| Battle of Moorefield | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

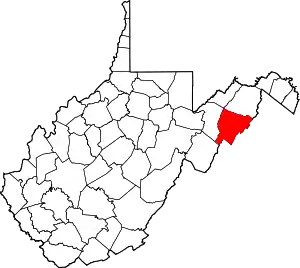

Hardy County, West Virginia, US | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

1st West Virginia Cavalry 2nd West Virginia Cavalry (reserve) 3rd West Virginia Cavalry 1st New York Cavalry 8th Ohio Cavalry 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry |

1st Maryland Cavalry 2nd Maryland Cavalry 36th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry 37th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry 8th Virginia Cavalry 14th Virginia Cavalry 21st Virginia Cavalry 22nd Virginia Cavalry | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,760 | 3,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 42 | 488 | ||||||

The Battle of Moorefield was a cavalry battle in the American Civil War, which took place on August 7, 1864. The fighting occurred along the South Branch of the Potomac River, north of Moorefield, West Virginia, in Hardy County. The National Park Service groups this battle with Early's Washington Raid and operations against the B&O Railroad, and it was the last major battle in the region before General Philip Sheridan took command of Union troops in the Shenandoah Valley. This Union triumph was the third of three major victories (Battle of Droop Mountain, Battle of Rutherford's Farm, and the Battle of Moorefield) for Brigadier General William W. Averell, who performed best when operating on his own.

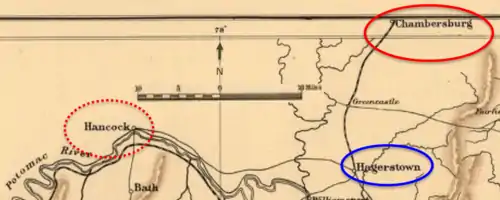

On July 30, Confederate cavalry commanded by Brigadier General John McCausland moved north of the Potomac River and burned most of the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. He then moved west to threaten more towns and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. McCausland was pursued by a smaller cavalry commanded by Averell. McCausland's troops, with fresh horses, were able to escape the Union cavalry and threaten more towns. After re-crossing the Potomac River, McCausland moved south and camped between the West Virginia towns of Moorefield and Romney—closer to Moorefield. He positioned a brigade led by General Bradley Johnson on the north side of the South Branch of the Potomac River, while McCausland's own brigade camped on the south side. Those campsites were better suited for grazing their tired horses than they were for providing for the security of the troops—McCausland assumed that Averell's pursuing force was still 60 miles (97 km) away in Hancock, Maryland. He was correct that Averell had been forced to rest his horses near Hancock, but Averell was reinforced and ordered to continue the pursuit a few days later.

On the night of August 6, Averell's cavalry cautiously moved toward the Confederate camps. Using an advance guard disguised as Confederate soldiers, Averell's cavalry quietly captured all of the Confederate pickets that separated the Union force from the sleeping Confederates. On the early morning of August 7, Averell's first brigade attacked the Confederate brigade camped on the north side of the river. Many of these rebels were sleeping and did not have their horses saddled. In some cases, entire Confederate regiments simply tried to run away, leaving behind weapons and loot taken from Chambersburg. Although the Confederates attempted to offer resistance on the south side of the river that separated the two Confederate camps, many of those men were also caught unprepared. Averell added his second brigade to the fight, and it charged across the river. The disorganized Confederate force was no match for Averell's cavalry, which was armed with sabers, 6-shot revolvers (hand guns) and 7-shot repeating rifles. Over 400 men were either killed or captured, while the Union force lost fewer than 50. Averell's victory inflicted permanent damage on the Confederate cavalry, and it was never again the dominant force it once was in the Shenandoah Valley.

Background

During June and July 1864, Confederate forces under the command of General Jubal A. Early patrolled the Shenandoah Valley. Early's successes were a political liability for President Abraham Lincoln, and caused Union leaders to divert resources away from Richmond and West Virginia.[1] Union soldiers from the Army of West Virginia began arriving via the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in Martinsburg, West Virginia, on July 19, and had an initial success in the Battle of Rutherford's Farm.[2] A few days later, Early tricked Union General George Crook into believing that Early had sent a large part of his Confederate force to Richmond.[3] The result of this deception was a July 24 Confederate victory near Winchester, Virginia, at the Second Battle of Kernstown.[4] Union troops, in some cases panic stricken, retreated to the north side of the Potomac River.[5]

Early, who had threatened the federal capital of Washington, D.C. during the first half of July, followed his Kernstown victory with an attack on northern territory. He dispatched two brigades of cavalry under General John McCausland and General Bradley Johnson to conduct raids in Pennsylvania.[Note 1] McCausland was the force's commander and led the first brigade, while Johnson commanded the second brigade. Their purpose was to burn northern towns unless they received a ransom. Their first two targets were Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and Cumberland, Maryland.[8]

On July 29, McCausland's cavalry force crossed the Potomac River west of Williamsport, Maryland, with the assistance of diversionary crossings at other locations by General John D. Imboden and Colonel William "Mudwall" Jackson.[9] Panic spread throughout the region as McCausland moved toward Chambersburg. The Union troops nearest to McCausland belonged to General William W. Averell, who was stationed in Hagerstown, Maryland, and had troops guarding nearby fords along the river. Averell had only 1,260 men and two pieces of artillery in his command.[Note 2] Averell's communications were cut around noon.[12]

After Early's excursion north of Washington a few weeks earlier, Averell was under pressure to make sure that Washington and Baltimore were not attacked. Averell's spies discovered Confederates moving east on the Baltimore Pike, and Averell mistakenly assumed they planned to attack Baltimore. He cautiously positioned his force, which was under half the size of McCausland's, to protect Baltimore instead of moving directly to Chambersburg. The Confederate troops were merely a patrol that eventually retreated back to Chambersburg. This delayed Averell's arrival at Chambersburg, and allowed the Confederates to raid and burn Chambersburg virtually unopposed on July 30.[13] Damage to the town was devastating—537 homes, businesses, and other structures were destroyed. This included all of the stores and hotels, two mills, two factories, and a brewery.[14] After burning Chambersburg, McCausland moved west and rested his horses. Later that day, Averell arrived in Chambersburg, and then continued to pursue McCausland. His actions may have prevented the burning of Hancock in Maryland, and McConnellsburg and Bedford in Pennsylvania.[15]

McCausland planned to burn Hancock, Maryland, after not receiving a ransom of $50,000 ($765,638 in 2016 dollars). This intensified a rift between McCausland and Johnson, who was from Maryland. Johnson denounced his commander, and ordered some of his men to town to protect its residents. The near-mutiny ended when Averell's cavalry approached.[16] Averell's men skirmished with McCausland's rear guard. McCausland had been able to secure fresh horses, and escaped. Averell's horses were exhausted, and he was forced to pause in his pursuit of McCausland in Hancock. He could not secure fresh horses, since any in the area had already been taken by McCausland.[17] Averell rested his troops until August 3, when he received an order from General David Hunter to pursue McCausland and attack "wherever found".[18][19]

McCausland moves south

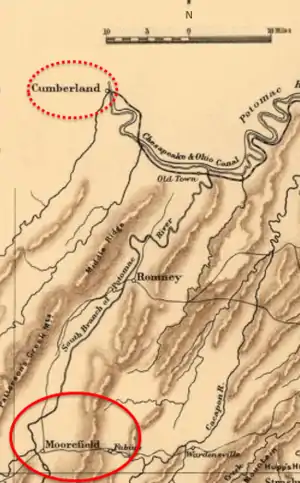

By the time Averell received his order to renew the pursuit of McCausland, the rebels had already threatened Cumberland. McCausland was held off by artillery led by General Benjamin Franklin Kelley.[20] With considerable difficulty, McCausland crossed the Potomac River and made camp near Springfield, West Virginia, on the South Branch River. On the next day, they moved toward Romney, and rested until August 4.[21]

On August 4, the Confederate cavalry continued with their second objective, which was disrupting the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. They attempted to raid New Creek (present day Keyser, West Virginia). General Kelley sent a train load of reinforcements to defend New Creek, which had "well positioned" artillery but a small force.[22] The reinforcements, artillery, and difficult terrain forced the Confederates to retreat south and abandon their raid.[22]

After aborting the raid, the Confederates retreated south towards Moorefield. McCausland believed that Averell was still in Hancock, and was therefore not an immediate threat. He selected camp sites suited for grazing horses instead of defense. Johnson's Brigade occupied the north side of the South Branch Potomac River, while McCausland's Brigade camped on the south shore. The camps were north of Moorefield and south of Romney, along the main north–south road between the two communities and closer to Moorefield. The route back to the Shenandoah Valley was east out of Moorefield along the Wardensville Road, which led to Wardensville and Winchester. McCausland established his headquarters at the Samuel McMechen home in Moorefield, leaving his brigade under the command of Colonel James A. Cochran from the 14th Virginia Cavalry. Horses were unsaddled and fed.[23] Johnson made his headquarters closer to his brigade at a mansion named Willow Wall that was owned by the McNeill family.[24] Each brigade had two pieces of artillery. Johnson kept several groups of pickets north of his camp along the main road.[17] Captain John "Hanse" McNeill, leader of McNeill's Rangers that normally patrolled the area, recommended McCausland reposition the two brigades because he did not believe the camp sites were ideal for the security of the troops. His advice was disregarded, so he moved his Rangers to a more secure site about 8 miles (13 km) away from McCausland.[23]

Renewed pursuit

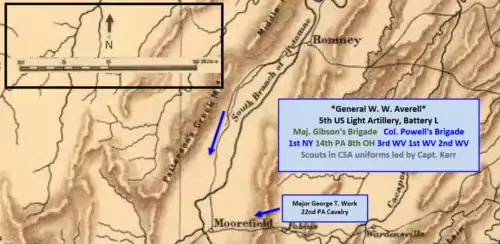

Earlier, while the Confederates attempted to raid New Creek, Averell's force crossed the Potomac at Hancock, Maryland, and headed for Springfield, West Virginia, north of Romney. He was losing horses due to exhaustion, but at Springfield he received food for his men and horses sent by General Kelley. Around this time he learned about McCausland's unsuccessful raid at New Creek, and that McCausland was moving toward Moorefield.[18] He arrived in Romney around 11:00 am on August 6. At that time he sent a battalion of men from the 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry away from the main road to the Wardensville Road. This battalion, led by Major George T. Work, was instructed to block McCausland's route back to the Shenandoah Valley at Lost River Gap while Averell approached from behind, or approach McCausland from the east if fighting had begun. During the afternoon, Averell gathered more information and devised his plan for a surprise attack.[25]

Averell's main force continued southward at 1:00 am on August 7. The force was led by a group of scouts dressed in Confederate uniforms, while the main force followed far enough behind that they could not be detected. The scouts were led by Captain Thomas R. Kerr of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and his men were selected specifically for this mission.[26] While the scouts led the advance, the main body followed at a distance—and had to frequently stop while the scouts made sure it was safe for the main force to proceed. Many of the men would "lie down by the road side, bridle rein in hand, [and] snatch a few minutes of sleep" while waiting for the scouts to signal it was OK to continue.[27] At about 2:30 am, Kerr's scouts deceived and captured a two-man picket from Johnson's Brigade. From this action, the scouts learned the location of the next set of pickets—and quietly captured two more squads of rebels posted along the main road.[27]

Battle

Averell attacks

Averell approached Johnson's Brigade on the main road from the north. Kerr's squad (dressed as confederates) led the advance. Next came Averell's First Brigade (also called the advance brigade), which was commanded by Major Thomas Gibson and consisted of Gibson's 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry and the 8th Ohio Cavalry. Averell's plan was for Gibson's Brigade to attack using their sabers, and to continue to the river. Averell rode with this brigade.[28] Surprise was important for Averell's force, since it was outnumbered approximately 3,000 to 1,760.[29]

The Second Brigade, commanded by Colonel William H. Powell, consisted of three West Virginia cavalry regiments plus the 1st New York (Lincoln) Cavalry (attached). The Lincoln Cavalry detachment, commanded by Captain Abram Jones, rode on the west side of Gibson's Brigade, while Powell and the West Virginians rode on the east side. Powell had the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry in the lead, followed by the 1st West Virginia Cavalry. The 2nd West Virginia Cavalry was held in reserve, and also guarded the pickets that had been captured earlier in the pre-sunrise morning.[Note 3] Powell rode with the 1st West Virginia. Further east, Major Work's 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry battalion was in place on the Wardensville Road and moving west toward Moorefield.[28]

At dawn, Kerr's squad (still dressed as Confederates) casually rode by the First Maryland Cavalry regiment (Confederate), and proceeded west of the road to the McNeill house (Willow Wall) where Johnson made his headquarters. (They were near the tiny community of Old Fields, and sometimes this battle is called the Battle of Oldfields.)[34] No weapons were fired until Kerr reached the house. At that time, Averell's advance brigade, led by Major Gibson, attacked.[35][25] Gibson's advance brigade quickly caused the Confederate 1st Maryland Cavalry, and then the 2nd Maryland Cavalry, to flee "in the wildest confusion" without offering much resistance.[25] Many of the men in the Union cavalry shouted "Remember Chambersburg" as they attacked.[27] About 200 men were captured from the Maryland cavalry units.[36]

Gibson's Brigade continued south, waking the 37th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry. This unit fled in all directions, and Gibson's men did not need to shoot. This left the 36th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, between Gibson's Brigade and General Johnson's headquarters at the McNeill house. The 36th offered the best resistance Gibson had faced so far, but the surprised Confederates were forced to retreat toward the McNeill farm. Near the McNeill house the men from the Confederate Baltimore Battery attempted to fire canister from their two guns, but the unit and guns were captured by the 8th Ohio Cavalry before they could be fired.[36] General Johnson was nearly captured when his headquarters was partially surrounded by Union cavalry. He escaped out the back door and jumped on a horse—racing south to the 8th Virginia Cavalry.[Note 4]

The 8th Virginia Cavalry had enough warning from the commotion that its colonel ordered the men to horse, and they formed a line of battle. After a close fight, the 8th Virginia was overwhelmed and joined other Confederates fleeing to the river. During this fight, Captain Kerr (leader of Averell's advance scouts) was shot in the face and thigh—and his horse was killed.[36] His wounds were not fatal, and he was able to capture the battle flag of the 8th Virginia using his saber. He was eventually awarded the Medal of Honor for his action.[38] General Johnson noted in his report that "Besides the First and Second Maryland and a squadron of the Eighth Virginia there was not a saber in the command."[39] This was a disadvantage in cavalry warfare, and Johnson's men were insufficiently armed for close combat with one-shot muskets. He added that "The long [E]nfield musket once discharged could not be reloaded, and lay helpless before the charging saber."[39]

Colonel William E. Peters was able to get his 21st Virginia Cavalry Regiment ready for the oncoming Union cavalry, but was driven back across the river. Earlier, Peters had refused to burn Chambersburg and General McCausland had him arrested. However, the arrest was revoked a short time later, and Peters led the rear guard when they left the burning town.[40] He performed relatively well at Moorefield, leading portions of his regiment while they slowed the Federal advance on the south side of the river.[Note 5]

At the river

McCausland's Brigade was on the south side of the South Branch of the Potomac River. The 14th Virginia Cavalry, commanded by Captain Edwin E. Bouldin, was the portion of McCausland's Brigade camped closest to the ford where the road crossed the river. Bouldin faced a mob of men crossing the river that consisted of a mix of Union and Confederate soldiers. For a short while, he was able to slow down Gibson's Brigade—which was becoming scattered and disorganized. After hearing the gunfire, Lieutenant Colonel John T. Radford ordered the 22nd Virginia Cavalry into the fray. Radford's cavalry rode to the west side of the 14th Virginia, and joined the fight.[41]

Averell had anticipated resistance at the river, and had Powell's Brigade ready. Major Seymour B. Conger of the 3rd West Virginia Cavalry led the attack across the river on the east side of the main road. On the west side of the road, the Lincoln Cavalry crossed the river unopposed. The New Yorkers circled behind the 22nd Virginia, forcing the regiment to retreat from the riverbank.[41]

Averell's men blamed McCausland for the burning of Chambersburg. In their zeal to get to McCausland's Brigade, they neglected their prisoners who were supposed to be moving north to the rear of Averell's force. This enabled many prisoners from Johnson's Brigade to escape.[42] Among the men who crossed the river were General Johnson and Colonel Peters. After Johnson crossed the river, he "expected to find Brigadier-General McCausland with his command well in hand".[39] However, McCausland was in Moorefield—3 miles (4.8 km) away from his command.[39] Johnson and remnants of the 27th Virginia Battalion joined with Colonel Peters and a large portion of the 21st Virginia behind the camps belonging to McCausland's Brigade. They formed a battle line and fired into Gibson's Brigade, but Gibson was soon reinforced by Conger's regiment. Peters was seriously wounded in the fighting.[41]

Continuing their charge after McCausland's Brigade, the Union cavalry charged into the camp of the 16th Virginia Cavalry, which fled without resisting.[Note 6] Conger's 3rd West Virginia turned eastward and pursued rebels fleeing east down the road to Wardensville and Winchester. The 17th Virginia Cavalry was camped near some woods east of the main road, and had more time to prepare for the attack. They formed a battle line while three companies waited behind a fence. Initially, they repulsed Conger's men, forcing them to retreat.[44] However, Conger was soon reinforced by Colonel Powell and the 1st West Virginia Cavalry, which was commanded by Colonel Henry Capehart. The two regiments charged the Virginians and drove them down the road or into the woods. During this time, Conger was killed by a lieutenant from the 17th Virginia. The Virginian was wearing a blue coat that fooled Conger into thinking he was from Conger's regiment.[44] The two West Virginia regiments continued to pursue the Confederates down the road, and captured McCausland's two pieces of artillery.[45] Eventually, some of the fleeing rebels ran into Major Work's 22nd Pennsylvania, and had to scatter to the woods. Work's men captured 34 of them.[46]

The fighting and pursuit of McCausland's Brigade endured for about 4 miles (6.4 km) until everyone was so scattered that pursuit was useless. Many of the Confederates were afraid of retaliation for their acts in Chambersburg, and did not want to get caught with the money and items they took. This increased their desperation to flee Averell's men, and caused them to leave their loot behind. A considerable amount of money was recovered from the rebel camps.[47]

Aftermath

This battle was the last of the seven battles in Early's campaign against the B&O Railroad.[48] One Union soldier, who was in the battle, estimated that the "loss to the enemy in killed, wounded and captured was near eight hundred".[Note 7] The National Park Service lists estimated Confederate casualties as 500.[34] The final report said that Averell captured 38 officers and 377 enlisted men in addition to killing at least 13 and wounding 60. The Confederate losses to capture might have been higher, but due to the speed of the Union advance many Confederates initially captured were able to escape as they were sent to the rear. The victory cost Averell 11 killed, including 2 officers, 18 wounded, and 13 captured.[29] Those captured were probably stragglers found by McNeill's rangers, who operated in the Moorefield area and chose not to camp with McCausland's brigades.[29]

The ill feelings between Johnson and McCausland continued, and they blamed each other for the defeat. McCausland later wrote "The affair at Moorefield was caused by the surprise of Johnson's brigade."[50] He also wrote that he knew of the approach of Averell, and made the "necessary orders" to confront Averell if necessary.[50] Johnson's report said he followed orders in all instances, including where to make camp and "where to place pickets."[35] His report also noted that McCausland was not with his brigade, and was sleeping 3 miles (4.8 km) away in Moorefield while his "utterly unprepared" brigade was being attacked.[51] Johnson also complained about "the outrageous conduct of the troops on this expedition".[51] He was especially unhappy with the conduct of the Confederate soldiers while in Pennsylvania and Maryland. He reported that "Highway robbery of watches and pocket-books was of ordinary occurrence; the taking of breast-pins, finger-rings, and ear-rings frequently happened. Pillage and sack of private dwellings took place hourly. A soldier of an advance guard robbed of his gold watch the Catholic clergyman of Hancock on his way from church on Sunday...."[51]

Moorefield was another major victory for Averell, who typically did well when operating on his own, but had difficulty with direct supervision where he was expected to work in concert with others. He had already scored victories at Droop Mountain and Rutherford's Farm, and was one of the few Union cavalry leaders that achieved success in the east before the arrival of General Philip Sheridan.[52] Major Stephen P. Halsey of the 21st Virginia described Averell's victory at Moorfield as "one of the most brilliant achievements of the war".[53] Major Theodore F. Lang, from the 6th West Virginia Cavalry, wrote that the "fight was one of the most signal victories for the Union cause during the war".[54]

The devastating loss crippled Early's cavalry in the Shenandoah Valley.[34] It became half the size it was, and had two of its better brigades decimated. The loss also demoralized the remaining members of Early's cavalry.[43] Early later wrote that the battle had "a very damaging effect upon my cavalry for the rest of the campaign."[55] The victory also marked the beginning of the "permanent ascendancy of the Union cavalry in the Shenandoah Valley".[56]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ McCausland was an alumnus of the Virginia Military Institute, which had been burned by Union General David Hunter during June 1864.[6] Johnson and many of his soldiers were from Maryland.[7]

- ↑ Averell's 1st Cavalry Brigade consisted of the 8th Ohio Cavalry and the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry regiments. His 2nd Brigade consisted of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd West Virginia Cavalry regiments.[10] On August 4, 500 additional men from the 1st New York "Lincoln" Cavalry and the 22nd Pennsylvania Cavalry were detached from Brigadier General Alfred N. Duffié's command to assist Averell. This increased his force to 1,760 men.[11]

- ↑ The 2nd West Virginia Cavalry was Powell's original regiment, and he had been its commander. At this time, it was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John J. Hoffman.[30] This regiment may not have been as well armed as other regiments in Averell's command. The 1st West Virginia Cavalry was armed with Spencer repeating rifles during the spring of 1863.[31] Private Joseph Sutton of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry, when complimenting the newly equipped 8th Ohio Cavalry during May 1864 said "we felt littleness compared to that grand body".[32] Sutton described some of the fighting for some of the men from his regiment during the July 1864 Battle of Kernstown as involving "vigorous use of revolver and saber"—no mention of repeating rifles.[33]

- ↑ Historian Scott Pachan's book described Johnson's escape out the house's back door.[36] Averell's report described things differently, saying "General Johnson was captured, with his colors and three of his staff, but, passing undistinguished among other prisoners, effected his escape."[25] Johnson's report said "From the back door of my headquarters, they being around me, I galloped to the Eighth Virginia Cavalry...."[35] At least two other sources say Johnson was captured but escaped, although they do not state if the capture was at the McNeill house or elsewhere later in the battle.[37][16]

- ↑ Johnson's report said Peters "formed and stopped their crossing for some time, with a loss to them, since ascertained, of 2 majors and 38 men."[35] A second source says most of Peters' regiment was captured, but Peters "rallied a squadron of men from the 21st Virginia" and "intermingled with the Federals" on the south side of the river.[36]

- ↑ Averell's report of the Confederate soldiers scattering or fleeing in confusion was not an exaggeration. A Richmond newspaper reporter, who was at the battle, wrote that the two Confederate brigades were "stampeded and routed", and that soldiers were "scattering in wild disorder and confusion and running in different directions".[43]

- ↑ The estimate of 800 casualties was made by private Joseph Sutton of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry.[47] Averell's August 8, 1864, report said "The number of killed and wounded of the enemy is unknown, but large. Three battle-flags were captured, with 4 pieces of artillery (all the enemy had), 420 prisoners, including 6 field and staff and 32 company officers, over 400 horses and equipments, and a number of small arms."[49] General Benjamin F. Kelley's September 17 report said that Averell captured "27 commissioned officers and 393 enlisted men, 4 guns, with limbers and caissons, large quantities of small arms, and 400 horses and equipments."[19]

Citations

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 1

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 138

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 259

- ↑ "Battle Summary: Kernstown, Second". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2017-03-31.

- ↑ United States 1891, p. 324

- ↑ "Hunter's Raid - General David Hunter and the Burning of VMI, June 1864". Virginia Military Institute. Retrieved 2017-02-26.

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 275

- ↑ Pond 1912, p. 100

- ↑ Pond 1912, p. 101

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 330

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 290

- ↑ Pond 1912, p. 102

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 280

- ↑ Bernstein 2011, p. 118

- ↑ Pond 1912, p. 104

- 1 2 Trimpi 2010, p. 137

- 1 2 Sutton 2001, p. 148

- 1 2 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 493

- 1 2 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 3

- ↑ Patchan 2007, pp. 285–286

- ↑ Patchan 2007, pp. 289

- 1 2 Patchan 2007, p. 291

- 1 2 Patchan 2007, p. 292

- ↑ "Moorefield attack 150 years ago "had very damaging effect" on Confederate campaign". Charleston Gazette-Mail. 7 August 2014. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 494

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 296

- 1 2 3 Sutton 2001, p. 149

- 1 2 Patchan 2007, p. 298

- 1 2 3 Snell 2011, p. last page of Chapter 7 in e-book

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 5

- ↑ Lang 1895, p. 164

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 125

- ↑ Sutton 2001, p. 143

- 1 2 3 "Battle Detail - Moorefield". National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2017-01-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 5

- 1 2 3 4 5 Patchan 2007, p. 301

- ↑ Walsh 2002, p. 457

- ↑ "Thomas R. Kerr, United States Army". Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved 2017-04-22.

- 1 2 3 4 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 6

- ↑ Bernstein 2011, p. 117

- 1 2 3 Patchan 2007, p. 303

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 302

- 1 2 Starr 2007, p. 244

- 1 2 Patchan 2007, p. 304

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 305

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 306

- 1 2 Sutton 2001, p. 150

- ↑ "Civil War Battle Summaries by Campaign". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2017-03-26.

- ↑ Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 495

- 1 2 Sutton 2001, p. 153

- 1 2 3 Ainsworth & Kirkley 1902, p. 7

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 119

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 307

- ↑ Lang 1895, p. 200

- ↑ Early 1867, p. 59

- ↑ Patchan 2007, p. 310

References

- Ainsworth, Fred C.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1902). The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Additions and Corrections to Series I Volume XLIII Part 1. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 427057.

- Bernstein, Steven (2011). The Confederacy's Last Northern Offensive: Jubal Early, the Army of the Valley and the Raid on Washington. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-78645-998-8. OCLC 697174428.

- Early, Jubal Anderson (1867). A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence, in the Confederate States of America, Containing an account of the Operations of his Commands in the Years 1864 and 1865. New Orleans: Bielock & Co. OCLC 3278911.

- Lang, Joseph J. (1895). Loyal West Virginia from 1861 to 1865 : With an Introductory Chapter on the Status of Virginia for Thirty Years Prior to the War. Baltimore, MD: Deutsch Publishing Co. OCLC 779093.

- Patchan, Scott C. (2007). Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0700-4. OCLC 122563754.

- Pond, George E. (1912). The Shenandoah Valley in 1864. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 13500039.

- Snell, Mark A. (2011). West Virginia and the Civil War : Mountaineers are Always Free. Charleston, SC: History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-390-9. OCLC 829025932.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (2007). Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071329-1-3. OCLC 153582839.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (2001) [1892]. History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers, During the War of the Rebellion. Huntington, WV: Blue Acorn Press. ISBN 978-0-9628866-5-2. OCLC 263148491.

- Trimpi, Helen P. (2010). Crimson Confederates: Harvard Men Who Fought for the South. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-57233-682-7. OCLC 373058831.

- United States (1891). Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Fifty-First Congress, 1890-'91. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 3888071.

- Walsh, George (2002). Damage Them All You Can: Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. New York: Tom Doherty Associates, LLC. ISBN 978-0-812565-25-6. OCLC 56386619.

External links

Media related to Battle of Moorefield at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Moorefield at Wikimedia Commons