An alternate care site (ACS) is a medical treatment facility established in a non-traditional setting during a public-health crisis (or other event causing strain on local medical resources) as a means of providing additional capacity to deliver medical care within a given area.[1][2]: 1 The term encompasses both civilian-operated medical facilities established in non-traditional places such as hotels, gymnasiums, and convention centers, or other "structure[s] of opportunity," as well as military field medical units being used for public-health purposes.[2]: 2 [3][4][5] Usually, the option of establishing an ACS becomes relevant once the scale of an emergency extends beyond a single metropolitan area.[6]: 4 Though commonly established (or, at a minimum, overseen) by public-health authorities, ACSes can also be established by private entities, such as large employers.[7]: 7 ACSes have been widely used as part of the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and in other recent crises such as the Western African Ebola virus epidemic.[4][8]

History

Likely the first use of non-traditional facilities to provide large-scale medical care took place during the Coalition Wars towards the end of the eighteenth century.[9]: 1393 French surgeon-major Dominique Jean Larrey sought to improve on contemporary practice whereby wounded soldiers remained on the battlefield until they could be evacuated to distant centralized medical facilities.[9]: 1393–94 Under Larrey, medical care was brought to the wounded soldiers (rather than vice versa) for the first time during a battle at Metz in 1793.[9]: 1395

An early civilian use of ACSes occurred during the Spanish flu pandemic, which began in 1918. For example, in Philadelphia, an abandoned building owned by the University of Pennsylvania was converted to this use.[10]: 138 Similarly, ACSes were set up in unused school buildings and hotels to treat influenza patients throughout Canada.[11]: 128–29 The experience with the Spanish flu pandemic highlighted the importance of planning for ACS setup before a crisis strikes: while buildings were easy to find, equipment and staff were in short supply, complicating the establishment of functioning ACSes.[11]: 129

In the decades following the Spanish flu pandemic, the primary response to hospital overcrowding arising from a disaster was to activate "surge capacity" within a hospital, rather than establishing other care facilities such as an ACS.[12]: 253 More recently, ACSes have been established in response to large-scale disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina, when the Dallas Convention Center was used for this purpose for its first time.[12]: 253–54 Following the 2010 Haiti earthquake, an ACS operated there for several months.[13]

Characteristics

Layout

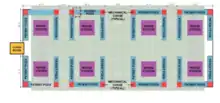

Because an ACS might be established in a variety of different building types, different models exist for the layout of ACSes. There are two basic layout types, which are based on the type of building in which the ACS is established: an open layout for buildings with large open spaces (e.g., convention center or arena) and a non-open layout for buildings with numerous rooms (e.g., hotel or dormitory).[14]: 2 To be effective, the layout of an ACS must include analogues of several features of traditional healthcare facilities, including patient rooms, triage area(s), staff rest area(s), storage space, and the like.[3] The conversion of space within an existing medical facility from non-clinical use to clinical use does not qualify as the creation of an ACS because the building itself is already used for purposes of medical care.[8]

Services

In addition to physical space, an ACS requires the other elements necessary for a medical facility; these include medical staff and equipment, as well as relationships with the broader healthcare system in the area.[2]: 2 An ACS might provide a variety of medical care based on the available resources and needs of the local community. Generally, as the level of care provided by an ACS increases, the number of patients it is able to serve decreases (and vice versa).[7]: 6–7 ACSes are commonly characterized as adhering to one of the following three models:[2]: 2 [3][4]

- Non-acute care—The type of care that would not ordinarily require hospitalization, or would only require low levels of hospital care, such as minimal supportive oxygen therapy or light assistance with activities of daily living

- Hybrid care—The type of care for which patients would ordinarily be hospitalized, but for which intensive care is not required

- Acute care—The type of care for which patients would require an intensive care unit, such as use of a ventilator[2]: 2 [3]

Regardless of the care model, each ACS needs to be staffed by the requisite medical professionals. There are a variety of models for retaining the necessary staffing. One model (which the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recommends as the easiest way for local governments in the United States to be reimbursed for the care provided at an ACS) is for a public-health authority to contract with a local hospital to run the ACS as if it were part of the hospital.[15]: 1

In addition to the provision of medical care to its patients, an ACS of any level must be able to provide ancillary services, including food service, proper disposal of medical and non-medical waste, and laundry facilities.[3] Accordingly, a well-staffed ACS generally includes personnel from a variety of non-medical disciplines, including supply chain, administration, and other support roles.[6]: 3

An ACS that is no longer actively providing care, but remains outfitted to resume doing so on short notice is said to be in warm status.[2]: 27 [16]

COVID-19 pandemic

Uses

In March 2020, as public-health authorities began to recognize the potential scope of the COVID-19 pandemic, an initial question was whether to use ACSes for those patients with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, or without it.[4] While the intuitive answer initially appeared to be that ACSes should be for virus-free patients, several factors ultimately led to a consensus forming around using these facilities exclusively for patients with the virus; these factors included the unreliability of testing, the ability to conserve personal protective equipment and the ability for the facility to specialize in the care of COVID-19.[4] Commingling patients with and without the virus could lead to additional complications regarding infection control.[3][4] Initial studies found that ACSes were particularly valuable for treating those with less-severe illnesses, to allow traditional hospitals to focus on the care of patients requiring the full scope of care available in those facilities.[4][14]: 1

COVID-19 ACSes

While many facilities were considered as potential ACS locations during the COVID-19 pandemic, the following are notable for having been operationalized and taken on significant numbers of patients:

- ExCeL London in England[4]

- Javits Center in New York City[5]

- Boston Convention and Exhibition Center[17]

- Baltimore Convention Center in Baltimore, Maryland[18]

References

- ↑ U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. "Alternate Care Sites (ACS)". Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Federal Healthcare Resilience Taskforce (June 30, 2020). "Alternate Care Site Toolkit" (PDF) (3rd ed.).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (April 23, 2020). "Considerations for Alternate Care Sites".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Meyer, Gregg S.; Blanchfield, Bonnie B.; Bohmer, Richard M.J.; Mountford, James; Vanderwagen, W. Craig (May 22, 2020). "Alternative Care Sites for the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Early U.S. and U.K. Experience". NEJM Catalyst. doi:10.1056/CAT.20.0224 (inactive August 1, 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - 1 2 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (April 1, 2020). "Army Corps, Partners Establish Alternate Care Facility at Javits Center; First Patients Arrive". Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- 1 2 Deloitte (2020). "Establishing an Alternate Care Site (ACS)" (PDF). Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- 1 2 Institute of Medicine (2012). Handling, Dan; Altevogt, Bruce M.; Viswanathan, Kristin; Gostin, Lawrence O. (eds.). Crisis Standards of Care: A Systems Framework for Catastrophic Disaster Response (PDF). Vol. 5: Alternate Care Systems. Washington: The National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-25347-5.

- 1 2 American Society for Health Care Engineering (November 6, 2020). "Converting alternate care sites to patient space options".

- 1 2 3 Skandalakis, Panagiotis N.; Lainas, Panagiotis; Zoras, Odyseas; Skandalakis, John E.; Mirilas, Petros (2006). "To Afford the Wounded Speedy Assistance: Dominique Jean Larrey and Napoleon". World Journal of Surgery. Zurich. 30 (8): 1392–99. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0436-8. PMID 16850154. S2CID 42597837.

- ↑ Starr, Isaac (2006). "Influenza in 1918: Recollections of the Epidemic in Philadelphia". Annals of Internal Medicine. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians. 145 (2): 138–140. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-2-200607180-00132. PMID 16801626. S2CID 41861480.

- 1 2 McGinnis, Janice P. Dickin (1977). "The Impact of Epidemic Influenza: Canada, 1918–1919" (PDF). Historical Papers. Fredericton: Canadian Historical Association. 12: 120–140. doi:10.7202/030824ar. ISSN 1712-9109. PMID 11614608. S2CID 9268818.

- 1 2 Eastman, Alexander L.; Rinnert, Kathy J.; Nemeth, Ira R.; Fowler, Raymond L.; Minei, Joseph P. (2007). "Alternate Site Surge Capacity in Times of Public Health Disaster Maintains Trauma Center and Emergency Department Integrity: Hurricane Katrina". The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 63 (2): 253–57. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3180d0a70e. PMID 17693820.

- ↑ U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (February 16, 2011). "Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Post-Earthquake Injuries Treated at a Field Hospital—Haiti, 2010". JAMA. 305 (7): 664–66.

- 1 2 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (March 22, 2020). "Alternate Care Sites (ACS) Implementation Support Materials" (PDF).

- ↑ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (May 26, 2020). "CMS Programs & Payment for Care in Hospital Alternate Care Sites" (PDF).

- ↑ Federal Emergency Management Agency (May 12, 2020). "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: Alternate Care Site (ACS) "Warm Sites"".

- ↑ Levin, Jake (June 2, 2020). "Last 2 Coronavirus Patients at Boston Hope Field Hospital Released to Cheers". NBC 10 Boston. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. "Baltimore Convention Center Field Hospital: One State's Experience during COVID-19" (PDF). Retrieved December 10, 2020.