| Battle of Prairie Grove | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the Frontier | 1st Corps, Trans-Mississippi Army | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| c. 9,000[1] | c. 11,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,203 or 1,251 | 1,317 or 1,483 | ||||||

Prairie Grove Location within Arkansas | |||||||

The Battle of Prairie Grove was a battle of the American Civil War fought on December 7, 1862. While tactically indecisive, the battle secured the Union control of northwestern Arkansas.

A division of Union troops in the Army of the Frontier, commanded by James G. Blunt, was posted in northwestern Arkansas after winning the Battle of Cane Hill on November 28. The 1st Corps, Trans-Mississippi Army, commanded by Thomas C. Hindman moved towards Blunt's division in order to attack while it was isolated. However, Blunt was reinforced by two divisions commanded by Francis J. Herron, leading Hindman to take a defensive position on some high ground known as Prairie Grove. Herron attempted to assault Hindman's lines twice, but both attacks were beaten off with heavy casualties. Hindman responded to the repulse of each of Herron's attacks with unsuccessful counterattacks of his own. Later in the day, Blunt arrived and attacked Hindman's flank. Eventually, both sides disengaged and the fighting reached an inconclusive result. However, the unavailability of reinforcements forced Hindman's army to retreat from the field, giving the Union army a strategic victory and control of northwestern Arkansas.

Union forces reported suffering 1,251 casualties (including 175 dead); Confederate forces reported 1,317 casualties (between 164 and 204 dead). Confederate forces suffered from severe demoralization, and many conscripts deserted. The Confederates had to leave many of their dead on the field, in piles and surrounded with makeshift barriers to keep feral pigs from eating the corpses. Today, a portion of the battlefield is preserved within Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park.

Background

In March 1862, a Confederate army under the command of Earl Van Dorn engaged a Union army led by Samuel Ryan Curtis at the Battle of Pea Ridge in northwestern Arkansas. Curtis' army soundly defeated Van Dorn's.[2] After being defeated at Pea Ridge, Van Dorn and a substantial portion of his army were reassigned across the Mississippi River, effectively ending Confederate control of the region.[3]

Following Pea Ridge, Curtis drove further into Arkansas and planned to attack Memphis, but was ordered by Henry Halleck to send half of his force to Cape Girardeau for transfer to Tennessee. Curtis complied and was forced to abandon his plan, instead heading towards Little Rock, Arkansas.[4] After a defeat in a small action near Searcy, Curtis decided that his supply line was vulnerable, and fell back, eventually reaching Helena.[5]

In September, Curtis was assigned to command the Department of the Missouri, replacing its previous commander, John M. Schofield.[6] Curtis later formed the Army of the Frontier and appointed Schofield to command the new army on October 12.[7] However, on November 20, Schofield was forced to give up command of the army due to medical issues, and command passed to Brigadier General James G. Blunt.[8] At the time of Schofield's relinquishment of command, Blunt's division was in Arkansas, while the rest of the Army of the Frontier was stationed near Wilson's Creek in Missouri, where a battle had been fought the year before.[9]

The Confederate commander in the region, Thomas C. Hindman, had previously commanded the Trans-Mississippi Department, but his firm control of the region led to protests from prominent Arkansas civilians, leading Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States, to relieve Hindman of command and replace him with Theophilus Holmes.[10][11] On August 21, Holmes tasked Hindman with producing an organized army from the Confederate units in the Arkansas region and moving to regain control of Missouri for the Confederacy.[12]

In October, Blunt's force made an incursion into Arkansas, and Hindman sent 2,000 men under Marmaduke's command to intercept Blunt and prevent him from joining the main Union force near Springfield, Missouri. Marmaduke gathered at Cane Hill, a ridge near the Boston Mountains. In response, Blunt marched his troops 35 miles (56 km) in two days, meeting Marmaduke's force near Canehill, Arkansas. In the ensuing Battle of Cane Hill, which took place on November 28, Blunt's 5,000 men defeated Marmaduke's 2,000 in a nine-hour battle.[13][14]

Opposing forces

Union

Brigadier-General

Brigadier-General

James G. Blunt Brigadier-General

Brigadier-General

Francis J. Herron

At the beginning of the Prairie Grove campaign, the Union Army of the Frontier was commanded by Schofield.[15] Schofield's army was divided into three divisions, commanded by Blunt, James Totten, and Herron.[16] Blunt's division was known as the "Kansas Division", as many of the soldiers in the division were from Kansas. The division also contained sizable numbers of African American and Native American soldiers, which made Blunt's division unique among Union units in 1862. Totten's and Herron's divisions were both known as "Missouri Division", and contained men from Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Indiana. The division also contained a regiment of Arkansas cavalrymen who had remained loyal to the Union despite the secession of Arkansas.[17]

Confederate

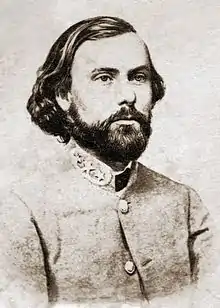

Major-General

Major-General

Thomas C. Hindman

The Confederate army present at Prairie Grove was the 1st Corps, Trans-Mississippi Army, commanded by Hindman.[18] Hindman's command was formed of four divisions: one of cavalry, two of infantry, and a mixed reserve division.[16] The cavalry division consisted of men from Arkansas, Texas, and Confederate Missouri, and was commanded by Marmaduke. Marmaduke's division was poorly armed. Of the army's two infantry divisions, one was commanded by Daniel M. Frost and the other by Francis Shoup. Shoup's division consisted of Arkansas infantrymen, while Frost's division was mostly Missourians, although some Arkansas troops were included. The reserve division was commanded by John S. Roane, and was poorly equipped, organized, and led (Holmes stated that Roane was "useless as a commander"). Of Hindman and his division commanders, all had previous military experience. In particular, Hindman, Frost, and Roane had all seen action in the Mexican War.[19]

Maneuvering to battle

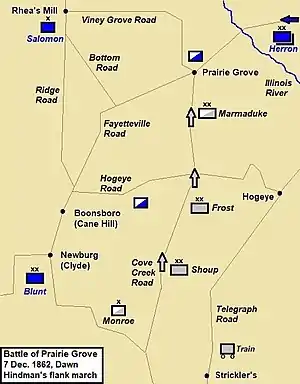

Hindman's offensive

After the Battle of Cane Hill, Hindman decided to send his entire army towards Cane Hill in order to assault Blunt.[20] If all went according to Hindman's plan, he would be able to assault Blunt's position from both the front and along both flanks.[21] At this time, Union forces menaced the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi.[22] On November 11, the Confederate government ordered Holmes to send 10,000 troops to reinforce Vicksburg. Holmes replied that two-thirds of his troops were in northwest Arkansas to oppose a Federal threat. Even so, he ordered Hindman to bring his troops to Little Rock.[23][24] Holmes tried to dissuade Hindman from his plan to attack Blunt and the two generals engaged in an argument over the telegraph. Hindman had a forceful personality and won the argument with Holmes.[25] By December 1, Hindman had gathered between 11,000 and 12,000 troops near Van Buren.[note 1] The Confederate infantry and artillery moved out of their camps on December 3.[26]

Blunt's intelligence services alerted him to Hindman's preparations by the evening of December 2; a courier immediately set out for the telegraph station at Elkhorn Tavern. The messages included a situation report for Curtis in St Louis and an urgent request for Totten to send reinforcements. Blunt prepared to defend himself by posting William Weer's 2nd Brigade and William F. Cloud's 3rd Brigade on high ground south of Newburg with elements of Frederick Salomon's 1st Brigade watching Hogeye Road. A cavalry outpost was set up on Cove Creek Road to watch for Hindman's advance. Every morning from December 3 to 6, Blunt had his troops on the alert, with wagons packed and ready to move quickly.[27]

On November 27, Curtis ordered Totten back to St Louis to be a witness at a court-martial. The unpopular Totten's departure pleased his soldiers and Daniel Huston Jr. assumed command of the 2nd Division. [28] Within a few hours of receiving Blunt's telegraphed call for help, on the morning of December 4, Herron started the 2nd and 3rd divisions on "an epic of human endurance".[18] From the afternoon of December 3 to the morning of December 7, Huston's and Herron's divisions marched 105 and 120 mi (169 and 193 km) respectively. Herron's two divisions averaged 30 mi (48 km) per day over rough roads in intensely cold weather with short stops to eat and sleep.[29] In the early hours of December 6, Herron received a message from Blunt asking for cavalry. Herron promptly dispatched Dudley Wickersham with a 1,600-man provisional cavalry brigade which reached Blunt at 9:00 pm that same day after a 35 mi (56 km) march.[30]

Hindman's new plan

On December 5, Joseph O. Shelby's 1,200-man Confederate cavalry brigade began pressing back the 400 troopers of the 2nd Kansas Volunteer Cavalry Regiment that guarded the Cove Creek Road. Blunt knew that if Hindman continued to use Cove Creek Road, it would be easy for him to cut off the Confederate retreat route. Blunt assumed correctly that Hindman intended to turn to the west and approach Newburg. However, Hindman's plan would change.[31] The bad weather slowed down the march of Hindman's soldiers, so he postponed his planned attack until December 7. He believed that the nearest Union forces were near Springfield, but what he did not know was that Blunt anticipated the Confederate offensive and that Union reinforcements were approaching.[32]

On December 6, near mid-day, the 2nd Kansas Cavalry abandoned its blocking position on Cove Creek Road and withdrew northwest toward Newburg.[32] That afternoon, James C. Monroe's Confederate cavalry brigade, supported by other units, skirmished with the 2nd Kansas Cavalry on Reed's Mountain. By nightfall Monroe's troopers occupied that terrain feature on the road to Newburg.[33] That evening, Hindman and his commanders received startling intelligence that Herron's two divisions would reach Blunt the following day. Hindman realized that attacking Blunt at Newburg would simply push him back toward Herron's reinforcements. The Confederate commander knew that marching back to Van Buren would demoralize his soldiers, so he changed his plan. Hindman's new plan called for the army to march north on Cove Creek Road to Prairie Grove. At that location he would first crush Herron's force, then swing around and smash Blunt.[16] The risk was that Hindman might be caught between the two Union forces if Blunt found out what was happening. At 4:00 am on December 7, the Confederate army began to march north along Cove Creek Road.[34] Shelby's cavalry brigade was in the lead.[35]

Morning clashes

Early on December 7, Marmaduke's 2,000 cavalrymen reached Prairie Grove and discovered 650 Union troopers of the 6th Missouri and 7th Missouri Volunteer Cavalry regiments nearby. Helped by the fact that many Confederates wore captured blue uniforms, Shelby's troopers surprised and routed their opponents, especially the 7th Missouri.[35] The Union 1st Arkansas Cavalry Regiment soon appeared on the Fayetteville Road and was also routed when the Missourians fled through their ranks and Shelby's Confederates charged into them, as was the 6th Missouri and 8th Missouri Cavalry Regiment (Union).[35] The Confederate pursuit continued east past the Illinois River, but ended when it encountered the leading elements of Herron's main column. Shelby was briefly captured, then rescued during a melee with the 1st Missouri Volunteer Cavalry Regiment.[36] During the early morning action, Marmaduke's horsemen inflicted casualties of 10 killed, 19 wounded, and 262 captured on the Union cavalry and seized 21 wagons. Herron's approaching infantry ignored the panicked Union horsemen and its bold front convinced Marmaduke to pull back to the west side of the river.[37]

By the time Frost's 6,300-strong division reached Prairie Grove, Hindman had lost his nerve and set up a defensive line.[35] The Confederate commander might have attacked Herron at once with Frost's powerful division.[35] Fearing that Blunt might intervene, Hindman ordered Frost to face southwest and block the Fayetteville Road. While Hindman waited for Shoup's Arkansas division, Herron had time to push Marmaduke out of his way and reach the Illinois River. When Shoup's 3,200 soldiers arrived at 10:00 am, Shoup assumed a defensive position on the high ground at Prairie Grove.[38] After directing the deployment of Frost's troops, Hindman returned to Prairie Grove. He scolded Shoup for not attacking Herron, but allowed the Arkansas soldiers to remain in position.[39]

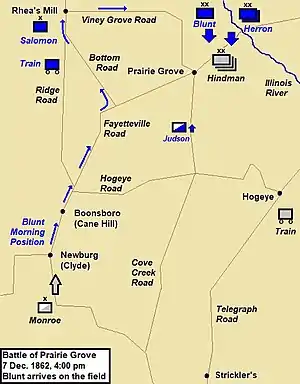

Blunt's march

When Hindman's army started north on Cove Creek Road, Monroe's 400 Confederate horsemen were left at Reed's Mountain to deceive Blunt, while Hindman's main force proceeded against Herron.[40] In the early morning, a Union officer detected Hindman's column marching along the Cove Creek Road. This information was reported to Union headquarters, but Blunt was not there and the critical message was not forwarded for two hours. At about 9:00 am, Blunt was at Newburg expecting to be attacked when he finally realized that Hindman's army was no longer there. By 10:00 am Blunt had gotten his division marching north on Fayetteville Road. Blunt sent William R. Judson with 400 cavalry and two M1841 mountain howitzers up the Cove Creek Road. Judson's column got within 0.5 mi (0.8 km) of Prairie Grove and fired its howitzers for 30 minutes, but withdrew when confronted by superior forces.[41]

Wickersham's provisional cavalry brigade led Blunt's column as it hurried north on the Fayetteville Road. Believing that Rhea's Mill was his destination, Wickersham turned his brigade onto Bottom Road. By the time Blunt realized what had happened, his division was marching toward Rhea's Mill. Wickersham's mistake turned out to Blunt's advantage because it brought his division to the battlefield by the least obstructed route. By 1:00 pm Blunt's division reached Rhea's Mill where the soldiers rested. A half-hour later, Wickersham headed east on the Viney Grove Road toward Prairie Grove where the thunder of cannon was heard. Salomon's brigade stayed at Rhea's Mill guarding the wagon train. By 2:30 pm the infantry followed the cavalry. Since the countryside was flat, the different regiments spontaneously quit the road and set out cross-country at a rapid pace.[42]

Battle

On December 7, the Confederate divisions of Shoup and Marmaduke aligned along the length of Prairie Grove.[43] Later that morning, Herron's Union division reached the field, and, not suspecting that he faced a substantial portion of the Confederate army, opened up an artillery bombardment.[44] Herron was soon joined by Huston's division.[45] Only about 3,500 men, half of the men of the two divisions, were fit to take the field after the grueling march to reach the battlefield.[46] After Herron and Huston had fully deployed their troops, Herron reopened the artillery barrage, which had paused earlier. The Confederate artillery attempted to respond, but their cannons were of inferior quality and lacked the range to properly respond.[46] In addition, the Confederates were also short of artillery ammunition. As a result, the Union gunners were able to wreak havoc in the Confederate line.[47]

Confident after watching the result of the artillery bombardment, Herron sent his two brigades, commanded by Colonel William W. Orme and Lieutenant Colonel Henry Bertram, towards the Confederate line near a farm owned by Archibald Borden.[48][49] Herron's troops made contact with the main Confederate line and the 20th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment and the 19th Iowa Infantry Regiment overran a Confederate artillery battery.[50] However, a counterattack by elements from the brigades of James F. Fagan and Dandridge McRae (both of Shoup's Confederate division) drove off the Wisconsin unit, and brigade commander Bertram was wounded.[51] After the repulse of Bertram's attack, some of Orme's men joined in the fight, only to be driven off.[52] An abortive Confederate counterattack was then driven off by Herron's artillery.[49][53] The two Union regiments that were the hardest engaged—Bertram's 20th Wisconsin and Orme's 19th Iowa—both suffered losses of approximately fifty percent.[54]

After the defeat of Herron's division, Huston deployed some of his men into the fray. The 26th Indiana attacked Marmaduke's Confederate cavalry, and were driven off by a force that included Shelby's brigade and Quantrill's Raiders.[55] Huston ordered the 37th Illinois to charge towards the Borden house, and the Illinois soldiers experienced initial success.[56] However, a Confederate counterattack drove the 37th Illinois back to the main Union line.[57][50] Fagan and Shelby led their men further on towards Herron's main line, and the two brigades were joined by a third under Emmett MacDonald. This attack was also defeated, as the combined fire of Herron's artillery and the survivors of Orme's brigade broke the Confederate assault.[58]

Wickersham's 1,600 Union cavalry reached the battlefield, followed at 3:15 pm by Blunt with his staff and escort. A messenger from Blunt soon alerted Herron that his division was coming. As the news spread, Herron's men gave a cheer.[59] Blunt opened fire on the Confederate army with 30 cannons.[1] Hindman responded by ordering Frost to use his division to counter Blunt. Frost, in turn, sent a brigade commanded by Mosby M. Parsons to the left of Shoup's position. A brigade of dismounted Texas cavalry from Roane's command was also sent to the front, forming to the left of Parsons' brigade.[60] Blunt's forces then prepared to attack the new Confederate left, strengthened by the addition of the 20th Iowa, one of Huston's Union regiments. The 20th Iowa and the First Indian Home Guard assaulted the Confederate line, only to be repulsed. The Confederates responded to the abortive Union assault with another counterattack, using several of McRae's brigade.[61]

Further down the line, Weer's Union brigade began advancing towards Parsons' line. In response, Parsons moved his brigade forward from his original position, creating a confused fight between the two armies' main lines.[62] Eventually, Parsons realized that his line was longer than Weer's, and pushed hard on both flanks of the Union position. Weer was forced to retreat, and Parsons began a counterattack.[63] This attack was driven off by Blunt's massed artillery.[50] As darkness fell, both sides gradually disengaged. While Hindman still held the field, he had no reinforcements and was running out of ammunition.[64] Meanwhile, the Union armies had been reinforced by trailing elements of Herron's command.[49] The Confederate army was forced to withdraw from the field, suffering many losses to desertion in the process.[1] While the fighting was inconclusive, the Confederate withdrawal gave the Union a strategic victory.[1][50]

Aftermath

Union forces reported suffering 1,251 casualties, including 175 dead, 813 wounded, and 263 missing.[35] Confederate forces reported 1,317 casualties, including 164 dead, 817 wounded, and 336 missing.[35][65] The Encyclopedia of Arkansas gives slightly different casualty numbers: 175 killed, 808 wounded, and 250 missing for the Union and 204 killed, 872 wounded, and 407 missing for the Confederates.[50] These reported totals may be too low, as slightly wounded soldiers were not often counted. In addition, Confederate forces suffered from severe demoralization and lost many conscript soldiers during and after the campaign to desertion.[1][66] The Confederates were forced to leave many of their dead on the field, and had to pile the bodies into heaps and surround them with makeshift barriers to keep feral pigs from eating the corpses.[67] The retreat of the Confederate forces from the field gave Union forces control of northwestern Arkansas.[1]

On December 23, Blunt learned that Schofield was on his way to rejoin the army and take overall command. Blunt and Herron decided to attempt one last strike at Hindman's Confederate army before Schofield, who was concerned about the potential of Holmes reinforcing the Confederate's army, arrived.[68] Hindman had made his camp in the vicinity of Van Buren, Arkansas, and Blunt and Herron reached Van Buren on December 29. In the Battle of Van Buren, Blunt's Union forces drove off Hindman's Confederates in disarray, and the remains of the Confederate army left the area.[69][66]

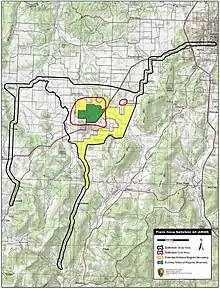

Battlefield preservation

Some of the battlefield area is preserved in Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park, ten miles from Fayetteville, Arkansas.[70] The state park contains over 900 acres (360 ha) of the battlefield.[71] The American Battlefield Trust and its partners have acquired and preserved 351 acres (142 ha) of the battlefield as of mid-2023.[72] The site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.[73]

References

Notes

- ↑ Shea, p. 114 numbers the Confederate force at "roughly" 12,000; yet in the article that Shea wrote about the battle, in Heidler and Heidler, "Encyclopedia of The American Civil War", p. 1558, Shea states the number at 11,000; Josephy, p. 364 states number at "11,300 and 22 cannons"; Eicher, p 392 and Faust, p. 599 state the number at 11,000; Kennedy, p. 148 states c. 11,000; Christ, p. 36 states the number as "approximately" 9,000

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kennedy 1998, p. 143.

- ↑ Christ 2010, pp. 20–22.

- ↑ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 307–308.

- ↑ Shea & Hess 1992, p. 295.

- ↑ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 299–302.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Shea 2009, p. 29.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 4–9.

- ↑ Christ 2010, p. 28.

- ↑ Shea 2009, p. 12.

- ↑ Kennedy 1998, p. 140.

- ↑ Christ 2010, p. 44.

- ↑ Christ 2010, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Eicher 2001, p. 392.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 22–29.

- 1 2 Christ 2010, p. 34.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 85–88.

- ↑ Christ 2010, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Eicher 2001, p. 386.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 448.

- ↑ Josephy 1991, p. 363.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Shea 2009, p. 114.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Shea 2009, p. 72.

- ↑ Shea 2009, p. 128.

- ↑ Shea 2009, p. 131.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 116–117.

- 1 2 Shea 2009, pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 122–124.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 125–127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Eicher 2001, p. 393.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 137–142.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 148–150.

- ↑ Shea 2009, p. 153.

- ↑ Faust 1986, p. 599.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 201–206.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 207–210.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 150–152.

- ↑ Christ 2010, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 155–158.

- 1 2 Shea 2000, p. 1558.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 158–162.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 164–167.

- 1 2 3 Christ 2010, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Montgomery, Don (July 8, 2020). "Prairie Grove, Battle of". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 171–174.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 174–177.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 177–180.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 180–181.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 186–189.

- ↑ Eicher 2001, p. 395.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 190–192.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 193–195.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 210–212.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 215–217.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 219–223.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 225–226.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 233–235.

- ↑ Christ 2010, p. 35-36.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 459.

- 1 2 Christ 2010, p. 36.

- ↑ Shea 2009, p. 244.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 268–269.

- ↑ Shea 2009, pp. 270–281.

- ↑ Shea 2000, p. 1559.

- ↑ "Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park". Arkansas State Parks. Archived from the original on February 5, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ↑ "Prairie Grove Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ↑ "NRHP Inventory Form" (PDF). arkansaspreservation.com. United States Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

Bibliography

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol. 3. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987 [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-571-X. Original edition at the Internet Archive.

- Christ, Mark K. (2010). Civil War Arkansas 1863. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-4087-2.

- Eicher, David J. (2001). The Longest Night, A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster Press. ISBN 978-0-684-84944-7.

- Faust, Patricia L. (1986). Historical Times Illustrated History of the Civil War. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-273116-6.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Josephy, Alvin M. Jr. (1991). The Civil War in the American West. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 978-0-394-56482-1.

- Shea, William L. (2009). Fields of Blood: The Prairie Grove Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3315-5.

- Shea, William L. (2000). "Prairie Grove, Battle of". In Heidler, David S.; Heidler, Jeanne T. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 1558–1559. ISBN 978-0-393-04758-5.

- Shea, William L.; Hess, Earl J. (1992). Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4669-4.

Further reading

- Baxter, William. Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000. ISBN 978-1-55728-591-1.

- Cozzens, Peter. "Hindman's Grand Delusion". Civil War Times Illustrated 39 (October 2000): pp. 28–35, 66–69.

- Hatcher, Richard W., Earl J. Hess, William G. Piston, and William L. Shea. Wilson's Creek, Pea Ridge, and Prairie Grove: A Battlefield Guide, with a Section on Wire Road. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-8032-7366-5.

- Monaghan, Jay (1955). Civil War on the Western Border: 1854–1865. New York: Bonanza Books.