| Battle of Maleme | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Crete | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ (21st, 22nd, 23rd Battalion New Zealand Infantry; 30Sqn & 33Sqn Royal Air Force groundcrew; Cretan Villagers with improvised peasant weapons & gendarmerie) | ~ (one parachute infantry regiment & 100th Mountain Regiment appearing after control of airport) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

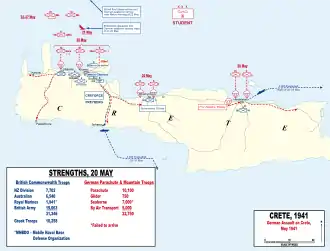

The Battle of Maleme was one of three main battles that occurred in the Battle of Crete against the Fallschirmjäger, in the Nazi German Mediterranean campaign in 1941. The overall plan was to conquer Crete as part of Operation Merkur, with German Paratroopers landing in three main areas, Heraklion, Maleme and Rethymno. The operation relied on German airborne troops, both paratroopers and in military gliders. Due to a mistake, and despite being in a superior position, New Zealand troops abandoned a strategic hill (see below), leaving it to the Germans, and then lost the airport. The airport was then used by the Germans to transport in more troops which saw the whole island lost to the Germans.

Background

Greece became a belligerent in World War II when it was invaded by Italy on 28 October 1940.[1] A British and Commonwealth expeditionary force was sent to support the Greeks which eventually totalled more than 60,000 men.[2] British forces also garrisoned Crete, enabling the Greek Fifth Cretan Division to reinforce the mainland campaign.[3] This arrangement suited the British: Crete could provide the Royal Navy with excellent harbours in the eastern Mediterranean,[4] and the Ploiești oil fields in Romania would be within range of British bombers based on the island. The Italians were repulsed without the aid of the expeditionary force. A German invasion in April 1941 overran mainland Greece and the expeditionary force was withdrawn. By the end of the month, 57,000 Allied troops were evacuated by the Royal Navy. Some were sent to Crete to bolster its garrison, although most had lost their heavy equipment.[5]

The German army high command (Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH)) was preoccupied with the forthcoming invasion of the Soviet Union, and was largely opposed to a German attack on Crete.[6] However, Hitler was concerned about attacks on the Romanian oil fields from Crete[3] and Luftwaffe commanders were enthusiastic about the idea of seizing Crete by an airborne attack.[7] In Directive 31 Hitler asserted that "Crete... will be the operational base from which to carry on the air war in the Eastern Mediterranean, in co-ordination with the situation in North Africa."[8] The directive also stated that the operation was to take place in May[9] and must not be allowed to interfere with the planned campaign against the Soviet Union.[9]

Opposing forces

Allies

No Royal Air Force (RAF) units were based permanently at Crete until April 1941, but airfield construction had begun, radar sites built and stores delivered.[10] On 30 April 1941 Major-General Bernard Freyberg, who had been evacuated from Greece with the 2nd New Zealand Division, was appointed commander-in-chief on Crete. He noted the acute lack of heavy weapons, equipment, supplies and communication facilities.[11][12] Equipment was scarce in the Mediterranean, especially in the backwater of Crete. The British forces had seven commanders in seven months. By early April, airfields at Maleme and Heraklion and the landing strip at Rethymno, all on the north coast, were ready and another strip at Pediada-Kastelli was nearly finished.[10] The Allies had a total of 42,000 men available. Of these, 10,000 were Greek and 32,000 Commonwealth;[13] 27,000 Commonwealth troops had arrived from Greece within a week,[14] many lacking any equipment other than their personal weapons, or not even those; 18,000 of these remained when the battle commenced.[15]

Germans

The design of the German parachutes and the mechanism for opening them imposed operational constraints on the paratroopers. The static lines, which automatically opened the parachutes as the men jumped from the aircraft, were easily fouled, and so each man wore a coverall over all of their webbing and equipment. This precluded their jumping with any weapon larger than a pistol or a grenade. Rifles, automatic weapons, mortars, ammunition, food and water were dropped in separate containers and until and unless the paratroopers reached them they were helpless.[16]

German paratroopers were also required to leap headfirst from their aircraft, and so were trained to land on all fours – rather than the usually recommended feet together, knees-bent posture – which resulted in a high incidence of wrist injuries.[17] Once out of the plane German paratroopers were unable to control their fall or to influence where they landed. Given the importance of landing close to one of the weapons containers, doctrine required jumps to take place from no higher than 400 feet (120 m) and in winds no stronger than 14 mph (23 km/h). The transport aircraft had to fly straight, low and slowly, making them an easy target for any ground fire.[18]

The German airborne forces utilised assault gliders, the DFS 230,[19] which could carry a load of 2,800 pounds (1,300 kg) or nine soldiers and their weapons.[20] They could glide up to fifty miles after release and land very close to a target.[21] Fifty-three in total were used in the attack on Crete.[19] Paratroopers were carried and gliders towed by the reliable, tri-motored, Junkers Ju 52. Each plane could tow one glider or carry thirteen paratroopers. In the latter case their weapons containers were carried in the planes' external bomb racks.[21]

The entire assault on Crete was code named "Operation Mercury" (Unternehmen Merkur) and was controlled by the 12th Army commanded by Field Marshal Wilhelm List. The German 8th Air Corps (VIII Fliegerkorps) provided close air support; it was equipped with 570 combat aircraft. The infantry available for the assault were the German 7th Air Division, with the Air-landing Assault Regiment (Luftlande-Sturm-Regiment) attached, and the 5th Mountain Division. They totalled 22,000 men grouped under the 11th Air Corps (XI Fliegerkorps) which was commanded by Lieutenant General Kurt Student who was in operational control of the operation. Over 500 Ju 52s were assembled to transport them. Student planned a series of four parachute assaults against Allied facilities on the north coast of Crete by the 7th Air Division, which would then be reinforced by the 5th Mountain Division, part transported by air, and part by sea; the latter would also ferry much of the heavy equipment.[22]

Before the invasion, the Germans conducted a bombing campaign to establish air superiority and forced the RAF to rebase its aircraft in Alexandria.[23] A few days before the attack, German commanders were informed unequivocally that the total Allied force on Crete was 5,000 men.[24]

Initial phase

The initial phase of the operation began on May 20, 1941. The Germans used gliders at Maleme, with the intention of landing the troops in the gliders to initially gain control of the ground, and then the bulk of the troops and heavier equipment would be brought in using the Junkers 52 transport planes landing at Maleme airport. Gliders were launched from their towing transport plane offshore with the Germans intent on keeping the transport planes away from the anti-aircraft positions on the Island. Maleme was particularly dangerous to planes as the Maleme airport was heavily defended by anti-aircraft guns.[25]

At around 8 am of the morning of 20 May, gliders appeared in the sky over Maleme. This was followed up by German transport planes that began emptying paratroopers and supply canisters. This was West Group under the code-name "Comet", commanded by German paratroop general Eugen Meindl. The allied forces in the area were the 21st, 22nd and the 23rd battalions of the New Zealand Army, based at the Maleme airport and surrounding areas.[26] The defending New Zealanders started firing at them, and there were heavy losses for the Germans, with many paratroopers killed before they hit the ground. Cretan civilians started attacking the landing troops with improvised peasant weapons, including shotguns, axes and spades. About 50 gliders landed in the dry riverbed, where resistance was less, however paratroopers landed to the South and East of Maleme and were largely destroyed by New Zealand forces that were in positions there [27] In the initial landing, the Germans casualties were immense, one regiment lost 112 out of 126 men, and III battalion lost 400 out of 600 men on the first day.[28]

The initial landing of the gliders was successful, with them landing in the Tavronitis River.[29]

The German soldiers dug in, but were doggedly resisted by New Zealand troops, who were in possession of the strategic Hill 107.[30] The main New Zealand unit at Maleme was the 22nd Battalion, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Andrew. His unit maintained Hill 109 and the western edges of the airport. The battalion persisted engaging the Germans, and Andrew requested support from the 23rd battalion. The support was refused, under the mistaken believe that the 23rd Battalion was engaged in combat when in fact, it wasn't. Andrew decided to try to drive the Germans back from the edge of the airfield, but the two tanks he used in the assault broke down, and the assault faltered.[31]

New Zealand withdrawal from Hill 107

However, though the New Zealand units were convinced they were winning, and the Germans thought they were lost, Andrew decided to retreat from Hill 107, and join up his forces with the 21st Battalion. This he did on the night of 20 May [32] This was an error. Andrew had asked for support, but the nearby units were not given permission to move up to support him, in the incorrect belief they were engaged. They were in fact not deployed, unengaged and waiting for orders, and free to assist. The Germans on the other hand, were in a bad position strategically, and in addition, were only armed with small arms and grenades, as no heavy equipment had come in on the gliders. The Germans themselves were expecting to be overrun by the New Zealand troops the next day.[33] When the Germans saw the New Zealanders move off the strategic position of the hill, they moved to occupy it.[34] There were two other New Zealand units on the edge of the airfield. When they saw their comrades had retreated from the hill area, they retreated as well.[35] The Germans took the vacated hill position, though they only had small arms and were low in numbers. The New Zealanders did not immediately counterattack the hill. This was a decisive event. The Luftwaffe also played a part, attacking ground forces around the hill, with Stuka attacks on the allied troops.[36]

At this point, the Germans started landing transport planes on the airfield. With the Germans now in control of the hill overlooking the landing strip, Luftwaffe Junkers Ju 52 transport planes could then land, and by 5pm the entire town of Maleme was then captured. By this time, the entire 100th Mountain Regiment, under the command of Colonel Willibald Utz, had landed. However, in landing the planes on the airstrip enduring hostile fire, the cost to the Germans was huge; one in three transport planes were destroyed, a total of eight planes. The landing strip was strewn with destroyed planes.[37]

Allied counter attack

Though the New Zealand troops attacked the planes as they landed, enough troops came off the remaining planes to enable the Germans to reinforce the troops that had landed previously. On the night of the 21st, the Allied forces realised the importance of the airfield, and they started to organise a counter attack. two battalions moved to attack it, in an attempt to get it back under control. However, by this time, the 100th Mountain regiment had landed fully deployed, and were dug in; the attempts to take it failed.[38] Another abortive attempt was made to regain the airstrip on 22 May. It reached the edge of the airfield by 7.30 in the morning of that day, but could proceed no further, and was forced to withdraw. [39] [40]

Final capture of Maleme and German move out

With the Germans now in control of the airport at Maleme, they could continue to land more troops and equipment, and started to get the overall advantage in equipment and numbers. The Allied forces withdrew from the area, to Galatos, as they were in danger of being outflanked.[41] At this point, with Maleme under control, the German troops started moving out from Maleme to join up with the other German troops at the other objectives. Although the Allies had been holding off the Germans at the other two objectives, Heraklion and Rethymno, with German reinforcements arriving steadily via the Maleme airport, the tide turned in the favour of the German forces and the whole of Crete was lost.[42]

Citations and sources

Citations

- ↑ Long 1953, p. 203.

- ↑ Long 1953, pp. 182–183.

- 1 2 Beevor 1991, p. 11.

- ↑ Murfett 2008, p. 114.

- ↑ Long 1953, p. 205.

- ↑ Pack 1973, p. 21.

- ↑ Spencer 1962, p. 95.

- ↑ Brown 2002, pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 Schreiber, Stegemann & Vogel 1995, pp. 530–531.

- 1 2 Richards 1974, pp. 324–325.

- ↑ Prekatsounakis 2017, p. ix.

- ↑ Falvey 1993, p. 119.

- ↑ Davin 1953, p. 480.

- ↑ Beevor 1991, pp. 32, 50–51.

- ↑ MacDonald 1995, p. 147.

- ↑ MacDonald 1995, p. 21.

- ↑ MacDonald 1995, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ MacDonald 1995, p. 20.

- 1 2 Kay & Smith 2002, p. 60.

- ↑ Mrazek 2011, p. 287.

- 1 2 MacDonald 1995, p. 17.

- ↑ Beevor 1991, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Vick 1995, p. 27.

- ↑ Beevor 1991, p. 42.

- ↑ "maleme-bridge-crete-german-glider-airborne-forces" http://www.operation-ladbroke.com/maleme-bridge-crete-german-glider-airborne-forces/

- ↑ Thimianos, Giannis "The first day of the Battle of Crete" Fabulous Crete.com

- ↑ "The Battle for Crete - Day 1 - The Battle of Maleme" https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/the-battle-for-crete/the-battle-day-1-3

- ↑ Thimianos, Giannis "The First Day of the Battle of Crete" Fabulous Crete.com

- ↑ "maleme-bridge-crete-german-glider-airborne-forces" http://www.operation-ladbroke.com/maleme-bridge-crete-german-glider-airborne-forces/

- ↑ "maleme-bridge-crete-german-glider-airborne-forces" http://www.operation-ladbroke.com/maleme-bridge-crete-german-glider-airborne-forces/

- ↑ "The Battle for Crete - Day 1 - The Battle of Maleme" https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/the-battle-for-crete/the-battle-day-1-3

- ↑ Bell, Rachael "Evidence and Interpretation in New Zealand’s Official History: The Battle for Crete, May 1941" War in History2015, Vol. 22(3) p371

- ↑ Bell, Rachael "Evidence and Interpretation in New Zealand’s Official History: The Battle for Crete, May 1941" War in History2015, Vol. 22(3) p366

- ↑ Bell, Rachael "Evidence and Interpretation in New Zealand’s Official History: The Battle for Crete, May 1941" War in History2015, Vol. 22(3) p366

- ↑ "The Battle for Crete - Day 1 - The Battle of Maleme" https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/the-battle-for-crete/the-battle-day-1-3

- ↑ "maleme-bridge-crete-german-glider-airborne-forces" http://www.operation-ladbroke.com/maleme-bridge-crete-german-glider-airborne-forces/

- ↑ Mitcham, Samuel "Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in World War II" Stackpole books 2007 p 122

- ↑ Maleme http://www.hellenicfoundation.com/Maleme.htm Archived 2013-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Bell, Rachael "Evidence and Interpretation in New Zealand’s Official History: The Battle for Crete, May 1941" War in History2015, Vol. 22(3) p371

- ↑ Peter Ansil "Crete 1941: Germany’s lightning airborne assault" Bloomsbury p 15

- ↑ Peter Ansil "Crete 1941: Germany’s lightning airborne assault" Bloomsbury p 15

- ↑ Bell, Rachael "Evidence and Interpretation in New Zealand’s Official History: The Battle for Crete, May 1941" War in History2015, Vol. 22(3) p371

Sources

- Brown, David (2002). The Royal Navy and the Mediterranean: November 1940 – December 1941. Whitehall Histories. Vol. II. London: Whitehall History in association with Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-5205-4.

- Beevor, Antony (1991). Crete: The Battle and the Resistance. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-4857-4.

- Bell, A. T. J. (1991). "The Battle for Crete – The Tragic Truth". Australian Defence Force Journal. 88 (May–June): 15–18. ISSN 1320-2545.

- Davin, Daniel Marcus (1953). Crete. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945. Wellington: Historical Publications Branch, Department of Internal Affairs, Government of New Zealand. OCLC 1252361.

- Falvey, Denis (1993). "The Battle for Crete—Myth and Reality". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 71 (286): 119–126. JSTOR 44224765.

- Kay, Antony L.; Smith, John R. (2002). German Aircraft of the Second World War. London: Putnam. ISBN 978-0-85177-920-1.

- Long, Gavin (1953). Greece, Crete and Syria. Australia in the war of 1939–1945. Vol. 2. Canberra: Canberra Australian War Memorial. OCLC 251302540.

- MacDonald, Callum (1995). The Lost Battle: Crete 1941. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-61675-8.

- Mrazek, James E. (2011). Airborne Combat: The Glider War/Fighting Gliders of WWII. Stackpole military history series. Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-4466-9.

- Murfett, Malcolm H. (2008). Naval Warfare 1919–1945: An Operational History of the Volatile War at Sea. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-45804-7.

- Pack, S.W.C. (1973). The Battle for Crete. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-810-1.

- Prekatsounakis, Yannis (2017). The Battle for Heraklion. Crete 1941: the Campaign Revealed Through Allied and Axis Accounts. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-913336-01-1.

- Richards, Denis (1974) [1953]. Royal Air Force 1939–1945: The Fight at Odds. Vol. I (paperback (online) ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-771592-9. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Schreiber, Gerhard; Stegemann, Bernd; Vogel, Detlef (1995). Germany and the Second World War: The Mediterranean, South-east Europe, and North Africa, 1939–1941. Vol. III. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822884-4.

- Vick, Alan (1995). Snakes in the Eagle's Nest: A History of Ground Attacks on Air Bases. Santa Monica: Rand Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-1629-4.

External links

- Warfare History Network - Mishap at Maleme https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/2019/01/14/mishap-at-maleme/