| Bombing of Nijmegen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II Operation Argument (Big Week) | |||||||

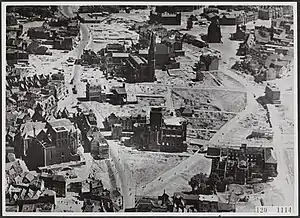

Police photo from 1945: in the foreground, parts of the centre mainly bombed in February '44; most buildings in the background were not destroyed until Operation Market Garden (September 1944).[1] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

(formation leader)[4][5] |

(commander Netherlands) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 14 B-24 Liberators[4] | Flaks | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | Railway station heavily damaged | ||||||

| c. 880 civilian deaths[6] | |||||||

The bombing of Nijmegen on 22 February 1944 was a target-of-opportunity aerial bombing raid by the United States Army Air Forces on the city of Nijmegen in the Netherlands, then occupied by Nazi Germany. In terms of the number of victims, it was one of the largest bombardments of a Dutch city during World War II. Officially, nearly 800 people (almost all civilians) were killed by accident due to inaccurate bombing but, because people in hiding were not counted, the actual death toll was likely higher. A large part of the historic city centre was destroyed, including Saint Steven's Church. Saint Augustine's Church and Nijmegen railway station (the intended target)[3] were heavily damaged as well.

The Dutch government-in-exile in London reestablished itself on the continent in early 1945 due to Canadian Army and other Allies' military efforts, and it avoided criticizing countries it relied upon for liberation and future security; thus national and local authorities largely remained silent on the bombing for decades, leaving survivors with unaddressed grief and questions, and allowing conspiracy theories to thrive. Although officials long maintained it had been an "erroneous bombardment", implying Nijmegen was the wrong target, historical research has shown that the attack was intentional, but executed poorly.

Background

A planned raid on the city of Gotha was part of the so-called 'Big Week' (official name: Operation Argument), a series of Allied bombardments on German aircraft factories to weaken the Luftwaffe in preparation for D-Day (June 1944). On 20 and 21 February, the first bombings had been carried out.[2][7]

At the time, it was common within the Allied air forces to attack secondary targets if the primary target could not be reached. These secondary targets were called targets of opportunity.[3][7] Because a bombing raid was risky and expensive (because of enemy fire and fuel), and the main target could often not be hit, an opportunistic bombing attack could still deal an important blow to the enemy, thus turning the operation into a partial success, and providing some return for the costs and risks.[3] The railway station area of Nijmegen was marked as such a target of opportunity, because the Allies knew that the Germans were using it for weapons transport.[3][7] There was pressure on the flyers to bomb anything if possible, because it was unsafe to land with unexpended bombs and, once the flyers had carried out 25 raids, they were given leave of absence.[2]

Course of events

Gotha mission cancelled

At 9:20[5] in the morning of 22 February, 177 American B-24 Liberator bombers, escorted by dozens of P-38 Lightning, P-47 Thunderbolt and P-51 Mustang fighters,[8] took off from RAF Bungay airbase near the Suffolk village of Flixton.[2] They flew in the direction of the German city of Gotha, where the Gothaer Waggonfabrik aircraft factory was producing Messerschmitt fighters and other Luftwaffe planes. This required a four-hour flight over German territory, making it a highly dangerous mission.[2] If Gotha could not be reached, Eschwege was the next target, and if even that failed, the pilots had to seek out a target of opportunity by themselves on the way back to their bases in Britain.[2]

Because the clouds were unusually high, the aircraft had trouble gathering into formation, and quickly lost sight of each other. In consequence, a considerable number of bombers broke off their mission 15 minutes after take-off and returned.[2] While still above the North Sea, the Americans were unexpectedly fired on by German fighters.[2] When the group passed over Nijmegen at 12:14 (CET), the air raid siren was activated by watchman Van Os, and residents ran for their shelters until it was safe.[9] Shortly after, around 13:00 when the bombers had reached about 10 miles into Germany, they received a message from command that the raid was cancelled due to too heavy cloud formations above Gotha for an effective bombardment; the units were recalled. Because Eschwege was still far out of reach, looking for targets of opportunity on the way back was now recommended.[2]

Airstrike

It was an extremely difficult task to turn around hundreds of planes and stay in formation, leading to a great deal of chaos and fragmenting the group into several squadrons who each sought their way back to Britain independently. Underway, they looked for targets of opportunity, and eventually the Dutch cities of Nijmegen, Arnhem, Deventer and Enschede were selected and attacked.[2] The squadron flying to Nijmegen consisted of twelve Liberators of the 446th Bombardment Group, which were joined by two detached Liberators of the 453rd Bombardment Group.[10] Beforehand, the flyers had been poorly informed about whether Nijmegen was a Dutch or a German city, whether German-occupied cities could or could not be bombed, and if so in what way, and they were negligent in finding out exactly which cities they were about to strike,[3] partly due to miscommunication that can be ascribed to technical problems such as a stuck radio operator's morse key.[2]

Watchman Van Os had given the clear sign at 13:16.[9] For reasons that are still unclear, he failed to activate the air raid siren a second time immediately 14 of the aircraft returned in Nijmegen's airspace, mere minutes after the clear sign had been given,[9] causing citizens not to run for cover as quickly as possible in time on this occasion.[2] Van Os stated afterwards that he did not ring the siren a second time until he heard explosions coming from the city centre.[9] At 13:28,[11] 144 brisant bombs (each weighing 500 pounds) and 426 shrapnel shells (20 pounds a piece) were dropped.[10] The actual target of opportunity, the train station area, was successfully hit. However, a considerable number of bombs fell on the city centre in residential areas, destroying homes, churches and other civil targets and killing hundreds of civilians.[3] After the fact, official Allied sources claimed that the pilots thought they were still flying above Germany, and had misidentified Nijmegen as the either the German city of Kleve (Cleves) or Goch. Yet some flyers themselves stated just an hour after landing in England that they had bombed Nijmegen, and a navigator even reported this in the air moments after the raid.[3]

Allied and German reactions

The Nazis reported that the Dutch government-in-exile in London had given permission for the airstrike on Nijmegen, and that it therefore was an intentional bombardment.[2] They made passionate attempts to exploit the bombing for propaganda: in public places, posters were hung with texts such as 'With friends like these, who needs enemies?' and 'Anglo-American Terror'. The German-controlled newspapers also furiously rebuked the Allies and the Dutch government-in-exile, one remarking "The Anglo-American pirates of the sky have once again executed the orders of their Jewish-Capitalist leaders with extraordinarily positive results". It appears that the propaganda was ineffective: seven months later, the American ground troops were welcomed as heroes by the inhabitants. Internal sources of the occupying government's Department for Popular Education and Arts even suggest the propaganda may have been counterproductive.[2]

On the day after the raid, the Allied air force launched an investigation: all air raids planned for that day were cancelled (also due to poor weather conditions), and all flyers and briefing officers involved were held on the base and questioned.[12] The full scale of the disaster was not yet clear on 23 February, but American aerial photographs taken during the attack that Dutch naval commander Cornelis Moolenburgh managed to obtain via the Royal Air Force left no doubt that Nijmegen (and especially civilian targets in its centre), Arnhem and Enschede had been hit. Moolenburgh informed Dutch ambassador Edgar Michiels van Verduynen, who confronted American ambassador Anthony Joseph Drexel Biddle, Jr. (until then ignorant of the events) on the matter in the presence of Dutch queen Wilhelmina. Biddle quickly informed U.S. President Roosevelt. American air force commander Henry H. Arnold was irritated when he discovered that the Dutch embassy had been informed earlier than he himself, and he henceforth denied Moolenburgh access to USAAF documents via the RAF (which Moolenburgh could however still obtain via secret service officer Kingman Douglass). The USAAF also refused to send out reconnaissance aircraft for taking photos assessing the exact damage in the three cities, whereupon the RAF offered and executed this task.[13] Wilhelmina demanded and received a written statement on what had happened, although it is unclear what it said.[12]

The American army command was relatively late in drawing lessons from the disorderly air raid, which had struck an ally's civilian population hard. Not until mid-May 1944, orders were given to seek out targets of opportunity at least 30 kilometres away from the Netherlands' border.[3]

Post-war investigation

Allied and Dutch governmental officials have maintained for decades that the bombing was a complete mistake, and the flyers supposedly did not know that they had bombed Nijmegen. This led to great frustration amongst Nijmegen's populace, which struggled with questions that were left unanswered. Concerning the real causes and motives of the attack, wild rumours and unlikely conspiracy theories sprang up and circulated widely. Although they were implausible, and contradicted each other, they satisfied a strong desire for an explanation, any explanation, for the tragic events.[14]

Brinkhuis (1984)

Amateur historian Alfons Brinkhuis, who as a 10-year-old boy had experienced the bombing of Enschede on the same day, became the first person to conduct an elaborate investigation into the archives, and interviewed dozens of eyewitnesses. In the summer of 1984, he published his conclusions in De Fatale Aanval 22 februari 1944. Opzet of vergissing? De waarheid over de mysterieuze Amerikaanse bombardementen op Nijmegen, Arnhem, Enschede en Deventer ("The Fatal Attack 22 February 1944. Intent or Error? The Truth About the Mysterious American Airstrikes on Nijmegen, Arnhem, Enschede and Deventer"). In doing so, he broke a taboo, and many facts were brought out in the open for the first time, although some of his research has been rendered obsolete by later findings. Brinkhuis' seven conclusions were:[15]

- Hundreds of bombers were unable to gather due to the high cloud formations, and had to cancel their mission prematurely.

- Formation of the attack group was not completed before German fighters carried out an unexpected counterstrike above the North Sea.

- Miscommunication occurred due to poor weather conditions, the American Mandrel radar jammer and especially the stuck morse key, preventing most aircraft from sending verifiable messages to the bases (vice versa was still possible, however).

- Because of this miscommunication, some units received the recall sooner than others, and therefore had to choose targets of opportunity far outside the normal routes.

- Because of the wind, planes were driven to the west without realising it (the clouds prevented them from seeing which country they were flying over).

- The Norden bombsights were set on Gotha as the target; there was no time to reprogram them, making precision bombing impossible.

- Navigators always flew based on schedules; they were not trained to orientate themselves based on the landscape. This enabled flyers to get lost when missions were not going according to plan.

Rosendaal (2006–09)

In 2006, history docent Joost Rosendaal of Radboud University Nijmegen started a new study into the bombardment,[16] which was eventually published in 2009 as Nijmegen '44. Verwoesting, verdriet en verwerking ("Nijmegen '44: Destruction, Grief, and Consolation"). In it, he classified the attack as an opportunistic bombing rather than an error. Rosendaal rejects the notion of an 'error', because the Americans were negligent in properly identifying which city to bomb. The Americans "intentionally bombed a target of opportunity, which, however, had not been unambiguously identified."[3]

Rosendaal added that the death toll was further increased by several disastrous circumstances. The switchboard operator, who normally directed emergency services, was killed during the raid, and without her communications were slower. Many water pipes had been destroyed, making firefighting efforts much harder and more time-consuming. Dozens of people were still alive, but stuck under the rubble; many burnt to death when flames reached them before they could be extinguished.[3]

Legacy

The Allied bombing of Nijmegen claimed almost as many civilian casualties as the German bombing of Rotterdam at the start of the war, but nationally it is not given nearly as much attention.[2] The population of Nijmegen was told not to express their emotions, because the bombardment had been carried out by an allied nation. Furthermore, it was officially maintained that it was an 'erroneous bombardment' (vergissingsbombardement), and the fact that the railway station area was the intended target of opportunity was covered up.[3] Roosendaal opined that the term 'error' does not do justice to what has happened.[3]

The memory of the February bombardment overshadows that of the city's destructive liberation during Operation Market Garden in September 1944 and the five months succeeding it, in which Nijmegen was an oft-shelled frontline city. This caused hundreds more casualties, which may have been prevented had the city been evacuated. The deaths in Nijmegen – over two thousand – make up 7% of all civilian war casualties in the Netherlands, well above the national average relative to its population size. Furthermore, it was long unclear how to commemorate these 'pointless' victims; there were enough monuments for soldiers and members of the resistance, but not of civilian deaths, and they were never part of any official memorial services.[4]

In 1984, a memorial service was held for the first time, and at the 1994 Nijmegen Storytelling Festival amidst great public interest, eyewitnesses and survivors were given the chance to speak after 50 years of silence.[2] Not until 2000, a monument was erected for the civilian casualties:[3] 'De Schommel' (The Swing) at the Raadhuishof. Annual memorial gatherings held on 22 February were attended by an increasing number of people in the 2010s.[17]

Daalseweg cemetery, victim monument 22-02-44.

Daalseweg cemetery, victim monument 22-02-44. Daalseweg cemetery, grave of Leo Jacobs, signaller of Saint Steven's Tower, 22-02-'44.[18]

Daalseweg cemetery, grave of Leo Jacobs, signaller of Saint Steven's Tower, 22-02-'44.[18] Daalseweg cemetery, chapel with a list of child victims 22-02-'44

Daalseweg cemetery, chapel with a list of child victims 22-02-'44 Daalseweg cemetery, chapel with a list of nurse victims JMJ_22-02-'44

Daalseweg cemetery, chapel with a list of nurse victims JMJ_22-02-'44 Daalseweg cemetery, two rows of war victim graves 22-02-'44

Daalseweg cemetery, two rows of war victim graves 22-02-'44 Saint Steven's Church bombing plaquette 22-02-'44

Saint Steven's Church bombing plaquette 22-02-'44 Graafseweg cemetery, monument 22-02-'44

Graafseweg cemetery, monument 22-02-'44 2017 metal plate marking the bombed area's edge

2017 metal plate marking the bombed area's edge

See also

References

- ↑ "Historische @tlas Nijmegen". Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "Bombardement van Nijmegen". Andere Tijden. NPO Geschiedenis. 20 January 2004. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Bombardement geen vergissing, wel een 'faux pas'". De Gelderlander. 21 February 2009. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Onno Havermans (28 March 2009). "Het bombardement was geen vergissing". Trouw. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- 1 2 Brinkhuis 1984, p. 29.

- ↑ Brinkhuis 1984, p. 100.

- 1 2 3 "Bombardement 22 februari 1944 Nijmegen". Oorlogsdoden Nijmegen. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ Jack McKillop. "Combat Chronology of the US Army Air Forces February 1944". USAAF Chronology. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Brinkhuis 1984, p. 86.

- 1 2 Brinkhuis 1984, p. 74.

- ↑ "Bombardement vaagde stadshart Nijmegen weg in 1 minuut". De Gelderlander. 15 February 2014. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- 1 2 Brinkhuis 1984, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Brinkhuis 1984, pp. 130–135.

- ↑ Brinkhuis 1984, pp. 7–10.

- ↑ Brinkhuis 1984, p. 138.

- ↑ "Onderzoek ook op internet". Algemeen Dagblad. 22 February 2007. Archived from the original on 19 September 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ "Steeds drukker bij herdenking bombardement Nijmegen". De Gelderlander. 22 February 2016. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ↑ "Site oorlogsdoden Nijmegen". Archived from the original on 19 September 2023. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

Literature

- Brinkhuis, Alfons (1984). De Fatale Aanval 22 februari 1944. Opzet of vergissing? De waarheid over de mysterieuze Amerikaanse bombardementen op Nijmegen, Arnhem, Enschede en Deventer (in Dutch). Weesp: Gooise Uitgeverij. p. 147. ISBN 9789073232013. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Joost Rosendaal Nijmegen '44. Verwoesting, verdriet en verwerking, uitg. Vantilt, Nijmegen (2009)

- Onno Havermans "Het bombardement was geen vergissing - Nijmegen leed zwaar onder de oorlog", Trouw, cahier Letter&Geest, 28 March 2009, p. 81.