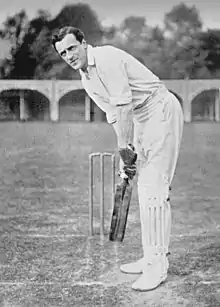

Portrait by George Beldam, c. 1905 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born | 13 October 1877 Bulls Cross, Enfield, Middlesex, England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 12 October 1936 (aged 58) Wykehurst, Ewhurst, Surrey, England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Leg break, googly | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | All-rounder | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut | 11 December 1903 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 5 July 1905 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Domestic team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1898–1900 | Oxford University | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1898–1919 | Middlesex | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: CricketArchive, 17 October 2010 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bernard James Tindal Bosanquet (13 October 1877 – 12 October 1936) was an English cricketer best known for inventing the googly, a delivery designed to deceive the batsman. When bowled, it appears to be a leg break, but after pitching the ball turns in the opposite direction to that which is expected, behaving as an off break instead. Bosanquet, who played first-class cricket for Middlesex between 1898 and 1919, appeared in seven Test matches for England as an all-rounder. He was chosen as a Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1905.

Bosanquet played cricket for Eton College from 1891 to 1896, before gaining his Blue at Oriel College, Oxford. He was a moderately successful batsman who bowled at fast-medium pace for Oxford University between 1898 and 1900. As a student, he made several appearances for Middlesex and achieved a regular place in the county side as an amateur. While playing a tabletop game, Bosanquet devised a new technique for delivering a ball, later named the "googly", which he practised during his time at Oxford. He first used it in cricket matches around 1900, abandoning his faster style of bowling, but it was not until 1903, when he had a successful season with the ball, that his new delivery began to attract attention. Having gone on several minor overseas tours, Bosanquet was selected in 1903–04 for the fully representative Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) tour of Australia.[note 1] During that tour, he made his Test debut for England and although he largely failed as a batsman, he performed well as a bowler and troubled all the opposing batsmen with his googly.

More success followed; in the 1904 season, he took more than 100 wickets and his bowling career peaked when he took eight wickets for 107 runs in the first Test against Australia in 1905 to bowl England to victory. However, he never mastered control of good length bowling and remained an erratic performer. After 1905, Bosanquet's bowling went into decline; he practically gave it up and made fewer first-class appearances owing to his business interests. After taking part in the First World War in the Royal Flying Corps, he married and had a son, Reginald Bosanquet, who later became a television newsreader. He died in 1936, aged 58.

Early life

Bosanquet was born in Bulls Cross, Enfield, Middlesex, on 13 October 1877. He was one of five children of Bernard Tindal Bosanquet and his wife Eva Maude Cotton, daughter of Sir William James Richmond Cotton; Bosanquet had a younger brother and three sisters. His younger brother Nicolas Edmund Tindal Bosanquet also played cricket for Eton. Many of his relations were well known in their fields, including his uncle and namesake Bernard Bosanquet the philosopher.[1][2] His grandfather, James Whatman Bosanquet, was a banker and achieved distinction as a biblical historian. His father worked for the banking firm Bosanquet & Co., and became a partner in a firm of hide, leather, and fur brokers in London; he was also High Sheriff of Middlesex from 1897 to 1898 and captained Enfield cricket club.[3][4] His great-grandfather, Sir Nicolas Conyngham Tindal, was Chief Justice of the Common Pleas between 1829 and 1846.

After going to Sunnymede School in Slough, Bosanquet attended Eton College between 1891 and 1896.[3] While at Eton, he received cricket coaching from the Surrey professionals Maurice Read and Bill Brockwell. They improved his play to the point where he played for the cricket first eleven in 1896.[note 2][1][5] Against Winchester College, he took three wickets and scored 29 not out in the second innings, while at Lord's Cricket Ground against Harrow School, Bosanquet scored 120 runs in 140 minutes.[6][7] At this time, he bowled fast-medium pace, while as a batsman he had developed, in the words of his obituary in The Times, "a rather curious, wristless style; stiff and yet powerful".[1]

Oxford University

In 1897, Bosanquet went to Oriel College, Oxford, and although he left in 1900 without completing a degree, he recorded many sporting accomplishments.[3] Making his first-class debut in 1898 for Oxford University against a team selected by Middlesex captain A. J. Webbe, he had little batting success during the season, having a top score of 17 runs. He was more productive with the ball, twice taking five wickets in an innings for Oxford, and was awarded his cricket Blue. Selected for the University Match, he made 54 not out, his highest score of the season.[6] He later made two appearances for Middlesex,[6] but did not distinguish himself, scoring 17 runs and taking no wickets.[6][8] In all first-class matches in 1898, Bosanquet scored 168 runs at a batting average of 14.00 and took 30 wickets at a bowling average of 18.70.[9][10] At the end of the season, he joined a team led by Plum Warner which toured America, where he had further success as a bowler.[6]

Bosanquet improved his record for Oxford in 1899, scoring two fifties and taking five wickets on three occasions before the University Match. Against Cambridge, he failed with the bat but took seven wickets for 89 runs in the first innings. Bosanquet's record earned him selection for the Gentlemen against the Players; in this prestigious match he took only one wicket but scored 61 runs.[6] He played another two matches for Middlesex and ended the season with a batting record of 419 runs in all matches, at an average of 27.93, and 55 wickets at 22.72.[6][9][10] He played some end of season non-first-class matches for I Zingari, taking 16 wickets in a game against Ireland, and went on another tour of America, led by K. S. Ranjitsinhji.[6]

Bosanquet's final season for Oxford was his best statistically. He scored his maiden first-class century against London County and, against Sussex, he recorded what were to be the best bowling figures of his career, taking nine for 31 in the second innings and a total of 15 wickets in the game for 65 runs. His final match for Oxford was the 1900 University Match, in which he scored 42 and 23.[6] For the remainder of the season, Bosanquet re-joined Middlesex, and in his second match, against Leicestershire, achieved the rare distinction of a century in each innings: 136 in 110 minutes in the first innings, followed by 139 in 170 minutes in the second.[6][11] He scored three further fifties for Middlesex and once took five wickets in an innings, but bowled comparatively rarely, only once bowling more than 13 overs in an innings.[6] In all first-class matches in the season, Bosanquet scored 1,026 runs at 34.20 and took 50 wickets at 23.20.[9][10]

In all his matches for Oxford, Bosanquet scored 801 runs at an average of 25.03 and took 112 wickets at an average of 19.49.[12][13] In other sports, he received half-Blues for hammer-throwing and billiards, and also played ice hockey.[3]

Developing the googly

Genesis

Bosanquet is remembered as the inventor of the googly, a delivery designed to deceive the batsman. When bowled, it appears to be a leg break, but after pitching the ball turns in the opposite direction to that expected, behaving as an off break instead.[1][3] However, Bosanquet was a pace bowler in his university days. Wisden Cricketers' Almanack described his bowling from this period as "very useful ... but that was all, and had he kept to his original style real distinction at cricket would only have come to him through his batting".[14] Furthermore, he disliked bowling quickly, believing he was destined only to be used as a last resort and that he would have little success as a fast bowler.[2][15] Consequently, Bosanquet decided to change his style. According to his own account, his inspiration came in the mid-1890s,[16] from a table-top game he often played called Twisti-Twosti; the object was to bounce a tennis ball on a table so that it could not be caught by an opposing player. Bosanquet began to experiment with ways of throwing the ball so that, after pitching, it turned and spun in an unexpected direction, without his opponent detecting any difference in the delivery.[17] Finding he could do this successfully, he began to practise using the same method to bowl in a form of soft-ball cricket and then in the cricket nets with a hard ball, but did not at the time take his discovery seriously.[15][17] It was not until 1899 or 1900 that Bosanquet began to practise in earnest, and developed an orthodox leg break in the nets to complement his new style of delivery, which spun in the same direction as an off break.[18] During the lunch breaks in Oxford matches, he would often bowl to the best opposing batsmen in the nets, delivering several leg breaks, followed by an off break, without changing his bowling action; the ball would sometimes hit the bemused batsman on the knee, to the amusement of spectators.[17] A slightly different version of events was provided by the son of Louise Bosanquet, Bernard's cousin, who claimed in 1965 that Bosanquet conceived the idea in 1890 and practised bowling to Louise with a tennis ball from 1893 onwards.[19] There were later suggestions that other cricketers invented the googly before Bosanquet. In 1935, Jack Hobbs wrote that Kingsmill Key, a former captain of Surrey, told him that the googly was invented by an Oxford student, Herbert Page, in the 1880s. Key claimed that Page bowled the delivery regularly, but never used it in a first-class match.[20]

Practising throughout 1899 and 1900, Bosanquet began to use the googly in minor matches before using it in important cricket. His first use of the new delivery in first-class cricket came in the match against Leicestershire in 1900 in which he scored two centuries. In the second innings, Samuel Coe had scored 98 when Bosanquet, still known as a fast-bowler, bowled his off break; the ball bounced four times and the batsman was stumped (although, writing in 1925, Bosanquet recalled Coe had been bowled).[11][17][21] Bosanquet later wrote that the wicket "was rightly treated as a joke, and was the subject of ribald comment".[17] Middlesex captains permitted him to try googlies if there was little pressure on, but he later wrote: "Though I could claim some five or six wickets before the close of the season, my efforts produced far more laughter than dismay in the hearts of opposing batsmen".[18] But Bosanquet persisted with the delivery and soon began to be noticed by influential cricketers who recognised the potential of the googly. Previously, some bowlers occasionally bowled unintended googlies, but were unable to control them.[17] Although batsmen were accustomed to off break or leg break bowlers, it was an unprecedented problem to face a bowler who could bowl both types of delivery at will, disguising which one he bowled.[1] Bosanquet persuaded teammates to remain silent as he wished to maintain the impression that his off break was an accident so that batsmen were not expecting it.[17] He further tried to play down his successes: he feigned surprise, acting as if they were similarly accidental.[22]

It was around 1903 that Bosanquet's delivery first became known as a "googly".[1] Pelham Warner claimed that the first use of the word was in the Lyttelton Times, a newspaper based in Canterbury, New Zealand, during a 1902–03 tour, but subsequent research has failed to find it.[23] Some have suggested a Maori origin for the word, although other explanations include a derivation from "guile" meaning cunning, or from the word "googler", meaning a high, flighted delivery at the time.[24]

Regular use in County Cricket

Apart from some early season games for MCC and A. J. Webbe's XI, all of Bosanquet's cricket in 1901 was for Middlesex.[6] He maintained his faster style of bowling but also began to bowl slow leg breaks, with the as-yet unrecognised googly mixed in as variation. Later, he found he could not effectively maintain both styles and decided to concentrate on spin, gradually dropping his quick bowling.[14] His bowling brought him 36 wickets at an average of 37.52 in 1901 but did not take more than three wickets in a single innings.[10] With the bat, it took until July for him to pass fifty runs in an innings but his form improved in August with four fifties. He ended the season with consecutive centuries against Surrey and Essex. In total, Bosanquet scored 1,240 runs at an average of 32.63,[6][9] and Warner regarded him as one of the three most reliable batsmen in the Middlesex side.[8] After the season, Bosanquet went on his third tour of America, captaining a team himself. From January to April 1902, he toured the West Indies with Richard Bennett's team. He scored 623 runs at an average of 34.61 with five fifties and 55 wickets at an average of 15.47, including figures of eight for 30 in one innings.[9][10] Bosanquet's cricket followed a similar pattern in 1902. He scored 749 runs at an average of 24.96, with a century against Cambridge. However, he did not pass fifty after the end of May until his last game of the season.[6][9] With the ball, he took 40 wickets at an average of 21.17. These included 10 wickets against Oxford and 10 against Nottinghamshire;[6][10] the latter performance, when he took seven for 57 in the second innings was described as remarkable by Wisden. It was the first time that his new bowling style attracted attention, although Bosanquet himself tried to play down the success for fear of alerting batsmen to his googly.[14][17]

Controversy in New Zealand

In the winter of 1902–03, Bosanquet took part in another tour, this time with Lord Hawke's team which played matches in New Zealand and Australia and was captained by Warner. In New Zealand, he played two matches against a New Zealand representative side, and in all matches scored 148 runs at an average of 18.50 with one fifty, an innings of 82 against South Island.[6][9] Bosanquet also took 18 wickets at an average of 22.61; his style of bowling attracted a great deal of attention.[10][25] In one game, Charles Bannerman, who played in Australia's first Test match in 1877, was umpire. He told Warner: "When the next team goes to Australia, be sure that Mr Bosanquet is in it. He bowls a lot of bad 'uns; but that ball of his that breaks the wrong way will be very useful on the hard Australian wickets."[26] However, the tour was more notable for an incident in the match against Canterbury. Bosanquet had taken an early wicket in the first innings, but bowled poorly afterwards.[27] He was the fourth bowler used in the second innings and with his third ball, it looked as if he had bowled Walter Pearce behind his legs as he attempted a big hit. However, both umpires were unsighted and the non-striker Arthur Sims, who also had his view obscured, urged Pearce not to leave the middle.[25] The tourists' wicket-keeper, Arthur Whatman, Bosanquet and other English players surrounded the umpire, who decided Pearce was not out. Bosanquet then turned to Sims and said: "You're a nice cheat. I bowled him round his legs. Anybody could see that."[25] Sims responded that there was reasonable doubt, but Whatman began to swear and call him a cheat. Bosanquet later bowled Sims and Canterbury were easily defeated.[25] However, the incident continued to attract attention. The English team were severely criticised in the press and Sims' employers refused to release him for any further matches unless Bosanquet apologised. Bosanquet wrote letters of apology to Sims and to the Canterbury Cricket Association, and Sims later told him to forget about it, but Sims' employers would not let him take part in the remaining games.[25]

The tour moved to Australia and Bosanquet scored fifties against the three states which Hawke's team played, accumulating 168 runs at an average of 33.60.[9][28] As a bowler, he took eight wickets at 42.75.[10] His best bowling performance was to take six for 153 out of a New South Wales total of 463.[6] This included the wicket of Victor Trumper, the leading Australian batsman and one of the best in the world at the time. Bosanquet delivered two conventional leg breaks followed by a googly, later described by Bosanquet as the first bowled in Australia, which bowled Trumper.[29] Many critics were impressed by the wicket-taking potential of googly bowling on hard pitches and Warner later described Bosanquet's bowling as causing a sensation.[28]

Test match bowler

Recognition of the googly

In the English 1903 season, Bosanquet's batting record improved. He scored a century against Oxford in the second match of the season, followed by six for 31 in Oxford's second innings. He went on to score nine fifties, including three in successive innings, in an aggregate of 1,082 runs at an average of 34.90.[6][9] With the ball, he recorded his best wicket haul in a season, taking 63 wickets at an average of 21.00.[9] While this was not seen as a particularly impressive record, Wisden noted that "the batsmen who played against him came to the conclusion that he had immense possibilities."[14] Critics recognised that Bosanquet had developed a new style of bowling. While he could not always control the place the ball would land, making him erratic, several cricketers including Warner believed if he could gain more control, he would become one of the best bowlers in the world.[14] Although his bowling was still developing, and he was still trying to perfect bowling an ordinary leg break as well as master the googly,[30] he took six wickets in consecutive innings against Surrey and Kent, going on to take 10 wickets in the latter match. He also took 12 wickets in a match for Warner's team against a touring side, the Gentlemen of Philadelphia.[6] Bosanquet's contributions helped Middlesex to win the County Championship for the first time.[31] Although no Test matches were played that season, Warner believed that Bosanquet's form would have gained him a place in a representative side.[28] For the first time since 1899, he was selected for the Gentlemen against the Players, although he was unsuccessful.[6]

Bosanquet's performances during the season earned him a place on Warner's team for the first tour of Australia by the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), which was to include Test matches. Warner later wrote that he was accused of selecting Bosanquet out of favouritism as they played on the same county team, and received "a hail of criticism and disapprobation" as a result.[32] Before the tour began, Sussex and England batsman C. B. Fry wrote an open letter to Warner in the Daily Express, stating Warner "must persuade that Bosanquet of yours to practise, practise, practise those funny 'googlies' of his till he is automatically certain of his length. That leg-break of his which breaks from the off might win a test match!"[33]

MCC tour of Australia

Bosanquet was one of the few bowlers in the MCC team not to have some success in the opening two matches of the tour, although he impressed Warner. In addition, he scored 79 runs with the bat in the second game.[6][34] The third match of the tour was against New South Wales; Bosanquet took four for 60, and his googly caused many problems, particularly for Australia's opening batsman Reggie Duff. He continuously defeated the batsmen, maintaining his length effectively through the innings.[6][35] By this stage of the tour, Warner believed that Bosanquet was potentially the best bowler in a strong attack if he could bowl a good length, particularly on hard, fast pitches which normally would favour the batsmen.[36] However, Bosanquet's bowling form remained erratic; in a minor match against a weak side, the opposing captain made a joke about his team's bowling being no worse than Bosanquet's.[37]

Bosanquet played in the first Test against Australia, making his Test debut for England. Australia batted first and recovered from a poor start to score 285 runs; Bosanquet took the wickets of Warwick Armstrong and Syd Gregory with googlies to finish with two for 52 in 13 overs.[6][38] He scored a single run when he batted, out of an English total of 577. In the second innings he bowled 23 overs and took one for 100. The English bowlers came under heavy punishment from the Australian batsmen; Victor Trumper scored an unbeaten 185 and the team reached 485.[6] Bosanquet had Monty Noble stumped, and Warner later wrote that he was in good form with the ball, beating Trumper with a googly and troubling others.[39] England needed to score 194 to win and Bosanquet came to the wicket with 13 needed to win; he scored one run before the winning hit was made.[40] A hand injury forced Bosanquet to miss the second Test.[41] However, with England 2–0 up in the series, he returned for the third Test. On a very good pitch for batting,[42] Bosanquet took three for 95 in an Australian innings of 388, and none of the batsmen were comfortable batting against his googly.[6][43] When England replied, Bosanquet was out for 10 runs, hitting a poor shot as his team were bowled out for 245.[44] In Australia's second innings, Bosanquet bowled badly at first, delivering full tosses and long hops at the end of the third day's play. Next morning, his bowling improved as he established a good length, delivering a spell of seven overs in which he took four wickets for 23 runs, again causing confusion with his googly.[45] He finished the innings with figures of four for 73. However, he failed again with the bat, scoring 10 runs in his second innings as England fell to a heavy defeat.[6]

There followed a break in the series of almost a month as the MCC team played more state teams. In the match against Tasmania, Bosanquet scored 35 and an unbeaten 124 which included eighteen fours and five hits over the boundary.[note 3][47] However, his bowling was poor; Warner wrote that Bosanquet "bowled abominably".[48] Against New South Wales, a team the tourists regarded as the biggest challenge outside of the Test matches,[49] Bosnanquet was very successful. In the first innings, he scored 54 runs in 65 minutes, then took two for 51 with the ball.[6][50] When the MCC batted again, he played an innings which Warner called the best of his career. Unbeaten on 17 at the start of the third day, Bosanquet scored 97 runs in 65 minutes before being dismissed for 114.[51][52] Bosanquet followed this with figures of six for 45, including two wickets bowled by the googly.[6][53]

The fourth Test proved to be the crucial game of the series. England scored 249, of which Bosanquet made 12 before falling to the final ball of the first day, and Australia replied with 131. Bosanquet was required to bowl only two overs. He failed again in the second innings, scoring seven but England reached 210. Australia required 329 to win, which was considered possible on a good pitch; Warner recorded that Australia's batsmen believed their team to be favourites.[6][54] Bosanquet came on to bowl shortly before the tea interval and immediately took the wickets of Clem Hill and Syd Gregory. He went on to take another four wickets, at one point having taken five wickets for 12 runs, to complete figures of six for 51. England won by 157 runs to ensure they could not lose the series, being 3–1 up with one game remaining.[6][55] Australia recorded a consolation victory in favourable conditions for the bowlers in the final Test, and Bosanquet scored 20 runs in the match and bowled four overs without taking a wicket.[6][56] In the final match of the tour, Bosanquet scored 22 and took three for 70 in the first innings, one wicket coming when the batsman gave a catch to the wicketkeeper from a wide ball which bounced three times.[6][57]

In all first-class matches on the tour, Bosanquet scored 587 runs at an average of 36.68 and took 37 wickets at an average of 27.27.[9][10] In Test matches, he took 16 wickets at an average of 25.18 and scored 62 runs at an average of 8.85 with a top-score of 16.[58][59] Following the team's return home, Bosanquet wrote an article giving his impressions of the tour for Wisden.[60] The main Wisden report stated: "Bosanquet's value with the ball cannot be judged from the averages, as on his bad days he is, as everyone knows, one of the most expensive of living bowlers. When he was in form the Australians thought him far more difficult on hard wickets than any of the other bowlers, Clement Hill saying, without any qualification, that his presence in the eleven won the rubber."[61]

The reaction of crowds in Australia was slightly different. According to Justin Parkinson, in his book on the history of English leg spin, they took to "calling Bosanquet 'Elsie', a tribute to the elaborate, supposedly effeminate jumpers he wore."[62] They also named the googly delivery a "Bosie". However, this may have been more than a simple shortening of his name. According to Parkinson, it may have referred to the nickname ("Bosey") of Lord Alfred Douglas who was widely known to have had a homosexual affair, a criminal act at the time, with Oscar Wilde. This remained a topical subject, and the source of humour, in Australia. Parkinson suggests that the anonymous originator of the name "Bosie" for the googly must have been aware of the association. He also notes that the other common term in Australia for the googly was "wrong 'un", which was slang for both "criminal" and "homosexual". Parkinson suggests that these two terms for the googly, the nickname "Elsie", were attempts to "label the whole English ruling class as effete".[63]

1904 season

The 1904 season was Bosanquet's best with bat and ball. Although he made a slow start batting, failing to reach double figures in six of his first nine innings, he was immediately successful with the ball. He took nine for 107 for MCC against the touring South African team and seven for 83 for I Zingari against Gentlemen of England, going on to take 11 wickets in the latter match. Then for Middlesex, he scored 110 in 85 minutes with 16 fours, in a tied match against the South Africans, and 126 in two hours against Surrey including a five and 16 fours.[note 4] In the latter match he also took five for 139.[6][64][65] This preceded his selection for two Gentlemen v Players matches in six days. In the first at Lord's, he scored nine and 22 and took four wickets in the match. At the Oval, he hit 145 in 210 minutes with two fives and 15 fours. After taking two for 97 in the Players' first innings, he took six for 60 in the second to give the Gentlemen their second victory in a week.[66][67] In a loss to Lancashire, the eventual 1904 County Championship winners, Bosanquet took six for 99 for Middlesex and in a drawn game against Yorkshire, who finished second in the table, he scored 141 and took 10 for 248.[6][31] Immediately following the Yorkshire game, Bosanquet took 12 for 240 in a defeat of Nottinghamshire.[6] After a quiet time in the return game against Lancashire, Bosanquet had a run of three consecutive successful matches. In the first, he took six for 75 against Surrey. In a close victory over Kent, he took five for 23 and eight wickets in the match after scoring 80 runs, and he achieved figures of 14 for 190 in a win against Sussex. In an end of season festival game, Bosanquet took five for 89 for the South against the North.[6] In all first-class matches, Bosanquet achieved the double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets: he scored 1,405 runs at an average of 36.02 and took 132 wickets at an average of 21.62, the only time in his career he passed 100 wickets in a season. He accumulated five fifties and four centuries; with the ball he took 10 or more wickets in four matches and had 14 five wicket hauls.[9][10]

His performance in 1904 earned him selection as one of Wisden's Cricketers of the Year; the citation noted he was more likely that any other bowler to dismiss a strong side on a good batting wicket, and no batsmen had deciphered how he bowled the googly. However, it also remarked that "he sends down more bad balls than any other front rank bowler."[14]

1905 season

The Australians toured England in 1905, but Bosanquet played only three games before the first Test. He scored 93 against Nottinghamshire,[6] while against Sussex, he scored centuries in each innings for the second time in his career. His first innings century took 105 minutes and his second took 75 minutes.[68] He also took eight for 53 in the second innings to bowl Middlesex to victory and give him 11 wickets in the game.[6] He became the first player in first-class cricket to score two centuries and take 10 wickets in the same match; only two further players have since achieved the feat, as of 2015.[note 5][69] Bosanquet was selected for the opening Test match, his first such appearance in England. In England's first innings, he assisted in a recovery, making his highest Test score of 27. Australia took a first innings lead, but despite a failure by Bosanquet, England scored 426 for five declared in their second innings. Australia were set 402 to win, which was considered unlikely in the time available so the tourists had to bat until the end of the game to achieve a draw. The pitch remained good for batting and Australia reached 62 without losing a wicket. Subsequently, Bosanquet took five quick wickets, including a good catch from his own bowling to dismiss Hill, to reduce Australia to 100 for five. Although the tourists managed a partial recovery, Bosanquet continued to take wickets. With very little time remaining owing to poor light—if play had stopped, Australia would have achieved a draw—he took the last wicket to fall, giving England a 213-run victory. Bosanquet had taken his best Test figures of eight for 107. Wisden reported: "The Englishmen owed everything to Bosanquet ... He gained nothing from the condition of the ground, the pitch remaining firm and true to the end."[70][71]

After two county matches in which he did little with bat or ball, Bosanquet played in the second Test. However, in his two innings, he scored only six and four not out, and did not bowl in the only innings.[6] After taking 11 wickets for Middlesex against Kent in the only match he played between the Tests, in the third match of the series, Bosanquet scored 20 and 22 not out and took one wicket in the match. This was his final appearance of the series as he was dropped for the final two Tests.[6] Wisden reported that "Bosanquet was a complete disappointment".[72] The almanack also commented in the report on the first Test: "In the first flush of his triumph his place in the England team seemed secure for the whole season, but he never reproduced his form, and dropped out of the eleven after the match at Leeds."[70] This was his final Test. In seven matches for England he scored 147 runs at an average of 13.36 and took 25 wickets at 24.16.[73]

In the remainder of the season, Bosanquet never took more than three wickets in an innings, although he scored a century against Essex and three other fifties. He played for the Gentlemen against the Players scoring 38 and 19 but did not take a wicket in the 17 overs he bowled.[6] In 20 first-class matches, Bosanquet scored 1,198 runs (average 37.43) and took 63 wickets (average 27.77). After this season, he rarely bowled and later stated that he did not bowl the googly after 1905, particularly after one embarrassing attempt to do so in a match at Harrow. In another eight seasons of first-class cricket, he took only 22 wickets.[9][10][17] However, his batting seemed to improve in this time.[3]

Later career

After 1905, Bosanquet played fewer first-class matches owing to his business career, and appeared as a batsman rather than an all-rounder. He played rarely for Middlesex, but usually seemed to make runs despite his lack of practice.[1] He played four matches in 1906. He scored 87 and 101 for Middlesex against Somerset in his first game and took five for 51 against Yorkshire in his second. His good form continued in his third match for Middlesex as he scored two fifties against Essex and he was chosen for the Gentlemen against the Players. Although he did not bowl in that match, he scored 56 in the first innings.[6] In total, he scored 415 runs at 51.87 and took eight wickets at 46.00.[9][10] The following season, he played six matches for Middlesex, took two wickets and scored 358 runs at 35.00 with three fifties.[6][9] Bosanquet played more often in 1908. He made 1,081 runs at an average of 54.05, topping the first-class batting averages.[3][9] He scored centuries for Middlesex against Somerset and Lancashire in addition to five fifties. He represented the Gentlemen v Players twice—at Lord's and in an end of season festival game—without reaching fifty. However, in two other festival games in September, Bosanquet scored a fifty for the South against the North and scored 214, the highest score of his career, for the Rest of England against Yorkshire, the County Champions.[6][31] In the season, he also took 12 wickets at an average of 29.00, although only bowling more than 10 overs in an innings three times, the final wickets of his career.[6][10]

Bosanquet did not appear in first-class cricket again until 1911 when he played two matches in the Scarborough Festival at the end of the season. During the first game, he scored a century in 75 minutes for the Gentlemen against the Players, who had an attack including Sydney Barnes.[6][74] In 1912, he played for Middlesex against the Australians but did not bat or bowl, before appearing in three festival games in August and September.[6] He played twice in 1913, hitting two fifties for L. Robinson's XI against Cambridge University and scoring a third fifty in a match at the end of the season, while in 1914 he appeared for Middlesex against Hampshire in Frank Tarrant’s benefit match and for L. Robinson's XI against Oxford University. After the First World War, Bosanquet made seven appearances in the 1919 season, six of them for Middlesex, scoring three fifties in an aggregate of 335 runs (average 27.91).[6][9] He did not appear again in first-class cricket. He ended his career with 11,696 runs at an average of 33.41 with 21 centuries. With the ball, he took 629 wickets at an average of 23.80.[73] He continued to be successful in a good class of club cricket and in matches at country houses.[1] His son later recalled how he "drifted from one country-house party to the next, tipping the butler on Monday morning, before travelling to his next social-cum-sporting invitation."[75]

Style and technique

After he became a leg break bowler, Bosanquet bowled the ball very slowly and did not look dangerous. However, while still appearing to bowl a leg break, he could deliver an off break which confused the best batsmen in the world and this googly was recognised as a completely new style of delivery.[14][28] He achieved this through dropping his wrist before releasing the ball.[76] The unfamiliarity of this type of bowling increased his effectiveness on the occasions when he could bowl a good length. But he was never a reliable bowler; on other occasions, he bowled long hops and full tosses giving away easy runs.[1][77] Warner noted that Bosanquet had been "described as the 'worst best bowler' in the world".[45]

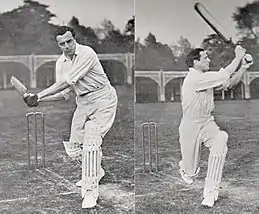

Bosanquet did not bat in a style typical of a cricketer from Eton, where batsmen were taught to play with style and grace.[1] Warner described him as "decidedly stiff and awkward looking ... He does not seem to play the ball in a free, unconstrained way, but rather stabs at it and gives one the impression of making his stroke at the very last moment."[78] In Australia, Bosanquet was troubled by fast pitches and struggled against bowlers such as Monty Noble and Bert Hopkins who could make the ball move towards him through the air.[47] Nevertheless, he displayed great confidence in his ability and on a pitch which assisted spinners, he could flick the ball onto the leg side very effectively.[79] He could hit the ball hard, particularly when driving.[5] The Times said: "He had a wonderful eye and great strength of fore-arm and anything short he could hit very hard."[1]

Personal life and legacy

In the First World War, Bosanquet was a lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps. On 5 April 1924, he married Mary Janet Kennedy-Jones, the daughter of a Member of Parliament. They had one child, Reginald, who later achieved fame as a television newsreader.[3] When his father died, Bosanquet sold the family home, Claysmore, in Middlesex and moved to Wykehurst Farm, Surrey, where he died on 12 October 1936.[3] He left an estate valued at £2,276 0s. 4d (approximately £112,310 or US$129,900 in 2021 terms).[3][80]

As the googly caused a sensation following its invention, many other cricketers tried to emulate Bosanquet.[81] Reggie Schwarz, the South African cricketer who played for Middlesex, learned how to bowl the googly through observation of Bosanquet; Schwarz in turn passed it on to the South African bowlers Aubrey Faulkner, Bert Vogler and Gordon White. These four raised the bowling of the googly to a high standard and raised fears of the detrimental effect it would have on batting.[82][83] Following the development of googly bowling by South Africans, it was further refined by English and Australian cricketers until it became firmly established.[76][84] In later years, the googly was blamed for a deterioration in the quality and attractiveness of batting. Bosanquet refused to accept any blame and published a defence in The Morning Post during 1924, later reprinted in Wisden, which humorously downplayed the impact of the googly.[85] He wrote: "It is not for me to defend it. Other and more capable hands have taken it up and exploited it, and, if blame is to be allotted, let it be on their shoulders. For me is the task of the historian, and if I appear too much in the role of the proud parent, I ask forgiveness."[17]

Until the invention of the googly, bowling was expected to be predictable,[75] and the googly may initially have been considered an underhand tactic.[86] On one occasion, Nottinghamshire batsman William Gunn was stumped after running down the pitch in an attempt to stop a ball bowled by Bosanquet. Gunn's teammate Arthur Shrewsbury then protested that Bosanquet's bowling was unfair.[29] On another occasion, when asked if the googly was illegal, Bosanquet is said to have replied, "Oh no, only immoral."[87] For many years, the googly remained known as a "Bosie" in Australia. His Times obituary stated, "No man probably has in his time had so important and lasting an influence on the game of cricket".[1]

Notes

- ↑ At this time, the MCC organised overseas tours of representative English cricketers. The team was usually named "MCC", but when it played Test matches against another representative side, the team was called "England".

- ↑ "First eleven" means the first team (there are eleven players in a cricket team).

- ↑ In matches in Australia at this time, hits over the boundary were worth five runs. In modern cricket, they would be worth six.[46]

- ↑ In England at the time, the ball had to be hit out of the ground to be worth six and there was no equivalent to the Australian rule for hitting the ball over the boundary for five. Five runs could only be scored from one shot by running.[46]

- ↑ The other two players as of 2015 are George Hirst and Franklyn Stephenson.[69]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Mr B. J. T. Bosanquet". The Times. London. 13 October 1936. p. 21. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- 1 2 Green, p. 176.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Williams, Glenys (2004) [2011]. "Bosanquet, Bernard James Tindal (1877–1936)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/56669. Retrieved 6 October 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ McConnell, Anita (2004) [2011]. "Bosanquet, James Whatman (1804–1877)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2928. Retrieved 6 October 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "Bernard Bosanquet". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1937. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 "Player Oracle BJT Bosanquet". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ "Eton College v Harrow School in 1896". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- 1 2 Warner, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 "First-class Batting and Fielding in Each Season by Bernard Bosanquet". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "First-class Bowling in Each Season by Bernard Bosanquet". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- 1 2 "Middlesex v Leicestershire in 1900". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ "First-class Batting and Fielding For Each Team by Bernard Bosanquet". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ "First-class Bowling For Each Team by Bernard Bosanquet". CricketArchive. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Bernard Bosanquet (Cricketer of the Year)". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1905. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- 1 2 Bosanquet, p. 364.

- ↑ Bosanquet, p. 363.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bosanquet, B. J. T. (1925). "The googly. The scapegoat of cricket". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- 1 2 Bosanquet, p. 365.

- ↑ Green, p. 181.

- ↑ McKinstry, Leo (2011). Jack Hobbs: England's Greatest Cricketer. London: Yellow Jersey Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-224-08329-4.

- ↑ Green, p. 177.

- ↑ Green, p. 178.

- ↑ McConnell, Lynn (5 July 2002). "A case of sledging and abuse of an umpire lost in antiquity". ESPNCricinfo. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ Parkinson, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Williamson, Martin; McConnell, Lynn (11 December 2004). "Bosie, Bannerman and a boycott". ESPNCricinfo. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ Parkinson, p. 29.

- ↑ McConnell, Lynn (8 August 2002). "Sims put his side of 'Bosanquet incident' in autobiography". ESPNCricinfo. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Warner, p. 17.

- 1 2 Green, p. 179.

- ↑ Parkinson, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 "LV County Championship: County Championship Final Positions 1890–2010". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack (2010 ed.). London: John Wisden & Co. May 2010. p. 574. ISBN 978-1-4081-2466-6.

- ↑ Warner, p. 8.

- ↑ Warner, p. 29.

- ↑ Warner, pp. 52, 63.

- ↑ Warner, p. 78.

- ↑ Warner, p. 80.

- ↑ Warner, pp. 90–93.

- ↑ Warner, pp. 106–09.

- ↑ Warner, pp. 127–28.

- ↑ Warner, p. 132.

- ↑ Warner, p. 142.

- ↑ Warner, p. 177.

- ↑ Warner, pp. 178, 181–82.

- ↑ Warner, p. 185.

- 1 2 Warner, p. 190.

- 1 2 Brodribb, Gerald (1995). Next Man In: A Survey of Cricket Laws and Customs. London: Souvenir Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-285-63294-9.

- 1 2 Warner, p. 206.

- ↑ Warner, p. 205.

- ↑ Warner, p. 221.

- ↑ Warner, p. 223.

- ↑ Warner, pp. 224–27.

- ↑ "New South Wales v Marylebone Cricket Club in 1903/04". CricketArchive. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ Warner, p. 228.

- ↑ Warner, p. 261.

- ↑ Warner, p. 262.

- ↑ "Australia v England 1903–04". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1905. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ Warner, p. 298.

- ↑ "Test Batting and Fielding in Each Season by Bernard Bosanquet". CricketArchive. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ "Test Bowling in Each Season by Bernard Bosanquet". CricketArchive. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ Bosanquet, B. J. T. (1905). "MCC in Australia 1903–04: Impressions of the tour". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ "The M.C.C.'s team in Australia, 1903–04". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1905. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ Parkinson, p. 32.

- ↑ Parkinson, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ "Middlesex v South Africans in 1904". CricketArchive. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "Surrey v Middlesex in 1904". CricketArchive. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "Gentlemen v Players in 1904 (Lord's)". CricketArchive. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "Gentlemen v Players in 1904 (The Oval)". CricketArchive. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Green, Benny, ed. (1982). "The County Matches (Middlesex)". Wisden Anthology 1900–1940. London: Queen Anne Press. p. 160. ISBN 0-7472-0706-2.

- 1 2 "Records and Registers: All-round Records". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack (2010 ed.). London: John Wisden & Co. May 2010. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-4081-2466-6.

- 1 2 "England v Australia 1905 (first Test)". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1906. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "England v Australia in 1905". CricketArchive. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ "England v Australia 1905 (third Test)". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1906. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- 1 2 "Bernard Bosanquet Player Profile". ESPNCricinfo. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Swanton, E. W.; Woodcock, John, eds. (1980). Barclay's World of Cricket (2 ed.). London: Collins. p. 143. ISBN 0-00-216349-7.

- 1 2 Mortimer, p. 22.

- 1 2 Frith, p. 161.

- ↑ Warner, p. 106.

- ↑ Warner, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Warner, p. 18.

- ↑ "Inflation calculator". www.bankofengland.co.uk. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ↑ Frith, p. 93.

- ↑ "Reginald Schwarz (Cricketer of the Year)". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. 1908. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Foster, R. E. (1908). "South African bowling". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Wilde, Simon (1999). "The history of mystery". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. London: John Wisden & Co. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ↑ Green, p. 180.

- ↑ Mortimer, p. 23.

- ↑ Thompson, A. A. (1967). Cricketers of My Times. London: Stanley Paul. p. 179. ISBN 0-09-084820-9.

Bibliography

- Bosanquet, B. J. T. (1906). "The off-breaking leg-break". In Beldam, George W.; Fry, Charles B (eds.). Great Bowlers and Fielders: Their Methods at a Glance. London: MacMillan and Co.

- Frith, David (1983) [1978]. The Golden Age of Cricket 1890–1914. Ware, Hertfordshire: Omega Books Ltd. ISBN 0-907853-50-1.

- Green, Benny (1988). A History of Cricket. London: Guild Publishing. OCLC 671855644.

- Mortimer, David (2003). Cricket Clangers: An amusing collection of cricket's most embarrassing moments from over a century. London: Robson Books. ISBN 1-86105-613-3.

- Parkinson, Justin (2015). The Strange Death of English Leg Spin: How Cricket's Finest Art Was Given Away. Durrington, West Sussex: Pitch Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78531-029-4.

- Warner, P.F. (2003) [1904]. How we Recovered the Ashes. An Account of the 1903–04 MCC Tour of Australia (reprinted ed.). London: Methuen Publishing. ISBN 0-413-77399-X.