| Beauregard Castle | |

|---|---|

Château de Beauregard | |

| Chippis, Valais, Switzerland | |

View of the castle ruins | |

Beauregard Castle  Beauregard Castle | |

| Coordinates | 46°16′41″N 7°33′08″E / 46.27806°N 7.55222°E |

| Type | Rock castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Beauregard Castle Foundation[1] |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruins |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Stone masonry |

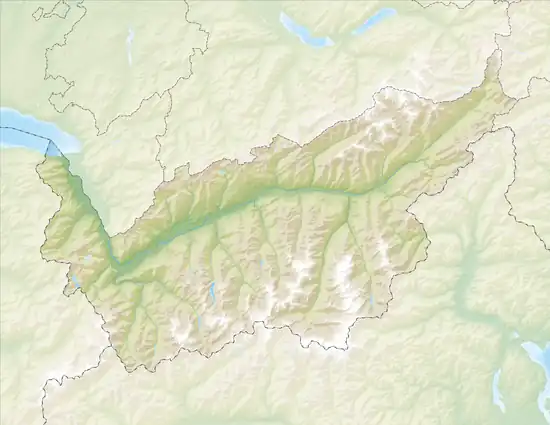

Beauregard Castle (in French "Château de Beauregard") is a ruined castle on the territory of Chippis in the canton of Valais, Switzerland. It is situated on a rocky spur at the entrance to the Val d'Anniviers.

Of unknown origin and use, it belonged to the Raron family in the 14th century. In 1387, the castle was damaged by the soldiers of Amadeus VII in reprisal for an uprising of the Raron against the Bishop of Sion, Edward of Savoy. Thirty years later, it was destroyed in a fire as a result of the Raron affair. Archaeological excavations between 2008 and 2011 have revealed its perimeter and ruins.

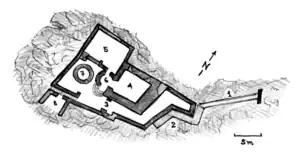

The castle had a dwelling served by a spiral staircase, a tower and a circular cistern unique in Valais, all surrounded by an enclosure. Access from the footpath used to be via a wooden footbridge. Since 2017 it is accessible via a short via ferrata.

Location

.jpg.webp)

Beauregard Castle is located in the municipality of Chippis in the canton of Valais, Switzerland. It is located at the entrance to the Val d'Anniviers, on the right bank of the Navizence, on a rocky spur about 500 metres (1,600 ft) above Chippis and at an elevation of 1,012 metres (3,320 ft).[2] It is accessible from the south, from the village of Niouc. A natural fault, however, isolates it from the path which, in the Middle Ages, was completed by a wooden footbridge.[3] Also known as "l'Imprenable" (in English "the Impregnable"), the castle's location overlooks a panorama of the Rhône valley and part of the Val d'Anniviers.[2][4]

History

Origin

The origin of the Beauregard Castle is uncertain; it was only mentioned twice in the regional archives: on a deed of 1457 under the name "bel regard" and on a map of 1545 under the name "Perigard".[5][6][7] Some historians placed its construction in 1097, but there is no evidence of this.[8] Its architectural style, however, is similar to other castles in the area and suggests that it was built in the eleventh century.[9] It is very likely that it already belonged to the de Raron family before 1380, the year in which Peter of Raron married Beatrice, daughter of James II of Anniviers.[8][10] On the death of the latter, who had no sons, the estate of the Val d'Anniviers first went to Aymon de Challant, Beatrice's first father-in-law, and was then bought by Peter of Raron who was then Count of Sierre, for 1,700 florins.[11] It is possible that the Beauregard Castle was originally owned by the Albi family, the family of Peter of Raron's first wife, who owned the seigneury of Granges, but it could also have belonged to the de la Tour family or to the Knights of Sierre.[12][13] It is certain, however, that the castle was part of the territory of Sierre, since it is situated further north of the "Petra Letzi" rock that delimits Anniviers and Sierre on the right bank of the River Navizence.[12]

What the castle was used for also remains a mystery. It may have been used to defend either the entrance to the Val d'Anniviers or the road on the left bank of the Rhône, but it is also possible that it served as an observation and communication post by means of fires or as a refuge of last resort for its owners.[5]

First assault by the Savoyards

In the 1380s, Peter of Raron led a revolt movement against the new Bishop of Sion, Edward of Savoy who had displeased the people of Valais because of his Savoyard origins, his family being seen as too powerful. Peter of Raron then seized the castles of Tourbillon, Majorie and Soie, all three properties of the episcopal power. Amadeus VII of Savoy, called for help by his relative, went up the Rhône valley with his army and stormed Sion. Once captured, he partially destroyed the city and demanded that the episcopal estates were returned to the bishop. Peter of Raron complied, however, as Edward of Savoy could not move without a Savoyard personal guard, he decided to resign two years later. As the alliance between Peter of Raron and the people of Valais was still problematic, Amadeus VII returned to Valais with a large army in October 1387. This time he stopped off in Salquenen, where peace agreements were concluded with a number of communes in the region, including Leuk.[14]

On the way back, Amadeus VII attacked certain possessions of the Raron family in the Val d'Anniviers.[14] He laid siege to Beauregard Castle while Peter of Raron was there. While a detachment of his men went around the building from the top of the mountain, Amadeus stayed below and massacred the Anniviards who had come to the aid of their lord. Beauregard Castle was finally taken and Peter's sons, Petermann and Heinzmann, were imprisoned and hanged on the Grand-Pont in Sion. The castle was damaged but was quickly restored by the Raron family.[15]

Victim of the Raron affair

At the beginning of the 15th century, the Raron family still occupied an important place in the political life of the Valais: William II of Raron was Bishop of Sion and Witschard of Raron, son of Peter, was Grand Bailiff.[16] In 1414, Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg handed over all sovereignty rights over the Valais to Witschard. The news of these new powers provoked the anger of the Valaisan communes, and brought the Raron affair, a rebellion that brought several cantons of the Swiss Confederation into conflict with each other and threatened a civil war in the Confederation. The Valaisans were therefore in conflict with the entire Raron family.[17]

Between 1416 and 1417, the properties of the Raron family were taken by storm by the Valaisan communes, their house in Sierre and the tower of Loèche being the first to be burnt down. This was followed by a long siege to take Beauregard Castle. The attackers were unable to penetrate the castle, but hunger and thirst finally overcame the defenders, who surrendered. The castle was then burnt down and was never rebuilt. Witschard of Raron was placed in exile before being returned to the lordship of Anniviers in 1420.[18]

Archaeological discoveries and conservation

In 1951, Louis Blondel, a Swiss archaeologist, undertook the first survey of the ruins of Beauregard Castle and concluded that Beauregard was only a watchtower.[19] He also questioned a 15th-century construction, preferring a 12th-century estimate and stating: "[In the 15th century], we were trying ... to get closer to the roads and avoid the inconveniences due to the lack of supplies".[20]

At the beginning of the 21st century, little was known about Beauregard Castle and no archaeological excavations had been carried out on the site. In 2005, Bernard de Preux, a member of the Swiss Heritage Society, proposed the launch of an archaeological investigation in order to learn more about the importance of the site. Three years later, Swiss Heritage and the communes of Chippis and Sierre set up the Beauregard Castle Foundation to raise funds to carry out the excavation work.[1][21]

The first field survey was carried out in 2008 and, once the cantonal authorisations had been obtained, the Beauregard site was cleaned up and the top of the hill was lowered by 9 metres (30 ft). Led by Alessandra Antonini, the archaeological excavations took place from 2009 to 2011 and uncovered a large part of the castle's ruins.[21] The work cost almost 600,000 Swiss francs (equivalent to $845,577 in 2022).[22]

In 2016, the cistern was covered to prevent falls and leaves filling it up, while the spiral staircase was covered with a roof.[23][24] In 2017, an educational path from the village of Niouc was completed. The natural fault can since be crossed by a via ferrata.[25]

The path leading to the castle was completed in 2017.

The path leading to the castle was completed in 2017. Protection placed above the castle's cistern

Protection placed above the castle's cistern The stairwell has also been protected.

The stairwell has also been protected.

Description

Access

Access to the castle was via a 2 metres (6.6 ft) wide and 9 metres (30 ft) long wooden bridge over a moat. On the east side of the path, the footbridge passed over a wall built directly on the rocky spur. This wall also served as the first gate controlling access to the footbridge, similar to the western fortifications of Tourbillon Castle, and was between 3 and 4 metres (9.8 and 13.1 ft) high. The central part of the bridge rested on wooden uprights set into the rock of the moat, while its deck could be dismantled in the event of an attack.[26]

On the castle side, the bridge runs around the rocky spur and ends at the southeast of the enclosure. Notches in the rock along the eastern facade show that the footbridge was supported by horizontal beams. Further notches at the foot of the southern facade of the spur show that there was a first staircase leading to a landing, followed by four further steps ending at the main gate of the castle.[27]

- Access to the castle

View of the castle ruins from the end of the path

View of the castle ruins from the end of the path Walls used for the walkway

Walls used for the walkway

Courtyard

The courtyard of Beauregard Castle is divided into two parts. The first, called the lower courtyard, to the east, was used as a guard house as well as an entrance corridor for the main gate. Its width varies between 1.6 and 3 metres (5.2 and 9.8 ft). The lower courtyard was separated from the upper courtyard by a new gate, probably added after the attack of 1387.[28]

A circular cistern, 2.25 metres (7.4 ft) deep, supplied the castle with water.[29] Because of its style, unique in Valais, the archaeologist Alessandra Antonini described it as "the most beautiful cistern discovered so far in Valais".[29][19] The diameter at its base is 2.10 metres (6.9 ft) – at the neck it is 1.90 metres (6.2 ft) – and its capacity is estimated at 6,000 litres (1,300 imp gal). The bottom of the cistern is made of five slabs of slate schist, while its vertical walls have been built with rauhwacke blocks (variety of Greywacke) cut from the ground, behind which is a watertight inner wall of olive-green clay silt. The neck of the cistern is surrounded by a channel made of rauhwacke blocks. This channel is responsible for discharging the surplus water to the east of the castle; it is possible that a spillway to the west existed, but this part of the cistern has collapsed. The circular cistern is built in an old rectangular cistern. The date of the transformation is not known, but it is probable that the circular cistern already existed in 1387.[30]

To the south-west of the enclosure, a small staircase leads westwards to a rectangular tower measuring three by 5 metres (16 ft). Its lower floor was used as an attic, while the second floor was used to guard the south-western edge. The access staircase continues to the west over a postern. This serves as a secondary access to the castle and leads to a vertiginous path along the south-western edge.[31]

- Courtyard of the castle

Location of the door separating the courtyards

Location of the door separating the courtyards.jpg.webp) Interior of the castle's cistern

Interior of the castle's cistern Ruins of the tower to the south-west of the castle

Ruins of the tower to the south-west of the castle

Main building

The main building was a rectangle measuring eight by 9 metres (30 ft) which served as a dwelling for the castle.[32] On the north side, in the remaining wall, there are two openings, a loophole and an asymmetrical hole 70 centimetres (28 in) lower.[33] The walls were not all the same thickness: the north wall was 1.6 metres (5.2 ft) thick, while the west and east walls were 1.6 and 2.5 metres (5.2 and 8.2 ft) thick respectively. The eastern wall faced the natural moat of the castle and was thus perhaps adorned with a glacis.[34]

The entrance to the dwelling was through the west wall, via the spiral stairwell. The beams of the door sill have left traces on the floor and in the west wall, which were found during archaeological surveys.[34][35] The stairwell did not exist when the castle was built. It also served the upper terrace and the upper floor of the dwelling.[35] A layer of ashes was found in the stairwell and proves that the castle was burnt down.[36]

An intact cannonball was found in 2010 in what was identified as the remains of the beams of the upper floor of the main building. Its position at the time of discovery suggests that it was stored on the upper floor which may therefore have been a defensive platform. The shape of the ball indicates that it should have been used for a bombard.[37]

- Main building of the castle

Exterior view from the north-west

Exterior view from the north-west Interior view from the south-east

Interior view from the south-east Ruin of the east wall

Ruin of the east wall.jpg.webp) Stairwell

Stairwell

Upper terrace

A wooden building divided into two 24-square-metre (260 sq ft) rooms, one on the west and one on the east, was located on the upper terrace. These were respectively accessible from a staircase to the north of the cistern and from the spiral stairwell. This building appeared during the last transformation of the castle. This is evidenced, among other things, by the cut-out in the masonry of the stairwell and the western staircase encroaching on the cistern rim.[38]

The west room was glued to the main building of the castle. Its southern facade was divided by a 30-centimetre-thick (12 in) low wall forming the right-hand foot of the door leading into the stairwell. No traces of substruction were found on the north side, suggesting that the wall was directly on the rocky ground. The eastern hall was probably similar in architecture to the western one, with the exception of its south-western corner, which was more massive as it straddled the level of the upper terrace and the cistern.[38]

To the south-west of the upper terrace is a masonry base measuring 1.6 by 1.4 metres (5 ft 3 in by 4 ft 7 in). Overhanging a natural fault, it served as a latrine. It is possible that its use was reserved for the garrison, as the latrines of the lords were probably on the second floor of the main building, as is the case in the castles of Saxon or Saillon.[39]

- The upper terrace of the castle

Stairs leading to the upper terrace

Stairs leading to the upper terrace Oak in the middle of the upper terrace

Oak in the middle of the upper terrace South-western corner of the upper terrace

South-western corner of the upper terrace Latrine ruins

Latrine ruins

- Views from the upper terrace of the castle

Rhone Valley (towards Sion)

Rhone Valley (towards Sion) Chippis

Chippis.jpg.webp) Sierre and Crans-Montana

Sierre and Crans-Montana

See also

References

- 1 2 "Château de Beauregard – La fondation". chateaubeauregard.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- 1 2 Moret 2019, p. 233.

- ↑ Blondel 1952, p. 161.

- ↑ Bonnard, Jean (10 June 2005). "Réhabiliter l'Imprenable". Le Nouvelliste (in French). p. 30.

- 1 2 "Château de Beauregard – Histoire". chateaubeauregard.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ↑ "Château de Beauregard – Bel Regard". chateaubeauregard.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ↑ "Château de Beauregard – Carte de 1545". chateaubeauregard.ch. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- 1 2 Blondel 1952, p. 162.

- ↑ Moret 2019, p. 238.

- ↑ Zufferey 1927, pp. 294–296.

- ↑ Zufferey 1927, pp. 296–297.

- 1 2 Blondel 1952, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ "Château de Beauregard – Aux Rarognes". chateaubeauregard.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- 1 2 Donnet & Blondel 1963, p. 23.

- ↑ Blondel 1952, p. 164.

- ↑ Donnet & Blondel 1963, p. 24.

- ↑ Donnet & Blondel 1963, p. 63.

- ↑ Blondel 1952, p. 165.

- 1 2

- ↑ Blondel 1952, p. 168.

- 1 2 Cassina, Gaëtan (29 January 2015). "Château de Beauregard – Historique". chateaubeauregard.ch. Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ↑ "Le Château de Beauregard sur les falaises de Niouc bientôt". rhonefm.ch. Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- ↑ "Historique". Eric Papon Architecte (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-25.

- ↑ Antonini, Alessandra; Moret, Jean-Christophe (1 November 2011). "Château de Beauregard : 4ème campagne" (PDF). Travaux, Etudes et Recherches Archéologiques. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ↑ Balmer, Yves (presentator), Favre, Philippe and Cassina, Gaëtan (6 January 2017). Pot, Nicolas (ed.). Le journal du 6.1.2017 (in French). Event occurs at 0:00 to 6:07. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ Moret 2019, pp. 242–243.

- ↑ Moret 2019, pp. 244–245.

- ↑ Moret 2019, pp. 245–246.

- 1 2 Moret 2019, p. 247.

- ↑ Moret 2019, pp. 248–251.

- ↑ Moret 2019, pp. 264–267.

- ↑ "Château de Beauregard". Archéologie Anniviers (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-22.

- ↑ "Château de Beauregard – Archère". chateaubeauregard.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- 1 2 "Château de Beauregard – Le Logis". chateaubeauregard.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- 1 2 "Château de Beauregard – L'escalier en colimaçon". chateaubeauregard.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ↑ "Château de Beauregard – L'incendie". chateaubeauregard.ch (in French). Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- ↑ "Château de Beauregard – Le boulet". chateaubeauregard.ch. Retrieved 2020-10-27.

- 1 2 Moret 2019, pp. 248, 260, 262–263.

- ↑ Moret 2019, pp. 260–261.

Bibliography

- Blondel, Louis (1952). Le château de Beauregard dit l'Imprenable (PDF) (in French). Sion. pp. 161–168.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Donnet, André; Blondel, Louis (1963). Châteaux du Valais (PDF) (in French). Olten: Éditions Walter. p. 295.

- Moret, Jean-Christophe (2019). Le château de Beauregard. Sion: Cahiers de Vallesia.

- Zufferey, Erasme (1927). Le passé du val d'Anniviers (in French). Société d'imprimerie d'Ambilly-Annemasse. p. 406.

External links

- www.chateaubeauregard.ch (in French)

- www.alleburgen.de (in German)

- Beauregard in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.