Bijelo Dugme | |

|---|---|

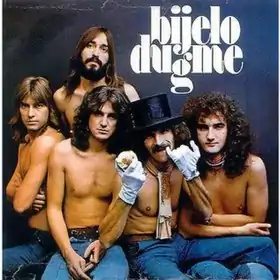

The default Bijelo Dugme lineup. Standing: Zoran Redžić; sitting, from left to right: Vlado Pravdić, Goran Bregović, Željko Bebek, Ipe Ivandić. | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Sarajevo, SR Bosnia and Herzegovina, SFR Yugoslavia |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1974–1989 (reunions: 2005) |

| Labels | Jugoton, Diskoton, Kamarad, Croatia Records |

| Past members | Goran Bregović Željko Bebek Jadranko Stanković Vlado Pravdić Ipe Ivandić Zoran Redžić Milić Vukašinović Laza Ristovski Điđi Jankelić Mladen Vojičić Tifa Alen Islamović |

Bijelo Dugme (trans. White Button) was a Yugoslav rock band, formed in Sarajevo, SR Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1974. Bijelo Dugme is widely considered to have been the most popular band ever to exist in the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and one of the most notable acts of the Yugoslav rock scene and Yugoslav popular music in general.

Bijelo Dugme was officially formed in 1974, although the members of its default lineup—guitarist Goran Bregović, vocalist Željko Bebek, drummer Ipe Ivandić, keyboardist Vlado Pravdić and bass guitarist Zoran Redžić—had previously played together under the name Jutro. The band's 1974 debut album Kad bi' bio bijelo dugme brought them nationwide popularity with its Balkan folk-influenced hard rock sound. The band's subsequent several studio releases, featuring similar sound, maintained their huge popularity, described by the Yugoslav press as "Dugmemania". Simultaneously, the band's material, especially their symphonic ballads with poetic lyrics—some written by poet and lyricist Duško Trifunović—was also widely praised by music critics. In the early 1980s, with the emergence of Yugoslav new wave scene, the band moved towards new wave, managing to remain one of the most popular bands in the country. After the departure of Bebek in 1983, the band was joined by new vocalist Mladen Vojičić Tifa, whom the band recorded only one self-titled album with. The band's next (and last) vocalist, Alen Islamović, joined the band in 1986, and with him Bijelo Dugme recorded two albums, disbanding in 1989. In 2005, the band reunited in the lineup that featured most of the musicians that passed through the band, including all three vocalists, for three concerts, in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, in Zagreb, Croatia and in Belgrade, Serbia, the concert in Belgrade being one of the highest-attended ticketed concerts of all time.

Bijelo Dugme is considered one of the most influential acts of the Yugoslav popular music, with a number of prominent figures of the Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav music scene citing them as an influence. Their works were critically acclaimed at the time of their release and in retrospect, with a number of their albums appearing on various lists of best Yugoslav rock albums, praised for the composition, musicianship, production and poetic quality of the lyrics. On the other hand, the band is often criticized by a part of musicians, music critics and audience who believe that the band's blend of rock music and Balkan folk paved the way for the appearance of turbo-folk music in the late 1980s and the 1990s. Bijelo Dugme's work remains popular in all former Yugoslav republics, the band often being considered one of the symbols of Yugoslav culture and their work being a frequent motif in various forms of yugo-nostalgia.

History

Background (1969–73)

Kodeksi (1969–71)

The band's history begins in 1969. At the time, the future leader of Bijelo Dugme, Goran Bregović, was the bass guitarist in the band Beštije (trans. The Beasts).[1] He was spotted by Kodeksi (The Codexes) vocalist Željko Bebek. As Kodeksi needed a bass guitarist, on Bebek's suggestion, Bregović became a member of the band.[1] The band's lineup consisted of Ismeta Dervoz (vocals), Edo Bogeljić (guitar), Željko Bebek (rhythm guitar and vocals), Goran Bregović (bass guitar), and Luciano Paganotto (drums).[1] At the time, the band Pro Arte was also interested in hiring Bregović, but he decided to stay with Kodeksi.[1] After performing in a night club in Dubrovnik, Kodeksi were hired to perform in a club in Naples, Italy.[1] However, the parents of the only female member, Ismeta Dervoz, did not allow her to go to Italy.[2] In Naples, the band initially performed covers of songs by Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience, but were soon asked by club owners to perform music more suitable for night clubs.[3] After two months, the band's guitarist Edo Bogeljić returned to Sarajevo to continue his studies, and Bregović switched to guitar.[3] Local Italian musician called Fernando Savino was brought in to play the bass,[3] but after he quit too, Bebek called up old friend Zoran Redžić, formerly of the band Čičak (Burdock).[1] Redžić in turn brought along his bandmate from Čičak Milić Vukašinović as replacement on drums for Paganotto, who also quit in the meantime.[1] Vukašinović brought new musical influences along the lines of what Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath were doing at the time. Additionally, he convinced Bregović, Bebek and Redžić on incorporating the new sound into their set,[1] and within two weeks of his arrival, Kodeksi were fired from all the clubs they were playing.[1]

The foursome of Bebek, Bregović, Redžić and Vukašinović stayed on the island of Capri and in 1970 relocated back to Naples.[1] At this time, the other three members persuaded Bebek to stop playing the rhythm guitar reasoning that it was not fashionable any more.[1] Bebek also had trouble adapting to the new material vocally. He would sing the intro on most songs and then step back as the other three members improvised for the remainder of songs, with Vukašinović taking the vocal duties more and more often.[1] After being a key band member only several months earlier, Bebek thought his role was gradually being reduced.[1] During the fall of 1970, he left Kodeksi to return to Sarajevo.[1]

Vukašinović, Bregović, and Redžić continued to perform, but decided to return to Sarajevo in the spring of 1971, when Bregović's mother and Redžić's brother came to Italy to persuade them to return home.[1] Upon returning, the trio had only one concert in Sarajevo, performing under the name Mića, Goran i Zoran (Mića, Goran and Zoran). At the concert, they performed covers of songs by Cream, Jimi Hendrix Experience, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, Ten Years After, Taste, Free, and managed to thrill the audience.[4] Soon after, the trio got the opportunity to appear in a Television Sarajevo show, but under the condition that they record a song of their own.[5] Hastily composed and recorded "Ja i zvijezda sjaj" ("Me and the Stars' Glow") was of poor quality and little artistic value,[5] which influenced Vukašinović's decision to move to London.[5] He left Sarajevo in late summer of 1971, and the trio ended their activity.[1]

Jutro (1971–73)

At the autumn of 1971, guitarist Ismet Arnautalić invited Bregović to form Jutro (Morning).[1] The band's lineup featured, alongside Arnautalić and Bregović, Redžić on bass, Gordan Matrak on drums and vocalist Zlatko Hodnik.[1] Bregović wrote his first songs as a member of Jutro.[1] The band had made some recordings with Hodnik when Bregović decided they needed a vocalist with "more aggressive" vocal style, so he invited Bebek to become the band's new singer.[6] With Bebek, the band recorded the song "Patim, evo, deset dana" ("I've Been Suffering for Ten Days Now"), which was, in 1972, released as the B-side of the single "Ostajem tebi" ("I Remain Yours"), which was recorded with Hodnik.[1] After the song recording, Bebek left the band to serve his mandatory stint in the Yugoslav People's Army, but the rest of the band decided to wait for his return to continue their activity.[1]

During Bebek's short leave from the army, the band recorded four more songs: "Kad bi' bio bijelo dugme" ("If I Were a White Button"), "U subotu, mala" ("On Saturday, Baby"), "Na vrh brda vrba mrda" (the title being a traditional tongue-twister which translates to "Willow Tree Is Moving on the Top of the Hill") and "Hop-cup" ("Whoopsie Daisy"), the first two appearing on a 7-inch single.[1] Dissatisfied with the music direction the band was moving towards, Arnautalić left the band at the end of 1972, convinced that the right to the name Jutro should belong to him.[1] For some time, guitarist Miodrag "Bata" Kostić, a former member of YU Grupa, rehearsed with the band, but this cooperation was soon ended.[6] YU Grupa were one of the pioneers in combining elements of the traditional music of the Balkans with rock, and Bregović would later state on number of occasions that this cooperation influenced Bijelo Dugme's folk rock sound.[1] After Matrak left the band, he was replaced by Perica Stojanović, who was shortly after replaced by former Pro Arte member Vladimir Borovčanin "Šento".[7] Borovčanin tried to secure a record contract with Jugoton, but failed, soon losing faith in his new band.[7] He and Redžić neglected rehearsals, and both left the band after an argument with Bregović.[7]

Redžić was replaced by Ivica Vinković, who was at the time a regular member of Ambasadori, but was not able to travel with the band on their Soviet Union tour.[8] Borovčanin was replaced by former Mobi Dik (Moby Dick) and Rok (Rock) member Goran "Ipe" Ivandić.[8] Instead of second guitar, Bregović decided to include keyboards in the band's new lineup. Experienced Vlado Pravdić, a former member of Ambasadori and Indexi, became Jutro's keyboardist.[9] The band prepared several songs for the recording in Radio Sarajevo's studio, but Arnautalić, still holding a grudge on his former bandmates, used his connections in Radio Sarajevo to get Jutro's recording sessions cancelled.[8] However, the band managed to make an agreement with producer Nikola Borota Radovan, who allowed them to secretly record the songs "Top" ("Cannon") and "Ove ću noći naći blues" ("This Night I'll Find the Blues") in the studio.[8] The intro to "Top" was inspired by traditional ganga music.[10] Soon after, Vinković rejoined Ambasadori, and was replaced by Jadranko Stanković, a former member of Sekcija (Section) and Rok.[11]

At this time, the band decied to adopt the name Bijelo Dugme. They decided to change the name because of the conflict with Arnautalić,[11] but also because of the existence of another, Ljubljana-based band called Jutro, which had already gained prominence on the Yugoslav scene.[1] As the band was already known for the song "Kad bi' bio bijelo dugme", they choose the name Bijelo Dugme.[1] The band officially started working under this name from January 1974.[1]

Željko Bebek years (1974–84)

"Shepherd rock" years: rise to fame and "Dugmemania" (1974–79)

In January 1974, with Borota, the band completed the "Top" and "Ove ću noći naći blues" recordings.[12] The band and Borota offered these recordings to the recently-established Sarajevo-based record label Diskoton, however, the label's top executive Slobodan Vujović rejected them, stating that the label already has a great number of signed acts and that Bijelo Dugme would have to wait for at least six months for the single to be released.[1][12] The decision would soon come to be considered the biggest business blunder in the history of Yugoslav record publishing.[1][12] On the same day the band were refused by Diskoton, they obtained a five-year contract with the Zagreb-based Jugoton label.[12] On 29 March 1974 "Top" and "Ove ću noći naći blues" were released on a 7-inch single that would eventually sell 30,000 copies.[10][13]

The band started promoting the single, performing mostly in smaller towns.[1] Stanković, unsatisfied with the agreement that only Bregović would compose the band's songs and feeling he did not fit in with the rest of the members, continued to perform with Bijelo Dugme, but avoided any deeper relations with other members.[14] Soon after, Bregović, Bebek, Ivandić and Pravdić decided to exclude him from the band.[15] Redžić was invited to join the band, which he accepted, despite his previous conflict with Bregović.[15] The following 7-inch single, featuring the songs "Glavni junak jedne knjige" ("The Main Character of a Book"), with lyrics written by poet Duško Trifunović, and "Bila mama Kukunka, bio tata Taranta" ("There Was Mommy Kukunka, There Was Daddy Taranta"), was almost at the same time released by both Jugoton and Diskoton, as Bregović signed contracts with both of the labels.[1] This scandal brought huge press covering and increased the single sales.[1]

The band had their first bigger performance at the 1974 BOOM Festival in Ljubljana, where they performed alongside Bumerang, Cvrčak i Mravi, Tomaž Domicelj, Hobo, Grupa 220, Jutro, Ivica Percl, S Vremena Na Vreme, YU Grupa, Drago Mlinarec, Nirvana, Grupa Marina Škrgatića and other acts[16] and were announced as "the new hopes".[1] The live version of "Ove ću noći naći blues" appeared on the double live album Pop Festival Ljubljana '74 – BOOM.[15] This was also Bijelo Dugme's first performance on which the members of the group appeared in their glam rock outfits, which brought them new attention of the media.[15] The band spent the summer performing in Cavtat and preparing songs for their first album.[1] They soon released their third single, with the songs "Da sam pekar" ("If I Was a Baker") and "Selma".[1] "Da sam pekar" was musically inspired by the traditional "deaf kolo", while "Selma", with lyrics written by poet Vlado Dijak, was a hard rock ballad.[17] Over 100,000 copies of the single were sold, becoming Bijelo Dugme's first gold record.[18]

During September, the band performed as the opening band for Tihomir "Pop" Asanović's Jugoslovenska Pop Selekcija, and during October, in studio Akademik in Ljubljana, they recorded their debut album Kad bi' bio bijelo dugme.[1] Several days before the album release, wanting to appear in the media as much as possible, Bijelo Dugme performed at the Skopje Festival, playing the song "Edna nadež" ("One Hope") by composer Grigor Koprov.[19] Bregović later described this event as "the greatest disgrace in Bijelo Dugme's career".[1] Bebek sung in bad Macedonian, and the band did not fit in well in the ambient of a pop festival.[1] On the next evening, the band performed, alongside Pop Mašina, Smak and Crni Biseri, in Belgrade's Trade Union Hall, on the Radio Belgrade show Veče uz radio (Evening by the Radio) anniversary celebration, and managed to win the audience's attention.[20] At the time, Bijelo Dugme cooperated with manager Vladimir Mihaljek, who managed to arrange the band to perform as an opening band on Korni Grupa's farewell concert in Sarajevo's Skenderija, which won them new fans, as about 15,000 people in the audience were thrilled with Bijelo Dugme's performance.[20]

Kad bi' bio bijelo dugme, featuring a provocative cover designed by Dragan S. Stefanović (who would also design covers for the band's future releases), saw huge success.[20] It brought a number of commercial hard rock songs with folk music elements, which were described as "pastirski rok" (shepherd rock) by journalist Dražen Vrdoljak.[20] This term was (and still is) sometimes used by the Yugoslav critics to classify Bijelo Dugme's sound.[21][22] The album featured the new versions of "Kad bi' bio bijelo dugme" and "Patim, evo, deset dana", "Sve ću da ti dam samo da zaigram" ("I'll Give You Everything Only to Dance"), ballad "Selma", blues track "Blues za moju bivšu dragu" ("Blues For My Ex-Darling") and rock and roll-influenced hit "Ne spavaj, mala moja, muzika dok svira" ("Don't You Sleep, Baby, while the Music Is Playing").[20] Immediately after the release, the album broke the record for the best selling Yugoslav rock album, previously held by YU Grupa's debut album, which was sold in more than 30,000 copies.[20] In February 1975, Bijelo Dugme was awarded a gold record at the Opatija Festival, as they, up to that moment, sold their debut album in more than 40,000 copies. The final number of copies sold was about 141,000.[20]

In late February 1975, Mihaljek organized Kongres rock majstora (Congress of Rock Masters), an event conceptualized as a competition between the best Yugoslav guitarists at the time.[20] Although Smak guitarist Radomir Mihajlović Točak left the best impression on the gathered crowd, he was not officially recognized due to his band not being under contract with Jugoton, a record label that financially supported the competition.[20] Instead, Vedran Božić (of Time), Josip Boček (formerly of Korni Grupa), Bata Kostić (of YU Grupa), and Bregović were proclaimed the best.[20] Each of them got to record one side on the Kongres rock majstora double album. While the other three guitarists recorded their songs with members of YU Grupa, Bregović decided to work with his own band and Zagreb String Quartet.[20] After the album was released, the four guitarists went on a joint tour, on which they were supported by YU Grupa members.[20] At the time, Bijelo Dugme released the single "Da mi je znati koji joj je vrag" ("If I Could Just Know What the Hell Is Wrong with Her"),[20] after which they started their first big Yugoslav tour.[20] In the spring of 1975, they were already considered the most popular Yugoslav band.[20] Soon after, Bebek took part in an event similar to Kongres rock majstora – Rock Fest '75, the gathering of the most popular Yugoslav singers of the time; besides Bebek, the event featured Marin Škrgatić (of Grupa Marina Škrgatića), Mato Došen (of Hobo), Aki Rahimovski (of Parni Valjak), Seid Memić "Vajta" (of Teška Industrija), Boris Aranđelović (of Smak), Hrvoje Marjanović (of Grupa 220), Dado Topić (of Time) and Janez Bončina "Benč" (of September).[23]

Before the recording of their second album, Bijelo Dugme went to the village Borike in Eastern Bosnia to work on the songs and prepare for the recording sessions.[20] The album Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu (What Would You Give to Be in My Place) was recorded in London during November 1975.[20] It was produced by Neil Harrison[20] who previously worked with Cockney Rebel and Gonzalez.[24] The bass guitar on the album was played by Bebek, as Redžić injured his middle finger just before the recording sessions started.[20] Nevertheless, Redžić was credited on the album, as he worked on the bass lines, and directed Bebek during the recording.[25] The lyrics for the title track were written by Duško Trifunović, while the rest of the lyrics were written by Bregović.[20] The band used the time spent in studio to record an English language song "Playing the Part", with lyrics written by lyricist Dave Townsend,[26] released on a promo single which was distributed to journalists.[20] The album was a huge commercial success, bringing hits "Tako ti je, mala moja, kad ljubi Bosanac" ("That's How It Is, Baby, When You Kiss a Bosnian"), "Došao sam da ti kažem da odlazim" ("I've Come to Tell You that I'm Leaving"), "Ne gledaj me tako i ne ljubi me više" ("Don't Look at Me like That and Kiss Me No More") and "Požurite, konji moji" ("Hurry Up, My Horses")[20] and selling more than 200,000 copies.[20] After the first 50,000 records were sold, Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu became the first Yugoslav album to be credited as diamond record.[27] After it was sold in more than 100,000 copies, it became the first platinum record in the history of Yugoslav record publishing, and after it sold more than 200,000 copies it was branded simply as "2× platinum record".[27]

After Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu release, the band went on a warming-up tour across Kosovo and Metohija. During the tour, injured Redžić was replaced by former Kamen na Kamen member Mustafa "Mute" Kurtalić.[20] The album's initial promotion was scheduled to take place on the band's New Year's 1976 concert at Belgrade Sports Hall in Belgrade, with Pop Mašina, Buldožer and Cod as the opening bands.[28] However, five days before New Year's, the band canceled the concert due to getting invited to perform for Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito at the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb, as part of the New Year's celebration being organized for him.[28] Their performance was, however, stopped after only several minutes, reputedly because of the loudness.[20]

The oldest visitors of their concerts—which for two months ravened like an epidemics through all Yugoslav cities with more than 30,000 people—are not older than 15. If they are, they are mental coevals of ten-year-olds. Even for than unripe age of man's life, the lyrics: 'I will give my life, 'cause you're mine only, in our love, my only love' must seem moronic. 'The Buttons'—original also when it comes to their costumes, on their five-inch heels, with earrings and trinkets—colored their 'lyrics' with 'traditional ghenes'. [...]

On their latest LP record there is a posterior with fingers pressed into it. They sold more than 600,000 records, and held 200 concerts during the last 365 days.

Bijelo Dugme is a peak of a wave of youth subculture. In this country there are also the League of Socialist Youth, the Institute for Social Issues, musical experts, serious publicists and press, radio and television. But neither institutions neither individuals had the courage (although they have interest) to establish the counterpoint to roistering advertising through something every society must have – through critical conscience. Not in order to execute or to anathematize, but in order to knowingly cover social life. Faced with the masquerade, the electronic music, the vulgar lyrics, society's scientific minds pushed their heads deep into the sand.

Energy, as we know, can not be lost, although it often seemed to me that today's youth had lost it. More and more young chairwarmers appeared, ready to ape the older ones [...] In Dom Sportova, that pure energy of youth appeared in a fascinating form, equal to the concrete colossus in which it emerged, but collectively subjected to rock syntax.

That sort of joy and that sort of spontaneity, that sort of sensitivity and that sort of togetherness are possible only with creative spirits, which do not bargain for their position, but simply share it with the others, the same, the equal. With the sounds that tear to pieces everything that does not subject to them (I myself felt minced), with blinding games of light, in the whirlpool of young bodies uncaring for their small spot, an event which will be remembered was created, an event which, in my opinion, Bijelo Dugme only accidentally set in motion.

That event was in the air, as a need of one generation of teenagers pinched between existing tepid culture and imperatives of their young nature. The instruments of Bijelo Dugme were only the electric lighter for those explosive masses, which started the run for their mythology, their culture, their values...

The generation which found its Bijelo Dugme will more likely find its Bach than the generation for which Bach is a social norm, the generation which is dressed in its formal suit and locked in its concert chair.

As Redžić had to leave the band due to his army obligations, a bass guitarist for live performances had to be hired.[31] Kurtalić asked for higher fees, so the new temporary bassist became Formula 4 leader Ljubiša Racić.[31] This lineup of the band went on a large Yugoslav tour.[20] In Sarajevo the band performed in front of 15,000 people and in Belgrade they held three sold-out concerts in Pionir Hall, with approximately 6,000 people per concert.[32] On the concerts, the band for the first time introduced a set of several songs performed unplugged.[32] The press coined the term "Dugmemanija" (Buttonmania) and the socialist public went into an argument over the phenomena.[20]

At the beginning of 1976, the band planned to hold a United States tour, however they gave up the idea after the suspicion that the planned concerts were organized by pro-ustaše emigrants from Yugoslavia.[20] The band did go to the United States, but only to record the songs "Džambo" ("Jumbo") and "Vatra" ("Fire"), which were released as Ivandić's solo single,[20] and "Milovan" and "Goodbye, Amerika" ("Goodbye, America"), which were released as Bebek's solo single.[20] The records represented the introduction of funk elements in Bijelo Dugme sound.[33] During the band's staying in America, Bregović managed to persuade Bebek, Pravdić and Ivandić to sign a waiver, with which they relinquished the rights to the name Bijelo Dugme in favor of him.[34] In June, the band members went to the youth work action Kozara 76, which was Bregović's response to the claims that the band's members were "pro-Western oriented".[20] At the beginning of autumn, Ivandić and Pravdić left the band due to their stints in te Yugoslav army.[20] They were replaced by Vukašinović (who, after Kodeksi disbanded, played with Indexi) and Laza Ristovski respectively. Ristovski's moving from Smak, at the time Bijelo Dugme's main competitors on the Yugoslav rock scene, saw huge covering in the media.[20]

The band prepared for the recording of their third album in Borike.[20] The album's working title was Sve se dijeli na dvoje, na tvoje i moje (Everything Is Split in Two, Yours and Mine) after a poem by Duško Trifunović.[20] Bregović did not manage to write the music on the lyrics (they were later used for the song recorded by Jadranka Stojaković),[20] so he intended to name the album Hoću bar jednom da budem blesav (For Once I Want to Be Crazy), but Jugoton editors did not like this title.[20] The album was eventually titled Eto! Baš hoću! (There! I Will!).[20] The album was once again recorded in London with Harrison as the producer and Bebek playing the bass guitar. It was released on 20 December 1976.[20] The album hits included hard rock tunes "Izgledala je malo čudno u kaputu žutom krojenom bez veze" ("She Looked a Little Bit Weird in a Yellow Sillymade Coat") and "Dede bona, sjeti se, de tako ti svega" ("Come on, Remember, for God's Sake"), folk-oriented "Slatko li je ljubit' tajno" ("It's So Sweet to Kiss Secretly"), simple tune "Ništa mudro" ("Nothing Smart", featuring lyrics written by Duško Trifunović) and two ballads, symphonic-oriented "Sanjao sam noćas da te nemam" ("I Dreamed Last Night that I Didn't Have You") and less complex "Loše vino" ("Bad Wine", written by Bregović and singer-songwriter Arsen Dedić and originally recorded by singer Zdravko Čolić).[20] In the meantime, Racić asked for higher payment, so he got fired.[20] He was replaced by Sanin Karić, who was at the time a member of Teška Industrija.[20] This lineup of the band went on the tour across Poland, on which they were announced as "the leading band among young Yugoslav groups" and held nine successful concerts.[20] After the band's return from Poland, Redžić and Ivandić rejoined them.[35] After leaving Bijelo Dugme, Vukašinović would form the hard rock/heavy metal band Vatreni Poljubac.[36]

In 1977 the band went on a Yugoslav tour, but experienced problems during it. The clashes within the band were becoming more and more frequent,[35] the concerts were followed by technical difficulties and bad reviews in the press,[37] and the audience was not interested in the band's concerts as it was during previous tours.[35] Three concerts in Belgrade's Pionir Hall, on 3, 4 and 5 March, were not well attended, and the second one had to be cut short after the shock wave from the Vrancea earthquake was felt.[38] The Adriatic coast tour was canceled, as well as concerts in Zagreb and Ljubljana for which the recording of a live album was planned.[35] After four years, Bijelo Dugme saw a decline in popularity and rumors about the band's disbandment appeared in the media.[35]

The band wanted to organize some sort of spectacle to help their decreased popularity.[35] On the idea of journalist Petar "Peca" Popović, the band decided to hold a free open-air concert at Belgrade's Hajdučka česma on 28 August 1977.[35] Jutro had already performed on this location in 1973, on a concert organized by the band Pop Mašina.[35] The concert would also be Bijelo Dugme's last concert before the hiatus due to Bregović's army duty.[35] The whole event was organized in only five days.[39] Between 70,000 and 100,000 spectators attended the concert, which was the biggest number of spectators on a rock concert in Yugoslavia up to that point.[35] After the opening acts – Slađana Milošević, Tako, Zdravo, Džadžo, Suncokret, Ibn Tup and Leb i Sol[39] – Bijelo Dugme played a very successful concert.[35] Despite the fact that the concert was secured by only twelve police officers,[40] there were no larger incidents.[41] Video recordings from the concert appeared in Mića Milošević's film Tit for Tat.[35] Eventually, it was discovered that the audio recordings could not be used for the live album, as the sound was bad due to technical limitations and the wide open space, so the band, on 25 October of the same year, played a concert in Đuro Janković Hall in Sarajevo, the recording of which was used for the live album Koncert kod Hajdučke česme (The Concert at Hajdučka česma).[35] Eventually, the only part of the Hajdučka česma concert that ended up on the album were the recordings of the audience's reactions.[35]

After Koncert kod Hajdučke česme was mixed, Bregović went to serve the army in Niš and the band went on hiatus;[35] Melody Maker wrote about Bijelo Dugme's hiatus as about an event "on the verge of national tragedy".[27] Redžić continued to work on the Koncert kod hajdučke česme recordings, and a live version of "Dede, bona, sjeti se, de tako ti svega" was later used as a B-side for the single "Bitanga i princeza" ("The Brute and the Princess"), released in 1979.[35] In June 1978, Bebek released his first solo album, the symphonic rock-oriented Skoro da smo isti (We're almost the Same),[35] which saw mostly negative reactions by the critics.[42] During the same year, Ristovski and Ivandić recorded the album Stižemo (Here We Come). The album, featuring lyrics by Ranko Boban, was recorded in London with Leb i Sol leader Vlatko Stefanovski on guitar, Zlatko Hold on bass guitar, and Goran Kovačević and Ivandić's sister Gordana on vocals.[35] Ristovski and Ivandić met with Bregović during his leave and played him the recordings, believing they could persuade him to let them compose for Bijelo Dugme.[42] After he refused, the two, encouraged by the positive reactions of the music critics which had the opportunity to listen to the material before the release, decided to leave Bijelo Dugme.[35][42] However, on 10 September, the same day for which the beginning of the promotional tour was scheduled, Ivandić, alongside Goran Kovačević and Ranko Boban, was arrested for owning hashish.[43] Ivandić was sentenced to spend three years in jail (Kovačević was sentenced to year and a half, and Boban to a year).[43] Before he went to serve the sentence, Ivandić went to psychiatric sessions to prepare for the life in prison. The psychiatrist he went to see was Radovan Karadžić.[44]

In June 1978, Bregović went to Sarajevo to receive a plaque from the League of Communist Youth of Bosnia and Herzegovina on the behalf of the band.[35] In the autumn of 1978, Pravdić returned to the band and drummer Dragan "Điđi" Jankelić, who participated in the recording of Bebek's solo album, became Bijelo Dugme's new drummer.[35] Jankelić was previously a member of Formula 4 (the lineup in which he played included both Ljubiša Racić and Jadranko Stanković), Rok, Čisti Zrak and Rezonansa.[45] Bijelo Dugme started preparing their new album in Niška Banja‚ but, as Bregović was still serving the army, they definitely reunited in Sarajevo on 1 November.[35] The new lineup of the band had their first performance in Skenderija on 4 December 1978.[46]

The band's fourth studio album was recorded in Belgrade and produced by Neil Harrison.[46] Several songs featured a symphonic orchestra.[35] The making of the album was followed by censorship. The original cover, designed by Dragan S. Stefanović and featuring female leg kicking male's genital area, was refused by Jugoton as "vulgar"; instead, the album ended up featuring a cover designed by Jugoton's designer Ivan Ivezić.[35] The verse "Koji mi je moj" ("What the fuck is wrong with me") was excluded from the song "Ala je glupo zaboravit njen broj" ("It's so Stupid to Forget Her Number"), and the verse "A Hrist je bio kopile i jad" ("And Christ was bastard and misery") from the song "Sve će to, mila moja, prekriti ruzmarin, snjegovi i šaš" ("All of That, My Dear, Will Be Covered by Rosemary, Snow and Reed") was replaced with "A on je bio kopile i jad" ("And he was bastard and misery").[35] The album Bitanga i princeza (The Brute and the Princess) was released in March 1979 and praised by the critics as Bijelo Dugme's finest work until then.[35][47] The album did not feature folk music elements, and brought songs "Bitanga i princeza", "Ala je glupo zaboravit njen broj", "Na zadnjem sjedištu mog auta" ("On the Back Seat of My Car"), "A koliko si ih imala do sad" ("How Many Have There Been?"), and emotional ballads "Ipak poželim neko pismo" ("Still, I Wish for a Letter"), "Kad zaboraviš juli" ("Once You Forget July") and "Sve će to, mila moja, prekriti ruzmarin, snjegovi i šaš", all becoming hits.[35] The album broke all the records held by their previous releases.[35] Twelve days before the start of the promotional tour, Pravdić had a car accident in which he broke his clavicle, so he performed on the initial several concerts using only one hand.[48] The tour, however, was highly successful.[35] The band managed to sell out Pionir Hall five times, dedicating all the money earned from these concerts (about 100,000 American dollars) to the victims of the 1979 Montenegro earthquake.[49] On some of the concerts they were accompanied by Branko Krsmanović Choir and a symphonic orchestra.[35] On 22 September, the band organized a concert under the name Rock spektakl '79. (Rock Spectacle 79) on Bellgrade's JNA Stadium, with themselves as the headliners. The concert featured numerous opening acts: Crni Petak, Kilo i Po, Rok Apoteka, Galija, Kako, Mama Rock, Formula 4, Peta Rijeka, Čisti Zrak, Aerodrom, Opus, Senad od Bosne, Boomerang, Prva Ljubav, Revolver, Prljavo Kazalište, Tomaž Domicelj, Metak, Obećanje Proljeća, Suncokret, Parni Valjak, Generacija 5 and Siluete.[50] More than 70,000 people attended the concert.[35]

At the time, Bregović wrote film music for the first time, for Aleksandar Mandić's film Personal Affairs, and the songs "Pristao sam biću sve što hoće" ("I Accepted to Be Anything They Want", with lyrics written by Duško Trifunović) and "Šta je tu je" ("Is What It Is") were recorded by Bijelo Dugme and released on a single record.[35] During 1980, Bregović spent some time in Paris, and the band was on hiatus.[35]

Doživjeti stotu: Jumping on the new wave bandwagon (1980–82)

At the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, the Yugoslav rock scene saw the emergence of the great number of new wave bands, closely associated to the Yugoslav punk rock scene. Bregović was fascinated by the new scene, especially by the works of Azra and Prljavo Kazalište.[51] During 1980, Bijelo Dugme decided to move towards new sound.[52]

In December 1980, Bijelo Dugme released new wave-influenced album Doživjeti stotu (Live to Be 100).[35] This was the first Bijelo Dugme album produced by Bregović.[35] Unlike the songs from the band's previous albums, which were prepared much before the album recording, most of the songs from Doživjeti stotu were created during the recording sessions.[53] As the recordings had to be finished before the scheduled mastering in London, Bregović used cocaine to stay awake, writing the lyrics in the nick of time.[54] The saxophone on the recording was played by jazz musician Jovan Maljoković and avant-garde musician Paul Pignon.[55] From the songs on Doživjeti stotu, only the new version of "Pristao sam biću sve što hoće" and "Pjesma mom mlađem bratu" ("The Song for My Little Brother") resembled Bijelo Dugme's old sound.[35] The songs "Ha ha ha" and "Tramvaj kreće (ili kako biti heroj u ova šugava vremena)" ("Streetcar Is Leaving (or How to Be a Hero in These Lousy Times)") were the first Bijelo Dugme songs to feature political-related lyrics.[35] The provocative cover, depicting plastic surgery, was designed by Mirko Ilić, an artist closely associated with Yugoslav new wave scene and appeared in three different versions.[35] In accordance with their shift towards new wave, the band changed their hard rock style: the members cut their hair short, and the frontman Željko Bebek shaved his trademark mustache.[56] Due to the new sound, Doživjeti stotu was met with a lot of skepticism, but most of the critics ended up praising the album.[56] At the end of 1980, the readers of Džuboks magazine polled Bijelo Dugme the Band of the Year, Bebek the Singer of the Year, Pravdić the Keyboardist of the Year, Jankelić the Drummer of the Year, Redžić the Bass Guitarist of the Year, Bregović the Composer, the Lyricist, the Producer and the Arranger of the Year, Doživjeti stotu the Album of the Year, and Doživjeti stotu cover the Album Cover of the Year.[56]

The band started their Yugoslav tour on 24 February 1981, with a concert in Sarajevo, and ended it with a concert in the club Kulušić in Zagreb, on which they recorded their second live album, 5. april '81 (5 April 1981).[35] The album, featuring a cover of Indexi song "Sve ove godine" ("All These Years"), was released in a limited number of 20,000 copies.[35] Bijelo Dugme performed in Belgrade several times during the tour: after two concerts in Pionir Hall, they performed, alongside British band Iron Maiden and Yugoslav acts Atomsko Sklonište, Divlje Jagode, Film, Aerodrom, Slađana Milošević, Siluete, Haustor, Kontraritam and others, on the two-day festival Svi marš na ples! (Everybody Dance Now!) held at Belgrade Hippodrome,[35] and during the New Year holidays they held three concerts in Hala Pinki together with Indexi.[57]

In early 1982, Bijelo Dugme performed in Innsbruck, Austria, at a manifestation conceptualized as a symbolic passing of the torch whereby the Winter Olympic Games last host city (Innsbruck) made a handover to the next one (Sarajevo).[35] On their return to Yugoslavia, the band's equipment was seized by the customs, as it was discovered that they had put new equipment into old boxes.[35] The band's record label, Jugoton, decided to lend 150,000,000 Yugoslav dinars to Bijelo Dugme, to pay the fine.[35] To regain part of the money as soon as possible, Jugoton decided to release two compilation albums, Singl ploče (1974-1975) (7-Inch Singles (1974-1975)) and Singl ploče (1976-1980).[35] To recover financially, during July and August 1982, the band went on a tour across Bulgaria, during which they held 41 concerts, two of them at the crowded People's Army Stadium in the capital Sofia.[58] As Jankelić went to serve the army in April, on this tour the drums were played by former Leb i Sol drummer Garabet Tavitjan.[58] At the end of 1982, the media published that Bregović was excluded from the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, with the explanation that he did not attend the meetings of the League in his local community.[57] However, due to the growing liberalization of the Yugoslav society, this event did not affect Bregović's and the band's career.[58]

At the end of 1982, Ivandić was released from prison and was approached to rejoin the band. With his return to the band, Bijelo Dugme's default lineup reunited.[59]

After Doživjeti stotu, Bebek's departure (1983–84)

At the beginning of 1983, Bregović, Redžić, Pravdić and Ivandić recorded a children's music album ...a milicija trenira strogoću! (i druge pjesmice za djecu) (...and Police Trains Strictness! (and Other Songs for Children)). The songs were composed by Bregović and the lyrics were written by Duško Trifunović.[58] It was initially planned pop rock singer Seid Memić "Vajta" to record the vocals, but eventually the vocals were recorded by eleven-year-old Ratimir Boršić "Rača", and the album was released under Ratimir Boršić Rača & Bijelo Dugme moniker.[58]

In February 1983, the band released the album Uspavanka za Radmilu M. (Lullaby for Radmila M.).[58] Bregović intended to release Uspavanka za Radmilu M. as Bijelo Dugme's farewell album and to dismiss the band after the tour.[58] The album was recorded in Skopje and featured Vlatko Stefanovski (guitar), Blagoje Morotov (double bass) and Arsen Ereš (saxophone) as guest musicians.[58] The songs "Ako možeš zaboravi" ("Forget, if You Can"), "U vrijeme otkazanih letova" ("In the Time of Canceled Flights"), "Polubauk polukruži poluevropom" ("Half-Spectre is Half-Haunting Half-Europe", the title referring to the first sentence of The Communist Manifesto) and "Ovaj ples dame biraju" ("Ladies' Choice") featured diverse sound, illustrating various phases in the band's career.[58] The album's title track is the only instrumental track Bijelo Dugme ever recorded.[58] Unlike the band's previous album, Uspavanka za Radmilu M. was not followed by a large promotion in the media,[60] but it was followed by the release of the videotape cassette Uspavanka za Radmilu M., which featured videos for all the songs from the album, which was the first project of the kind in the history of Yugoslav rock music.[61] The videos were directed by Boris Miljković and Branimir Dimitrijević "Tucko"[62] The video for the song "Ovaj ples dame biraju" was the first gay-themed video in Yugoslavia.[62] The song "Kosovska" ("Kosovo Song") featured Albanian language lyrics.[58] Written during delicate political situation in Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, the song represented Bregović's effort to integrate the culture of Kosovo Albanians into Yugoslav rock music.[63] Although lyrics were simple, dealing with rock music, the song caused certain controversies.[58][63]

Uspavanka za Radmilu M. did not bring numerous hits as the band's previous releases, however, the tour was very successful, and the audience's response made Bregović change his mind about dismissing the band.[58] After the tour, Bijelo Dugme went on a hiatus and Bebek recorded his second solo album, Mene tjera neki vrag (Some Devil Is Making Me Do It).[58] His last concert with Bijelo Dugme was on 13 February 1984, in Sarajevo Olympic Village.[58] Unsatisfied with his share of the profits in Bijelo Dugme, he decided to leave the band and dedicate himself to his solo career.[64] He left Bijelo Dugme in April 1984, starting a semi-successful solo career.[58] For a certain period of time, Bebek's backing band would feature Jankelić on drums.[65]

Mladen Vojičić "Tifa" years (1984–86)

After Bebek's departure, Alen Islamović, vocalist for the heavy metal band Divlje Jagode, was approached to join the band, but he refused fearing that Bebek might decide to return.[58] Eventually, the new Bijelo Dugme singer became then relatively unknown Mladen Vojičić "Tifa", a former Top and Teška Industrija member.[58] The band spent summer in Rovinj, where they held small performances in Monvi tourist centre, preparing for the upcoming album recording.[66] At the time, Ivandić started working with the synth-pop band Amila, fronted by his girlfriend-at-the-time Amila Sulejmanović, who would soon start to perform with Bijelo Dugme as a backing vocalist.[58]

At the time, Bregović, with singer Zdravko Čolić, formed Slovenia-based record label Kamarad, which would co-release Bijelo Dugme's new album with Diskoton.[58] The album was released in December 1984, entitled simply Bijelo Dugme, but is, as the cover featured Uroš Predić's painting Kosovo Maiden, also unofficially known as Kosovka djevojka (Kosovo Maiden).[58] The album featured both Ristovski and Pravdić on keyboards, and, after the album recording, Ristovski became an official member of the band once again.[58] Bijelo Dugme featured folk-oriented pop rock sound which had, alongside a cover of Yugoslav anthem "Hej, Sloveni" featured on the album, influenced a great number of bands from Sarajevo, labeled by press as "New Partisans".[58][67] The album featured a new version of "Šta ću nano dragi mi je ljut" ("What Can I Do, Mom, My Darling Is Angry"), written by Bregović and originally recorded by Bisera Veletanlić, Bijelo Dugme version entitled "Lipe cvatu, sve je isto k'o i lani" ("Linden Trees Are in Bloom, Everything's just like It Used to Be"), which became the album's biggest hit.[58] Other hits included "Padaju zvijezde" ("The Stars Are Falling"), "Lažeš" ("You're Lying"), "Da te bogdo ne volim" ("If I Could Only Not Love You") and "Jer kad ostariš" ("Because, When You Grow Old").[58] The song "Pediculis pubis" (misspelling of "Pediculosis pubis") featured Bora Đorđević, the leader of Bijelo Dugme's main competitors at the time, Riblja Čorba, on vocals; he co-wrote the song with Bregović and sung it with Bregović and Vojičić.[58] The album also featured Radio Television of Skopje Folk Instruments Orchestra, folk group Ladarice on backing vocals, Pece Atanasovski on gaida and Sonja Beran-Leskovšek on harp.[68]

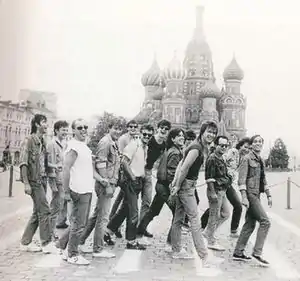

Bijelo Dugme was sold in more than 420,000 copies.[69] The tour was also very successful.[58] The band held a successful concert at Belgrade Fair in front of some 27,000 people (which was, up to that point, the biggest number of spectators on an indoor concert in Belgrade),[70] but also performed in clubs on several occasions.[58] The stylized army uniform in which the members of the band appeared on stage and the large red star from Kamarad logo were partially inspired by the works of Laibach.[71] In the summer of 1985, Bijelo Dugme, alongside Bajaga i Instruktori, represented Yugoslavia at the 12th World Festival of Youth and Students held in Moscow.[58] The two bands should have held their first concert on 28 July in Gorky Park.[72] The soundcheck, during which Yugoslav technicians played Bruce Springsteen and Pink Floyd songs, attracted some 100,000 people to the location.[73] Bajaga i Instruktori opened the concert, however, after some time, the police started to beat the ecstatic audience, and the concert was interrupted by the Soviet officials, so Bijelo Dugme did not have to opportunity to go out on the stage.[74] Fearing new riots, the Moscow authorities scheduled the second concert in Dinamo Hall, and the third one in the Moscow Green Theatre. The first one, held on 30 July, was attended by about 2,000 uninterested factory workers, and the second one, held on 2 August and also featuring British bands Misty in Roots and Everything but the Girl, by about 10,000 young activists with special passes.[74]

The concerts in Moscow were Vojičić's last performances with the band. Under the pressure of professional obligations, sudden fame and a media scandal caused by revelation of his LSD usage, he decided to leave the band.[58] After leaving Bijelo Dugme, Vojičić would first go on a tour with Željko Bebek and the band Armija B, then he would join Vukašinović's band Vatreni Poljubac, then heavy metal band Divlje Jagode (whose singer Alen Islamović replaced him in Bijelo Dugme), and eventually start a solo career.[58]

Alen Islamović years and disbandment (1986–89)

.jpg.webp)

After Vojičić's departure, Alen Islamović was once again approached to join the band. At the time, Islamović's band Divlje Jagode were based in London, working on their international career under the name Wild Strawberries. Doubting the success of their efforts, Islamović left them and joined Bijelo Dugme.[58]

The new album, Pljuni i zapjevaj moja Jugoslavijo (Spit and Sing, My Yugoslavia), was released in 1986. Inspired by Yugoslavism, with numerous references to Yugoslav unity and the lyrics on the inner sleeve printed in both Cyrillic and Latin alphabets, the album featured the already familiar pop rock sound with folk elements.[58] Bregović originally wanted the album to contain contributions from individuals known for holding political views outside of the official League of Communists ideology. To that end he and the band's manager Raka Marić approached three such individuals who were effectively proscribed from public discourse in Yugoslavia: pop singer Vice Vukov, who represented SFR Yugoslavia at the 1963 Eurovision Song Contest before seeing his career prospects marginalized after being branded a Croatian nationalist due to his association with the Croatian Spring political movement; painter and experimental filmmaker Mića Popović, associated with Yugoslav Black Wave film movement, who got a dissident reputation due to his paintings; politician and diplomat Koča Popović who, despite a prominent World War II engagement on the Partisan side as the First Proletarian Brigade commander that earned him the Order of the People's Hero medal, followed by high political and diplomatic appointments in the post-war period, nevertheless got silently removed from public life in 1972 after supporting a liberal faction within the Yugoslav Communist League's Serbian branch.[75] Bregović's idea was to have Vukov sing the ballad "Ružica si bila, sada više nisi" ("You Were Once a Little Rose"). However, despite Vukov accepting, the plan never got implemented after the band's manager Marić got arrested and interrogated by the police at the Sarajevo Airport upon returning from Zagreb where he met Vukov.[75] Mića Popović's contribution to the album was to be his Dve godine garancije (A Two-Year Warranty) painting featuring a pensioner sleeping on a park bench while using pages of Politika newspaper as blanket to warm himself, which Bregović wanted to use as the album cover. When approached, Mića Popović also accepted though warning Bregović of possible problems the musician would likely face.[75] Koča Popović was reportedly somewhat receptive to the idea of participating on the album, but still turned the offer down.[75] Eventually, under pressure from Diskoton, Bregović gave up on his original ideas.[76] A World War II holder of the Order of the People's Hero still appeared on the record, however, instead of Koča Popović, it was Svetozar Vukmanović Tempo. He, together with Bregović and children from the Ljubica Ivezić orphanage in Sarajevo, sang a cover of "Padaj silo i nepravdo" ("Fall, (Oh) Force and Injustice"), an old revolutionary song.[58] Instead of Popović's painting, the album cover featured a photograph of Chinese social realist ballet.[76] Vukmanović's appearance on the album was described by The Guardian as "some sort of Bregović's coup d'état".[58] The album's main hits were pop song "Hajdemo u planine" ("Let's Go to the Mountains"), "Noćas je k'o lubenica pun mjesec iznad Bosne" ("Tonight there's a Watermelon-like Full Moon over Bosnia"), and the ballads "Te noći kad umrem, kad odem, kad me ne bude" ("That Night, When I Die, When I Leave, When I'm Gone") and "Ružica si bila, sada više nisi".[58]

A number of critics, however, expressed their dislike for the album. One of them was Belgrade rock journalist Dragan Kremer. In 1987, Kremer appeared as guest on TV Sarajevo's show Mit mjeseca (Myth of the Month), a programme pitting Yugoslav rock critics against the country's rock stars, allowing critics to directly pose questions to musicians sitting across from them in the same studio. In the case of Kremer's appearance, however, Bregović wasn't in the studio due to being on tour—Kremer's taped questions were thus shown to Bregović while his reaction was filmed.[77] Expressing his opinion about the band's new direction, Kremer tore the album cover, which provoked Bregović to publicly insult Kremer, which became one of the larger media scandals of the time.[78][58] The incident however, did not affect the album sales. The tour was very successful, with the concert at Belgrade Fair featured opera singer Dubravka Zubović as guest.[58]

The double live album Mramor, kamen i željezo (Marble, Stone and Iron), recorded on the tour and produced by Redžić, was released in 1987.[58] The title song was a cover of a hit by the Yugoslav 1960s beat band Roboti.[58] The album offered a retrospective of the band's work, featuring songs from their first singles to their latest album.[58] The album featured similar Yugoslavist iconography as the bands' previous two releases: the track "A milicija trenira strogoću" begins with "The Internationale" melody, during the intro to "Svi marš na ples" Islamović shouts "Bratsvo! Jedinstvo!" ("Brotherhood! Unity!"),[58] and the album cover features a photograph from the 5th Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.[79] Mramor, kamen i željezo was the band's last album to feature Vlado Pravdić. He left the band after the album release, dedicating himself to business with computers.[80] However, he continued to occasionally perform with the band, on larger concerts,[80] and was, until the end of the band's activity, still considered an official member.[56][81]

At the end of 1988, the album Ćiribiribela was released.[80] Recorded during the political crisis in Yugoslavia, the album was marked by Bregović's pacifist efforts: the album featured Edward Hicks' painting Noah's Ark on the cover, the song "Lijepa naša" ("Our Beautiful") featured the national anthem of Croatia "Lijepa naša domovino" ("Our Beautiful Homeland") combined with the Serbian traditional World War I song "Tamo daleko" ("There, Far Away"),[80] and the title track featured lyrics about a love couple which decides to "stay at home and kiss" if the war starts.[82] The album's biggest hit was "Đurđevdan je, a ja nisam s onom koju volim" ("It's St. George's Day, and I'm Not with the One I Love'"), based on traditional Romani song "Ederlezi" and featuring Fejat Sejdić Trumpet Orchestra.[80] Other hits included "Evo zakleću se" ("Here, I'll Make A Vow"), "Ako ima Boga" ("If There Is God"), "Šta ima novo" ("What's New"), "Nakon svih ovih godina" ("After All These Years"), pop-influenced "Napile se ulice" ("The Streets Are Drunk") and Dalmatian folk music-inspired "Ćirbiribela".[80] After the album release, Radio-Television Belgrade wanted to make a video for the song "Đurđevdan je, a ja nisam s onom koju volim". The original idea was for the video to feature iconography inspired by the Serbian Army in World War I.[83] The video was recorded in the village Koraćica in Central Serbia.[83] The band came to the recording not knowing anything about the video concept.[84] They should have worn uniforms (without any insignia) and old weapons, but Islamović thought the idea was too "pro-war", so refused to wear a uniform.[84] Eventually, the band and the director reached an agreement: everyone, except Islamović, wore Serbian traditional costumes, with only several of the original props used.[85] However, after the video was recorded, the Radio-Television Belgrade editors themselves decided not to emit it, fearing it might remind of the Chetnik movement.[85]

At the beginning of 1989, the band went on a tour which should have lasted until 1 April.[80] The concert in Belgrade, held in Belgrade Fair on 4 February, was attended by about 13,000 people.[86] The concert featured Dubravka Zubović, the First Singing Society of Belgrade, the Fejat Sejdić Trumpet Orchestra and klapa Trogir.[86] The concert in Sarajevo's Zetra, held on 11 February, was also very successful; it was attended by more than 20,000 people.[86] However, on some concerts in Croatia, the audience booed and threw various objects on stage when the band performed their pro-Yugoslav songs.[86]

After the concert in Modriča, held on 15 March, with four concerts left until the end of the tour, Islamović checked into a hospital with kidney pains.[87] This event revealed the existing conflicts inside the band: Bregović claimed that Islamović had no problems during the tour,[87] while the band's manager, Raka Marić, stated that Bijelo Dugme would search for a new singer for the planned concerts in China and Soviet Union.[88] Bregović went to Paris, leaving Bijelo Dugme's status opened for speculations.[80] In 1990, the compilation album Nakon svih ovih godina was released, featuring recordings made between 1984 and 1989.[80] As Yugoslav Wars broke out in 1991, it became clear that Bijelo Dugme would not continue their activity.[80]

Post-breakup

Bregović continued his career as a film music composer, cooperating mostly with Emir Kusturica.[80] Redžić moved to Finland, where he worked as a producer, and after the Bosnian War ended, he returned to Sarajevo, where he opened a rock club.[80] Ristovski continued to record solo albums and worked as a studio musician. During the 1990s he worked with glam metal band Osvajači and his former band Smak.[80] Islamović, who recorded his first solo album Haj, nek se čuje, haj nek se zna (Hey, May All Hear, Hey, May All Know) in 1989, started a semi-successful solo career.[80]

On 12 January 1994, Ivandić died after falling from the sixth floor of the Hotel Metropol in Belgrade. After a police investigation, his death was officially declared a suicide. However, during the years, a number of his family members, friends and bandmates—including Bregović, Bebek, Ristovski, Vojičić, Vukašinović and Amila Sulejmanović—expressed doubts about the investigators' conclusions.[89][90][91][92][93] Bregović stated that in the years following his release from prison Ivandić used to sleepwalk, and that he might have fallen from the building's sixth floor while sleepwalking.[93] Vojičić, Vukašinović and several of Ivandić's friends expressed their belief that Ivandić was murdered by loan sharks.[92][93]

In 1994, the double compilation album Ima neka tajna veza (There's Some Secret Connection), featuring Dragan Malešević Tapi's painting Radost bankrota (The Joy of Bankruptcy) on the cover, was released.[80]

2005 reunion

Bregović, who during the 1990s became one of the most internationally known modern composers of the Balkans, on numerous occasions stated that he will not reunite Bijelo Dugme.[80] However, in 2005, Bijelo Dugme reunited, with Goran Bregović on guitar, Željko Bebek, Mladen Vojičić and Alen Islamović on vocals, Zoran Redžić on bass guitar, Milić Vukašinović and Điđi Jankelić on drums and Vlado Pravdić and Laza Ristovski on keyboards.[80] The reunion saw huge media attention in all former Yugoslav republics,[94] accompanied by various forms of yugonostalgia.[95]

The band held only three concerts: in Sarajevo, at Koševo City Stadium, Zagreb, at Maksimir Stadium, and Belgrade, at Belgrade Hippodrome.[80] The concerts featured a string orchestra, a brass band, klapa group Nostalgija and two female singers from Bregović's Weddings and Funerals Orchestra.[96] During the concerts, Bregović, Redžić, Pravdić and Ristovski performed during the whole set, while Vukašinović and Jankelić changed on drums.[97] Islamović opened the concerts in Sarajevo and Zagreb, and Vojičić opened the concert in Belgrade. Bebek sung third on all three concerts.[97] The concerts also featured an unplugged section, during which Bregović and Bebek played guitars and all three singers performed.[97] The concert in Sarajevo attracted about 60,000 people,[98] and the concert in Zagreb was attended by more than 70,000 people.[99] For the concert in Belgrade, more than 220,000 tickets were sold, but it was later estimated that it was attended by more than 250,000 people,[98] making it one of the highest-attended ticketed concerts of all time. However, the concert in Belgrade was much criticized due to inadequate sound system.[80][98] The live album Turneja 2005: Sarajevo, Zagreb, Beograd (2005 Tour – Sarajevo, Zagreb, Belgrade) recorded on the tour was released.[80]

Post-2005

Laza Ristovski died in Belgrade on 6 October 2007, following years of battle with multiple sclerosis.[100]

In 2014, Raka Marić made an attempt to reunite Bijelo Dugme once again to mark the band's 40th anniversary, but the agreement could not be reached, despite the members being interested in a new reunion.[101] Eventually, Goran Bregović marked 40 years since the formation of the band and the release of their debut album with a series of concerts with his Weddings and Funerals Orchestra, featuring Alen Islamović as vocalist.[101] To mark the anniversary, Croatia Records released a box set entitled Box Set Deluxe. The box set, released in a limited number of copies, features remastered vinyl editions of all studio albums, and the reissue of the band's first 7-inch single as bonus.[102]

Influence, legacy and criticism

Bijelo Dugme is the most important phenomenon in the last quarter of the 20th century in Yugoslav culture. In a socialist culture, which shyly searched for its path outside of determined framework of values, they were a phenomenon of overturning importance. They promoted the necessity of talent, the exigency of authenticity, the importance of attitude, the need for complete dedication, the high level of professionalism and the modern package. They were the biggest mass concept of Yugoslavia and the first mass concept not financed by the state. During their entire career, they had the endless love of the audience, the constant envy of their colleagues and divided sympathy of the establishment.

They defined rock culture and defined teenagers as an organised category. They fought for the freedom of taste, by then unimaginable in socialism, and won. They were one of the rare capitalist establishments in former Yugoslavia and the best advertisers of Yugoslavia's freedoms. They lived and worked in accordance to all the attributes of the Western rock culture. There was everything present in all big biographies of rock: big numbers, the euphoria of fans, all the vices (especially sex) except gambling, the inexplicable circumstances and tragic deaths. It is believed that they are the only ones in Yugoslavia who made big money from rock music. They set new standards in the entertainment industry and kept lifting them up. They fulfilled all the dreams of Yugoslav scene – except one: they did not step out on the world stage side by side with the biggest stars of the time, although they had the capacity to do that. Bijelo Dugme was maybe the biggest collateral damage of the Cold War when it comes to music: they couldn't go neither to the East, neither to the West. Then again, Bijelo Dugme is the only proof that the classic rock 'n' roll career is possible outside of English language.

-Dušan Vesić in 2014[103]

Bijelo Dugme is generally considered to have been the most popular act ever to appear in SFR Yugoslavia and its successor countries, inspiring many artists from different musical genres. The musicians that were, in their own words, influenced by Bijelo Dugme include guitarist and leader of Prljavo Kazalište Jasenko Houra,[104] singer and former Bulevar and Bajaga i Instruktori member Dejan Cukić,[105] guitarist and former leader of KUD Idijoti Aleksandar "Sale Veruda" Milovanović,[106] singer and former Merlin leader Dino Merlin,[107] and others. The acts that recorded covers of Bijelo Dugme songs include Aska,[108] Srđan Marjanović,[109] Regina,[110] Revolveri,[111] Prljavi Inspektor Blaža i Kljunovi,[112] Viktorija,[113] Sokoli,[80] Massimo Savić,[114] Vasko Serafimov,[115] Zoran Predin and Matija Dedić,[116] Branimir "Džoni" Štulić,[117] Teška Industrija,[118] Texas Flood[119] and others. The band's work has been parodied by Paraf,[120] Gustafi,[121] Rambo Amadeus,[122] S.A.R.S., and others. The song "Ima neka tajna veza" was performed by Joan Baez on her 2014 concerts in Belgrade and Zagreb.[123] In 1991, on Nirvana's concert in Muggia, Italy, Krist Novoselic jokingly introduced his band as Bijelo Dugme to the crowd consisting mostly of Slovenes.[124]

There were several books written about the band: Istina o Bijelom dugmetu (The Truth about Bijelo Dugme, 1977) by Danilo Štrbac, Bijelo Dugme (1980) by Duško Pavlović, Ništa mudro (1981) by Darko Glavan and Dražen Vrdoljak, Lopuže koje nisu uhvatili (Rascals That Weren't Caught, 1985) by Dušan Vesić, Bijelo Dugme (2005) by Asir Misirlić, Bijelo Dugme – Doživjeti stotu (2005) by Zvonimir Krstulović, Kad bi bio bijelo dugme (2005) by Nenad Stevović, Kad sam bio bijelo dugme (When I Was a White Button, 2005) by Ljubiša Stavrić and Vladimir Sudar[80] and Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu (2014) by Dušan Vesić.[125]

In 1994, Radio Television of Serbia aired a four-part documentary about the band entitled Nakon svih ovih godina.[80] In 2010, Igor Stoimenov directed a documentary about the band, entitled simply Bijelo Dugme.[126] In 2015, Robert Bubalo, Renato Tonković and Mario Vukadin directed a documentary film about Ivandić entitled Izgubljeno dugme (The Lost Button).[127]

The book YU 100: najbolji albumi jugoslovenske rok i pop muzike (YU 100: The Best albums of Yugoslav pop and rock music), published in 1998, features eight Bijelo Dugme albums: Bitanga i princeza (polled No. 10), Kad bi bio bijelo dugme (polled No. 14), Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu (polled No. 17), Bijelo Dugme (polled No. 28), Eto! Baš hoću! (polled No. 31), Doživjeti stotu (polled No. 35), Pljuni i zapjevaj moja Jugoslavijo (polled No. 53), and Koncert kod Hajdučke česme (polled No. 74).[128] The list of 100 greatest Yugoslav album, published by Croatian edition of Rolling Stone in 2015, features three Bijelo Dugme albums, Bitanga i princeza (ranked No. 15),[129] Eto! Baš hoću! (ranked No. 36)[130] and Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu (ranked No. 42).[131] In 1987, in YU legende uživo (YU Legends Live), a special publication by Rock magazine, 5. april '81 was pronounced one of 12 best Yugoslav live albums.[132]

The Rock Express Top 100 Yugoslav Rock Songs of All Times list features eight songs by Bijelo Dugme: "Lipe cvatu" (polled No.10), "Bitanga i princeza" (polled No.14), "Sve će to, mila moja, prekriti ruzmarin, snjegovi i šaš" (polled No.17), "Sanjao sam noćas da te nemam" (polled No.31), "Ima neka tajna veza" (polled No.38), "Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu" (polled No.68), "Za Esmu" ("For Esma", polled No.78) and "Kad bi' bio bijelo dugme" (polled No.97).[133] The B92 Top 100 Yugoslav songs list features three songs by Bijelo Dugme: "Sve će to, mila moja, prekriti ruzmarin, snjegovi i šaš" (polled No. 14), "Loše vino" (polled No. 32) and "Ako možeš zaboravi (polled No. 51).[134]

The lyrics of 10 songs by the band (8 written by Bregović and 2 witten by Trifunović) were featured in Petar Janjatović's book Pesme bratstva, detinjstva & potomstva: Antologija ex YU rok poezije 1967 - 2007 (Songs of Brotherhood, Childhood & Offspring: Anthology of Ex YU Rock Poetry 1967 – 2007).[135]

In 2016, Serbian weekly news magazine Nedeljnik pronounced Goran Bregović one of 100 People Who Changed Serbia.[136] In 2017, the same magazine pronounced Bijelo Dugme's concert at Hadjučka česma one of 100 Events that Changed Serbia.[137]

In addition to the band's works appearing on various lists of best Yugoslav albums and songs, praised for composition, poetic lyrics of Goran Bregović and Duško Trifunvović, musicianship and production, Bijelo Dugme was often criticized by a part of Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav musicians, critics and audience who believe that the group's blend of rock and Balkan folk music paved the way for the appearance of turbo-folk music in the late 1980s and 1990s.[138][139][140][141] Musicians who criticized Bijelo Dugme's work include Pop Mašina frontman Robert Nemeček,[138] Disciplina Kičme frontman Dušan Kojić "Koja",[138] Partibrejkers frontman Zoran Kostić "Cane",[142] and others. In addition, Bregović was often accused of plagiarism, as a number of critics found similarity between some of his compositions and songs by foreign rock acts.[138][139][141]

Bijelo Dugme's works remain popular in all former Yugoslav republics. They are often viewed as one of the symbols of Yugoslav culture, their songs often featured in various forms of yugo-nostalgia.[141]

Members

|

Past members

|

Touring musicians

|

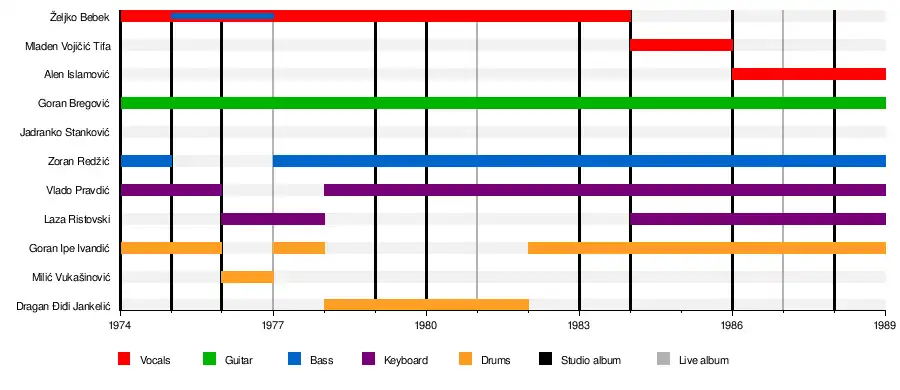

Timeline

Discography

|

Studio albums

|

Live albums

|

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 Janjatović 2007, p. 31.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Vesić 2014, p. 28.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Vesić 2014, p. 32.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 Vesić 2014, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 Vesić 2014, p. 44.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 43.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 48.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 Vesić 2014, p. 47.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 49.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 53.

- 1 2 3 4 Vesić 2014, p. 54.

- ↑ Janjatović 2007, p. 301.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 57.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 58.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 60.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 Janjatović 2007, p. 32.

- ↑ Jurica Pavičić – "Bijelo dugme", Jutarnji list

- ↑ "Bregovićevi uzori opet jašu". Muzika.hr. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 84.

- ↑ "Neil Harrison". Discogs. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Krstulović 2005, p. 27.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 Vesić 2014, p. 88.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 91.

- ↑ Krstulović 2005, p. 28.

- ↑ Glavan, Darko; Vrdoljak, Dražen (1981). Ništa Mudro. Zagreb: Polet rock. p. 12.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 95.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 107.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 195.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 Janjatović 2007, p. 33.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 146.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 133.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 127.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 135.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 137.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 Vesić 2014, p. 152.

- 1 2 Krstulović 2005, p. 32.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 161.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 151.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 164.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 171.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 172.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 173.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 181.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 183.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 184.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 190.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 191.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 192.

- 1 2 3 4 Krstulović 2005, p. 35.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 198.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 Janjatović 2007, p. 34.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 209.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 210.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 218.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 217.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 214.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 227.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 233.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 230.

- ↑ Soldo, Vera (26 December 2018). "Od 'Bijelog dugmeta' do konfekcije" [From the 'White Button' to confection]. Deutsche Welle (in Serbo-Croatian). Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ↑ "Bijelo Dugme – Bijelo Dugme". Discogs. 12 December 1984. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 236.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 245.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 237.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 247.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 248.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 249.

- 1 2 3 4 Vesić 2014, p. 267.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 268.

- ↑ Bubalo, Robert (5 October 2014). "Bregović je želio Vicu Vukova da otpjeva 'Ružicu', ali komunisti nisu dopustili". Večernji list. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 278.

- ↑ "Bijelo Dugme – Mramor, Kamen I Željezo (2xLP, Album) at Discogs". Discogs. 27 March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Janjatović 2007, p. 35.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 280.

- ↑ Krstulović 2005, p. 50.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 285.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 286.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 287.

- 1 2 3 4 Vesić 2014, p. 291.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 292.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 293.

- ↑ "Smrt na estradi". Nedeljnik Vreme. 17 March 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Smrt bubnjara 'Bijelog Dugmeta' i dalje je misterija: bio je osuđen na tri godine zatvora, a onda se desilo nešto što ga je nateralo da skoči sa šestog sprata!", Pulsonline.rs

- ↑ "Izgubljeno dugme… Prošlo je skoro 28 godina, a smrt Ipeta Ivandića i dalje je obavijena velom tajne" Headliner.rs

- 1 2 "BALKAN INFO: Mladen Vojičić Tifa - Ipe Ivandić nije izvršio samoubistvo, on je ubijen!", YouTube

- 1 2 3 "MILIĆ VUKAŠINOVIĆ TVRDI: Ipeta ubila mafija zbog dugova", Novosti.rs

- ↑ Krstulović 2005, p. 110.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 306.

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 307.

- 1 2 3 Vesić 2014, p. 312.

- 1 2 3 Vesić 2014, p. 313.

- ↑ "Koncert Bijelog Dugmeta na Hipodromu, Beograd, 28.06.2005 – dan kada su tate i mame bile neozbiljnije od sinova i ćerki". Ekapija.com. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Popboks – Preminuo Laza Ristovski [s2]". Popboks.com. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- 1 2 Vesić 2014, p. 316.

- ↑ "Stiže limitirano izdanje 'Bijelo dugme – Box set deluxe'", muzika.hr Archived 2014-09-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Vesić 2014, p. 321.

- ↑ "Popboks – JASENKO HOURA – Rock n' roll je velika strast [s2]". Popboks.com. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Popboks – DEJAN CUKIĆ: DOK SE JOŠ SEĆAM... – Sarajevo [s2]". Popboks.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Popboks – SALE VERUDA – Sve što smo govorili i radili bilo je spontano i iskreno [s2]". Popboks.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Dino Merlin: Gnušao sam se dok su ubijali Srbe". Novosti.rs. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Aska (5) – Disco Rock". Discogs. June 1982. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Janjatović 2007, p. 143.

- ↑ "Regina (11) – Ljubav Nije Za Nas". Discogs. 16 September 1991. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Šest ipo tona bombona at Discogs

- ↑ "Прљави Инспектор Блажа & Кљунови* – Игра Рокенрол СР Југославија (Cassette, Album) at Discogs". Discogs. 9 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Viktorija – Ja Znam Da Je Tebi Krivo". Discogs. 16 September 1995. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Vještina at Discogs

- ↑ "Vasko Serafimov – Here". Discogs. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Tragovi u sjeti at Discogs

- ↑ PETROVICPETAR (23 April 2011). "Branimir Štulić svira "MI NISMO SAMI" / "AKO MOŽEŠ ZABORAVI"". YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Bili smo raja at Discog

- ↑ "Texas Flood - Tražim ljude kao ja", Barikada.com

- ↑ "Paraf – Pritanga i vaza". Svastara.com. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "VIDEO Gustafi i Jutarnji.hr predstavljaju nove dvije pjesme 'Moj Tac' i 'Uspavanka' – Jutarnji List". Jutarnji.hr. 7 December 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Rambo Amadeus – Kukuruz za moju bivsu dragu". Svastara.com. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Džoan Baez u BG: Ima neka tajna veza". B92.net. 19 October 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Nirvana kot Bijelo Dugme - Milje (Muggia), Italija - 16.11.1991", YouTube

- ↑ "Rock 'n' roll Zelig". Nedeljnik Vreme. 22 October 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ "Premijera filma "Bijelo dugme"". B92.net. 28 March 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Izgubljeno dugme at IMDb

- ↑ Antonić, Duško; Štrbac, Danilo (1998). YU 100: najbolji albumi jugoslovenske rok i pop muzike. Belgrade: YU Rock Press.

- ↑ Rolling Stone 2015, p. 42.

- ↑ Rolling Stone 2015, p. 62.

- ↑ Rolling Stone 2015, p. 67.

- ↑ Janjatović, Petar; Lokner, Branimir (1987). YU legende uživo. Belgrade: Rock. p. 4.

- ↑ "100 najboljih pesama svih vremena YU rocka". Rock Express (in Serbian). Belgrade (25): 27–28.

- ↑ "Play radio". Playradio.rs. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ↑ Janjatović, Petar (2008). Pesme bratstva, detinjstva & potomstva: Antologija ex YU rok poezije 1967 – 2007. Belgrade: Vega media.

- ↑ Nedeljnik 2016, p. 59.

- ↑ Nedeljnik 2016, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 4 Rosić, Branko (2015). Leksikon YU mitologije. Belgrade; Zagreb: Rende; Postcriptum. p. 180.

- 1 2 "Bosanski rok", Uroš Komlenović, Vreme

- ↑ "Talentovani manipulator ili mnogo više?", Goran Živanović, Rockomotiva.com

- 1 2 3 "I bi rok: 40 godina Bijelog Dugmeta", Balkanrock.com

- ↑ "Cane: Bijelo dugme je obesmislilo rokenrol", Mondo.rs

Sources

- Janjatović, Petar (2007). Ex YU rock enciklopedija 1960 - 2006 (in Serbo-Croatian). Belgrade. ISBN 978-86-905317-1-4. OCLC 447000661.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vesić, Dušan (2014). Bijelo Dugme: Šta bi dao da si na mom mjestu (in Serbo-Croatian). Belgrade: Laguna. ISBN 9788652117031. OCLC 904969157.

- Krstulović, Zvonimir (2005). Bijelo Dugme: Doživjeti stotu (in Serbo-Croatian). Profil International. ISBN 9789531201124. OCLC 163902537.

- "Rolling Stone – Specijalno izdanje: 100 najboljih albuma 1955 – 2015". Rolling Stone (in Serbo-Croatian). No. Special edition. Zagreb: S3 Mediji.

- "100 ljudi koji su promenili Srbiju". Nedeljnik (in Serbo-Croatian). Belgrade (special edition): 59. 2016.