The Born–Haber cycle is an approach to analyze reaction energies. It was named after two German scientists, Max Born and Fritz Haber, who developed it in 1919.[1][2][3] It was also independently formulated by Kasimir Fajans[4] and published concurrently in the same journal.[1] The cycle is concerned with the formation of an ionic compound from the reaction of a metal (often a Group I or Group II element) with a halogen or other non-metallic element such as oxygen.

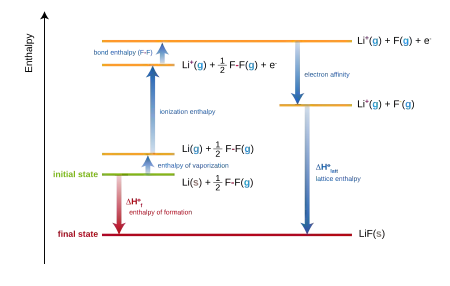

Born–Haber cycles are used primarily as a means of calculating lattice energy (or more precisely enthalpy[note 1]), which cannot otherwise be measured directly. The lattice enthalpy is the enthalpy change involved in the formation of an ionic compound from gaseous ions (an exothermic process), or sometimes defined as the energy to break the ionic compound into gaseous ions (an endothermic process). A Born–Haber cycle applies Hess's law to calculate the lattice enthalpy by comparing the standard enthalpy change of formation of the ionic compound (from the elements) to the enthalpy required to make gaseous ions from the elements.

This lattice calculation is complex. To make gaseous ions from elements it is necessary to atomise the elements (turn each into gaseous atoms) and then to ionise the atoms. If the element is normally a molecule then we first have to consider its bond dissociation enthalpy (see also bond energy). The energy required to remove one or more electrons to make a cation is a sum of successive ionization energies; for example, the energy needed to form Mg2+ is the ionization energy required to remove the first electron from Mg, plus the ionization energy required to remove the second electron from Mg+. Electron affinity is defined as the amount of energy released when an electron is added to a neutral atom or molecule in the gaseous state to form a negative ion.

The Born–Haber cycle applies only to fully ionic solids such as certain alkali halides. Most compounds include covalent and ionic contributions to chemical bonding and to the lattice energy, which is represented by an extended Born–Haber thermodynamic cycle.[5] The extended Born–Haber cycle can be used to estimate the polarity and the atomic charges of polar compounds.

Examples

Formation of LiF

The enthalpy of formation of lithium fluoride (LiF) from its elements in their standard states (Li(s) and F2(g)) is modeled in five steps in the diagram:

- Atomization enthalpy of lithium

- Ionization enthalpy of lithium

- Atomization enthalpy of fluorine

- Electron affinity of fluorine

- Lattice enthalpy

The sum of the energies for each step of the process must equal the enthalpy of formation of lithium fluoride, .

- V is the enthalpy of sublimation for metal atoms (lithium)

- B is the bond enthalpy (of F2). The coefficient 1/2 is used because the formation reaction is Li + 1/2 F2 → LiF.

- is the ionization energy of the metal atom:

- is the electron affinity of non-metal atom X (fluorine)

- is the lattice enthalpy (defined as exothermic here)

The net enthalpy of formation and the first four of the five energies can be determined experimentally, but the lattice enthalpy cannot be measured directly. Instead, the lattice enthalpy is calculated by subtracting the other four energies in the Born–Haber cycle from the net enthalpy of formation. A similar calculation applies for any metal other than lithium and/or any non-metal other than fluorine.[6]

The word cycle refers to the fact that one can also equate to zero the total enthalpy change for a cyclic process, starting and ending with LiF(s) in the example. This leads to

which is equivalent to the previous equation.

Formation of NaBr

At ordinary temperatures, Na is solid and Br2 is liquid, so the enthalpy of vaporization of liquid bromine is added to the equation:

In the above equation, is the enthalpy of vaporization of Br2 at the temperature of interest (usually in kJ/mol).

See also

Notes

- ↑ The difference between energy and enthalpy is very small and the two terms are often interchanged freely.

References

- 1 2 Morris, D.F.C.; Short, E.L. (6 December 1969). "The Born-Fajans-Haber Correlation". Nature. 224 (5223): 950–952. Bibcode:1969Natur.224..950M. doi:10.1038/224950a0. S2CID 4199898.

A more correct name would be the Born–Fajans–Haber thermochemical correlation.

- ↑ M. Born Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft 1919, 21, 679–685.

- ↑ F. Haber Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft 1919, 21, 750–768.

- ↑ K. Fajans Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft 1919, 21, 714–722.

- ↑ H. Heinz and U. W. Suter Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2004, 108, 18341–18352.

- ↑ Moore, Stanitski, and Jurs. Chemistry: The Molecular Science. 3rd ed. 2008. ISBN 0-495-10521-X. pp. 320–321.