent for thirty days. After that, Beach Maintenance Packs were used. These were similar, but contained a wider variety of stores to support a division for thirty days. Each contained about 12,000 cases, weighing about 510 tonnes (500 long tons). Six Ordnance Beach Detachments landed on D-Day, along with two ammunition companies, two port ammunition detachments and a port ordnance detachment.[55][62]

The vessel carrying the recce party of 17 Advanced Ordnance Depot was torpedoed and most of the party was lost. A new party was organised, which arrived with the advance party on 13 June. The planned site for the depot near Vaux was satisfactory but at first, the area was occupied by two infantry divisions and the depot opened on 2 July. A vehicle park was established in the vicinity by 17 Vehicle Company on 13 June, mobile baths and laundries landed on 18 June and an industrial gas unit on 24 June to produce oxygen and acetylene for the workshops.[55]

The recce party of 14 Advanced Ordnance Depot landed on 28 June, and established the main RMA at Audrieu. The area was drained and 200 steel framed huts were erected. On 11 June, 17 Base Ammunition Depot arrived and began co-ordinating the stores and ammunition depots. When 15 Base Ammunition Depot arrived on 18 June, it took over those in 104 Beach Sub Area, while 17 Base Ammunition Depot took over those in 101 and 102 Beach Sub Areas. The average daily tonnage handled by the two base ammunition depots in the first two months of the campaign was 8,360 tonnes (8,230 long tons).[55]

Special "drowned" vehicle parks were established on the beaches for vehicles affected by water. Most swampings were caused not by faulty waterproofing but by landing craft discharging vehicles into more than 1.2 metres (4 ft) of water. The recovery of vehicles on the beaches was a hazardous enterprise owing to shellfire, mines and aircraft. Some 669 vehicles were brought in for repair by XXX Corps workshops between 8 June and 19 June, of which 509 were repaired, the remainder being written off. I Corps workshops established a "help yourself" park of written off vehicles from which spare parts could be salvaged, the process being faster than obtaining them from the Beach Maintenance Packs, where correctly identifying parts was difficult. When the Americans developed the Rhino tank attachment, the REME were asked to produce two dozen for British units. These were made in three days from steel salvaged from German beach obstacles.[63]

Seven British field artillery regiments were equipped with M7 Priest self-propelled guns, which required scarce American 105 mm ammunition and replaced them with Sexton 25-pounder self-propelled guns, delivered from Britain by 15 Advanced Ordnance Depot.[64] For Operation Totalize, the Canadians converted the surplus Priests into armoured personnel carriers, known as Kangaroos, by removing the guns and welding over the front apertures. The conversion was carried out by Canadian and REME workshops.[65]

Subsistence

In the Overlord planning, the 14-man ration pack that had proved satisfactory in the North African Campaign was adopted for use after the initial assault until bulk rations could be issued. The problem was how to feed the troops in the first 48 hours, as the assault packs used in Madagascar and Operation Torch had been found to be too heavy and bulky proportional to their nutritional value. A new 24-hour ration pack was therefore devised for Overlord. Two proposed ration packs were tested under field conditions in June 1943 and a new 24-hour ration was produced that combined the merits of both. The resulting 24-hour ration pack was a 17-kilojoule (4,000 cal) ration that weighed 990 grams (35 oz) and at 1,500 cubic centimetres (90 cu in) could fit into the standard British Army mess tin. The War Office then ordered 7.5 million of them, with a delivery date of 31 March 1944. Only by strenuous efforts was this achieved.[66]

The field service (FS) bulk ration was in general use by 21 July, although combat units continued using the ration packs for certain operations. The FS ration was entirely composed of preserved components but it was supplemented by shipments of fresh meat, fruit and vegetables. Hospital patients began to receive fresh bread on 13 June, and it was in general issue by 5 August. The mixture of tea, sugar and powdered milk in the ration packs was widely disliked and advantage was taken of an order authorising the issue of tea, sugar and milk to troops engaged in "heavy and arduous" night work. As a result, a large proportion of the 21st Army Group became engaged in such activities, unbalancing the reserve ration stocks. There were also large unforeseen demands for tommy cookers, compact portable stoves fuelled by hexamine tablets that could provide men in a front line trench with a hot cup of tea.[67]

Construction

Engineering works were initially the responsibility of the Chief Engineer, Second Army. Engineer store dumps were established at Tailleville (No. 1 Roadhead), Bayeux (No. 2 Roadhead), Ver-sur-Mer and Luc-sur-Mer, with the engineer base workshop at Le Bergerie. Some 9,000 construction personnel and 43,000 tonnes (42,000 long tons) of engineer stores were earmarked for shipment to Normandy by 25 July, but owing to the Channel storm and lack of demand due to the restricted lodgement area, only 6,000 personnel and 22,000 tonnes (22,000 long tons) of engineer stores were landed.[68] The main engineering tasks were the rehabilitation of the road network, the construction of airfields, the building of bridges, and the development of the bulk POL installation.[69]

By 26 July, the 21st Army Group had 152,499 vehicles in a lodgement area just 20 miles (32 km) wide and 10 miles (16 km) deep.[69] Despite little or no maintenance during the war, the roads were found to be in better condition than expected but soon deteriorated under constant heavy military traffic. Potholes were filled in and bypasses constructed around villages with narrow streets that were suitable for one-way traffic only. Some additional bridges were erected to remove bottlenecks.[68]

A lack of timber was foreseen by the planners and 12,000 tonnes (12,000 long tons) was earmarked for shipment. This included 18,000 piles 18 to 37 metres (60 to 120 ft) long and 47,000 pieces of squared timber. Five Canadian and two British forestry companies were in Normandy by the end of July, but the only sizeable source of timber in the lodgement area was the Cerisy Forest, where there was about 2,000 hectares (5,000 acres) of beech and oak. As in the Great War, much trouble was experienced with trees that had been hit by shrapnel; mine detectors were used on them with mixed results. By 26 September, the forestry companies had produced 24,000 tonnes (24,000 long tons) of sawn timber and 15,000 tonnes (15,000 long tons) of firewood; five companies produced 5,400 cubic metres (7,000 cu yd) of gravel for construction purposes from ten quarries.[70]

Five Royal Engineers airfield construction groups and an RAF airfield construction wing were active by the end of June. By the end of July, they had established seventeen airfields in the lodgement area, of which eight were surfaced with square meshed steel and one with bitumised hessian runways. Thirteen of these airfields were in operation by the RAF on 26 July. Problems were encountered with dust, which caused aircraft not fitted with air intake filters to suffer from excessive engine wear. The problem was largely overcome by wet weather in July.[68]

Salvage

A field salvage unit and field collecting unit arrived on 14 June. Prior to that, small dumps of salvaged equipment were established by the beach groups under the direction of the Second Army salvage officer. By 29 June, six salvage dumps were operational and those at No. 2 Roadhead had handled over 1,000 tonnes (1,000 long tons) of materiel. The base salvage dump was opened in the RMA on 24 July. A major task was retrieving airborne equipment that lay strewn about the landing and drop zones, including gliders. Souvenir hunters were responsible for the loss of instruments and fittings from many gliders. Large numbers of parachutes were not recovered, owing to their being prized by soldiers and civilians alike for their silk. By 25 July, 7,446 tonnes (7,328 long tons) of stores had been returned to ordnance.[71][72]

Casualties

Field ambulances landed with the assault brigades and each beach group had a self-contained medical organisation with two field dressing stations, two field surgical units and a field transfusion unit; most were operational within 90 minutes of H-Hour. Casualty clearing stations and hospitals began arriving on 8 June, and these were concentrated in three medical areas, around Hermanville-sur-Mer, Reviers and Ryes. On 12 June the installations in the Hermanville area moved to Douvres-la-Délivrande to make way for an expansion of the nearby ammunition depot. In late June the area around Bayeux was developed as the main Line of Communications hospital area. When HQ Line of Communications assumed administrative command on 13 July, it took over the Bayeux and Reviers groups, while responsibility for the Délivrande group passed to the First Canadian Army.[26]

The fighting was less severe than anticipated and casualties were lower. By 26 July, 44,503 British and 13,323 Canadian reinforcements had been dispatched to the 21st Army Group. By the same date, 38,581 casualties had been evacuated by sea. Air evacuation began on 13 June and by 26 July 7,719 casualties were evacuated to the UK.[26] Because of doubts about the availability of water in the lodgement area, large quantities of packaged potable water was shipped, particularly for the wounded on the beaches. The lower than expected casualties resulted in an accumulation of filled water containers which were not required.[54]

Casualties among the infantry were particularly severe; although infantrymen made only 20 per cent of the 21st Army Group, the infantry suffered 70 per cent of its casualties.[73] On 16 August it was decided to disband the 59th (Staffordshire) Infantry Division and the 70th Infantry Brigade of the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division to provide infantry reinforcements for other units. The reinforcement section of the Rear HQ of 21st Army Group became overwhelmed by personnel matters unrelated to reinforcements, like transfers and psychiatric cases and the Organisation and Selection of Personnel Branches of GHQ Second Echelon were sent out, arriving on 16 September. [74]

Provost

Six POW camps were placed at the disposal of 21st Army Group. Each was staffed to cater for 200 officers and 2,000 other ranks. The first of these arrived on 7 June, and was employed as a collection and transit centre. The next arrived on 11 June, and established a POW camp near Arromanches. Camps had been established in the UK for up to 25,000 prisoners but only 12,153 were captured by 26 July. Most were German but there were also Russians, Poles and other nationalities. Most were taken to the UK, but some were retained for labour duties. POW escorts were provided by the War Office and were based at Southampton. They crossed to Normandy on LSTs, collected the prisoners and took them back to the UK. This procedure did not work as well as planned, because the prisoners were not always ready to move when required, and the LSTs were unable to wait for them.[26]

The first CMP units to arrive landed on D-Day. These were three divisional provost companies, six beach provost companies, and two corps provost companies, which were used for traffic control. During the build-up phase, an additional company arrived with each division; four provost companies, four traffic control (TC) companies, and a vulnerable points (VP) company for each army and seven provost, seven TC and three VP companies for the Line of Communications Area. The VP companies were used to guard POWs. Delays in getting provost units ashore allowed traffic congestion to occur on the first two days, but the Line of Communications Area was established faster than planned when traffic congestion became a problem. One check point saw 18,836 vehicles pass it in a day, roughly one every four seconds. Despite all efforts, key towns like Courseulles and Bayeux soon became bottlenecks. Bypasses were built, and strict movement control was instituted. Under this regime, operational vehicles operated at night when the volume of administrative traffic was lighter.[71] Five movement control groups, Nos 6, 17, 18, 19 and 20, were assigned to 21st Army Group. They did not operate as units, but were dispersed among the different headquarters.[75]

Breakout and pursuit

On 25 July, the US First Army began Operation Cobra, the breakout from Normandy. The US 12th Army Group became active on 1 August with the US First and Third Armies under its command, all still commanded by the 21st Army Group HQ. This remained the case until General Dwight D. Eisenhower's Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) opened at Jullouville on 1 September. The rear headquarters of 21st Army Group joined the advanced headquarters at Vaucelles on 11 August. Falaise was captured on 16 August, and three days later the Canadians and Americans linked up, closing the Falaise Pocket. On 26 August, the 21st Army Group issued orders for an advance to the north to capture Antwerp. After a rapid advance (The Swan), the British Guards Armoured Division liberated Brussels on 3 September and the 11th Armoured Division captured Antwerp the following day.[76]

As the armies moved forward, No. 3 Army Roadhead was established for the First Canadian Army at Lisieux on 24 August and No. 4 Army Roadhead for the British Second Army near L'Aigle on 26 August. This was soon so far behind the advancing units that intermediate dumps known as "cushions" were established to which supplies required by the corps were sited forward of the roadhead in the direction in which the next roadhead would be established. The first of these, No. 1 Cushion, was established at Falaise on 21 August to support the First Canadian Army. No. 2 Cushion was established near Beauvais on 1 September and No. 3 near Doullens the next day. No. 5 Army Roadhead was sited on the road between Dieppe and Abbeville on 3 September, No. 6 Army Roadhead near Brussels on 6 September and No. 7 Army Roadhead near Béthune on 15 September. The 21st Army Group headquarters moved to Brussels on 23 September, and SHAEF moved to Versailles around the same time.[76]

Each army roadhead had a CRASC Supply Unit, who controlled two BSDs, four DIDs and four mobile field bakeries, and a CRASC Petrol Installation, who controlled five petrol depots. About 26,000 tonnes (26,000 long tons) of packaged fuel in jerry cans was held at a roadhead.[77] In mid-September, 12 Line of Communications Area became responsible for logistical activities south of the Seine, while 11 Line of Communications Area became responsible for those to the north.[78]

Transport

With the establishment of No. 6 Army Roadhead, the 21st Army Group line of communications was 400 miles (640 km) long, with the main depots still at the RMA and few stocks between them and the FMCs. A crucial decision was taken on 30 August to gamble on the early capture of Le Havre, Dieppe and Boulogne, and slash receipts from 16,300 to 7,100 tonnes (16,000 to 7,000 long tons) per day, to free transport, which would have been used to clear the beaches, for moving supplies forward of the RMA.[76] Vehicle maintenance was neglected but this presented few problems as most of the vehicles were new. An exception was 1,400 Austin K5 three-ton lorries, along with all their replacement engines, which were found to have faulty pistons and gave trouble.[79]

Additional general transport companies were shipped urgently from the UK and some new companies were formed in Normandy, increasing the number of companies for the British Second Army from six to thirty-nine.[80] The War Office agreed to loan another 12 general transport companies to the 21st Army Group but only five had arrived by 26 September.[81] These were formed from Anti-Aircraft Command and Mixed Transport Command.[82] A new headquarters called TRANCO was created on 10 September and all road and railway transport was withdrawn from the armies and assigned to it, with the mission of moving supplies from the RMA to the army roadheads.[76]

The First Canadian Army converted a tank transporter trailer into a load carrier by welding on steel plank normally used for airfield construction to form a base and sides. The experiment was successful and the modified tank transporters could carry 16.8 tonnes (16.5 long tons) of supplies, 37 tonnes (36 long tons) of ammunition, or 10 tonnes (10 long tons) of POL, except on narrow roads. The British Second Army converted a whole company in this manner.[83] The 21st Army Group initially had only two companies of tank transporters, and these were required in the UK until additional tank transporters arrived from the United States.[84]

Another expedient was to issue 30 additional lorries to four general transport companies that had enough relief drivers to man them. Two 10-ton companies were equipped with surplus 5-ton trailers. There were also eight DUKW companies, one of which was on loan to the US Army, and was involved in working Utah Beach. Two other companies were retained as DUKW companies and the remaining five were re-equipped with regular 3-ton lorries. In addition to the DUKW company, a 6-ton and a 3-ton general transport company were loaned to the US Army. These two companies were returned to the 21st Army Group on 4 September.[83][85] During the advance from the Seine, the Second Army employed only six of its eight infantry divisions, so the transport of two could be used to help maintain the other six.[86]

While the railway lines in northern France and Belgium had suffered damage, this was much less than of the lines south of the Seine. Commencing on 10 September, trains were loaded in the RMA and supplies shipped to a railhead near Beauvais, where they were loaded onto lorries that took them across the Seine. On the other side, they were loaded onto trains for the final journey to No. 6 Army Roadhead. Work began on a new 161-metre (529 ft) bridge over the Seine at Le Manoir on 8 September and it was opened a fortnight later. Some bridges over the Somme were also down but were bypassed by a diversion at Doullens. A bridge at Halle in Belgium was repaired by the Belgian authorities.[87]

Provision had been made in the Overlord plans for supply by air. Apart from supplying the Polish 1st Armoured Division for a short time, little use had been made of this, with the RAF freight service accounting for less than 200 tonnes (200 long tons) per week. In August, demand doubled from 12 to 25 long tons (12 to 25 t) per day. In the week ending 9 September 1,000 tonnes (1,000 long tons) of petrol and 300 tonnes (300 long tons) of supplies were delivered to airfields around Amiens, Vitry-en-Artois and Douai. The following week, 2,200 tonnes (2,200 long tons) of ammunition, 810 tonnes (800 long tons) of POL and 300 tonnes (300 long tons) of supplies were delivered. Evere Airport, the main airport at Brussels, was brought into use and 18,000 tonnes (18,000 long tons) was landed there over the next five weeks.[76][88]

After the liberation of Paris, it had become apparent that the Germans had stripped the capital of its food and other resources for themselves before their capitulation. Many Parisians were desperate and Allied soldiers even used their own meagre rations to help. The Civil Affairs of SHAEF therefore requested an urgent shipment of 3,000 tonnes (3,000 long tons) of food. A supply earmarked for just this purpose had been set aside at Bulford long before and on 27 August the first 510 tonnes (500 long tons) were delivered by RAF. This convoy labelled "Vivres Pour Paris" entered a day later, following which 450 tonnes (500 short tons) were delivered a day by the British. USAAF Dakotas were flown in which also delivered 500 tons a day. Along with French civilians outside Paris bringing in local resources, within ten days the food crisis in Paris was overcome.[89]

A minor crisis developed due to a shortage of jerry cans. Discipline regarding the return of containers was lax during the advance, resulting in the Second Army's path through France and Belgium becoming strewn with discarded cans, many of which were quickly appropriated by the civilian population. As the advance continued, the time taken for cans to be returned lengthened, and a severe shortage developed which took some time to overcome. The result was a depletion of stocks at the depots, and the imposition of petrol rationing.[90]

Ports

Antwerp was captured on 4 September but the port was unusable until 29 November because the Scheldt estuary remained in German hands until after the Battle of the Scheldt.[91] In the meantime, a port construction and repair company arrived on 12 September and began the rehabilitation of the port. The quays were cleared of obstructions and the Kruisschans Lock was repaired by December.[92] The port was opened to coasters on 26 November and deep draught shipping on 28 November when the Royal Navy completed minesweeping activity.[93]

After crossing the Seine, I Corps had swung left to take Le Havre. Although Saint-Valery-en-Caux was captured on 2 September, a full-scale assault was required to take Le Havre on 10 September, with support from the Royal Navy and RAF Bomber Command, which dropped almost 5,100 tonnes (5,000 long tons) of bombs. By the time the garrison surrendered on 12 September, the port was badly damaged. Unexpectedly, the port was allocated to the American forces.[91]

Le Tréport and Dieppe were captured by the Canadians on 1 September. Although the port facilities were almost intact, the approaches were extensively mined and several days of minesweeping were required; the first coaster docked there on 7 September.[91] The rail link from Dieppe to Amiens was ready to accept traffic the day before.[94] By the end of September, it had a capacity of 6,100 to 7,100 tonnes (6,000 to 7,000 long tons) per day.[78] Le Tréport became a satellite port of Dieppe.[95] Boulogne was captured on 22 September and Calais on 29 September.[96] Both were badly damaged and Boulogne was not opened until 12 October. Ostend was captured on 9 September and in spite of extensive demolitions it was opened on 28 September.[95]

Salvage

Enormous quantities of salvage were left at Falaise, and the HQ of the 197th Infantry Brigade was given responsibility for collecting it. Prisoners of war were used for labour. Depots for captured enemy stores were established at Cormelles-le-Royal for the area south of the Seine and at Amiens for north of the Seine. Top priority for collection was given to collecting jerry cans, which were in short supply. About 5,000 horses were captured, which were given to French farmers. By 26 September, 22,190 tonnes (21,840 long tons) of salvage had been collected and turned over to ordnance depots.[97]

Prisoners

Only small numbers of prisoners, mostly medical personnel who were used to care for wounded POWs, were retained for labour by 21st Army Group until August, when HQ Line of Communications was authorised to employ up to 40,000 of them. By 24 August, some 18,135 were being held and this climbed to 27,214 by 4 September. Thousands of prisoners were taken during the rapid pursuit phase and efforts were made to reduce prisoner numbers, shipping them to the UK via Arromanches, and later Dieppe. Numbers continued to increase, and exceeded 50,000 at the end of September, by which time over 90,000 prisoners had been shipped to the UK.[98]

Outcome

By mid-September, the Allies had liberated most of France and Belgium. During the first seven weeks the advance had been much slower than anticipated, and the short lines of communication had provided an opportunity to accumulate reserves of supplies. This had been followed by a breakout and pursuit in which the advance had been much faster than contemplated and the rapidity of the advance and the length of the line of communications had thrown up severe logistical problems that, together with increased German resistance, threatened to stall the Allied armies.[99]

The success of the 21st Army Group was in large part due to its logistics. The supply system developed by the British Army in the desert had become standard procedure, and the staffs and units serving the line of communications "reached a high degree of efficiency in their own particular task".[100] The support of the army group over the beaches and through the artificial Mulberry port constructed for the purpose was a logistical feat. So too was the rapid advance across France and Belgium, which exploited the success achieved in Normandy. This was made possible only by the enormous capacity and tremendous flexibility of the logistical system. "No Army or Navy", Eisenhower wrote, "was ever supported so generously or so well".[101]

The logistical performance of the 21st Army Group even outstripped that of the neighbouring US 12th Army Group, as the challenges facing the 21st Army Group were not as great; its lines of communications were shorter, fewer divisions were involved and some of the Channel ports had been captured, whereas the Breton ports intended to support the Americans, except for Saint-Malo, had not. Montgomery remained confident that it was still possible to end the war in 1944 but he was wrong as things were not carried out the way he wanted them.[99]

Notes

- ↑ French 2000, p. 106.

- ↑ French 2000, pp. 110–113.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 116.

- 1 2 French 2003, p. 273.

- 1 2 Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 239–241.

- ↑ French 2003, p. 275.

- ↑ French 2003, pp. 276–278.

- 1 2 Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 374–375.

- ↑ French 2000, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 278.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 248–249.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 276.

- ↑ Ellis 1962, pp. 31–32.

- 1 2 3 21st Army Group 1945, p. 2.

- ↑ Stacey 1960, p. 624.

- 1 2 Boileau 1954, pp. 301–303.

- ↑ Ellis 1962, p. 536.

- ↑ Mead 2015, pp. 126–129.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 247.

- ↑ Mead 2015, p. 137.

- 1 2 Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 274–275.

- ↑ Rogers & Rogers 2012, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 21st Army Group 1945, p. 7.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 273.

- 1 2 3 4 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 24–26.

- 1 2 Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 264–265.

- ↑ Ellis 1962, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Ellis 1962, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Ellis 1962, pp. 81, 87.

- ↑ Ellis 1962, p. 81.

- ↑ Roskill 1961, pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 21st Army Group 1945, p. 8.

- ↑ Higham & Knighton 1955, p. 372.

- 1 2 3 4 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Higham & Knighton 1955, pp. 373–374.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 277–278.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 283–286.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 297.

- ↑ Boileau 1954, p. 337.

- ↑ Boileau 1954, p. 340.

- ↑ Boileau 1954, pp. 340–342.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 283–285.

- ↑ French 2000, pp. 253–257.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 287–288, 396–397.

- ↑ French 2000, p. 118.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 254–256.

- 1 2 3 Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 256–259.

- ↑ Higham & Knighton 1955, p. 373.

- ↑ Ellis 1962, p. 272.

- ↑ Higham & Knighton 1955, pp. 369–370.

- 1 2 Ruppenthal 1953, p. 415.

- ↑ Boileau 1954, p. 330.

- 1 2 3 Carter & Kann 1961, p. 276.

- 1 2 3 4 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 18–20.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, p. 12.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, p. 14.

- ↑ Ruppenthal 1953, pp. 427, 464.

- 1 2 3 Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 281–282.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 286.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 280–281.

- ↑ "The Assault Landings in Normandy – Order of Battle, Second British Army". UK Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Fernyhough & Harris 1967, p. 290.

- ↑ Kennett & Tatman 1970, p. 233.

- ↑ Boileau 1954, p. 293.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 287.

- 1 2 3 21st Army Group 1945, p. 13.

- 1 2 Buchanan 1953, p. 179.

- ↑ Buchanan 1953, pp. 181–184.

- 1 2 21st Army Group 1945, p. 23.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 291–292.

- ↑ Carter, Ian. "Tactics and the Cost of Victory in Normandy". Imperial War Memorial. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Higham & Knighton 1955, p. 371.

- 1 2 3 4 5 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 31–36.

- ↑ Boileau 1954, pp. 341–342.

- 1 2 21st Army Group 1945, p. 40.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, p. 47.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 300.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 304.

- ↑ Boileau 1954, p. 350.

- 1 2 Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 303–304.

- ↑ Boileau 1954, pp. 325–326.

- ↑ Boileau 1954, pp. 349–350.

- ↑ Ellis 1968, p. 72.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 305.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 306.

- ↑ Coles & Weinberg 1964, pp. 744–745.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 308.

- 1 2 3 Carter & Kann 1961, pp. 312–313.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, p. 71.

- ↑ Higham & Knighton 1955, p. 380.

- 1 2 Carter & Kann 1961, p. 332.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, p. 35.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, p. 53.

- ↑ 21st Army Group 1945, p. 56.

- 1 2 Ellis 1968, pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 374.

- ↑ Carter & Kann 1961, p. 375.

References

- 21st Army Group (November 1945). The Administrative History of the Operations of 21 Army Group on the Continent of Europe 6 June 1944 – 8 May 1945. Germany: 21st Army Group. OCLC 911257199.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Boileau, D. W. (1954). Supplies and Transport, Volume I. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. London: The War Office. OCLC 16642033.

- Buchanan, A. G. B. (1953). Works Services and Engineer Stores. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. London: The War Office. OCLC 39083450.

- Carter, J. A. H.; Kann, D. N. (1961). Maintenance in the Field, Volume II: 1943–1945. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. London: The War Office.

- Coles, Harry Lewis; Weinberg, Albert Katz (1964). Civil Affairs: Soldiers Become Governors (PDF). United States Army in World War II: Special Studies. Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Ellis, L. F.; et al. (1962). Victory in the West – Volume I: The Battle of Normandy. History of the Second World War. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 456511724.

- Ellis, L. F.; et al. (1968). Victory in the West – Volume II: The Defeat of Germany. History of the Second World War. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 758329926.

- Fernyhough, Alan Henry; Harris, Henry Edward David (1967). History of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, 1920–1945. London: Royal Army Ordnance Corps. OCLC 493308862.

- French, David (2000). Raising Churchill's Army: The British Army and the War against Germany 1919–1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924630-0.

- French, David (2003). "Invading Europe: The British Army and Its Preparations for the Normandy Campaign, 1942–44". Diplomacy and Statecraft. 14 (2): 271–294. doi:10.1080/09592290412331308891. ISSN 0959-2296. S2CID 162384721.

- Higham, J. B.; Knighton, E. A. (1955). Movements. The Second World War 1939–1945 Army. London: The War Office. OCLC 16642055.

- Kennett, B. M.; Tatman, J. A. (1970). Craftsmen of the Army, Volume I, The Story of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-043-6. OCLC 792792582.

- Mead, Richard (2015). The Men Behind Monty. Barnsley, Yorkshire: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-47382-716-5. OCLC 922926980.

- Rogers, Joseph; Rogers, David (2012). D-Day Beach Force: The Men who Turned Chaos into Order. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6330-8. OCLC 939815028.

- Roskill, S. W. (1961). The War at Sea, Volume III: The Offensive, Part II: 1 June 1944 – 14 August 1945. London: HMSO. OCLC 916211988.

- Ruppenthal, Roland G (1953). Logistical Support of the Armies: May 1941 – September 1944 (PDF). Vol. I. Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 640653201. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Stacey, C. P. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Vol. III. Ottawa: The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 317352926. Retrieved 25 April 2021.