| Blue petrel | |

|---|---|

| |

| In flight | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Procellariidae |

| Genus: | Halobaena Bonaparte, 1856 |

| Species: | H. caerulea |

| Binomial name | |

| Halobaena caerulea (Gmelin, 1789) | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

The blue petrel (Halobaena caerulea) is a small seabird in the shearwater and petrel family, Procellariidae. This small petrel is the only member of the genus Halobaena, but is closely allied to the prions. It is distributed across the Southern Ocean but breeds at a few island sites, all close to the Antarctic Convergence zone.

Taxonomy

The blue petrel was first described in 1777 by the German naturalist Georg Forster in his book A Voyage Round the World. He had accompanied James Cook on Cook's second voyage to the Pacific.[3] Forster did not give the blue petrel a binomial name, but when the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin updated Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae in 1789 he included a brief description of the bird, coined the binomial name Procellaria caerulea and cited Forster's book.[4] The blue petrel is now the only species placed in the genus Halobaena that was introduced for the blue petrel in 1856 by French naturalist Charles Lucien Bonaparte.[5][6] The name Halobaena combines the Ancient Greek hals, halos meaning "sea" with bainō meaning "to tread". The specific epithet caerulea is from Latin caeruleus meaning "blue".[7] The word "petrel" is derived from Saint Peter and the story of his walking on water. This is in reference to the petrel's habit of appearing to run on the water to take off.[8] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[6]

The blue petrel is a member of the order Procellariiformes. It shares certain identifying features with the rest of the order. First, it has nasal passages that attach to the upper bill called naricorns. The bills of Procellariiformes are unique in that they are split into between 7 and 9 horny plates. It also produces a stomach oil made up of wax esters and triglycerides that is stored in the proventriculus. This is used against predators as well as an energy rich food source for chicks and for the adults during their long flights.[9] Finally, it also has a salt gland that is situated above the nasal passage and helps desalinate its body, due to the high amount of ocean water it drinks. It excretes a high saline solution from their nose.[10]

Description

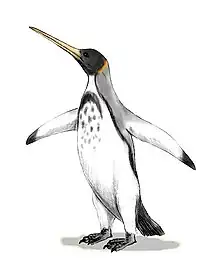

The blue petrel's plumage is predominantly blue-grey, with a dark "M" extending across the upperwing from wingtip to wingtip. It has a prominent black cap and white cheeks. It is white below apart from dark patches at the side of the neck. The square tail has a white tip. It has a slender black bill. It is 26–32 cm (10–13 in) in length, has a wing span of 62–71 cm (24–28 in) and weighs approximate 200 g (7.1 oz).[11]

Distribution and habitat

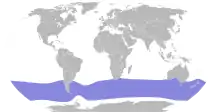

The blue petrel inhabits the southern oceans ranging as far north as South Africa, Australia and portions of South America. They mostly only breed in a narrow latitudinal band from 47° to 56° S on either side of the Antarctic Polar Front. Nesting on subantarctic islands, such as the Diego Ramírez Islands, the Crozet Islands, Kerguelen Islands, Macquarie Island, South Georgia, Prince Edward Island.[11]

In 2014 a breeding colony was discovered on Gough Island (40° S, 10° W), central South Atlantic Ocean, more than 700 km north of its known and usual breeding range. Breeding here appears to take place later than at colonies farther south, so although the discovery is recent it does not necessarily represent a recent range extension.[12]

Behaviour

Feeding

The blue petrel feeds predominantly on krill, as well as other crustaceans, small fish, squid and occasionally insects.[11] It can dive to a depth of up to 6.2 m (20 ft).[13]

Breeding

The blue petrel, like all members of the Procellariiformes, is colonial, and have large colonies. It nests in a burrow, and lays one egg per breeding attempt. Both parents incubate the egg for approximately 50 days and the chick fledges after 55 days. Skuas are the main danger for their eggs and chicks.

Conservation status

The blue petrel has a very large range and an estimate population of 3,000,000 adult birds and thus it is rated as Least Concern, by the IUCN.[1]

References

- 1 2 BirdLife International (2020). "Halobaena caerulea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22698102A181599271. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22698102A181599271.en. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- 1 2 3 Peters, James Lee, ed. (1931). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Forster, Georg (1777). A Voyage Round the World, in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, During the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5. Vol. 1. London: B. White, P. Elmsly, G. Robinson. p. 91.

- ↑ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 560.

- ↑ Bonaparte, Charles Lucien (1856). "Espèces nouvelles d'oiseaux d'Asie et d'Amérique, et tableaux paralléliques des Pélagiens ou Gaviae". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 42: 764–776 [768].

- 1 2 Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Petrels, albatrosses". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ↑ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 82, 185. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ↑ Gotch, A. T. (1995)

- ↑ Double, M. C. (2003)

- ↑ Ehrlich, Paul R. (1988)

- 1 2 3 Marchant, S.; Higgins, P.G., eds. (1990). "Halobaena caerulea Blue Petrel" (PDF). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1: Ratites to ducks; Part A, Ratites to petrels. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. pp. 508–515. ISBN 978-0-19-553068-1.

- ↑ Ryan, P.G.; Dilley, B.J.; Jones, C.; Bond, A.L. (2015). "Blue Petrels Halobaena caerulea discovered breeding on Gough Island". Ostrich. 86 (1–2): 193–194. doi:10.2989/00306525.2015.1005558. S2CID 86699478.

- ↑ Chastel, Olivier; Bried, Joel (1996). "Diving ability of blue petrels and thin-billed prions". The Condor. 98 (3): 627–629. doi:10.2307/1369575. JSTOR 1369575.

Sources

- Double, M. C. (2003). "Procellariiformes (Tubenosed Seabirds)". In Hutchins, Michael; Jackson, Jerome A.; Bock, Walter J.; Olendorf, Donna (eds.). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins. Joseph E. Trumpey, Chief Scientific Illustrator (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. pp. 107–111. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David, S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988). The Birders Handbook (First ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-671-65989-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gotch, A. F. (1995) [1979]. "Albatrosses, Fulmars, Shearwaters, and Petrels". Latin Names Explained A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File. pp. 191–192. ISBN 978-0-8160-3377-5.

External links

- Blue petrel on Birdlife International

- Blue petrel on ZipcodeZoo

- Blue petrel Photos

- Stamps (for French Southern and Antarctic Territory, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands)

- Blue petrel videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Blue petrel photo gallery VIREO