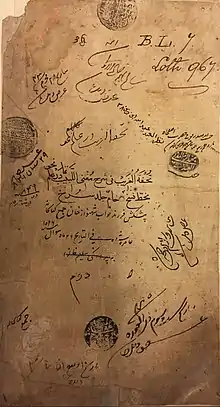

The Bijapur Collection refers to an assemblage of manuscripts held primarily in the India Office collections at the British Library. The manuscripts, in Arabic and Persian, were originally part of the Adil Shahi royal library with many carrying seals of the Adil Shahi rulers.[1] At some point in their history, the manuscripts were removed to the Assur Mahal (اشرمحل).[2] The building was home to a college and theological school founded by Mohammed Adil Shah, Sultan of Bijapur, to house a relic of the Prophet.

In 1848, Bijapur was annexed by the British and the library and institution were found to have no funds for their support. The scholar Charles d'Ochoa visited between 1841 and 1843, and arranged the manuscripts, separating "those preserved from the those utterly destroyed."[3] Items in the Marathi language collected by Ch. d'Ochoa in the Deccan are held in the BnF.[4] Subsequently Henry Bartle Frere, the commissioner of the area, had a catalogue of the Bijapur collection prepared in Urdu by Hamīd al-din Ḥakīm, and that was translated into English by Erskine. Following an examination of the catalogue by one John Wilson, assisted by local scholars, it was decided that the whole collection should be sent to the Court of Directors of the East India Company in London. The manuscripts were dispatched in 1853.[5] Other parts of the Bijapur library went separate ways and are in the Raza Library, Rampur, the Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, St. Petersburg, the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, and the University of St Andrews Library.[6] The India office parts were catalogued, with other Arabic manuscripts from India, by Otto Loth (1844–1881) and published in 1877.[7] After a considerable hiatus, Qureshi provided a summary of the collection in 1980,[8] but no in-depth analysis undertaken until 2016 when Overton examined some of the notations, seals and bindings.[9]

References

- ↑ India Office Records, Selections from the Records of the Bombay Government, N.S., No. 41 (Bombay, 1957): 213-42; for an example, see Muḥammad ibn Ismā'īl al-Bukhārī. Islamic Traditions [120] [Data set]. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4488407.

- ↑ For photograph taken in the 19th century see: https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/photocoll/t/019pho0000125s3u00065000.html

- ↑ Rajeshwari Datta, "The India Office Library: Its History, Resources, and Functions," The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 36, no. 2 (1966): 99-148.

- ↑ S. G. Tulpule, "Un catalogue descriptif des manuscrits marathi dans la collection de Charles d'Ochoa de la Bibliothèque nationale Paris," Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient 75 (1986): 105-123. DOI : https://doi.org/10.3406/befeo.1986.1702.

- ↑ Rajeshwari Datta, "The India Office Library: Its History, Resources, and Functions," The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 36, no. 2 (1966): 143.

- ↑ Examples illustrated in Keelan Overton, "Book Culture, Royal Libraries, and Persianate Painting in Bijapur, circa 1580-1630," Muqarnas 33 (2016): 91-154. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26551683.

- ↑ Otto Loth, A Catalogue of the Arabic Manuscripts in the Library of the India Office (London, 1877), vol. I, Preface, accessible online in https://www.archive.org and in Zenodo at http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3923636.

- ↑ Saleemuddin Qureshi, "The Royal Library of Bijapur," Pakistan Library Bulletin 11, nos. 3–4 (September–December 1980): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5044853.

- ↑ Keelan Overton, "Book Culture, Royal Libraries, and Persianate Painting in Bijapur, circa 1580-1630," Muqarnas 33 (2016): 91-154. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26551683