The Ballochmyle cup and ring marks were first recorded at Ballochmyle (NS 5107 2552), Mauchline, East Ayrshire, Scotland in 1986,[1] very unusually carved on a vertical red sandstone cliff face, forming one of the most extensive areas of such carvings as yet found in Britain.[2] They have been designated a scheduled monument.[3]

Discovery

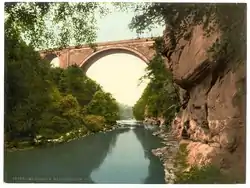

These carvings or petroglyphs were first recorded in 1986 (although a '1751' carved date suggests an earlier discovery) when the Kingencleugh Estate decided to clear an area of vegetation along the north side of the Liddell Burn that is a minor tributary stream of the River Ayr in an area famous for its quarrying of red sandstone. The removal of vegetation exposed the carvings that are distributed across two faces of a vertical outcrop of rock and they were reported to the Dick Institute in Kilmarnock.[4] The presence of possible medieval carvings, the extensive quarrying with numerous workmen employed in the area, especially during the construction of the Ballochmyle Viaduct, emphasises how surprising it is that these glyphs were overlooked for so long, especially as they are only about 2 km south-east of Mauchline's town centre.[5]

Description

The rock here is described as being a "pink dessert sandstone from the Permian age showing clear signs of dune bedding".[6] The cup and ring marks are composed of two 'panels' with several hundred 'cup and ring' and other glyphs or carvings in a range of styles, ranging from single shallow cups through to deeper cups with multiple rings. Less common, but unique in the Scottish context are ‘square with cup’ carvings; ‘ringed stars’ are also present. Three deer-like carvings and some other inscriptions with Lombardic style letters[7] were also carved into the rockface and these are thought to be medieval in date.[8]

Several feet of soil were removed from the bottom of the corner that divides the two main halves of the site and this uncovered three 'trilithon-like' carvings[9][10] and others may await discovery where the soil has not been removed. The carvings were protected by the vegetation and began to deteriorate after this was removed and in addition vandalism and theft of a panel has taken place.[11] It is likely that they were historically hidden from direct view by trees and shrubs.

The Ballochmyle glyphs or motifs are carved on red sandstone, however they are found elsewhere on other sedimentary rocks such as Millstone Grits, as well as the harder igneous and metamorphic rocks such as granites and schists.[12]

Concentric circles and cups.

Concentric circles and cups. An area where 'cups' dominate.

An area where 'cups' dominate. It is unusual to find these glyphs on a vertical rock face.

It is unusual to find these glyphs on a vertical rock face. Some have channels running down from them.

Some have channels running down from them. Natural fissures, etc. may have been incorporated into the design.

Natural fissures, etc. may have been incorporated into the design. Extensive quarrying took place at Ballochmyle and many glyphs may have been destroyed.

Extensive quarrying took place at Ballochmyle and many glyphs may have been destroyed.

The basic 'cup' is the most common carving however a wide range of glyphs exist with single to multiple concentric circles that are sometimes cut through in various ways by channels, etc. Where concentric rings exist the central cup often appears to dominate in depth and size[13] suggesting that they were subject to repeated reworking over a period of time. Some incomplete or poorly formed glyphs exist here suggesting that different persons were involved in making them and frequent overlays of existing glyphs with either 'cups' or 'cup rings' suggests that they were created over an extended period of time.[14]

Studies suggest that distinct stylistic groupings may be present with one panel area having simple cups and cups with grooves, whilst another area has predominately bold cups with multiple concentric rings.[15] An area with an apparent Lombardic style lettering may read 'ASAID' with two or three unreadable leading letters and a likely lost section. The final element is a date '1751' that is considered authentic but did not lead to further recorded investigation.[16]

Evidence suggests that cup and ring art was created from the Neolithic through to the Bronze Age, that is approximately 4000 BC to 1500 BC.[17]

Creation and meaning

Cup and ring mark stones are frequently found throughout Britain, with over 2500 sites in England alone,[18] however an unusual feature of those at Ballochmyle is that they have been carved on nearly or actual vertical surfaces rather than horizontal and often 'altar-like' exposed stone outcrops.[19][20] These types of carvings were created using 'hammerstones' or 'peckers', examples of these have been found elsewhere, hitting the surface of the rock repeatedly or using a grinding motion until the desired design was formed[21] Some of the long grooves appear to be a series of cups that were then joined together. The soft nature of the stone at Ballochmyle gives insights into how the glyphs were created with many small holes that could not have been formed by a hammering action.

The contrast with the original rock surface and the effect of shadow and rain usually makes the markings stand out however hints of the use of coloured pigments have been found at other sites[22] and such things as animal fat, charcoal, plants dyes, etc. could have been used during various types of ceremonies to enhance the glyphs or as part of their cultural use.[23]

The frequency and widespread use of the same glyphs or motifs indicates that they had definite interpretive meanings and significance to the cultures that created them and these developed and then persisted over thousands of years.[24] The locations indicate that these carvings were mostly for public display and not usually intended as part of secret practices where the fact that they were hidden was important.[25]

It may be relevant that the Ballochmyle area has both spectacular geological formations and geographical features in addition to the presence of a significant liminal zone in the form of a major watercourse, the River Ayr. Carvings into rocks can have deeper meanings such as with the carved footprint Petrosomatoglyphs at Dunadd in Argyll, linking a person literally to the land. The concept of the Anima locus is pertinent here, that is the 'soul' of a place, its essential personality as perceived in the imagination and emotions of visitors. A concept linked to the belief in supernatural spirits of nature as residing in stones, springs, mountains, islands, trees, etc.[26] A form of religious significance linked to life and death, past and present, real and spiritual worlds, etc. has been proposed.[27]

A significant factor is that, as previously stated, they were created from Neolithic through to the Bronze Age, that is approximately 4000 BC to 1500 BC[28] and they ceased when the Celtic Culture began to dominate and suppress older cultural practices. During this time smaller nomadic groups that might visit certain sites seasonally developed into sedentary communities with hierarchical leadership structures and specific communal religious practices.[29]

Many 'galleries' of cup and ring mark art are in prominent places within the landscape, such as river gorges, waterfalls, outcrops, caves, etc. and it has been suggested that they may have defined territorial boundaries, either for a locality or for a significant land holding.[30] Few prehistoric track ways have been positively identified however some link with the more practical aspects of Ley lines may be indicated by the observation that cup and ring art is sometimes found overlooking natural harbours, on prominent natural landscape features, in mountain passes, along valley sides, at the entrances to inland routes, etc.[31]

It is thought that natural features of the rock faces may influence the cup and ring mark sizes, distribution and type in addition to 'framing' the carvings. Fissures, grooves, wind erosion marks, cracks, dune bedding, etc. may all have been regarded by the Cup and ring mark carvers as significant and meaningful in their own right to be copied, enhanced, removed or incorporated as possibly the work of their 'ancestors' or even the works of the gods themselves.[32]

Some cup and ring mark panels may have only been used seasonally and the varying level of complexity at sites has been interpreted as being both more and less significant in terms of the level of meaning present.[33]

The universality of cup and ring markings suggest a commonality of the origins of such glyphs that may relate to natural phenomena that are deemed significant, such as the concentricles that form on water when an object or offering is placed in it and although this may have been interpreted differently by the many cultures involved, the liminality with associated themes of thresholds and communication with the 'other side' may be one explanation for the use of cup and rings rather than the extensive use of glyphs such as ovals, boxes, triangles, star-shapes, etc.

Surveys of the markings

In 2015 AOC Archaeology group were employed by the Forestry Commission Scotland to carry out a survey of laser scanning and photogrammetry on the Ballochmyle cup and ring marks. Laser scanning recorded the glyphs in 3D in minute detail, taking millions of measurements. The Photogrammetry involved photographing the site from many different angles and then bringing the data together to create a 3D model.[34] The RCAHMS carried out a survey on behalf of Historic Scotland in 1987 and a series of drawings were lodged with what is now Historic Environment Scotland.[35]

See also

- Dalgarven Mill – Museum of Ayrshire Country Life and Costume - The site of an unusual cup and ring mark stone.

References

- Notes

- ↑ Love (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. p. 152.

- ↑ Stevenson (2010). Cup-and-Ring Markings at Ballochmyle, Ayrshire. p. 33.

- ↑ (Historic Environment Scotland & SM4484)

- ↑ "Detailed Survey of Ballochmyle Cup and Ring Marks, Ayrshire". AOC Archaeology Group. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ↑ Stevenson (2010). Cup-and-Ring Markings at Ballochmyle, Ayrshire. p. 33.

- ↑ Stevenson (2010). Cup-and-Ring Markings at Ballochmyle, Ayrshire. p. 33.

- ↑ Stevenson (2010). Cup-and-Ring Markings at Ballochmyle, Ayrshire. p. 38.

- ↑ "Detailed Survey of Ballochmyle Cup and Ring Marks, Ayrshire". AOC Archaeology Group. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ↑ "Cup and Ring Marked Rock (Prehistoric)". RCAHMS. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ↑ Campbell (2003). Ayrshire. A Historical Guide. p. 138.

- ↑ Stevenson (2010). Cup-and-Ring Markings at Ballochmyle, Ayrshire. p. 33.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 2.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 3.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 3.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 35 & 36.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 36.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 5.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 1.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 33.

- ↑ "Cup and Ring Marked Rock (Prehistoric)". RCAHMS. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 3.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 5.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 5.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 7.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 9.

- ↑ Pennick (1996). Celtic Sacred Landscapes. pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 8.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 5.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 7.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 8.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 8.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 8.

- ↑ Sharpe (2008). England's Rock Art. p. 9.

- ↑ "Detailed Survey of Ballochmyle Cup and Ring Marks, Ayrshire". AOC Archaeology Group. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ↑ "Cup and Ring Marked Rock (Prehistoric)". RCAHMS. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- References

- Campbell, Thorbjørn (2003). Ayrshire. A Historical Guide. Edinburgh : Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-267-0

- Historic Environment Scotland. "Ballochmyle Viaduct,rock carvings 280m NE of (SM4484)". Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- Love, Dane (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. Ayr : Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- Pennick, Nigel (1996). Celtic Sacred Landscapes. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-01666-6. P. 13 - 15.

- Sharpe, Kate, Barnett, Tertia et al. (2008). England's Rock Art. The Prehistoric Rock Art of England. English Heritage & Northumberland County Council. ISBN 1-873402-28-7.

- Stevenson, J.B. (2010). Cup-and-Ring Markings at Ballochmyle, Ayrshire. Glasgow Archaeological Journal. V.18, Issue 18, ISSN 0305-8980.

External links

- Video footage of the Ballochmyle cup and ring marks

- Medieval and Later Carvings at Ballochmyle

- Exploring the designs and meanings of the rock carvings at Ballochmyle

- Creative archaeological visualization of the rock art at Ballochmyle

- The Modern Antiquarian - photographic record