| Bau | |

|---|---|

Tutelary goddess of Girsu | |

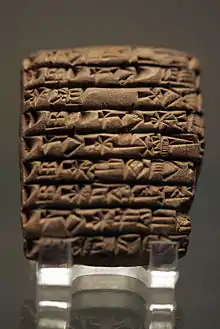

Bust of a goddess, perhaps Bau, from Girsu. Louvre Museum. | |

| Major cult center | Girsu, Lagash, later Kish |

| Symbol | waterfowl, scorpion |

| Personal information | |

| Parents |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | Igalim, Shulshaga, Ḫegir, six other deities |

Bau, also read Baba (cuneiform: 𒀭𒁀𒌑 dBa-U2), was a Mesopotamian goddess. The reading of her name is a subject of debate among researchers, though Bau is considered the conventional spelling today.[1] While initially regarded simply as a life-giving deity, in some cases associated with the creation in mankind, over the course of the third and second millennia BCE she also acquired the role of a healing goddess. She could be described as a divine midwife. In art she could be depicted in the company of waterfowl or scorpions.

In sources from Lagash and Girsu, Bau's husband was the god Ningirsu. Among their children were deities such as Igalim, Shulshaga and Ḫegir. While they could still be regarded as a couple in later sources, from the Old Babylonian period onwards Bau was also viewed as the wife of Zababa, the tutelary god of Kish. Another deity associated with her was her attendant goddess Lammašaga. Most likely for political reasons, Bau also came to be associated, and partially syncretised, with the medicine goddess Ninisina. However, their character was not identical, for example Bau was not associated with dogs and was not invoked against demons in incantations. In the late second millennium BCE she also came to be associated with Gula, and could be equated with her, though texts where they are two separate goddesses are known too. In one case, Bau is described as the deity who bestowed Gula's position upon her.

The earliest evidence indicates that Bau's initial cult center was Girsu, and that early on she also came to be worshipped in Lagash. Multiple kings of this city left behind inscriptions which mention her, and some of them, for example Uru'inimgina, referred to her as their divine mother. She is also attested in the theophoric names of many ordinary people. While the area where she was initially worshipped declined in the Old Babylonian period, she was transferred to Kish, and continued to be venerated there as late as in the Neo-Babylonian period. She is also attested in texts from Uruk dating to the Seleucid period.

Name

The meaning of Bau's name is unknown.[2][3] Thorkild Jacobsen's proposal that it was "an imitation of dog's bark, as English 'bowwow'" is regarded as erroneous today, as unlike other healing goddesses (Gula, Ninisina, Nintinugga and Ninkarrak) Bau was not associated with dogs.[4][1]

The reading of Bau's name has historically been a subject of debate in Assyriology, and various possibilities have been proposed, including Bau, Baba, Bawu and Babu.[5] While "Baba" is a relatively common reading older in literature, the evidence both in favor and against it is inconclusive.[6] Edmond Sollberger considered "Bawa" to be the original form, with Baba being a latter pronunciation, similar to the change from Huwawa to Humbaba.[7] Maurice Lambert assumed Baba was the Akkadian reading and that as such in scholarship it should be only employed in strictly Akkadian contexts.[7] Richard L. Litke regarded "Bau" as the most likely pronunciation.[4] Giovani Marchesi notes that it is not certain if the phonetic spelling "Baba" found in a few Old Akkadian texts corresponds to this goddess or another deity, though he remarks it does seem that "Baba" and "Bau" were interchangeable in the writing of theophoric names, for example in the case of the legendary queen Kubaba/Ku-Bau.[8] He concludes that Bau was most likely the original pronunciation at the time when the orthography of the name was standardized in the third millennium BCE.[9] However, Gonazalo Rubio disagrees with Marchesi's conclusions and argues that the reading Baba would fit the pattern evident in other names of Mesopotamian deities with no clear Sumerian or Semitic etymologies, such as Alala, Bunene or Zababa.[10] Christopher Metcalf in a more recent publication notes that the reading Bau is supported by the attestations of the dative form dBa-U2-ur2.[11] Due to the uncertainties surrounding the reading of the name, some experts favor the spelling BaU, or Ba-U2, including Manuel Ceccarelli,[12] Jeremiah Peterson,[13] Julia M. Asher-Greve and Joan Goodnick Westenholz.[14] However, Irene Sibbing-Plantholt notes that as of 2022, Bau can be considered the conventional spelling.[1]

Character and iconography

The earliest sources represent Bau as a "life-giving" and "motherly" deity.[15] A hymn from the reign of Ishme-Dagan preserves a tradition according to which she was believed to be the mother of mankind.[16] While not a healing goddess at first, Bau acquired traits of this class of deities at some point in the third millennium BCE.[17][18] Curiously, in sources from the third millennium BCE only Bau is referred to as an asû,[19] "physician."[20] At the same time, there is no evidence that physicians were involved in her cult, unlike in the cases of Gula, Ninisina and Nintinugga.[21] This might indicate her healing role was associated with domestic religious practices.[22]

As a healing goddess Bau was also connected to midwifery.[23] She could be described as (ama) arḫuš, "merciful (mother)."[24] It has been proposed that this epithet reflected "the knowledge of the female body," and that it designated deities bearing it as midwives.[25] A hymn praising Bau for her role as a midwife was composed to celebrate the birth of the child of queen Kubatum, wife of Shu-Sin.[3][15] She was also regarded as a goddess of abundance, and as such was depicted with a vase with flowing streams of water in art.[26] Furthermore, she was believed to be capable of mediating with other deities on behalf of supplicants.[27]

A depiction of Bau accompanied by a snake is known from a seal, and according to Julia M. Asher-Greve might indicate this animal was perceived as her symbol in the role of a healing deity.[28] This interpretation has been questioned by Irene Sibbing-Plantholt, who points out that while the owner of the seal, a certain Ninkalla, was a midwife, there is no other evidence for the association between Bau and snakes, and the animal therefore might fulfill a general apotropaic role.[29]

In other contexts, presumably pertaining to her role as a wife or mother, Bau could be depicted with scorpions (associated with marriage), swans or miscellaneous waterfowl.[30] The various symbols assigned to her indicate that she was a multifaceted deity[31] with a fluid sphere of influence.[32] However, in the case of works of art later than the end of the third millennium BCE identifying individual depictions of Bau is difficult.[15]

Associations with other deities

Bau's father was An, as already attested in an inscription of Gudea.[33] She was described as his firstborn daughter sometimes.[34] Her mother was the goddess Abba or Ababa/Abau (this writing of the name poses the same problems for interpretation as that of her daughter), attested in the Lamentation over the Destruction of Ur and in the god list An = Anum.[35] Another deity sharing the same name, known from a different An = Anum passage and first millennium BCE lamentation texts, was instead male and a son of Bau.[35]

Bau's husband was Ningirsu.[36] One of the few known reliefs showing a god with his wife sitting in his lap is most likely a depiction of this couple from the reign of Gudea (another similar one is instead interpreted as a depiction of Nanna and Ningal from the reign of Ur-Namma).[37] Such images were meant to highlight that the divine couples, depicted as loving spouses, act in unison, and that the corresponding kings had a special relation to them.[38] References to Bau and Ningirsu as a couple are also known from later sources, for example they appear together in two curse formulas inscribed on kudurru (boundary stones).[39] In sources from Lagash, the siblings Igalim and Shulshaga were regarded as their sons.[40] Furthermore, an inscription of Gudea labels the goddess Ḫegir as their daughter.[41] One of the Gudea cylinders states she was a member of a group referred to as "the seven lukur priestesses of Ningirsu" or "the septuplets of Bau."[42]

In Kish, where Bau was introduced in the Old Babylonian period,[43] she was regarded as the spouse of Zababa,[44] a local war god.[45] Initially Zababa was the husband of Ishtar of Kish (regarded as separate from Ishtar of Uruk), but after the Old Babylonian period she was replaced in the role of his spouse by Bau, though she continued to be worshiped independently.[43] Couples such as Bau and Zababa, which consisted of a healing goddess and a warrior god, were common in Mesopotamian mythology, with the most commonly referenced example being Ninisina and her husband Pabilsag.[46] A single older reference to Bau and Zababa as a couple is known from the Lament for Sumer and Ur.[43] Bau and Zababa appear together in various religious texts, including the incantation series Šurpu, a hymn to Nanaya, and various compositions from the north of Babylonia.[45] The tradition presenting them as a couple is also known from Assyrian sources, for example from a treaty of Ashur-nirari V.[39]

An association between Bau and Nergal is attested in Old Babylonian sources from Ur and in one case from Larsa as well.[47]

Bau's divine vizier (sukkal) was the goddess Lammašaga, "good guardian angel (lamma)," lamma being a class of tutelary and intercessory minor goddesses in Mesopotamian religion.[48] She had a temple of her own in Lagash,[14] and hymns dedicated to her are known from the curriculum of scribal schools.[49] In the past, attempts were sometimes made to prove was a manifestation of Bau rather than a separate goddess, but this view is no longer considered plausible.[50] A hymn formerly believed to be a praise of Bau, while sometimes referred to as Bau A according to the ETCSL naming system, has been subsequently identified as a composition dedicated to Lammašaga instead.[51] Bau herself was possibly sometimes addressed as a lamma in Lagash.[52] In a handful of inscriptions, Bau's mother, left nameless in them, is also designated as such a deity.[53]

Bau and medicine goddesses

A degree of syncretism occurred between Bau and Ninisina,[54] and the former is simply given as the name of the latter in Girsu in the composition Ninisina and the Gods.[15] A hymn composed on behalf of Ishme-Dagan describes Bau with epithets which normally belonged to Ninisina.[17] It is possible that the development of a connection between these goddesses was politically motivated and was supposed to help the kings of Isin with posing as rightful successors of earlier influential dynasties.[55] According to Manuel Ceccarelli it developed in parallel with the connection between their respective husbands, Ningirsu and Pabilsag.[56] The character of Bau and Ninisina was however not identical, for example the former typically does not appear in incantations and was not invoked as an opponent of demons, unlike the latter.[39] Her lack of association with dogs, well attested for other healing goddesses, might be related to this difference.[22]

Another medicine goddess associated with Bau was Gula,[57] though they were not closely connected with each other until the late second millennium BCE.[58] They were likely regarded as analogous in the Middle Assyrian period, with examples including the interchangeable use of their names in colophons and direct equation in a local version of the Weidner god list, but they were not always viewed as identical.[59] Irene Sibbing-Plantholt suggests that the phrase Bau ša qēreb Aššur might have been used specifically to differentiate Bau as a name of Gula and Bau as an independent goddess.[60] In the Gula Hymn of Bulluṭsa-rabi, composed at some point between 1400 and 700 BCE,[61] Bau is listed as one of the names of the eponymous goddess.[62] This composition, despite equating various goddesses with Gula, nonetheless preserves information about the individual character of each of them.[63] The section dedicated to Bau highlights her role as a life-giving deity.[64] However, a late Babylonian incantation states that Gula was exalted by the command of Bau, which affirms they were viewed as separate.[65] They also function separately from each other in sources pertaining to a festival held in Uruk in the first millennium BCE.[66] Bau's association with Zababa was also exclusive to her.[60]

Worship

In the third millennium BCE

.JPG.webp)

While the oldest attestations of Bau come from scribal school texts from Shuruppak from the Early Dynastic period, her original cult center was Girsu.[1] She was worshiped in the shrine Egalgasu, "house filled with counsel," which was located in the Etarsirsir,[67] a temple dedicated to her in the Uru-ku,[68] the so-called "sacred quarter" of the city.[69] References to this house of worship are available from the reign of Ur-Nanshe.[2] Bau was also worshiped in the Eninnu,[70] which was primarily a temple of Ningirsu.[71] The name Etarsirsir also referred to Bau's temple in the city of Lagash,[72] though she was not yet worshiped there in the Early Dynastic period.[1] It has been suggested that this might indicate she was initially not a separate goddess, but a secondary name of Lagashite Gatumdug, but this explanation is not considered plausible.[33] Attested members of the staff of Bau's temples from the Early Dynastic period include various types of clergy (for example gudu and gala); temple administrators (sanga); writers (dub-sar); musicians (nar); housekeepers (agrig); various artisans; shepherds; fishermen; and more.[73] Various kings of Lagash dedicated votive offerings to Bau, with particularly many being known from the reign of Uru'inimgina.[1] Some of the Lagashite rulers, including him, as well as Eanatum and Lugalanda, designated her as their divine mother, though sometimes this role was fulfilled by Gatumdag instead, for example in the case of Enanatum I and Enmetena.[74] Bau's connection to kings extended to the cult of deceased rulers as well.[18] She appears frequently in theophoric names from Lagash.[75][32] Examples include Bau-alša ("Bau shows mercy"), Bau-amadari ("Bau is the eternal mother"), Bau-dingirmu ("Bau is my deity"), Bau-gimabaša ("Who is merciful like Bau?"), Bau-ikuš ("Bau takes care"), Bau-menmu ("Bau is my crown"), Bau-umu ("Bau is my light"), Gan-Bau ("servant of Bau;" Gebhard Selz translates the first element as feminine), Geme-Bau ("maid of Bau"), Lu-Bau ("man of Bau"), and more.[76]

Bau's importance grew further during the reign of the Second Dynasty of Lagash (c. 2230-2110 BCE) on the account of her connection with Ningirsu.[77] Gudea elevated her rank to equal of that of Ningirsu, and called her "Queen who decides the destiny in Girsu."[26] This made her the highest ranking goddess of the local pantheon of Lagash,[27] putting her above Nanshe.[28] During the subsequent reign of the Third Dynasty of Ur, she was the second most notable goddess worshiped chiefly in association with her respective husband after Ninlil.[78] The highest cultic official of Bau in the province of Lagash, and as a result one of the most powerful political figures in it was an ereš-dingir priestess,[79] with one named Geme-Lamma being known from a number of seals.[80] While servants and scribes are depicted lead by minor goddesses to meet with Bau in seals, the high priestess was depicted interacting with the goddess directly.[79] In the same period Bau came to be worshiped in Nippur, though neither she not her husband Ningirsu were major members of the local pantheon.[1] According to Walther Sallaberger, she received offerings in the Ešumša, a temple of Ninurta.[81]

Later attestations

Kings from the dynasty of Isin, in particular Ishme-Dagan, showed interest in the cult of Bau, though she was not introduced to the pantheon of Isin itself, and in documents from it she only appears in theophoric names.[15] Evidence for the worship of Bau from the Old Babylonian period is scarce.[1] In Ur she is only attested near its end, always in association with Nergal.[47] While the original Lagashite cult of Bau declined alongside the city (a situation analogous to that of Ningirsu as an independent deity, as well as other southern deities such as Shara and Nanshe),[82] she continued to be worshiped in Kish in northern Babylonia.[43] Old Babylonian evidence for the presence of her worshipers in this city includes a record from the reign of Ammi-Ditana which mentions a woman serving as a courtyard purifier (kisalluḫḫatum) of this goddess, and a seal from Hammurabi's time whose owner referred to herself as a servant of Zababa and Bau.[81] She remained a major goddess of that city as late as the Neo-Babylonian period.[49] An inscription from the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II mentions the rebuilding of the local temple Edubba for both the city god, Zababa, and for Bau.[81] A cella dedicated to her bore the name Egalgasu, which originally referred to her shrine in Girsu.[67]

Elsewhere in the Middle Babylonian period and beyond, Bau retained a degree of popularity, and next to Ishtar and Gula was the most commonly invoked goddess in theophoric names.[39] One historically notable bearer of such a name was Bau-asītu, a daughter of Nebuchadnezzar II.[83] In Babylon, "Bau of Kish" was celebrated during certain festivals in the temple of Gula.[84] According to Andrew R. George, the temple Eulšarmešudu, "house of jubilation and perfect me," possibly located in Der and known from an unpublished hymn, might have been dedicated to Bau.[85] Her cult is also attested in Assyria, and she had a temple in which she was worshiped alongside Zababa in Assur.[83]

While Bau was not yet worshiped in Uruk in the Neo-Babylonian period,[86] she is mentioned in a text describing the procession of deities who took part in the akītu festival which was celebrated in this city in the Seleucid period.[87] She also occurs in a single theophoric name from this location.[88]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 139.

- 1 2 Selz 1995, p. 26.

- 1 2 Böck 2015, p. 330.

- 1 2 Marchesi 2002, p. 165.

- ↑ Marchesi 2002, p. 161.

- ↑ Marchesi 2002, pp. 161–163.

- 1 2 Marchesi 2002, p. 164.

- ↑ Marchesi 2002, p. 163.

- ↑ Marchesi 2002, p. 172.

- ↑ Rubio 2010, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Metcalf 2019, p. 24.

- ↑ Ceccarelli 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ Peterson 2009, p. 49.

- 1 2 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 54.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 140.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 142.

- 1 2 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 84.

- 1 2 Böck 2015, p. 329.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 45.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 1.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 157.

- 1 2 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 158.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 204.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 104.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 130.

- 1 2 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 189.

- 1 2 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 190.

- 1 2 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 205.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 141.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 266.

- 1 2 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 209.

- 1 2 Selz 1995, p. 102.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 63.

- 1 2 Samet 2014, p. 81.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 61.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 190-191.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 191.

- 1 2 3 4 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 143.

- ↑ Selz 1995, pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1992, p. 78.

- ↑ Selz 1995, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 78.

- ↑ Sallaberger 2016, p. 164.

- 1 2 Sallaberger 2016, p. 167.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 38.

- 1 2 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 53–54.

- 1 2 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 77.

- ↑ Metcalf 2019, p. 19.

- ↑ Metcalf 2019, p. 18.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Samet 2014, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Ceccarelli 2009, p. 32.

- ↑ Böck 2015, p. 331.

- ↑ Ceccarelli 2009, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 160.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 74-75.

- 1 2 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 75.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 100.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 12.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 116.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 101.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 97.

- ↑ Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 87.

- 1 2 George 1993, p. 89.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 148.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 157.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 202.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 134.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 149.

- ↑ Selz 1995, pp. 83–96.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 59.

- ↑ Selz 1995, p. 96.

- ↑ Selz 1995, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 19.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 66.

- 1 2 Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 203.

- ↑ Otto 2016, p. 124.

- 1 2 3 Sallaberger 2016, p. 166.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, pp. 21–22.

- 1 2 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 144.

- ↑ Asher-Greve & Westenholz 2013, p. 124.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 155.

- ↑ Krul 2018, p. 73.

- ↑ Krul 2018, p. 68.

- ↑ Krul 2018, p. 71.

Bibliography

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Westenholz, Joan G. (2013). Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources (PDF). ISBN 978-3-7278-1738-0.

- Böck, Barbara (2015). "Ancient Mesopotamian Religion: A Profile of the Healing Goddess". Religion Compass. Wiley. 9 (10): 327–334. doi:10.1111/rec3.12165. hdl:10261/125303. ISSN 1749-8171. S2CID 145349556.

- Ceccarelli, Manuel (2009). "Einige Bemerkungen zum Synkretismus BaU/Ninisina". In Negri Scafa, Paola; Viaggio, Salvatore (eds.). Dallo Stirone al Tigri, dal Tevere all'Eufrate: studi in onore di Claudio Saporetti (in German). Roma: Aracne. ISBN 978-88-548-2411-9. OCLC 365061350.

- George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103.

- Kobayashi, Toshiko (1992). "On Ninazu, as Seen in the Economic Texts of the Early Dynastic Lagaš". Orient. The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan. 28: 75–105. doi:10.5356/orient1960.28.75. ISSN 1884-1392. S2CID 191496612.

- Krul, Julia (2018). The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004364943_004. ISBN 9789004364936.

- Marchesi, Gianni (2002). "On the Divine Name dBA.Ú". Orientalia. GBPress- Gregorian Biblical Press. 71 (2): 161–172. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43076783. Retrieved 2021-08-04.

- Metcalf, Christopher (2019). Sumerian Literary Texts in the Schøyen Collection. Penn State University Press. doi:10.1515/9781646020119. ISBN 978-1-64602-011-9. S2CID 241160992.

- Otto, Adelheid (2016). "Professional Women and Women at Work in Mesopotamia and Syria (3rd and early 2nd millennia BC): The (rare) information from visual images". The Role of Women in Work and Society in the Ancient Near East. De Gruyter. pp. 112–148. doi:10.1515/9781614519089-009. ISBN 9781614519089.

- Peterson, Jeremiah (2009). God lists from Old Babylonian Nippur in the University Museum, Philadelphia. Münster: Ugarit Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86835-019-7. OCLC 460044951.

- Rubio, Gonzalo (2010). "Reading Sumerian Names, I: Ensuhkešdanna and Baba". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. American Schools of Oriental Research. 62: 29–43. doi:10.1086/JCS41103869. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 41103869. S2CID 164077908. Retrieved 2021-08-04.

- Sallaberger, Walther (2016), "Zababa", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-09-14

- Samet, Nili (2014). The lamentation over the destruction of Ur. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-292-1. OCLC 884593981.

- Selz, Gebhard (1995). Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt des altsumerischen Stadtstaates von Lagaš (in German). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum. ISBN 978-0-924171-00-0. OCLC 33334960.

- Sibbing-Plantholt, Irene (2022). The Image of Mesopotamian Divine Healers. Healing Goddesses and the Legitimization of Professional Asûs in the Mesopotamian Medical Marketplace. Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-51241-2. OCLC 1312171937.