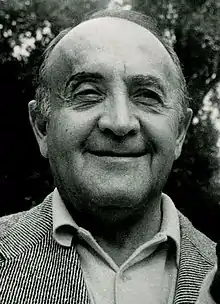

Andrew Peter Solt (June 7, 1916 – November 4, 1990) was a Hungarian-born Hollywood screenwriter for film and television. Born as Endre Peter Strausz, he began his career as a playwright in Budapest. Solt is best known for writing the screenplay for In a Lonely Place (1950), a critically acclaimed film noir directed by Nicholas Ray and starring Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame. The film is on the Time magazine "All-Time 100 Movies" list of greatest films since 1923.[1] In 2007, it was selected for preservation by the National Film Registry[2] of the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Solt also co-wrote the screenplay for Joan of Arc (1948), collaborating with Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Maxwell Anderson. Adapted from Anderson's hit Broadway show Joan of Lorraine (1946), the production starred Ingrid Bergman and was nominated for seven Oscars and won two.[3]

Early life

Solt was born in Budapest, Austria-Hungary just before the end of World War I (Hungary became an independent nation in 1918). His parents were Jewish and owned one of the city's top hotels, the Bristol. The adjacent Bristol Café was a popular meeting spot for Budapest's literary and artistic community.[4] Growing up amidst Budapest's thriving musical, theatrical and cabaret culture, Solt started writing plays when in his teens. Five musicals were successfully staged by the time he was 21.[5]

Solt's journey to Hollywood and a career as screenwriter was propelled by a fortuitous chance encounter with Cardinal George Mundelein, the influential Archbishop of Chicago, known in the United States for his outspoken support of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. In 1938, Mundelein came to Budapest to attend the 34th International Eucharistic Congress, a gathering of Catholic Church prelates hundreds of thousands of others from around the world. Mundelein happened to be staying at the Bristol and met Solt who was working at the family hotel's reception desk. Solt told the Cardinal that if he wanted to see Budapest he could accompany him on a drive around the city. He so impressed Mundelein during the auto tour that the Cardinal offered to sponsor him if he ever wanted to come to the United States.

Career: Broadway to Hollywood

Solt soon took him up on his offer, and in 1939 was on a ship to New York City. It didn't take long for him to get caught up in the city's vibrant theater scene. One of his plays had been a smash hit throughout Europe in 1938. Translated into English as Accidents Don't Happen, it was attracting keen interest from a number of Broadway producers. The play wound up being optioned by famed songwriter Irving Berlin and Buddy DeSylva, the stage and screen producer. DeSylva wanted to do Accidents as a musical with Berlin, but the plans fell through.[6] However, in 1944 the Shubert Organization bought the play, opening it on Broadway as a musical comedy in 1945.[7]

By then Solt was already a screenwriter in Hollywood, having gone there at the suggestion of Berlin who told him the motion picture studios were always on the lookout for new writers and new properties like his plays. Solt arrived on the West Coast in 1940. He started as a $250-a-week contract writer for Columbia Pictures, then quickly earned his first credit for a movie adaptation of another of his plays, The Orchestra Bride. The film version, They All Kissed the Bride, was released in 1942, and starred Joan Crawford and Melvyn Douglas in the screwball comedy.

Solt, universally known to friends and colleagues by his nickname Bundy, went on to write a string of screenplays and adaptations for major films from the 1940s through the 1950s.[8] They included Without Reservations (1946) starring John Wayne and Claudette Colbert; The Jolson Story (1946) with Larry Parks; Joan of Arc (1946); a remake of the 1933 classic Little Women (1949) with the four March sisters played by Elizabeth Taylor, June Allyson, Margaret O'Brien and Janet Leigh; Whirlpool (1949), a film noir with Gene Tierney and Richard Conte, co-written with Ben Hecht; In a Lonely Place (1950); mystery Thunder on the Hill (1951) with Claudette Colbert and Ann Blyth; and a Mario Lanza musical set in Capri, For the First Time (1959); it turned out to be the popular singer's final movie (he died two months after it opened).

Over that span, Solt worked on films guided by some of Hollywood's leading directors including Victor Fleming, Mervyn LeRoy, Otto Preminger, Rudolph Maté, Douglas Sirk, William Dieterle, Tay Garnett and Nicholas Ray.

Fleming—best known for helming two of the most popular movies in cinema history, The Wizard of Oz and Gone With The Wind, both released in 1939—directed Joan of Arc.[9] Fleming not only had Solt and Anderson's ambitious screenplay and Bergman's star power to work with, but also a budget of $5 million, an enormous sum in those days, provided by veteran independent producer Walter Wanger, who had a reputation as a socially conscious movie executive who produced provocative message movies and glittering romantic melodramas.[10]

Joan of Arc got a lukewarm reception from moviegoers—its box office slightly exceeded its budget—and critics gave it mixed reviews. Wrote New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther: "Pictorially, it is one of the most magnificent films ever made, bespeaking the vast sum of money and the effort expended on it. Dramatically, it has moments of tremendous excitement and shock. And emotionally it has glimmers of the deep poignancy of the Maid. But, somehow, the huge combination of pageantry, legend and pathos—of spectacle, color, court intrigues and the historic ordeal of a girl—while honestly intended, fails to come fully to life or to give a profound comprehension of the torment and triumph of Joan."[11]

The film, however, did get recognized by Academy Awards voters. At the 1949 ceremonies, Joan of Arc won two Oscars—for best color photography and best costume design in a color film—out of a total of seven nominations. Bergman was nominated for best actress and co-star José Ferrer got the nod in the best supporting actor category. Other nominations were for best film editing, best art direction and set decoration, and best music. The film's producer, Walter Wanger, meanwhile received an honorary Academy Award for "distinguished service to the industry in adding to its moral stature in the world community by his production of the picture Joan of Arc."[12] Wanger, who had received an honorary Oscar in 1946 for his service as president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (1939-1945) declined to accept the honor in 1949 out of pique that Joan of Arc, which he considered one of his best movies, had not received a nomination for best picture of the year.[13]

In a Lonely Place

Solt's most acclaimed screenplay is the one he wrote for In a Lonely Place. In the film, Bogart, in one of his darkest roles, plays Dixon Steele, a gifted but paranoid screenwriter with a mean temper, especially when he gets boozed up. He gets into a rage that may or may not have led to a murder. He meets and falls in love with Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame), a fledgling actress, and a romantic relationship ensues. But when another woman Steele has frequently been seen with is found murdered, he comes under suspicion.

Well-received when it first opened in 1950, critics in their appraisals since then have placed it in the top rank of film noir classics and singled it out as one of director Ray's best films. At its premiere in 1950, Crowther in his New York Times review praised Solt's script for being "almost as flinty as Bogart himself", noting that "because Mr. Solt did not compromise to fabricate a happy ending, the climax packs both surprise and a punch."[14] He also commented on its sardonic depiction of Hollywood, noting the movie "lets go with a few sharp barbs at the dynasty system in movieland." When Time's chief film critic Richard Schickel updated the magazine's all-time 100-best movies list and added In a Lonely Place, he said he "loved every minute of this sardonic portrayal of life on Hollywood's fringes (the characters surrounding Steele are etched in acid)."[15]

"Part of the enduring fascination of In A Lonely Place is how Ray and screenwriter Andrew Solt make it work on so many seemingly contradictory levels", a reviewer wrote when a Blu-ray-DVD version was put out in 2016 by Criterion, known for its curated catalog of film classics.[16] "It's a great and achingly romantic love story that also, no less than Hitchcock's Vertigo, lays bare the possessiveness, the willful blindness, and the derangement of romantic obsession." And The Wall Street Journal review of the 2016 DVD re-release stated: "There is no noir more profoundly sad than Nicholas Ray's In a Lonely Place, which unfolds with dark lyricism against a backdrop of violence, cynicism, and suspicion. One of Ray's most indelible stories involving characters who lash out in pointless fury—and one of his most personal films—it incorporates melodrama, echoes of Shakespeare, and heart-stopping performances by Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame."[17]

Television and theater

In the 1950s Solt took up writing scripts for television, mostly for the weekly anthology series that were popular at the time. He wrote a number of teleplays for Alfred Hitchcock Presents (still seen in reruns), and also for General Electric Theater, Schlitz Playhouse of Stars and Ford Theatre.

Even after he had turned to screenwriting full-time, Solt continued to be involved in the theater. In 1945, a tour was launched for his play A Gift for the Bride.[18] It starred Luise Rainer, who had the unique distinction of being the only person to win the Best Actress Oscar two years in a row, for The Great Ziegfeld (1937) and The Good Earth (1938). In 1946 Judy O'Connor, a play he wrote with Hollywood producer Frank Ross, opened in Boston[19] and starred Don DeFore, but never made it to Broadway. (Solt and Ross worked on a number of projects together. Solt did an early treatment of The Robe (1953), a tale of the Christ in Roman times, which became one of Ross's biggest hits, and is still remembered as the first movie released in widescreen CinemaScope.)

One of his most tantalizing endeavors involved Somerset Maugham, the world-famous British novelist and short-story writer. Solt's acquaintance Lady Mendl (Elsie de Wolfe), the international socialite and renowned decorator, convinced her friend Maugham that the young Hungarian writer would be the perfect person to turn his first novel, Liza of Lambeth, into a play.[20] Maugham, who had resisted such proposals in the past, approved Solt's version, and the play was scheduled to open on Broadway in 1949. But this project never came to fruition.

Personal

When Solt arrived in Hollywood, he fit right in with the town's roster of actors, directors, and writers who were either born in Hungary or of Hungarian descent—among them George Cukor, Michael Curtiz, Leslie Howard, Zoltan Korda, and Andre de Toth.

Probably the Hungarian entertainment personality most familiar to the American public was Zsa Zsa Gabor, the movie actress (Moulin Rouge, Touch of Evil) who was perhaps best known for her glamorous lifestyle, multiple marriages and frequent appearances on television talk shows. Solt knew her, having grown up in Budapest with her and her sisters Magda and Eva (who also went on to an acting career). The matriarch of the family, Jolie Gabor, had opened a jewelry boutique in the lobby of the Bristol.[21][22] Solt renewed his friendship with the Gabors when the family arrived in Hollywood in 1942. He remained a lifelong friend of Zsa Zsa, and frequently accompanied her to movie premieres and to parties at well-known Hollywood haunts like Ciro's, Chasen's and Romanoff's where he was also often seen dining with other celebrity friends like Joan Crawford, James Mason, Ginger Rogers and Kathryn Grayson.[23][24] Solt and Gabor's careers also overlapped at times. Gabor appeared in two movies on which Solt was a writer: Lovely to Look At and For the First Time. Solt is said to have had a hand in getting her a co-starring role in the Lanza film. There was also an ill-fated venture. Solt wrote a script for a Western that was to star Gabor and Dominican playboy Porfirio Rubirosa, with whom she was having an affair at the time.[25] The film, tentatively titled A Western Affair and later Rubi Rides Again was in pre-production when the Immigration and Naturalization Service ruled that Rubirosa was not eligible to work on the movie.[26] He appealed but lost and the movie never got made.

During the Red Scare era of the early 1950s when blacklisting and naming names infected Hollywood and ruined careers, Solt found himself entangled in a strange case of mistaken identity. In a tabloid magazine article about him, Solt was misidentified in a photo caption as "a well-known Communist." He was confused with then-blacklisted screenwriter Waldo Salt because of their similar last names.[27] He was even receiving mail for the writer. (Salt, who refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, had acknowledged he had been a member of the American Communist Party from 1939 to 1955.) Solt successfully sued for a retraction to avoid ever again being labeled a Communist. In fact he was a staunch anti-Communist and had sued the Soviet-dominated government of Hungary to regain his family' s hotel in Budapest which had been illegally seized.

Solt's life and screenwriting career are documented in the University at Albany, SUNY's German and Jewish Intellectual Émigré Collections.[28] Included in the archive is a collection of Solt's personal papers along with a taped interview with his brother George Solt (now deceased) in which he reminisces about the family history and the details of his sibling's entertainment career.

Solt's nephew is Andrew W. Solt, producer, writer and director of movies and television documentaries; and John Solt, a poet and writer specializing in Japanese and Asian studies—he is the author of Shredding the Tapestry of Meaning: The Poetry and Poetics of Kitasono Katue.[29]

Works

Movies

- 1942: They All Kissed the Bride (adaptation - as Andrew P. Solt) / (story - as Andrew P. Solt)

- 1943: My Kingdom for a Cook (screenplay) / (story)

- 1946: Without Reservations (screenplay)

- 1946: The Jolson Story (adaptation)

- 1948: Joan of Arc (screenplay)

- 1949: Little Women (screenplay)

- 1949: Whirlpool (screenplay)

- 1950: In a Lonely Place (screenplay)

- 1950: September Affair (screenplay - uncredited)

- 1951: Thunder on the Hill

- 1951: The Family Secret

- 1952: Lovely to Look At (additional dialogue)

- 1952: One Minute to Zero (uncredited)

- 1954: The Lusty Men (uncredited)

- 1954: King High (writer)

- 1958: … und nichts als die Wahrheit (writer)

- 1959: For the First Time (writer)

- 1959: Ángel del infierno (writer)

- 1961: Murder After Death (written by)

Television

- 1954: Rheingold Theatre

- 1954: General Electric Theater

- 1954: The Ford Television Theatre

- 1954: Lux Video Theatre

- 1957: French Provincial

- 1957: Schlitz Playhouse

- 1956: Safe Conduct

- 1956: The Legacy

- 1958: The Return of the Hero

- 1956–1958: Alfred Hitchcock Presents

- 1961: Miami Undercover

References

- ↑ "All-Time 100 Movies". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ↑ "National Film Registry 2007". Library of Congress Information Bulletin. January–February 2008. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ↑ Joan of Arc, retrieved January 2, 2019

- ↑ Bishop, Ted (June 6, 2017). Ink: Culture, Wonder, and Our Relationship with the Written Word. Penguin. ISBN 9780735234956.

- ↑ Details of Solt's early years in Budapest from an archive of Solt's personal papers at SUNY Albany--including recollections of his early life and career.

- ↑ "Hedda Hopper column". Los Angeles Times. October 15, 1944.

- ↑ "Shuberts Tuning Up Old Hungarian Play". Daily News. October 13, 1944.

- ↑ "Andrew Solt". IMDb. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ↑ Sragow, Michael (December 6, 2013). Victor Fleming: An American Movie Master. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813144429.

- ↑ Bernstein, Matthew (1994). Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9781452904689.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (November 12, 1948). "Ingrid Bergman Plays Title Role in 'Joan of Arc' at Victoria -Two Other Films Arrive". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ↑ "Joan of Arc". IMDb. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ↑ "Movie Review 1948 Joan of Arc Starring Ingrid Bergman". Maid of Heaven. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (May 18, 1950). "The Screen: Three Films Make Their Bows; Humphrey Bogart Movie, 'In a Lonely Place,' at Paramount --Import at Trans-Lux 'Annie Get Your Gun,' Starring Betty Hutton, Is Presented at Loew's State Theatre". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard. "All-Time 100 Movies". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- ↑ "The Curbside Criterion: In a Lonely Place". Hammer to Nail. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ↑ "Noir From a Poet Of Love and Violence". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 11, 1945.

- ↑ The Boston Globe, March 27, 1946.

- ↑ "Louella Parsons column". Hearst Newspapers. December 15, 1948.

- ↑ Porter, Darwin (2013). Those Glamorous Gabors: Bombshells from Budapest. Blood Moon Productions, Limited. ISBN 9781936003358.

- ↑ Frank, Gerold (1960). Zsa Zsa Gabor: My Story Written for Me by Gerold Frank. World Publishing Company.

- ↑ Harrison, Carroll (December 2, 1951). Los Angeles Herald Examiner.

- ↑ "Louella Parsons column". San Francisco Examiner. January 30, 1952.

- ↑ United Press International, July 26, 1954.

- ↑ United Press International, July 27, 1954.

- ↑ "Louella Parsons column". Hearst Newspapers. April 18, 1953.

- ↑ "German and Jewish Intellectual Émigré". University Libraries University at Albany. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ↑ Solt, John (1999). Shredding the Tapestry of Meaning: The Poetry and Poetics of Kitasono Katue (1902-1978). Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 9780674060746.