Antonio di Paolo Benivieni | |

|---|---|

Antonio di Paolo Benivieni (1443‐1502) | |

| Born | November 3, 1443 |

| Died | 1502 Florence, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | autopsy, pathology |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | medicine |

Antonio di Paolo Benivieni (1443–1502) was a Florentine physician who pioneered the use of the autopsy and many medical historians have considered him a founder of pathology.[1][2]

Biography

Early life and education

Benivieni was born in Florence, Italy, on November 3, 1443. His father Paolo was a nobleman, notary and a member, alongside his wife Nastagia de’ Bruni, of a prominent and wealthy Florentine family from S. Giovanni. Their coat of arms had a silver moon with a blue background. He was the first of five children alongside Domenico, theology reader at the University of Pisa, and Girolamo, famous poet and scholar. At first he embraced the literary career and was a pupil of Francesco da Castiglione during his studies of Greek. Subsequently, he abandoned this path to devote himself "ad philosophie ... et medicine secreta perscrutandum", continuing however to cultivate letters having the protection of the House of Medici: Cosimo il Vecchio and Piero il Gottoso. Benivieni's early education was provided by tutors and he then studied medicine at the university of Pisa and Siena.[3]

Adult life and career

The beginning of his activity as a doctor can be dated to around 1470, since Girolamo, in the epistle to Giovanni Rosati, writes that his brother went "medicating for about thirty-two years". In Florence Benivieni soon acquired a great reputation for safety in diagnoses, for the wise use of drugs and above all for his skill as a surgeon. Due to a lack of data, it is not possible to establish the year in which Benivieni was enrolled in the “Arte dei medici e degli speziali”.[4]

In 1473 he was appointed consul of the Arte and from March 1494 to May 1496 he was prior. He treated members of noble and powerful families such as the Medici, the Pazzi, the Adimari, the Strozzi family, and was also a doctor of convents (San Nicolò, S. Caterina, SS. Annunziata, S. Marco). He treated Francesco of 16 years old of the Guicciardini family, and he was a friend and follower of Gerolamo Savonarola as well as his doctor. He had a particular friendship with Lorenzo il Magnifico and he treated his daughter. In 1464 he dedicated to Lorenzo il Magnifico the “εγκώμιον Cosmi”, then the “De regimine sanitatis” and again the “De peste”.[5]

In the book of Memories, which is an autobiographical manuscript in the State Archives of Florence, there is various information on Benivieni's economic life; he noted in this book private business, purchases, payments and sometimes even notes on his profession. Most of his income came from possessions in Florence and in the countryside. Antonio Benivieni owned various Greek, Latin and Arab works, including many medical works such as "I Consilia" of Taddeo and treatises on poisons, baths and various medications. This collection shows not only Antonio Benivieni's great medical culture but also the humanistic one.[4]

Death

Benivieni died on November 2, 1502, in Florence and was buried in the chapel of the Basilica of SS. Annunziata. On the tombstone was engraved “D.O.M. Antonio Benivenio patri philosopho ac doctor sibi posterisque Michael Benivenius posuit. Obiit die II. November an. sal. MDII ". The chapel then passed to the Donati family and in 1665 Carlo Donati changed the plaque which is still visible today.[4]

Contributions to medicine

Cultural context

During the Renaissance (14th - 17th century),a new curiosity aroused towards pathological conditions of the human body. Attempts in this direction had already been made by the Alexandrian school, but the first autopsy done for this purpose was performed in 1302 in Bologna. However, it was only at the end of the fifteenth century, after the Church and governments granted the authorisation for the free exercise of anatomical dissection, that the autopsy, aimed at knowing the cause of death, became a common practice both in hospitals and in private houses.[6]

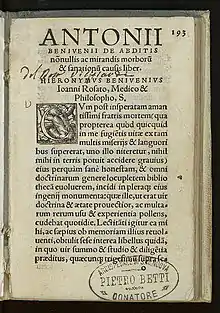

De Abditis Morborum Causis

He was considered a skilled diagnostician and praised for his ability to treat difficult cases. The observations reported in the work "Abditis morborum causis" (Florence 1507) are the first objective anatomical-pathological studies; in this work emerges the intuition that it is necessary to seek the existence of relations between the clinic, pathology, and pathological anatomy for the correct understanding of morbid phenomena. It will be this same intuition that after two centuries will inspire Giovanni Battista Morgagni in the compilation of the work that marks the beginning of pathological anatomy “De sedibus et causis morborum per anatomen indagatis" (1761).[6][5]

In the work of Benivieni are reported some of the most important pathological anatomy representations, such as the discovery of gallbladder stones, a peritoneal abscess, a stomach and intestine cancer, an intestinal perforation (the first described in the history of medicine), and a megacolon; he was the first to objectively study teratology, and also in the clinical field he had a very important contribution with his studies on helminthology and on the transmission of syphilis from the mother to the fetus.[5][7]

History of the work

Antonio Benivieni did not publish his works when he was alive, after his death his brother Girolamo, while reorganizing his belongings, found some writings that he described as very interesting clinical cases; then he sent them to Giovanni Rosati, an important physician, who suggested publishing them because of their brilliance so they published a part of those writings calling them “Antonii Benivenii, De abditis nonnullis ac mirandis morborum et sanationum causis, Florentiae” (1507).[3]

The title would appear to have been suggested by Celsus's " Abdditae morborum causae", in these writings the observations of Benivieni imply that he knew about medicine, surgery and obstetrics. The work was subsequently published again in Latin and in the nineteenth century we have the first Italian translation by Carlo Burci, which was based on the sixteenth-century edition because the original manuscript at that time was lost; it was later found by Burci himself, who discovered that the original manuscript contained a dedication.[8]

This dedication was to Lorenzo Lorenzani and stated that the plan of his work was to divide his observations into three groups of one hundred; this dedication and some unpublished observations were subsequently published by Francesco Puccinotti and Burci in the treatise “Storia della Medicina". Nowadays the original manuscript is lost and no trace remains.[8]

Benivieni's findings

Some of the protocols which resemble the ones used nowadays in autopsy are described in De Abditis Morborum Causis ("The Hidden Causes of Disease ), which is now considered one of the first works in the science of pathology. This is one of the reasons why he has been referred to as the "father of pathologic anatomy.” [2]

The observations, which are about 111, are mainly clinical and yet stand out for Beninvieni's skills in medicine, surgery and obstetrics. The following are particularly noteworthy: on Gallic disease (n. 1), important for the year of compilation; on liver stones in a woman (No. III); on the bone resection he performed on a young girl (n. XXV); on a dead fetus which he extracted with the hook (n. XXIX); on the vascular connections (n. LXVIII); on lithotripsy (n. LXXX); the various teratological observations are also important.[3][5]

Furthermore, other interesting pathological observations to point out are: the presence of an abscess between the laminae of the mesentery in a young woman who suffered from violent pains in the abdomen; narrowing of the intestine with enlargement and hardening of its walls (possibly a cancer) in a woman subject to colic and constipation; a cancer of a pylorus, described as scirrhous and constricted in a man prone to chronic vomiting. Benivieni also saw intestinal perforations in chronic dysentery (it recalls the amoebic dysentery); a megacolon in a child who died of colic; a bristly, hairy-looking heart in an executed man.[3][8]

The importance of Benivieni's work

The great importance of Benivieni's work, for which he obtained the appellant of "father of pathological anatomy", consists in the association of observations carried out during clinical cases and necropsy. He was looking for the causes of death and he endeavoured to establish a parallelism between the symptoms reported in life and anatomical lesions. The anatomical-clinical method started by Benivieni, will slowly develop in the following centuries and culminates with Giovanni Battista Morgagni. His work is also a valuable testimony of the importance already attributed to the autopsy at the time.[8]

Notes

- ↑ Hajdu SI (2010). "A note from history". 116: 2493–2498.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Fye WB (1996). "Antonio di Paolo Benivieni". Clinical Cardiology. 19 (8): 678–679. doi:10.1002/clc.4960190820. PMID 8864346. S2CID 221578437.

- 1 2 3 4 "Enciclopedia Treccani, Antonio Benivieni".

- 1 2 3 "Enciclopedia Treccani, Antonio Benivieni".

- 1 2 3 4 Enciclopedia Italiana Fondata da Giovanni Treccani. Vol. VI. 1930.

- 1 2 Borghi, Luca (29 January 2022). Sense of Humors: The Human Factor in the History of Medicine.

- ↑ L'Enciclopedia. Torino: La Biblioteca di Repubblica. 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 W.F.Bynum, Helen Bynum, ed. (2007). Dictionary of Medical Biography. Vol. 1 A-B. p. 188.

Bibliography

• Hajdu SI (2010). "A note from history". Cancer. United States. 116 (10): 2493–2498. doi:10.1002/cncr.25000. ISSN 1097-0142. PMID 20225228.

• Fye WB (1996). "Antonio di Paolo Benivieni". Clinical Cardiology. 19 (8): 678–679. doi:10.1002/clc.4960190820. ISSN 1932-8737. PMID 8864346.

• "Enciclopedia Treccani, Antonio Benivieni".

• Borghi, Luca (29 January 2022). Sense of Humors: The Human Factor in the History of Medicine. Independently published. ISBN 979-8401116277.

• Enciclopedia Italiana [Balta/Bik] (in Italian). Vol. VI. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana fondata da Giovanni Treccani. 1930.

• W.F.Bynum, Helen Bynum, ed. (2007). Dictionary of Medical Biography. Vol. 1 A-B. Westport, Connecticut-London: Greenwood Press. p. 188.

•L'Enciclopedia [opera realizzata dalle Redazioni Grandi Opere di Cultura UTET] (in Italian). Torino: La Biblioteca di Repubblica. 2003.