_-_Sala_della_Lupa_-_Palazzo_dei_Conservatori_-_Musei_Capitolini_-_Rome_2016_-_Highlights_of_A._Manlius_Torquatus'_career.png.webp)

Aulus Manlius Torquatus Atticus (died before 216 BC) was a politician during the Roman Republic. Born into the prominent patrician family of the Manlii Torquati, he had a distinguished career, becoming censor in 247 BC, then twice consul in 244 and 241 BC, and possibly princeps senatus in 220 BC. Despite these prestigious magistracies, little is known about his life. He was a commander who served during the First Punic War, and might have pushed for the continuation of the war even after Carthage had sued for peace following the Roman victory at the Aegate Islands in 241 BC. The same year, he suppressed the revolt of the Faliscans in central Italy, for which he was awarded a triumph. At this occasion, he may have introduced the cult of Juno Curitis at Rome.

Family background

Atticus belonged to the patrician gens Manlia, one of the most important gentes of the Republic. Members of the family had held 9 consulships and 14 consular tribuneships before him.[2] Atticus' father and elder brother—both named Titus—are not known, but his grandfather—also named Titus—was consul in 299 and died during his magistracy.[3][4] Atticus was probably the uncle of his near-contemporary Titus Manlius Torquatus, like him twice consul in 235 and 224, censor in 231, and finally dictator in 208.[5]

The cognomen Torquatus was first received by Atticus' great-great-grandfather Titus Manlius Imperiosus in 361 after he had defeated a Gaul in single combat, and took his torque as a trophy.[6] The torque then became the emblem of the family, whose members proudly put it on the coins they minted. Imperiosus Torquatus was famous for his severity, by killing his own son after he had disobeyed him during a battle.[7][8]

The agnomen Atticus is a reference to Attica and shows that he was influenced by the growing Philhellenism at Rome. He may have reached a good competence in Greek and showed it in his name.[9] Several other prominent politicians adopted a Greek cognomen during the middle Republic, such as Quintus Publilius Philo or Quintus Marcius Philippus.[10] The same cognomen was used two centuries later by Cicero's friend Titus Pomponius Atticus after his long residency in Athens.[11]

Political career

Censorship (247 BC)

Atticus' first mention in history is his election as censor in 247, alongside Aulus Atilius Caiatinus, a plebeian with a distinguished career (twice consul in 258 and 254, dictator in 249). During the third century, the Manlii and the Atilii were the allies of the great patrician gens Fabia and members of these three gentes are often found together in the Fasti. Moreover, one of the consuls of 247 was Numerius Fabius Buteo. Friedrich Münzer furthermore suggested that Atticus was married to a Fabia.[12]

Atticus' accession to the censorship is exceptional because this magistracy was usually the pinnacle of a career at Rome, in theory reserved to former consuls (only six censors were in this situation between 312 and 31 BC).[13] This election can be explained by the influence of the Fabii, as well as the dearth of available former patrician consuls in the context of the First Punic War, as experienced commanders were needed on the field and several consuls had died in battle. Caiatinus was likely the most influential of the pair, as Atticus was a younger man. He is additionally recorded as the censor prior in the Fasti, which means the Centuriate Assembly elected him before Atticus.[12][14][15]

The censors completed the 38th lustrum and registered 241,212 Roman citizens, a sharp decline from the previous census (in 252), which numbered 297,797 citizens.[16] The defeats at Drepana and Lilybaeum combined with war attrition took a heavy toll on the Roman citizenry.[17] Finally, the censors drew the lectio—the list of senators—and named the princeps senatus. They might have chosen at this occasion Gnaeus Cornelius Blasio but it is also possible that he was appointed at the next lectio in 241.[18]

First consulship (244 BC)

Atticus was elected consul for the first time in 244 together with Gaius Sempronius Blaesus, a plebeian who had already been consul in 253.[19] Atticus is described by Cassiodorus—who relied on Livy for his list of consuls—as the consul prior.[20][21] Marcus Fabius Buteo was consul the previous year with another Atilius—Gaius Bulbus—and might have played a role in the election of Atticus and Blaesius.[22] Nothing is known on their activity as consuls; they possibly served in Sicily, where most of the operations of the First Punic War took place that year.[19] The two colonies of Brundisium and Fregenae were founded during their term.[23][24]

Second consulship (241 BC)

Atticus was elected consul a second time in 241, alongside the plebeian Quintus Lutatius Cerco.[25] The latter was the brother of Gaius Lutatius Catulus who won the Battle of the Aegate Islands at the end of his consulship, on 10 March 241 (magistrates took office on 1 May at that time).[26][27][28] Cassiodorus and Eutropius (who also relied on Livy) tell that Cerco was the consul prior and Atticus posterior, but in the Fasti Capitolini Atticus was moved to first place.[29][30][14] The Fasti were made under Augustus by the College of Pontiffs, whose members often moved their ancestors to first place in order to enhance the prestige of their family—a policy supported by Augustus who tried to revive several prominent patrician families—since being elected prior was the subject of great pride.[31] The Augustan pontiff Aulus Manlius Torquatus was thus responsible for the promotion of Atticus in the Fasti, as well as several other members of his family.[32][33]

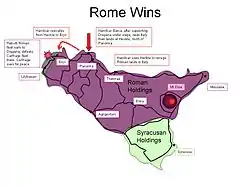

Zonaras tells that Catulus made a first treaty with Hamilcar after his victory, a few days before the end of his consulship, so he could be the one who ended the war. However, he and Polybius add that the "people of Rome" rejected the treaty, so his brother Cerco negotiated harsher terms upon Carthage after he entered office.[34][35] Adam Ziolkowski thinks that "the people" in fact showed its opposition by electing a consul who was against the treaty of Catulus; since Cerco could not have contradicted his brother, it means that the opposition came from Atticus, who wished to continue the war. Nevertheless, Atticus had to give way and accept making peace, but obtained additional clauses in the new treaty.[36][37][38] This compromise might still have been considered too lenient towards Carthage by a faction in the senate, hence why Rome took Sardinia a few years later.[39] Incidentally, Sardinia was conquered by Atticus' nephew Titus Manlius Torquatus in 235.

Cerco's and Atticus' consulship was marked by natural disasters in Rome, which according to Orosius "almost destroyed the City".[40] He adds that the Tiber river overflowed and crushed all the buildings located in the plain. This flood was particularly devastating because at this time most buildings were made in wood and clay, which are vulnerable to water.[41] A major fire also ravaged the Temple of Vesta and most of the area around the Forum. The Pontifex Maximus—Lucius Caecilius Metellus—almost died while trying to save the palladium from the burning temple.[23] Ancient authors tell that the Faliscans—an Italic people living in Southern Etruria—revolted in order to take advantage of the situation.[42][43][44] The real cause is more probably the expiration of a 50-year treaty concluded in 293.[45] E. S. Staveley even considers that this war was part of a deliberate strategy from Rome to tighten its control of Etruria. He notes that the censors of 241 built the Via Aurelia which went northwards from Rome to Pisa and founded colonies in the area.[46]

According to Zonaras, Atticus had some difficulties overcoming the Faliscans in his first battle against them, as they defeated his infantry; the cavalry nonetheless saved the situation. He had a better result in the second battle, which ended the campaign after only six days. The consuls seized the Faliscans' horses, slaves, arms, half of their territory and displaced their capital of Falerii to a defenceless location at Falerii Novii. Zonaras' account describes Atticus as sole commander, but Cerco and Atticus were both awarded a triumph for the victory, respectively celebrated on 1 and 4 March 240.[44][47][48][49] The two consuls are also named together on a Faliscan bronze breastplate with an inscription saying "captured at Falerii" (as booty).[50][51] The patron-goddess of Falerii was Iuno Curritis, whom Atticus brought to Rome by founding a temple dedicated to her on the Campus Martius (its exact location is still unknown), while Cerco founded the Temple of Fortuna Publica on the Quirinal Hill.[52] Both consuls were likely fulfilling a vow to these goddesses that they had made on the battlefield.[53]

Several ancient authors tell that Atticus' nephew—Titus Torquatus—closed the gate of the Temple of Janus, after his victorious campaign in Sardinia during his consulship of 235. This act symbolically meant that Rome and its neighbours were at peace. It was only the first time that the temple was closed since the reign of Numa Pompilius—the legendary second king of Rome—and remained so for eight years; its gates then stayed open until Augustus closed them again after the Battle of Actium in 31 BC.[54][55][56] However, as Livy says that this event took place "after the First Punic War", Tim Cornell and Staveley place it in 241, when Atticus was consul as it makes more sense to close the Temple of Janus at the end of a 23-year war than for a small campaign in Sardinia.[57] The consensus nonetheless remains in favour of 235.[58][59][60][61]

Princeps Senatus (220–216 BC)

Atticus disappears from ancient sources after his second consulship. However, since Atticus was elected censor at a younger age than usual, he probably outlived the other former censors. Therefore, he may have been named princeps senatus during the lectio of 220, because before 208, the censors automatically appointed as such the former censor with the most seniority. The princeps senatus was the first senator to speak in the debates and was thus very influential in the Senate. The suggestion that Atticus was princeps was made by Francis Ryan on the assumption that Atticus was still alive in 220; he adds that he must have died before 216, when Marcus Fabius Buteo became princeps senatus.[63][64]

Pliny tells that a former consul named Aulus Torquatus died while eating a cake.[65] It could be Atticus, but Münzer favours the consul of 164, also named Aulus Torquatus.[66]

Stemma of the Manlii Torquati

Stemma taken from Münzer until "A. Manlius Torquatus, d. 208" and then Mitchell, with corrections. All dates are BC.[67][68]

|

Dictator |

|

Censor |

|

Consul | ||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Imperiosus Torquatus dict. 353, 349, 320 cos. 347, 344, 340 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Torquatus d. 340 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Torquatus cos. 299 | L. Manlius Torquatus legate 295 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Torquatus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Torquatus | A. Manlius Torquatus Atticus cens. 247; cos. 244, 241 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Torquatus cos. 235, 224 cens. 231; dict. 208 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A. Manlius Torquatus d. 208 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Torquatus cos. 165 | A. Manlius Torquatus cos. 164 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Torquatus pr. 137 | D. Junius Silanus Manlianus pr. 141, d. 140 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Torquatus | L. Manlius Torquatus qu. circa 113 | A. Manlius Torquatus | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T. Manlius Torquatus pr. 69 | P. Cornelius Lentulus Spinther (adopted) augur 57 | Manlia | L. Manlius Torquatus cos. 65 | A. Manlius Torquatus pr. 70 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L. Manlius Torquatus pr. 49 | A. Manlius Torquatus qu. 43, pontifex | A. Manlius Torquatus | T. Manlius Torquatus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, p. 308.

- ↑ Degrassi, Fasti Capitolini, pp. 28–57.

- ↑ Broughton, vol. I, pp. 173, 174 (note 2).

- ↑ A plastron bearing an inscription dated 241 gives a different filiation for Atticus, described as the "son of Gaius". It is probably a mistake as the praenomen Gaius was never used by the Manlii. Cf. Flower, "Inscribed breastplate", pp. 225–230.

- ↑ Münzer, RE, vol. 27, p. 1207.

- ↑ Livy, vii. 10.

- ↑ Livy, viii. 7, 8.

- ↑ Broughton, vol. I, pp. 136, 137.

- ↑ Gruen, Culture and National Identity, p. 230.

- ↑ Oakley, Commentary on Livy IX, p. 424.

- ↑ Cicero, De Finibus, v. 2.

- 1 2 Münzer, Roman Aristocratic Parties, pp. 59, 60, 402 (note 61).

- ↑ Ryan, Rank and Participation, p. 142.

- 1 2 Degrassi, Fasti Capitolini, pp. 56, 57.

- ↑ Suolahti, Roman Censors, pp. 550, 551.

- ↑ Livy, Periochae, 18, 19.

- ↑ Scullard, Cambridge Ancient History, vol. 7, part 2, pp. 563–564. There is a typo in the book, as Scullard meant the census of 247, not 237 (there was no census that year).

- ↑ Ryan, Rank and Participation, pp. 219–221, 223.

- 1 2 Broughton, vol. I, p. 217.

- ↑ Cassiodorus, Chronica, L. 310 Archived 2019-08-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Taylor & Broughton, "The Order of the Two Consuls' Names", p. 6.

- ↑ Suolahti, Roman Censors, p. 283.

- 1 2 Livy, Periochae, 19.

- ↑ Velleius, i. 14.

- ↑ Broughton, vol. I, p. 219.

- ↑ Eutropius, ii. 27.

- ↑ Broughton, vol. I, p. 218.

- ↑ Pina Polo, Consul at Rome, pp. 13–20, who however notes the uncertainty on the consuls' exact dates before 217 BC.

- ↑ Eutropius, ii. 28.

- ↑ Cassiodorus, Chronica, L. 313 Archived 2019-08-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Taylor & Broughton, "Order of the Consuls' Names", p. 166.

- ↑ Taylor, "Augustan Editing", pp. 76, 79 (note 13).

- ↑ Mitchell, "The Torquati", p. 27.

- ↑ Polybius, i. 63.

- ↑ Zonaras, viii. 17.

- ↑ Ziolkowski, Temples of mid-Republican Rome, pp. 41–45.

- ↑ Wardle "Valerius Maximus", pp. 382–384, who follows Ziolkowski on this point.

- ↑ Miano, Fortuna, p. 25 (note 25). Miano rejects Ziolkowski's theory on the ground that there are not enough sources to support it.

- ↑ Bleckmann, Die römische Nobilität, p. 223.

- ↑ Orosius, iv. 11.

- ↑ Aldrete, Floods of the Tiber, pp. 111, 112.

- ↑ Polybius, i. 65.

- ↑ Livy, Periochae, 20.

- 1 2 Zonaras, viii. 18.

- ↑ Walbank, Commentary on Polybius, vol. I, p. 131.

- ↑ Staveley, Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2, p. 431.

- ↑ Degrassi, Fasti Capitolini, p. 101.

- ↑ Keay et al., "Falerii Novi", pp. 1, 2.

- ↑ Konrad, "Lutatius and the 'Sortes Praenestinae'", p. 168.

- ↑ Zimmerman, "La fin de Falerii Veteres", p. 41.

- ↑ Flower, "Inscribed breastplate", pp. 225, 230, 232. The full inscription reads:

Q. LVTATIO C. F. A. MANLIO C. F.

CONSOLIBVS FALERIES CAPTO.

- ↑ Ziolkowski, Temples of mid-Republican Rome, pp. 40–45, 62–67.

- ↑ Leach, "Fortune's Extremities", p. 112.

- ↑ Livy, i. 9.

- ↑ Plutarch, Numa, 20.

- ↑ Orosius, iv.12 § 2.

- ↑ Tim Cornell, E. Staveley, Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part II, pp. 383, 453 (note 62).

- ↑ Broughton, vol. I, p. 223.

- ↑ Hoyos, Unplanned Wars, p. 130 (note 25).

- ↑ Brennan, The Praetorship, p. 90.

- ↑ Jonathan Prag, "Sicily and Sardinia-Corsica: the first provinces", in Hoyos (ed.), Roman Imperialism, p. 59.

- ↑ Mattingly et al., The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. I, p. 177.

- ↑ Ryan, Rank and Participation, pp. 209, 210, 217–219.

- ↑ Beck, Karriere und Hierarchie, p. 281 (note 66). Beck supports Ryan's theory.

- ↑ Pliny, vii. 183.

- ↑ Münzer, RE, vol. 27, p. 1212.

- ↑ Mitchell, "The Torquati".

- ↑ Münzer, RE, vol. 27, pp. 1181-1182.

Bibliography

Ancient works

- Cassiodorus, Chronica (Latin text in the Monumenta Germaniae Historica).

- Cicero, De Finibus (Latin text on Wikisource).

- Eutropius, Brevarium (English translation by Rev. John Selby Watson on Wikisource).

- Fasti Capitolini, Fasti Triumphales.

- Livy, Ab Urbe Condita (English translation by Rev. Canon Roberts on Wikisource), Periochae (English translation by Jona Lendering on Livius.org).

- Orosius, Historiae Adversus Paganos ("Histories against the Pagans") (Latin text on Attalus.org).

- Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis (English translation by Harris Rackham, W.H.S. Jones, and D.E. Eichholz on Wikisource).

- Plutarch, Parallel lives (English translation of the Life of Numa by John Dryden and Arthur Hugh Clough on Wikisource).

- Polybius, The Histories (English translation by William Roger Paton on LacusCurtius).

- Valerius Maximus, Factorum ac Dictorum Memorabilium (English translation by Samuel Speed on EEBO).

- Marcus Velleius Paterculus, Compendium (English translation by Rev. John Selby Watson on Wikisource).

- Joannes Zonaras, Epitome (English translation of Cassius Dio and Zonaras by Earnest Cary on LacusCurtius).

Modern works

- Gregory S. Aldrete, Floods of the Tiber in Ancient Rome, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Hans Beck, Karriere und Hierarchie: Die römische Aristokratie und die Anfänge des cursus honorum in der mittleren Republik, Berlin, Akademie Verlag, 2005.

- Bruno Bleckmann, Die römische Nobilität im Ersten Punischen Krieg, Berlin, Akademie Verlag, 2002.

- T. Corey Brennan, The Praetorship in the Roman Republic, Oxford University Press, 2000.

- T. Robert S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, American Philological Association, 1951–1952.

- Michael Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, Cambridge University Press, 1974–2001.

- Attilio Degrassi, Fasti Capitolini recensuit, praefatus est, indicibus instruxit Atilius Degrassi, Turin, 1954.

- Harriet Flower, "The significance of an inscribed breastplate captured at Falerii in 241 B.C.", Journal of Roman Archaeology, Volume 11 (1998), pp. 224–232.

- Erich S. Gruen, Culture and National Identity in Republican Rome, Ithaca & New York, Cornell University Press, 1992.

- Dexter Hoyos, Unplanned Wars: The Origins of the First and Second Punic Wars, Berlin & New York, Walter de Gruyter, 1998.

- —— (editor), A Companion to Roman Imperialism, Leiden/Boston, Brill, 2013.

- Simon Keay et al., "Falerii Novi: A New Survey of the Walled Area", Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 68 (2000), pp. 1–93.

- C. F. Konrad, "Lutatius and the 'Sortes Praenestinae'", Hermes, 143. Jahrg., H. 2 (2015), pp. 153–171.

- Eleanor W. Leach, "Fortune's Extremities: Q. Lutatius Catulus and Largo Argentina Temple B: A Roman Consular and his Monument", Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 55 (2010), pp. 111–134.

- Harold Mattingly, Edward A. Sydenham, Carol H. V. Sutherland, The Roman Imperial Coinage, vol. I, from 31 BC to AD 69, London, Spink & Son, 1923–1984.

- Daniele Miano, Fortuna: Deity and Concept in Archaic and Republican Italy, Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Jane F. Mitchell, "The Torquati", in Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, vol. 15, part 1, (January 1966), pp. 23–31.

- Friedrich Münzer, Roman Aristocratic Parties and Families, translated by Thérèse Ridley, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999 (originally published in 1920).

- Stephen P. Oakley, A Commentary on Livy: Volume III, Book IX, Oxford University Press, 2005.

- August Pauly, Georg Wissowa, Friedrich Münzer, et alii, Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft (abbreviated RE), J. B. Metzler, Stuttgart, 1894–1980.

- Francisco Pina Polo, The Consul at Rome: The Civil Functions of the Consuls in the Roman Republic, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Francis X. Ryan, Rank and Participation in the Republican Senate, Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1998.

- Jaakko Suolahti, The Roman Censors, a study on social structure, Helsinki, Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1963.

- Lily Ross Taylor and T. Robert S. Broughton, "The Order of the Two Consuls' Names in the Yearly Lists", Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 19 (1949), pp. 3–14.

- ——, "New Indications of Augustan Editing in the Capitoline Fasti", Classical Philology, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Apr., 1951), pp. 73–80.

- —— and T. Robert S. Broughton, "The Order of the Consuls' Names in Official Republican Lists", Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, vol. 17, part 2 (Apr., 1968), pp. 166–172.

- Frank William Walbank, A. E. Astin, M. W. Frederiksen, R. M. Ogilvie (editors), The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. VII, part 2, The Rise of Rome to 220 B.C., Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- ——, A Commentary on Polybius, Oxford University Press, 1979.

- David Wardle, "Valerius Maximus and the End of the First Punic War", Latomus, T. 64, Fasc. 2 (2005), pp. 377–384.

- Jean-Louis Zimmermann, "La fin de Falerii Veteres: Un témoignage archéologique", The J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, Vol. 14 (1986), pp. 37–42.

- Adam Ziolkowski, The Temples of Mid-Republican Rome and their Historical and Topographical Context, Rome, 1992.