| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Ammonium oxalate | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

Ammonium ethanedioate | |

| Other names

Diammonium oxalate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.012.912 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| [NH4]2C2O4 | |

| Molar mass | 124.096 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Colorless or white crystalline solid |

| Density | 1.5 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 70 C (158 F, 343.15 K) |

| 5.20 g/(100 ml) (25 °C)[1] | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| H302, H312, H319 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

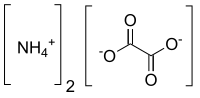

Ammonium oxalate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula [NH4]2C2O4. Its formula is often written as (NH4)2C2O4 or (COONH4)2. It is an ammonium salt of oxalic acid. It consists of ammonium cations ([NH4]+) and oxalate anions (C2O2−4). The structure of ammonium oxalate is ([NH4]+)2[C2O4]2−. Ammonium oxalate sometimes comes as a monohydrate ([NH4]2C2O4·H2O). It is a colorless or white salt under standard conditions and is odorless and non-volatile. It occurs in many plants and vegetables.

Vertebrate

It is produced in the body of vertebrates by metabolism of glyoxylic acid or ascorbic acid. It is not metabolized but excreted in the urine.[2] It is a constituent of some types of kidney stone.[3][4] It is also found in guano.

Mineralogy

Oxammite is a natural mineral form of ammonium oxalate. This mineral is extremely rare. It is an organic mineral derived from guano.[5]

Chemistry

Ammonium oxalate is used as an analytical reagent and general reducing agent.[2] It and other oxalates are used as anticoagulants, to preserve blood outside the body.

Earth sciences

Acid ammonium oxalate (ammonium oxalate acidified to pH 3 with oxalic acid) is commonly employed in soil chemical analysis to extract iron and aluminium from poorly-crystalline minerals (such as ferrihydrite), iron(II)-bearing minerals (such as magnetite) and organic matter.[6]

References

- 1 2 John Rumble (June 18, 2018). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (99th ed.). CRC Press. pp. 4–41. ISBN 978-1138561632.

- 1 2 National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Database; CID 14213 (accessed 15 November 2016).

- ↑ The International Pharmacopoeia, p.1292, Volume 1, World Health Organization, 2006 ISBN 92-4-156301-X.

- ↑ N G Coley, "The collateral sciences in the work of Golding Bird (1814-1854)", Medical History, iss.4, vol.13, October 1969, pp.372.

- ↑ "Home". mindat.org.

- ↑ Rayment, George; Lyons, David (2011). Soil Chemical Methods - Australasia. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9780643101364.