A ball balancing robot also known as a ballbot is a dynamically-stable mobile robot designed to balance on a single spherical wheel (i.e., a ball). Through its single contact point with the ground, a ballbot is omnidirectional and thus exceptionally agile, maneuverable and organic in motion compared to other ground vehicles. Its dynamic stability enables improved navigability in narrow, crowded and dynamic environments. The ballbot works on the same principle as that of an inverted pendulum.

History

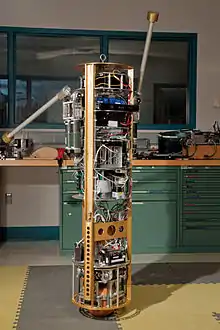

The first successful ballbot was developed in 2005[6][7][8] by Prof. Ralph Hollis of the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), Pittsburgh, USA and it was patented in 2010.[9] The CMU Ballbot[8][10][11][12] is built to be of human size, both in height and footprint. Prof. Hollis and his group at CMU demonstrated that the ballbot can be robust to disturbances including kicks and shoves, and can also handle collisions with furniture and walls.[13][14][15] They showed that a variety of interesting human-robot physical interaction behaviors can be developed with the ballbot,[16][17] and presented planning and control algorithms to achieve fast, dynamic and graceful motions using the ballbot.[18][19][20] They also demonstrated the ballbot's capability to autonomously navigate human environments to achieve point-point and surveillance tasks.[21][22][23] A pair of two degrees of freedom (DOF) arms was added to the CMU Ballbot[8] in 2011, making it the first and currently, the only ballbot in the world with arms.[24][25][26]

In 2005, around the same time when CMU Ballbot[8] was introduced, a group of researchers at University of Tokyo independently presented the design for a human-ridable ballbot wheelchair that balances on a basketball named "B. B. Rider".[27] However, they reported only the design and never presented any experimental results.[27] Around the same time, László Havasi from Hungary independently introduced another ballbot called ERROSphere.[28] The robot did not reliably balance and no further work was presented.

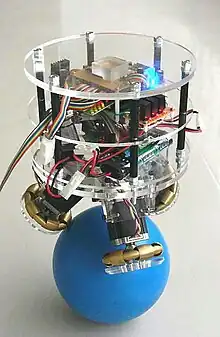

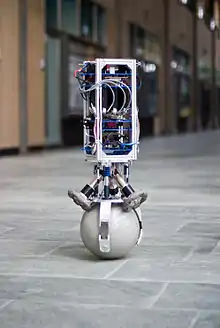

Since the introduction of CMU Ballbot[8] in 2005, several other groups around the world have developed ballbots. Prof. Masaaki Kumagai developed BallIP in 2008[29] at Tohoku Gakuin University, Japan. Prof. Kumagai and his group demonstrated the capability of ballbots to carry loads and be used for cooperative transportation.[30] They developed a number of small ballbots and demonstrated cooperative transportation using them.[30][31] A group of mechanical engineering students at ETH Zurich, Switzerland developed Rezero in 2010.[32] Rezero re-emphasized the fast and graceful motions that can be achieved using ballbots.[33]

Tomás Arribas (Spain) developed the first ballbot using LEGO Mindstorms NXT in 2008 as the Master Project at University of Alcala.[34][35] He developed a simulation project with Microsoft Excel to easily simulate the system.[36] As part of the research carried out inside the Space Research Group of the University of Alcalá (SRG-UAH), Spain, the work team, specialised in optimal control and planning applied to non-linear dynamic systems, published in 2012 the article called "A Monoball Robot Based on LEGO Mindstorms"[37] This article describes the math model and trajectory control as a baseline to unstable and non-linear control systems.

Yorihisa Yamamoto (Japan) inspired by Tomás Arribas's project, developed a ballbot using LEGO Mindstorms NXT in 2009.[38][39] He created a detailed demo to build, model and create controllers using MATLAB.[38] A group of mechanical engineering students at University of Adelaide (Australia) developed both a LEGO ballbot and a full-scale ballbot in 2009.[40] A group of students from ITMO University (Russia) introduced an algorithm and constructed a ballbot based on LegoNXT robotics kit which performed stability with only two actuators used.[41] Videos on YouTube present ballbots developed around the world. Some of them have been developed using LEGO Mindstorms NXT.[42][43][44][45][46] Other custom designs use omni-wheels to actuate the ball.[47][48][49][50]

Thomas Kølbæk Jespersen (Denmark) developed the Kugle ballbot as his final master thesis in 2019.[51] The Kugle ballbot is a human-sized ballbot developed as part of an ongoing Human Robot Interaction research project at Aalborg University. Equipped with three motors and omniwheels, an onboard Intel NUC, two SICK LiDARs, an ARM microprocessor and a tablet on the top, the robot is capable of maneuvering autonomously in indoor environments and guide people around. The master thesis takes a different approach to the system modelling by deriving a non-linear quaternion-based dynamic model which is used to derive a non-linear sliding mode controller to stabilize the balance and a path-following model predictive controller to plan and execute smooth trajectories. The complete master thesis and all material including MATLAB source code and C++ controller implementations are publicly available on GitHub.[52]

Ballbots have also appeared in the science fiction world. Pixar's 2008 movie Wall-E featured "M-O" (Microbe Obliterator), a ballbot cleaning robot. Syfy's 2010 TV series Caprica featured "Serge", a ballbot butler robot.[53]

Motivation and characteristics

Historically, mobile robots have been designed to be statically stable, which results in the robot not needing to expend energy while standing still. This is typically achieved through the use of three or more wheels on a base. In order to avoid tipping, these statically-stable mobile robots have a wide base for a large polygon of support, and a lot of dead weight in the base to lower the center of gravity. They also tend to have low acceleration or deceleration to avoid tipping. The wide base makes it difficult for statically-stable mobile robots to navigate cluttered human environments. Moreover, these robots have several other limitations that make them poorly suited to a constantly changing human environment. They can neither roll in any direction, nor can they turn in place.[8]

The desire to build tall and narrow mobile robots that do not tip over led to development of balancing mobile robots like the ballbot. A ballbot generally has a body that balances on top of a single spherical wheel (ball). It forms an underactuated system, i.e., there are more degrees of freedom (DOF) than there are independent control inputs. The ball is directly controlled using actuators, whereas the body has no direct control. The body is kept upright about its unstable equilibrium point by controlling the ball, much like the control of an inverted pendulum.[8] This leads to limited but perpetual position displacements of the ballbot. The counter-intuitive aspect of the ballbot motion is that in order to move forward, the body has to lean forward and in order to lean forward, the ball must roll backwards. All these characteristics make planning to achieve desired motions for the ballbot a challenging task. In order to achieve a forward straight line motion, the ballbot has to lean forward to accelerate and lean backward to decelerate.[14][18][24][32] Further, the ballbot has to lean into curves in order to compensate for centripetal forces, which results in elegant and graceful motions.[18][22][24][32]

Unlike two-wheeled balancing mobile robots like Segway that balance in one direction but cannot move in the lateral direction, the ballbot is omni-directional and hence, can roll in any direction. It has no minimal turning radius and does not have to yaw in order to change direction.

System description

Major design parameters

The most fundamental design parameters of a ballbot are its height, mass, its center of gravity and the maximum torque its actuators can provide. The choice of those parameters determine the robot's moment of inertia, the maximum pitch angle and thus its dynamic and acceleration performance and agility. The maximum velocity is a function of actuator power and its characteristics. Besides the maximum torque, the pitch angle is additionally upper bounded by the maximum force which can be transmitted from the actuators to the ground. Therefore, friction coefficients of all parts involved in force transmission also play a major role in system design. Also, close attention has to be paid to the ratio of the moment of inertia of the robot body and its ball in order to prevent undesired ball spin, especially while yawing.[32]

Ball and actuation

The ball is the core element of a ballbot, it has to transmit and bear all arising forces and withstand mechanical wear caused by rough contact surfaces. A high friction coefficient of its surface and a low inertia are essential. The CMU Ballbot,[8] Rezero[32] and Kugle[51] used a hollow metal sphere with poly-urethane coating. B.B. Rider[27] used a basketball, while BallIP[29] and Adelaide Ballbot[40] used bowling balls coated with a thin layer of rubber.

In order to solve the rather complex problem of actuating a sphere, a variety of different actuation mechanisms have been introduced. The CMU Ballbot[8] used an inverse mouse-ball drive mechanism. Unlike the traditional mouse ball that drives the mouse rollers to provide computer input, the inverse mouse-ball drive uses rollers to drive the ball producing motion. The inverse mouse-ball drive uses four rollers to drive the ball and each roller is actuated by an independent electric motor. In order to achieve yaw motion, the CMU Ballbot uses a bearing, slip-ring assembly and a separate motor to spin the body on top of the ball.[14] The LEGO Ballbot[38] also used an inverse mouse-ball drive, but used normal wheels to drive the ball instead of rollers.

Unlike CMU Ballbot[14] both BallIP,[29] Rezero[32] and Kugle[51] use omni-wheels to drive the ball. This drive mechanism does not require a separate yaw drive mechanism and allows direct control of the yaw rotation of the ball. Unlike CMU Ballbot[14] that uses four motors for driving the ball and one motor for yaw rotation, BallIP,[29] Rezero[32] and Kugle[51] use only three motors for both the operations. Moreover, they only have three force transmission points compared to four points on CMU Ballbot. Since the contact between an omni-wheel and the ball should be reduced to a single point, most available omni-wheels are not properly suitable for this task because of the gaps between the individual smaller wheels that result in an unsteady rolling motion. Therefore, the BallIP[29] project introduced a more complex omni-wheel with a continuous circumferential contact line. The Rezero[32] team equipped this omni-wheel design with roller bearings and a high-friction coating.[32] They also additionally fitted a mechanical ball arrester that presses the ball against the actuators in order to further increase friction forces and a suspension to dampen vibrations.[32] The Kugle robot is equipped with a skirt which holds the ball in place to avoid that the ball gets pushed out during large inclinations. The Adelaide Ballbot[40] uses wheels for its LEGO version and traditional omni-wheels for its full-scale version.

Prof. Masaaki Kumagai,[3] who developed BallIP[29] introduced another ball drive mechanism that uses partially sliding rollers.[54] [55] The objective of this design was to develop 3-DOF actuation on the ball using a low cost mechanism.

Sensors

In order to actively control the position and body orientation of a ballbot by a sensor-computer-actuator framework, beside a suitable microprocessor or some sort of other computing unit to run the necessary control loops, a ballbot fundamentally requires a series of sensors which allow to measure the orientation of the ball and the ballbot body as a function of time. To keep track of the motions of the ball, rotary encoders (CMU Ballbot,[8] BallIP,[29] Rezero,[32] Kugle[51]) are usually used. Measuring the body orientation is more complicated and is often done by the use of gyroscopes (NXT Ballbots[38][40]) or, more generally, an Inertial Measurement Unit (CMU Ballbot,[8] BallIP,[29] Rezero,[32] Kugle[51]) which includes an accelerometer, gyroscope and possibly magnetometer whose measurements are fused into the body orientation through AHRS algorithms.

The CMU Ballbot[8] uses a Hokuyo URG-04LX Laser Range Finder to localize itself in a 2D map of the environment.[22][23] It also uses the laser range finder for detecting obstacles and avoiding them.[22][23] Conversely the Kugle robot[51] uses two SICK TiM571 2D LiDAR to localize itself, perform obstacle avoidance and detect people for guidance.

Arms

The CMU Ballbot[8] is the first and currently, the only ballbot to have arms.[24][25][26] It has a pair of 2-DOF arms that are driven by series-elastic actuators. The arms are hollow aluminium tubes with a provision to add dummy weights at their ends. In their present state, the arms cannot be used for any significant manipulation, but are used to study their effects on the dynamics of ballbot.[24][25][26]

System modeling, planning and control

The mathematical MIMO-model which is needed in order to simulate a ballbot and to design a sufficient controller which stabilizes the system, is very similar to an inverted pendulum on a cart. The LEGO NXT Ballbot,[38] Adelaide Ballbot,[40] Rezero[32] and Kugle[51] include actuator models in their robot models, whereas CMU Ballbot[8] neglects the actuator models and models the Ballbot as a body on top of a ball. Initially, CMU Ballbot[8] used two 2D planar models in perpendicular planes to model the ballbot[13][14] and at present, uses 3D models without yaw motion for both the ballbot without arms[18][21][22] and the ballbot with arms.[24] BallIP[29] uses a model that describes the dependence of the ball position on the wheel velocities and the body motion. Rezero[32] uses a full 3D model that includes yaw motion too. Kugle[51] uses a fully coupled quaternion-based 3D model which couples the motion of all axes.

The ballbots (CMU Ballbot,[8] BallIP,[29] NXT Ballbot,[38] Adelaide Ballbot,[40] Rezero[32]) use linear feedback control approaches to maintain balance and achieve motion. The CMU Ballbot[8] uses an inner balancing control loop that maintains the body at desired body angles and an outer loop controller that achieves desired ball motions by commanding body angles to the balancing controller.[13][14][18][21][22][24] The Kugle robot is tested with both linear feedback controllers (LQR) and non-linear sliding mode controllers to show the benefit of its coupled dynamic quaternion model.[51]

A ballbot is a shape-accelerated underactuated system. The inclination angles of a ballbot is thus dynamically linked to the resulting accelerations of the ball and robot leading to an underactuated system. The CMU Ballbot plans motions in the space of body lean angles in order to achieve fast, dynamic and graceful ball motions.[18][21][22][24] With the introduction of arms, CMU Ballbot uses its planning procedure to plan in the space of both body lean angles and arm angles to achieve desired ball motions.[22][24][25] Moreover, it can also account for cases where the arms are constrained to certain specific motions and only body angles have to be used to achieve desired ball motions.[26] The CMU Ballbot uses an integrated planning and control framework to autonomously navigate human environments.[22][23] Its motion planner plans in the space of controllers to produce graceful navigation, and achieves point-point and surveillance tasks. It uses the laser range finder to actively detect and avoid both static and dynamic obstacles in its environment.[22][23]

For Kugle a path-planning model predictive controller (MPC) is designed to control the inclination angles of the ballbot to follow a given path. A path-following strategy is chosen over common trajectory or reference tracking controllers to accommodate for the temporally lacking behaviour of ballbots due to the underactuated nature. The path is parameterized as a polynomial and included into the cost-function of the MPC. A set of soft-constraints ensures that obstacles are avoided and that progress is made with a desired speed.[51]

Safety features

The biggest concern with a ballbot is its safety in case of a system failure. There have been several attempts in addressing this concern. The CMU Ballbot[8] introduced three retractable landing legs that allow the robot to remain standing (statically-stable) after being powered down. It is also capable of automatically transitioning from this statically-stable state to the dynamically-stable, balancing state and vice versa.[13][15] Rezero featured a roll-over safety mechanism in order to prevent serious damage in case of a system failure.[32]

Possible applications

Due to its dynamic stability, a ballbot can be tall and narrow, and can also be physically interactive, making it an ideal candidate for a personal mobile robot.[8] It can act as an effective service robot at homes and offices and offer guidance to people in e.g. malls and airports.[51] The present day ballbots[8][29][32] are restricted to smooth surfaces. The concept of the ballbot has attracted a lot of media attention,[10][11][12][31][33] and several ballbot characters have appeared in Hollywood movies.[56][53] Hence, the ballbot has a variety of applications in the entertainment industry, including toys.

Notable Ballbot projects

- Academic projects:

- The Ballbot Research Platform at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) (2005)[1]

- BallIP at Tohoku Gakuin University (2007)[3]

- Rezero at ETH Zurich (2010)[4]

- Kugle at Aalborg University (AAU) (2018)[5]

- Ballbot-based wheelchair prototype at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (2023)[57]

- Industrial projects:

References

- 1 2 3 CMU Ballbot

- ↑ Prof. Ralph Hollis

- 1 2 3 Prof. Masaaki Kumagai

- 1 2 Markus Waibel (June 2010). "Project Rezero: Ball Balancing Robot With Style". spectrum.ieee.org.

- 1 2 Kugle - Modelling and Control of a Ball-balancing

- ↑ Tom Lauwers; George Kantor; Ralph Hollis (October 2005). "One is Enough!" (PDF). 12th International Symposium on Robotics Research.

- ↑ Tom Lauwers; George Kantor; Ralph Hollis (May 2006). "A Dynamically Stable Single-Wheeled Mobile Robot with Inverse Mouse-Ball Drive" (PDF). IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. pp. 2884–2889.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Ralph Hollis (October 2006). "Ballbots". Scientific American. pp. 72–78.

- ↑ Ralph Hollis (Dec 7, 2010). "Dynamic balancing mobile robot". US Patent #7847504.

- 1 2 "CMU Ballbot on Discovery Channel's Daily Planet". YouTube (VIDEO). June 2007.

- 1 2 "CMU Ballbot on ROBORAMA". YouTube (VIDEO). August 2006. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- 1 2 "CMU Ballbot on UK's Gadget Show". YouTube (VIDEO). January 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Umashankar Nagarajan; Anish Mampetta; George Kantor; Ralph Hollis (May 2009). "State Transition, Balancing, Station Keeping and Yaw Control for a Dynamically Stable Single Spherical Wheel Mobile Robot" (PDF). IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. Kobe, Japan. pp. 998–1003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Umashankar Nagarajan; George Kantor; Ralph Hollis (May 2009). "Trajectory Planning and Control of a Dynamically Stable Single Spherical Wheel Mobile Robot" (PDF). IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. Kobe, Japan. pp. 3743–3748.

- 1 2 "CMU Ballbot: Overview". YouTube (VIDEO). December 2008. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- ↑ Umashankar Nagarajan; George Kantor; Ralph Hollis (March 2009). "Human-Robot Physical Interaction with Dynamically Stable Mobile Robots" (PDF). IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. San Diego, USA. pp. 3743–3748.

- ↑ "CMU Ballbot: Human-Robot Physical Interaction". YouTube (VIDEO). December 2008. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Umashankar Nagarajan (June 2010). "Dynamic Constraint-based Optimal Shape Trajectory Planner for Shape-Accelerated Underactuated Balancing Systems" (PDF). Robotics: Science and Systems. Zaragoza, Spain.

- ↑ "CMU Ballbot: Fast Motions". YouTube (VIDEO). June 2010. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- ↑ "CMU Ballbot: Fast, Graceful Maneuvers". YouTube (VIDEO). December 2010. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- 1 2 3 4 Umashankar Nagarajan; George Kantor; Ralph Hollis (December 2010). "Hybrid Control for Navigation of Shape-Accelerated Underactuated Balancing Systems" (PDF). IEEE Conference on Decision and Control. Atlanta, USA. pp. 3566–3571.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Umashankar Nagarajan; George Kantor; Ralph Hollis (May 2012). "Integrated Planning and Control for Graceful Navigation of Shape-Accelerated Underactuated Balancing Mobile Robots" (PDF). IEEE Conference on Decision and Control. St. Paul, USA.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Umashankar Nagarajan; Byungjun Kim; Ralph Hollis (May 2012). "Planning in High-dimensional Shape Space for a Single-wheeled Balancing Mobile Robot with Arms" (PDF). IEEE Conference on Decision and Control. St. Paul, USA.

- 1 2 3 4 "CMU Ballbot: Motion with Arms". YouTube (VIDEO). April 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- 1 2 3 4 "CMU Ballbot: Motions with Constraints on Arms". YouTube (VIDEO). October 2011. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- 1 2 3 Tatsuro Endo; Yoshihiko Nakamura (July 2005). "An Omnidirectional Vehicle on a Basketball". 12th International Conference on Advanced Robotics (PDF): 573–578.

- ↑ László Havasi (June 2005). "ERROSphere: an Equilibrator Robot". International Conference on Control and Automation (PDF). Budapest, Hungary: 971–976.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 M Kumagai; T Ochiai (October 2008). "Development of a Robot Balancing on a Ball". International Conference on Control. Seoul, Korea: Automation and Systems: 433–438.

- 1 2 M Kumagai; T Ochiai (May 2009). "Development of a Robot Balanced on a Ball: Application of passive motion to transport". International Conference on Robotics and Automation. Kobe, Japan: 4106–4111.

- 1 2 "BallIP on IEEE Spectrum". April 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Simon Doessegger; Peter Fankhauser; Corsin Gwerder; Jonathan Huessy; Jerome Kaeser; Thomas Kammermann; Lukas Limacher; Michael Neunert (June 2010). "Rezero, Focus Project Report" (PDF). Autonomous Systems Lab, ETH Zurich Institute of Technology (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Rezero on TED Talks" (VIDEO). July 2011.

- ↑ Tomás Arribas (August 2008). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FZ5K0tZ2ZOk

- ↑ Tomás Arribas (30 December 2010). "NXT BallBot: Balancing Robot Omnidirectional Trajectory correction". Archived from the original on 2021-12-19 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Arribas, Tomás (5 January 2011). "NXTBallbot balancing robot Simulation with Microsoft Excel: NXT Ballbot Simulation with Microsoft Excel".

- ↑ ( S. Sánchez, T. Arribas, M. Gómez and O. Polo, “A Monoball Robot Based on LEGO Mindstorms,” IEEE Control Systems Magazine, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 71–83, 2012.)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yorihisa Yamamoto (April 2009). "NXT Ballbot Model-Based Design.pdf" (PDF). p. 47.

- ↑ "LEGO NXT Ballbot". YouTube (VIDEO). January 2009. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Ballbot at University of Adelaide". YouTube (VIDEO). October 2009. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- ↑ S, Borgul Alexander; S, Gromov Vladislav; A, Zimenko Konstantin; Maklashevich, Sergey (28 September 2011). "Ballbot stabilization algorithm". Journal Scientific and Technical of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics. 75 (5): 58.

- ↑ Samuel Jackson (13 August 2011). "Ballbot - A dynamically stable inverted pendulum balancing on a bowling ball". Archived from the original on 2021-12-19 – via YouTube.

- ↑ double051 (14 March 2011). "2-Dimension Inverted Pendulum". Archived from the original on 2021-12-19 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "YouTube". YouTube.

- ↑ "YouTube". YouTube.

- ↑ "YouTube". YouTube.

- ↑ antonio88m (11 February 2011). "Ballbot - prima versione". Archived from the original on 2021-12-19 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ StAstRobotics (1 March 2011). "AST Ballbot - G1". Archived from the original on 2021-12-19 – via YouTube.

- ↑ aoki2001 (14 November 2010). "玉乗りロボット1号". Archived from the original on 2021-12-19 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Jeroen Waning (2 December 2011). "Self-balancing Arduino Ballbot - SPSU senior design project". Archived from the original on 2021-12-19 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Jespersen, Thomas Kølbæk (April 2019). Kugle - Modelling and Control of a Ball-balancing (PDF). Master Thesis, AAU.

- ↑ Jespersen, Thomas Kølbæk. "Kugle ballbot repository". GitHub.

- 1 2 "Serge - Battlestar Wiki". Archived from the original on 2010-04-02. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ Masaaki Kumagai (October 2010). "Development of a ball drive unit using partially sliding rollers — an alternative mechanism for semi-omnidirectional motion —". 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. Taipei,Taiwan. pp. 3353–3357. doi:10.1109/IROS.2010.5651007. ISBN 978-1-4244-6674-0. S2CID 15901355.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Ball Actuation using Partial Sliding Rollers". YouTube. October 2010. Archived from the original on 2021-12-19.

- ↑ WALL-E

- ↑ Hands-free wheelchair prototype achieves major milestone

- ↑ Bossa Nova Robotics Launches Mobi Research Ballbot

- ↑ BionicMobileAssistant: Mobile Robot System with Pneumatic Gripper Hand